MELTING POT Casting a Caribbean Chinese Body by JOSHUA LUE CHEE KONG 刘贵強

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sauces Reconsidered

SAUCES RECONSIDERED Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy General Editor: Ken Albala, Professor of History, University of the Pacific ([email protected]) Rowman & Littlefield Executive Editor: Suzanne Staszak-Silva ([email protected]) Food studies is a vibrant and thriving field encompassing not only cooking and eating habits but also issues such as health, sustainability, food safety, and animal rights. Scholars in disciplines as diverse as history, anthropol- ogy, sociology, literature, and the arts focus on food. The mission of Row- man & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy is to publish the best in food scholarship, harnessing the energy, ideas, and creativity of a wide array of food writers today. This broad line of food-related titles will range from food history, interdisciplinary food studies monographs, general inter- est series, and popular trade titles to textbooks for students and budding chefs, scholarly cookbooks, and reference works. Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam: Food and Drink in the Long Nine- teenth Century, by Erica J. Peters Three World Cuisines: Italian, Mexican, Chinese, by Ken Albala Food and Social Media: You Are What You Tweet, by Signe Rousseau Food and the Novel in Nineteenth-Century America, by Mark McWilliams Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America, by Bruce Kraig and Patty Carroll A Year in Food and Beer: Recipes and Beer Pairings for Every Season, by Emily Baime and Darin Michaels Celebraciones Mexicanas: History, Traditions, and Recipes, by Andrea Law- son Gray and Adriana Almazán Lahl The Food Section: Newspaper Women and the Culinary Community, by Kimberly Wilmot Voss Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits, and the Return of Artisanal Foods, by Suzanne Cope Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Years of World Culinary History, Cul- ture, and Social Influence, by Janet Clarkson Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy: From Kitchen to Table, by Kath- erine A. -

Newsletter Winter 2016 Issue

新 西 籣 東 增 會 館 THE TUNG JUNG ASSOCIATION OF NZ INC PO Box 9058, Wellington, New Zealand www.tungjung.org.nz Newsletter Winter 2016 issue ______ —— The Tung Jung Association of New Zealand Committee 2015—2016 President Gordon Wu 388 3560 Membership Kaye Wong 388 8060 Vice President Peter Wong 388 5828 Alex Chang 499 8032 Secretaries- English Valerie Ting 565 4421 Property Joe Chang 388 9135 Chinese Kevin Zeng 021 669628 Willie Wong 386 3099 Treasurer Robert Ting 478 6253 Newsletter Gordon Wu 388 3560 Assistant treasurer Virginia Ng 232 9971 Peter Moon 389 8819 Social Peter Wong 388 5828 Website Gordon Wu 388 3560 Elaine Chang 388 9135 Peter Moon 389 8819 Andrina Chang 499 8032 Valerie Ting 565 4421 Public Gordon Wu 388 3560 Peter Moon 389 8819 relations Please visit our website at http://www.tungjung.org.nz 1 President’s report……….. The past three months we have had extremely good weather and a lot of things have been happening which has made time go by very quickly. By the time you receive this newsletter, winter will have arrived and you will have time to read it! Since the last newsletter, the Association was invited to attend the launch of a rewrite of a book written by an Australi- an author on Chinese ANZAC’s. He had omitted that there were also New Zealand ANZAC’s, so it was rewritten to include the New Zealand soldiers during World War One. Robert Ting attended on behalf of the Association. A day excursion to the Wairarapa was made in early March. -

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

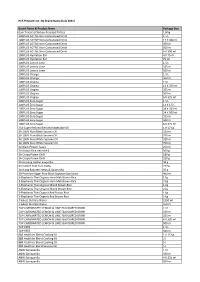

HCS Website List As of 30 June 2021 Working File.Xlsx

HCS Product List - By Brand Name (July 2021) Brand Name & Product Name Package Size (Lim Traders) Chicken Breaded Patties 1.8 kg 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 1.5 L 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 12 X 300 ml 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 300 ml 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 500 ml 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 6 X 300 ml 100PLUS Hydration Bar 4 X 75 ml 100PLUS Hydration Bar 75 ml 100PLUS Lemon Lime 1.5 L 100PLUS Lemon Lime 325 ml 100PLUS Lemon Lime 500 ml 100PLUS Orange 1.5 L 100PLUS Orange 500 ml 100PLUS Original 1.5 L 100PLUS Original 12 X 325 ml 100PLUS Original 325 ml 100PLUS Original 500 ml 100PLUS Original 6 X 325 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 1.5 L 100PLUS Zero Sugar 12 X 1.5 L 100PLUS Zero Sugar 24 X 325 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 24 X 500 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 325 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 500 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 6 X 325 ml 333 Super Refined Blended Vegetable Oil 1 X 17 kg 3A 100% Pure Black Sesame Oil 320 ml 3A 100% Pure Black Sesame Oil 750 ml 3A 100% Pure White Sesame Oil 320 ml 3A 100% Pure White Sesame Oil 750 ml 3A Black Pepper Sauce 250 ml 3A Brown Rice Vermicelli 500 g 3A Crispy Prawn Chilli 180 g 3A Crispy Prawn Chilli 320 g 3A Ginseng Herbal Soup Mix 40 g 3A Instant Tom Yum Paste 227 g 3A Klang Bakuteh Herbs & Spices Mix 35 g 3A Premium Sugar Free Black Soybean Soy Sauce 400 ml 3-Elephants Thai Organic Hom Mali Brown Rice 1 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Hom Mali Brown Rice 2 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Mixed Brown Rice 1 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Mixed Brown Rice 2 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Red Brown -

