PDF Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filipino Immigrants in Canada: a Literature Review and Directions for Further Research on Second-Tier Cities and Rural Areas

Filipino Immigrants in Canada: A Literature Review and Directions for Further Research on Second-Tier Cities and Rural Areas Tom Lusis [email protected] Department of Geography Introduction This study provides an overview of the literature on Filipino immigrants in the Canadian context1. The central argument of the paper is that this body of literature has three distinct characteristics, an urban bias, a focus on the economic integration of immigrants, and a gender bias. Cutting across these topics are two central themes which are the importance of social networks in immigration experiences, and the frequency of transnational ties between communities in Canada and the Philippines. I suggest that an examination of these trends and themes not only exposes the gaps in the literature but also shows how the Filipino-Canadian community is well positioned for a study of immigrants in secondary cities and rural areas. The text is structured as follows. The first section examines the three main trends in the literature. The second section reviews the two themes that are reoccurring throughout the studies on Filipino immigrants. Section three will point out the gaps in the literature and provide directions for further research. Finally, the fourth section presents the concluding arguments. Trends in the Literature The urban bias In recent years the literature on Filipino-Canadians has tended to focus on two cities, Toronto and Vancouver. Of the eighteen sources reviewed for this paper, 50 per cent used data gathered from the Filipino community in these cities. If further comparisons are made, Toronto has received the most attention. For 1 This study examines the literature where Filipino immigrants were the main topic of investigation. -

Voices Rising

Voices Rising Xiaoping Li Voices Rising: Asian Canadian Cultural Activism © UBC Press 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), www.accesscopyright.ca. 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Canada on ancient-forest-free paper (100% post-consumer recycled) that is processed chlorine- and acid-free, with vegetable-based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Li, Xiaoping, 1954- Voices rising: Asian Canadian cultural activism / Xiaoping Li. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7748-1221-4 1. Asian Canadians – Ethnic identity. 2. Asian Canadians – Social life and customs. 3. Asian Canadians – Politics and government. 4. Social participation – Canada. 5. Asian Canadians – Biography. I. Title. FC106.A75L4 2007 971.00495 C2006-907057-1 UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP), and of the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social -

Ecologies Everywhere the Green Smell of Cis-3-Hexanal

TCR THE CAPILANO REVIEW ecologies Everywhere the green smell of cis-3-hexanal. —Sonnet L’Abbé Editor Brook Houglum Web Editor Jenny Penberthy Managing Editor Tamara Lee The Capilano Press Colin Browne, Pierre Coupey, Roger Farr, Crystal Hurdle, Andrew Klobucar, Aurelea Society Board Mahood, Jenny Penberthy, Elizabeth Rains, Bob Sherrin, George Stanley, Sharon Thesen Contributing Art Editor Keith Wallace Contributing Editors Clint Burnham, Erín Moure, Lisa Robertson Founding Editor Pierre Coupey Designer Jan Westendorp Website Design Adam Jones Interns Iain Angus, Alexander McMillan, Teeanna Munro, Thomas Weideman The Capilano Review is published by The Capilano Press Society. Canadian subscription rates for one year are $25 hst included for individuals. Institutional rates are $35 plus hst. Outside Canada, add $5 and pay in U.S. funds. Address correspondence to The Capilano Review, 2055 Purcell Way, North Vancouver, BC v7j 3h5. Subscribe online at www. thecapilanoreview.ca For our submission guidelines, please see our website or mail us an sase. Submissions must include an sase with Canadian postage stamps, international reply coupons, or funds for return postage or they will not be considered—do not use U.S. postage on the sase. The Capilano Review does not take responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, nor do we consider simultaneous submissions or previously published work; e-mail submissions are not considered. Copyright remains the property of the author or artist. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the author or artist. Please contact accesscopyright.ca for permissions. The Capilano Review gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the British Columbia Arts Council, Capilano University, and the Canada Council for the Arts. -

