White Anemone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

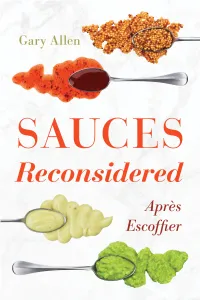

Sauces Reconsidered

SAUCES RECONSIDERED Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy General Editor: Ken Albala, Professor of History, University of the Pacific ([email protected]) Rowman & Littlefield Executive Editor: Suzanne Staszak-Silva ([email protected]) Food studies is a vibrant and thriving field encompassing not only cooking and eating habits but also issues such as health, sustainability, food safety, and animal rights. Scholars in disciplines as diverse as history, anthropol- ogy, sociology, literature, and the arts focus on food. The mission of Row- man & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy is to publish the best in food scholarship, harnessing the energy, ideas, and creativity of a wide array of food writers today. This broad line of food-related titles will range from food history, interdisciplinary food studies monographs, general inter- est series, and popular trade titles to textbooks for students and budding chefs, scholarly cookbooks, and reference works. Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam: Food and Drink in the Long Nine- teenth Century, by Erica J. Peters Three World Cuisines: Italian, Mexican, Chinese, by Ken Albala Food and Social Media: You Are What You Tweet, by Signe Rousseau Food and the Novel in Nineteenth-Century America, by Mark McWilliams Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America, by Bruce Kraig and Patty Carroll A Year in Food and Beer: Recipes and Beer Pairings for Every Season, by Emily Baime and Darin Michaels Celebraciones Mexicanas: History, Traditions, and Recipes, by Andrea Law- son Gray and Adriana Almazán Lahl The Food Section: Newspaper Women and the Culinary Community, by Kimberly Wilmot Voss Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits, and the Return of Artisanal Foods, by Suzanne Cope Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Years of World Culinary History, Cul- ture, and Social Influence, by Janet Clarkson Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy: From Kitchen to Table, by Kath- erine A. -

Number 35 July-September

THE BULB NEWSLETTER Number 35 July-September 2001 Amana lives, long live Among! ln the Kew Scientist, Issue 19 (April 2001), Kew's Dr Mike Fay reports on the molecular work that has been carried out on Among. This little tulip«like eastern Asiatic group of Liliaceae that we have long grown and loved as Among (A. edulis, A. latifolla, A. erythroniolde ), but which took a trip into the genus Tulipa, should in fact be treated as a distinct genus. The report notes that "Molecular data have shown this group to be as distinct from Tulipa s.s. [i.e. in the strict sense, excluding Among] as Erythronium, and the three genera should be recognised.” This is good news all round. I need not change the labels on the pots (they still labelled Among), neither will i have to re~|abel all the as Erythronlum species tulips! _ Among edulis is a remarkably persistent little plant. The bulbs of it in the BN garden were acquired in the early 19605 but had been in cultivation well before that, brought back to England by a plant enthusiast participating in the Korean war. Although not as showy as the tulips, they are pleasing little bulbs with starry white flowers striped purplish-brown on the outside. It takes a fair amount of sun to encourage them to open, so in cool temperate gardens where the light intensity is poor in winter and spring, pot cultivation in a glasshouse is the best method of cultivation. With the extra protection and warmth, the flowers will open out almost flat. -