Meat 4 - 7 Fresh, Frozen, Prepared and Manufactured Meat

PURVEYORS OF THE FINEST YACHT PROVISIONS Suppliers to superyachts globally since 2003 Product Directory ...total provisioning solutions worldwide Contents Meat 4 - 7 Fresh, frozen, prepared and manufactured meat. Superyacht Supplies deliver excellence,whether you Our experience in international logistics within the food Special meats – from Antelope to Wagyu are on the French or Italian Riviera, Sardinia, Corsica, and drinks industry enables us to deliver efficiently and The Netherlands, Germany, Spain & Balearics, economically to other destinations using airfreight out Fish and Seafood 8 - 9 Montenegro, Malta, Greece & Greek Islands, Turkey, of London, the world’s largest cargo hub, with more Fresh, frozen, prepared, smoked and manufactured Egypt, Oman, Dubai, Maldives, Seychelles, Thailand, direct flights and competitively priced routes, important fish and seafood. India, Andaman Islands, Antigua, St Maarten and factors when shipping perishables. Caribbean Islands and beyond*. Fruit and Vegetables 10 - 12 In turn we work closely with established and Fresh, frozen, prepared, dried, exotic, baby, canned etc. We serve the French Riviera using our own fleet of experienced agents in the destination countries to Salads, Nuts, Seeds and Truffles. refrigerated vehicles, also delivering directly to Italy, ensure that your goods are cleared and delivered Sardinia and Corsica and further afield. promptly to your berth or anchorage. Cheese & Dairy 13 - 16 (Butter, Yoghurt, Milk, Ice Cream) Fresh, frozen, prepared and manufactured, UHT and *subject to import regulations branded goods International Foods and Ingredients 17 - 19 (Inc. Indian, Japanese, Oriental, Thai, South African) Pasta, rice, pulses, grains lentils, snails, seaweed, spices. Bread and Baking 20 - 21 Bread, biscuits, flours, mixes, patisserie, sundries, The Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, the complete pastry and canapé products. -

Singapore Hotel Guide

SINGAPORE HOTEL GUIDE 1 | P a g e Copyright @ Singapore Tourism Board All rights reserved. This document or any part thereof may not be reproduced for any reason whatsoever in any form or means whatsoever and howsoever without the prior written consent and approval of Singapore Tourism Board. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication (April 2018), the Singapore Tourism Board, its employees or agents shall not be responsible for any mistake or inaccuracy that may be contained herein and all such liability and responsibility are expressly disclaimed by these said parties. 2 | P a g e PREFACE The Singapore Hotel Guide is a voluntarily yet comprehensive reference guide to 225 gazetted hotels in Singapore, ranging from luxury hotels to boutique spaces, as well as budget accomodation. The guide contains key information including amenities, services and location of each hotel. This year’s edition also includes a comprehensive summary of the M.I.C.E. specifications in the annexes. All information in this guide are provided by respective hotels, and accurate at time of publication. As a code of practice, this guide takes guidance and recommendations from governing authorities and credible platforms including but not limited to the Urban Land Authority (URA) and VisitSingapore website. This guide does not purport to include all necessary provisions of a contract. Users of this guide are responsible for their correct application. 3 | P a g e CONTENT Preface 3 Hotel Landscape Overview -

Old Town Central

SELF-GUIDED WALKS CONTENTS 02 Time Travellers Modern-day Hong Kong may be best known for its glossy skyscrapers and world-class 10 attractions, but to understand how the city Crazy for Art became the bustling metropolis that it is today, one only need to pay a visit to Old Town Central. 20 Tasting Hong Kong One of the oldest yet also most dynamic districts in the city, Old Town Central – encompassing the sloped streets and 30 small alleys of Central and Sheung Wan – Treasure Hunt encapsulates Hong Kong’s rich and diverse spirit. A place where century-old temples 38 share the same streets as fashion-forward Highlight Route concept stores, or where authentic tea houses coexist with modern art galleries, this colourful neighbourhood is at once old and new while also being proudly local and unmistakably global. Immensely walkable and brimming with attractions, this neighbourhood is perfect to experience on foot. There’s plenty to discover here, from heritage buildings and art institutions to local eats and fun souvenirs. Whatever your interests are, this guide will lead you to some of the best things that Old Town Central has to offer. Have fun exploring. Disclaimer: Old Town Central is produced by Time Out Hong Kong and published by the Hong Kong Tourism Board. The Hong Kong Tourism Board shall not be responsible for any information described in the book, including those of shops, restaurants, goods, and services, and they do not represent and make guarantees concerning any such information regarding shops, restaurants, goods and services and so on, including commercial applicability, accuracy, adequacy and reliability, etc. -