Early South Asian Immigration to Canada: the Story of the Sikhs

1 EARLY SOUTH ASIAN IMMIGRATION TO CANADA: THE STORY OF THE SIKHS The first South Asians to arrive in Canada were Indian men of the Sikh faith. From their earliest visit in 1897 until Canada’s racially-based immigration policies were relaxed in 1951, most of Canada’s South Asian immigrants were Sikhs from the Punjab region of India. Their story is essential to understanding the history of South Asian Canadians. 1897-1904: In 1897, India was part of the British dominion, and Sikhs in particular were well known for their service as soldiers for the empire. The very first Indians to visit Canada were part of a Sikh military contingent traveling through British Columbia on the way to Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations that year in London. A second group of Sikh soldiers visited in 1902 on the way to Edward VII’s coronation. They made an appearance before a crowd in Vancouver, prompting wild applause. The enthusiastic reception was documented with a headline in Vancouver’s Daily Province which read, “Turbaned Men Excite Interest: Awe-inspiring men from India held the crowds”. Sikhs were esteemed for their military service, and Canadians were impressed by their stately and exotic appearance. The group passed through Montreal before sailing to London, and when they returned to India, they brought tales of Canada back with them. 1904 – 1913 ANTI-ASIAN SENTIMENT In 1904, 45 men from India immigrated to Canada. Indian immigrants were few and far between until 1906 and 1907 when a brief surge brought 4700-5000 of them to the country, most settling in B.C. -

“Too Asian?”: Racism, Privilege and Post- Secondary Education

Alberta Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 59, No. 4, Winter 2013, 698-702 Book Review “Too Asian?”: Racism, Privilege and Post- Secondary Education R. J. Gilmour, Davina Bhandar, Jeet Heer, and Michael C. K. Ma, editors Toronto: Between the Lines, 2012 Reviewed by: Yvette Munro York University This book, an anthology of essays by university faculty, graduate students, cultural critics, and human rights activists, examines issues of race and exclusion in Canadian postsecondary education. It responds to the highly controversial and inflammatory “Too Asian?” article published in Maclean’s magazine in November 2010. The article begins with interviews with two white female students from an elite Toronto private secondary school about their university application choices. The interviewees disclose preferences for selecting universities with fewer Asian students based on their assumptions that these universities may be more socially rewarding and less academically competitive. The Maclean’s article constructs a profile of Asian students as socially rigid, unassimilated, obsessed with academic performance, and under intense parental pressure. The composite emerges in comparison with their Canadian counterparts, assumed to be white, non-immigrant, middle-class, upwardly socially mobile and fun-loving. While the article acknowledges Asian students’ experiences of discrimination, it reinforces predominantly the problematic stereotypes of socially disengaged Asian students who perform well in academics despite perceived poor English skills. According to the article, Asian students socialize only with other Asians. By raising the question about whether or not Canadian university campuses have become too Asian, Maclean’s posits that the once admirable Canadian meritocratic approach to admissions, intended to be fair and neutral, may be allowing for an unintended racialization of the university campus. -

Body Histories and the Limits of Life in Asian Canadian Literature

Body Histories and the Limits of Life in Asian Canadian Literature by Ranbir Kaur Banwait M.A., Simon Fraser University, 2008 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Ranbir Kaur Banwait 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2014 Approval Name: Ranbir Kaur Banwait Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (English) Title of Thesis: Body Histories and the Limits of Life in Asian Canadian Literature Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Sean Zwagerman Associate Professor of English Dr. Christine Kim Co-Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor of English Dr. David Chariandy Co-Senior Supervisor Associate Professor of English Dr. Larissa Lai Associate Professor of English University of Calgary Dr. Lara Campbell Internal Examiner Associate Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Dr. Donald Goellnicht External Examiner Professor of English and Cultural Studies McMaster University Date Defended/Approved: July 24, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract Histories of racialization in Canada are closely tied to the development of eugenics and racial hygiene movements, but also to broader concerns, expressed throughout Western modernity, regarding the “health” of nation states and their subjects. This dissertation analyses books by Velma Demerson, Hiromi Goto, David Chariandy, Rita Wong, Roy Miki and Larissa Lai to argue that Asian Canadian literature reveals, in heightened critical terms, how the politics of racial difference has -

Lai CV April 24 2018 Ucalg For

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Curriculum Vitae Date: April 2018 1. SURNAME: Lai FIRST NAME: Larissa MIDDLE NAME(S): -- 2. DEPARTMENT/SCHOOL: English 3. FACULTY: Arts 4. PRESENT RANK: Associate Professor/ CRC II SINCE: 2014 5. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates University of Calgary PhD English 2001 - 2006 University of East Anglia MA Creative Writing 2000 - 2001 University of British Columbia BA (Hon.) Sociology 1985 - 1990 Title of Dissertation and Name of Supervisor Dissertation: The “I” of the Storm: Practice, Subjectivity and Time Zones in Asian Canadian Writing Supervisor: Dr. Aruna Srivastava 6. EMPLOYMENT RECORD (a) University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates University of Calgary, Department of English Associate Professor/ CRC 2014-present II in Creative Writing University of British Columbia, Department of English Associate Professor 2014-2016 (on leave) University of British Columbia, Department of English Assistant Professor 2007-2014 University of British Columbia, Department of English SSHRC Postdoctoral 2006-2007 Fellow Simon Fraser University, Department of English Writer-in-Residence 2006 University of Calgary, Department of English Instructor 2005 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Instructor 2004 Clarion West, Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop Instructor 2004 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Teaching Assistant 2002-2004 University of Calgary, Department of English Teaching Assistant 2001-2002 Writers for Change, Asian Canadian Writers’ -