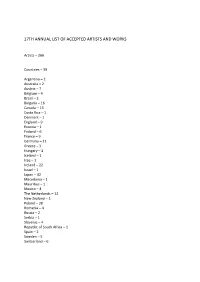

17Th Annual List of Accepted Artists and Works

17TH ANNUAL LIST OF ACCEPTED ARTISTS AND WORKS Artists – 266 Countries – 39 Argentina – 2 Australia – 2 Austria – 7 Belgium – 4 Brazil – 2 Bulgaria – 16 Canada – 13 Costa Rica – 1 Denmark – 1 England – 9 Estonia – 1 Finland – 6 France – 9 Germany – 11 Greece – 3 Hungary – 2 Iceland – 1 Iraq – 1 Ireland – 22 Israel – 1 Japan – 42 Macedonia – 1 Mauritius – 1 Mexico – 4 The Netherlands – 12 New Zealand – 1 Poland – 38 Romania – 4 Russia – 2 Serbia – 1 Slovenia – 4 Republic of South Africa – 1 Spain – 2 Sweden – 5 Switzerland – 6 Taiwan – 2 Thailand – 2 U. S. A. – 22 Venezuela – 1 Featured Artist DIMO KOLIBAROV, Bulgaria Cycle of prints Meetings with Bulgarian Printmaking Artists Presentation of the First Prize Winner of the 16th Mini Print Annual 2017 EVA CHOUNG – FUX, Austria Special Presentation FACULTY OF ARTS MARIA CURIE SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY Lublin, Poland Dr hab. Adam Panek The cycle of prints: 1. Triptych I – A, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 11 cm 2. Triptych I – B, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 9 cm 3. Triptych I – C, 2018, Linocut, 15,5 x 11 cm Dr hab. Alicja Snoch-Pawłowska The cycle of prints: 1. Diffusion 1, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm 2. Diffusion 2, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18 cm 3. Diffusion 3, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm Dr Amadeusz Popek The cycle of prints: 1. Mirage-Róża, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 2. Mirage-Pejzaż górski, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 3. Mirage, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm Mgr Andrzej Mosio The cycle of prints: 1. -

Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American Taxa

Mosyakin, S.L. 2018. Further new combinations in Anemonastrum (Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American taxa. Phytoneuron 2018-55: 1–11. Published 13 August 2018. ISSN 2153 733X FURTHER NEW COMBINATIONS IN ANEMONASTRUM (RANUNCULACEAE) FOR ASIAN AND NORTH AMERICAN TAXA SERGEI L. MOSYAKIN M.G. Kholodny Institute of Botany National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2 Tereshchenkivska Street Kiev (Kyiv), 01004 Ukraine [email protected] ABSTRACT Following the proposed re-circumscription of genera in the group of Anemone L. and related taxa of Ranunculaceae (Mosyakin 2016, Christenhusz et al. 2018) and based on recent molecular phylogenetic and partly morphological evidence, the genus Anemonastrum Holub is recognized here in an expanded circumscription (including Anemonidium (Spach) Holub, Arsenjevia Starod., Tamuria Starod., and Jurtsevia Á. Löve & D. Löve) covering members of the “Anemone ” clade with x=7, but excluding Hepatica Mill., a genus well outlined morphologically and forming a separate subclade (accepted by Hoot et al. (2012) as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (Spach) Juz. sect. Hepatica (Mill.) Spreng.) within the clade earlier recognized taxonomically as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (sensu Hoot et al. 2012). The following new combinations at the section and subsection ranks are validated: Anemonastrum Holub sect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone sect. Keiskea Tamura); Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov .; Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Arsenjevia (Starod.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Arsenjevia Starod.); and Anemonastrum [sect. Anemonastrum ] subsect. Himalayicae (Ulbr.) Mosyakin, comb. nov. ( Anemone ser. Himalayicae Ulbr.). The new nomenclatural combination Anemonastrum deltoideum (Hook.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone deltoidea Hook.) is validated for a North American species related to East Asian Anemonastrum keiskeanum (T. -

Newsletter Winter 2016 Issue

新 西 籣 東 增 會 館 THE TUNG JUNG ASSOCIATION OF NZ INC PO Box 9058, Wellington, New Zealand www.tungjung.org.nz Newsletter Winter 2016 issue ______ —— The Tung Jung Association of New Zealand Committee 2015—2016 President Gordon Wu 388 3560 Membership Kaye Wong 388 8060 Vice President Peter Wong 388 5828 Alex Chang 499 8032 Secretaries- English Valerie Ting 565 4421 Property Joe Chang 388 9135 Chinese Kevin Zeng 021 669628 Willie Wong 386 3099 Treasurer Robert Ting 478 6253 Newsletter Gordon Wu 388 3560 Assistant treasurer Virginia Ng 232 9971 Peter Moon 389 8819 Social Peter Wong 388 5828 Website Gordon Wu 388 3560 Elaine Chang 388 9135 Peter Moon 389 8819 Andrina Chang 499 8032 Valerie Ting 565 4421 Public Gordon Wu 388 3560 Peter Moon 389 8819 relations Please visit our website at http://www.tungjung.org.nz 1 President’s report……….. The past three months we have had extremely good weather and a lot of things have been happening which has made time go by very quickly. By the time you receive this newsletter, winter will have arrived and you will have time to read it! Since the last newsletter, the Association was invited to attend the launch of a rewrite of a book written by an Australi- an author on Chinese ANZAC’s. He had omitted that there were also New Zealand ANZAC’s, so it was rewritten to include the New Zealand soldiers during World War One. Robert Ting attended on behalf of the Association. A day excursion to the Wairarapa was made in early March. -