GIC Product List Jun21

GIC PRODUCT LIST Code Description UOM Case Pack BDD001 L Green Chaokoh Coconut Juice w/ Meat = 大巧口椰肉椰汁 CS 24x17.5oz BDD002 S Green Chaokoh Coconut Juice w/ Meat = 小巧口椰肉椰汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD005 L Blue Chaokoh Coconut Juice w/ Jelly = 大巧口椰果椰汁 CS 24x17.5oz BDD006 S Blue Chaokoh Coconut Juice w/ Jelly = 小巧口椰果椰汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD010 L/Can Chaokoh Coconut Water= 大巧口椰子水 CS 24x520ml BDD011 S/Can Chaokoh Coconut Water = 小巧口椰子水 CS 24x350ml BDD015 L/TP Chaokoh Coconut Water = 大利樂包巧口椰子水 CS 12x1L BDD016 S/TP Chaokoh Coconut Water = 小利樂包巧口椰子水 CS 24x330ml BDD020 Chaokoh *Orig* Coco Milk Drink - 1L = 椰奶飲 CS 12x1L BDD021 Chaokoh *Orig* Coco Milk Drink - 330ml = 椰奶飲 CS 24x330ml BDD022 Chaokoh *Sweet Purple Potato* Coco Milk Drink = 紫薯椰奶飲 CS 12x1L BDD050 Foco Roasted Coconut Juice L = 大福口香烤椰汁 CS 24x17.6oz BDD051 Foco Roasted Coconut Juice S = 小福口香烤椰汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD055 L Foco Coconut Juice = 大福口椰汁 CS 24x17.6oz BDD056 S Foco Coconut Juice = 小福口椰汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD060 Foco Mangosteen Drink = 福口山竹汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD061 Foco Passion Fruit Drink = 福口百香果汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD062 Foco Mango Passion Fruit = 福口芒果百香果汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD063 Foco Mango Drink = 福口芒果汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD064 Foco Basil Seed Drink = 珍珠果露 CS 24x11.8oz BDD065 Foco Aloe Vera *Can* = 罐装福口蘆薈汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD066 Foco Pennywort = 福口青草汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD067 Foco Lychee Drink = 福口荔枝汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD068 Foco Soursop Juice = 福口番荔枝汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD069 Foco Thai Tea = 福口泰式奶茶 CS 24x11.8oz BDD070 Foco Tamarind Drink = 福口酸子汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD071 Foco Guava Drink = 福口芭樂汁 CS 24x11.8oz BDD120 Pink - Parrot Guava Juice -

Purveyors of the Finest Yacht Provisions

PURVEYORS OF THE FINEST YACHT PROVISIONS Suppliers to superyachts globally since 2003 Product Directory ABOUT US We work only with export approved suppliers who consistently produce, prepare and package provisions to the standards you require. PURVEYORS OF THE FINEST YACHT PROVISIONS Our mission is to deliver the world’s finest food to the most luxurious yachts afloat, wherever they happen to be. Behind this simple intention is a vast wealth of knowledge and experience. We know that superyacht owners and their guests are accustomed to demanding and receiving the very best of everything. Michelin-starred chefs, international food judges confirm that’s exactly what you’ll get from our finest producers. We work only with export-approved suppliers to the exacting standards you require. So, we can always meet your delivery times and you can exceed your guests’ expectations – year-round, world-wide. EMAIL US TO PLACE AN ORDER OR DISCUSS HOW WE CAN BE OF SERVICE, CONTACT OUR OFFICE ON: TEL: +44 (0) 1964 536668 EMAIL: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS Fresh, frozen, prepared and cured meats. Bread, biscuits, flours, mixes, patisserie, Coffee, tea, speciality teas, health powders. Certified Kosher and Halal. sundries, pastry and canapé products. Canned drinks, juices, squash, cordials, Special meats—from wagyu to exotic Full range of gluten free breads and mineral waters, fine and vintage wines, and rare breeds. bakery products. Colourings, flavourings, whiskies, cognac, beers and lagers, vanilla pods, paste and extract, liqueurs, smoking accessories, gelling agents and molecular gastronom. cigars and customised humidors. Fresh, frozen, prepared, smoked and marinated fish and seafood. -

White Anemone

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2014 White Anemone Zhe Chen University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Chen, Zhe, "White Anemone" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 5231. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/5231 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. White Anemone ! By Zhe Chen ! A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of English Language, Literature, and Creative Writing in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts at the ! UNIVERSITY OF WINDSOR ! ! ! ! Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2014 ! © 2014 Zhe Chen White Anemone by Zhe Chen ! APPROVED