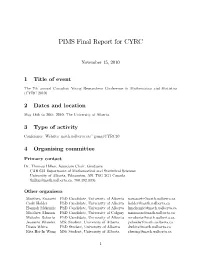

PIMS Final Report for CYRC

PIMS Final Report for CYRC November 15, 2010 1 Title of event The 7th annual Canadian Young Researchers Conference in Mathematics and Statistics (CYRC 2010) 2 Dates and location May 18th to 20th, 2010, The University of Alberta 3 Type of activity Conference. Website: math.ualberta.ca/~game/CYRC10 4 Organising committee Primary contact Dr. Thomas Hillen, Associate Chair, Graduate CAB 632 Department of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB. T6G 2G1 Canada [email protected], 780.492.3395 Other organisers Matthew Emmett PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Cody Holder PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Hannah Mckenzie PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Matthew Musson PhD Candidate, University of Calgary [email protected] Malcolm Roberts PhD Candidate, University of Alberta [email protected] Jeanette Wheeler MSc Student, University of Alberta [email protected] Diana White PhD Student, University of Alberta [email protected] Rita Hei-In Wong MSc Student, University of Alberta [email protected] 1 5 Conference Summary The Canadian Young Researchers Conference in Mathematics and Statistics (CYRC) is an annual event that provides a unique forum for young mathematicians across Canada to present their research and to collaborate with their peers. All young academics involved in mathematics research were invited to give a scientific talk describing their work and to attend talks on a host of current research topics in mathematics and statistics. Participants had the opportunity to build and strengthen lasting personal and professional relationships, to develop and improve their communication skills, and gained valuable experience in the environment of a scientific conference. -

Autumn 2018 Vol. 32

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS FRANK ZAPPA A complete guide to his more than BC 100 recorded works. BOOKWORLD PAGE 25 VOL. 32 • NO. 3 • Autumn 2018 A darkly comedic memoir by Lindsay Wong NOT CRAZY RICH ASIANS See page 7 Avoid Screens FICTION: ILLUSTRATION: POLITICS: W.D. Valgardson’s Julie Flett reflects Christy Clark’s gothic crime on creating art for downfall is a PHOTO novel. picture books. political thriller. PAGE 28 PAGE 35 PAGE 10 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40010086 SHIMON IMPROVING YOUR SEX LIFE WITH MINDFULNESS 15 9781459813335 9781459812871 “A magical encounter 9781459818194 “Plenty of with nature” 9781459819924 “Engaging and encouragement here.” —Kirkus Reviews An intimate look at the 9781459816503 triumphant.” —Booklist work of a world-renowned “Vibrant and engaging.” —CM Magazine artist and naturalist. —Kirkus Reviews Wade in the water and traipse through the trees. 9781459812734 9781459813458 9781459818019 “Eye-catching.” 9781459815131 “A calm, peaceful tone.” 9781459815865 “Entertaining.” —Kirkus Reviews “As magical as the —Kirkus Reviews “Concise and still —CM Magazine ocean itself.” thorough.” —Angie Abdou —Kirkus Reviews Find these and other great BC books at your local independent bookstore. 2 BC BOOKWORLD AUTUMN 2018 PEOPLE TOPSELLERS* Cyndi Suarez BCThe Power Manual: How to Master Complex Power Dynamics (New Society $19.99) Sophie Bienvenu translated by Rhonda Mullins Around Her (Talonbooks $19.95) Collin Varner The Flora and Fauna of Coastal British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Heritage House $39.95) Sarah Cox Breaching the Peace: The Site C Dam and a Valley’s Stand against Big Hydro (UBC Press $24.95) Jen Currin PHOTO Hider/Seeker “It’s poetry’s uncanniness (Anvil Press $20) that attracts me.” SAWCHUK LORNA CROZIER LAURA “I come, after all, from a family of very ordinary, hard-working Richard Wagamese Saskatchewan people.” Richard Wagamese Indian Horse (D&M $21.95) NE OF THE FIRST PUBLIC EVENTS FOR ing the rent. -

Combating Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia in Canada: Toward Pandemic Anti-Racism Education in Post-Covid-19

Beijing International Review of Education 3 (2021) 187-211 Combating Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia in Canada: Toward Pandemic Anti-Racism Education in Post-covid-19 Shibao GUO | ORCID: 0000-0001-6551-5468 Professor, Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada [email protected] Yan GUO | ORCID: 0000-0001-8666-6169 Professor, Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada [email protected] Abstract Canada is often held up internationally as a successful model of immigration. Yet, Canada’s history, since its birth as a nation one hundred and fifty-four years ago, is one of contested racial and ethnic relations. Its racial and ethnic conflict and division resurfaces during covid-19 when there has been a surge in racism and xenophobia across the country towards Asian Canadians, particularly those of Chinese descent. Drawing on critical race theory and critical discourse analysis, this article critically analyzes incidents that were reported in popular press during the pandemic pertaining to this topic. The analysis shows how deeply rooted racial discrimination is in Canada. It also reveals that the anti-Asian and anti-Chinese racism and xenophobia reflects and retains the historical process of discursive racialization by which Asian Canadians have been socially constructed as biologically inferior, culturally backward, and racially undesirable. To combat and eliminate racism, we propose a framework of pandemic anti-racism education for the purpose of achieving educational improvement in post-covid-19. Keywords covid-19 – racism – xenophobia – anti-racism education – Canada © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2021 | doi:10.1163/25902539-03020004Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 12:19:12PM via free access 188 guo and guo Since the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of the novel coro- navirus (covid-19) a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, almost every country on the globe has been affected by the spread of the virus. -

When Might the Two Cultural Worlds of Second Generation Biculturals Collide?

WHEN MIGHT THE TWO CULTURAL WORLDS OF SECOND GENERATION BICULTURALS COLLIDE? ABSTRACT Second generation youth often identify with two cultures (heritage and Canadian). Although these biculturals usually negotiate their lives between two cultural worlds with ease, there are situations where conflicts may arise because of an incompatibility between the norms associated with each culture. Our research has identified some key points where bicultural conflicts can occur for second generation Canadians. econd generation youth in Canada are the children of parents who immigrated to Canada from another country. Although there is a tremendous amount of diversity among individuals Swithin this second generation, they often share the feature of being bicultural. Culture can be defined by the norms and standards of a group that will delineate the appropriateness of behaviour. Bicultural individuals, therefore, have psychological access to two sets of cultural norms that may be tied to geography, ethnicity and/or religion. In the case of second generation Canadians, our research culture, social identity and intergroup relations. that pertain to multicultural societies, namely, His University. at research York focuses on issues Richard N. Lalonde is a professor of Psychology RICHARD N. LALONDE focuses on their heritage culture and their Canadian culture. Heritage norms are typically acquired from parents, extended family and the ethnic community to which parents belong. The basis of “Canadian” norms is much broader because they are acquired through the infrastructure of Canadian society (e.g., schools, media, social services), the neighbourhoods in which they live and from many of their peers. Moreover, Canadian norms are acquired through either a majority English-language or a majority French-language context, while heritage norms may be acquired through a completely different language. -

South Asian and Chinese Canadians Account for 29% of Grocery Spend in Toronto and Vancouver

WAVE2 SOUTH ASIAN AND CHINESE CANADIANS ACCOUNT FOR 29% OF GROCERY SPEND IN TORONTO AND VANCOUVER TORONTO (May 20, 2008)—Two of the fastest-growing Canadian population segments are also above average in their grocery spending and now account for nearly 1-in-3 dollars spent on groceries in Toronto and Vancouver according to a new study by Solutions Research Group (SRG), a Toronto-based market research firm. The estimated total size of the grocery category in Toronto and Vancouver is $17 billion dollars annually. The 2006 Census enumerated nearly 2.5 million (2,479,500) individuals who identified themselves as South Asian or Chinese, representing a growth rate of 27% over 2001. This rate of growth wasfive times faster than the 5.4% increase for the Canadian population as a whole in the same period. Chinese Canadian shoppers reported spending $136 on groceries weekly on average, 9% higher than the benchmark for all residents of Toronto and Vancouver. Top destinations for Chinese Canadians for groceries in Toronto were No Frills (mentioned first by 26%) followed closely by T&T Supermarket (23%), with Loblaws third at 8%. In Vancouver, T&T Supermarket accounted for a remarkable 53%, with Real Canadian Superstore second at 17%. South Asian Canadians spend even more on groceries, indexing 23% higher than an average household in Toronto and Vancouver. No Frills is the leading banner in Toronto among South Asians (42%), followed by Food Basics and Wal-Mart. In Vancouver, Real Canadian Superstore (27%) is the top destination, followed by Save-on-Foods and Wal-Mart.