Anemone Acutiloba – Hepatica

Friends of the Arboretum Native Plant Sale Anemone acutiloba – Hepatica COMMON NAME: Hepatica, Sharp-lobed hepatica SCIENTIFIC NAME: Anemone acutiloba – the Greek word anemos is wind and acutiloba refers to the pointed leaves. The common name of hepatica comes from the fancied resemblance of the 3-lobed leaves to the liver. FLOWER: white, pink, lavender with six (usually) petal-like sepals. The color tends to fade with age. BLOOMING PERIOD: April, but maybe March with global warming! This is one of the earliest spring flowers. SIZE: 4 to 6 inches BEHAVIOR: This is a perennial herb with its distinctive 3-lobed leaves and fibrous roots. It will spread from seed and should be divided in fall. SITE REQUIREMENTS: Does best in rich, moist soil and dense shade of maple forests, but tolerates less shady habitats and drier, rocky soils. Look for it on steep, rocky hillsides and steep banks of creeks. NATURAL RANGE; Nova Scotia to northern Florida, west to Manitoba, Iowa, Missouri and even in Alaska. In Wisconsin it is more common in the southern 2/3 of the state. SPECIAL FEATURES: Old leaves may still be present in early spring, but will be looking kind of coppery. Then furry stems unfurl and hold the fragrant pastel flowers. The new leaves appear after flowering and will remain sort of green until the following spring. SUGGESTED CARE: Provide ample water in spring and fall, especially the first few years. Cover in winter with light mulch of maple leaves, but remove the mulch in mid to late March. COMPANION PLANTS: trillium, Solomon’s plume, toothwort, Dutchman’s breeches, spring beauty, wild geranium, bloodroot, troutlily, bedstraw, rue anemone SPECIAL NOTE: There is a similar specials, Anemone Americana, with round-lobed leaves. -

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

Adorable Anemone

inspirationalabout this guide | about anemones | colour index | species index | species pages | icons | glossary invertebratesadorable anemonesa guide to the shallow water anemones of New Zealand Version 1, 2019 Sadie Mills Serena Cox with Michelle Kelly & Blayne Herr 1 about this guide | about anemones | colour index | species index | species pages | icons | glossary about this guide Anemones are found everywhere in the sea, from under rocks in the intertidal zone, to the deepest trenches of our oceans. They are a colourful and diverse group, and we hope you enjoy using this guide to explore them further and identify them in the field. ADORABLE ANEMONES is a fully illustrated working e-guide to the most commonly encountered shallow water species of Actiniaria, Corallimorpharia, Ceriantharia and Zoantharia, the anemones of New Zealand. It is designed for New Zealanders like you who live near the sea, dive and snorkel, explore our coasts, make a living from it, and for those who educate and are charged with kaitiakitanga, conservation and management of our marine realm. It is one in a series of e-guides on New Zealand Marine invertebrates and algae that NIWA’s Coasts and Oceans group is presently developing. The e-guide starts with a simple introduction to living anemones, followed by a simple colour index, species index, detailed individual species pages, and finally, icon explanations and a glossary of terms. As new species are discovered and described, new species pages will be added and an updated version of this e-guide will be made available. Each anemone species page illustrates and describes features that will enable you to differentiate the species from each other. -

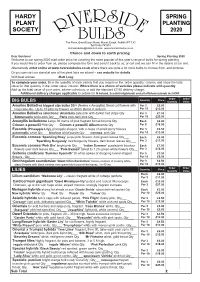

Daffodils & Narcissus

HARDY SPRING PLANT PLANTING SOCIETY 2020 The Flints, Brent Eleigh Road, Monks Eleigh, Suffolk IP7 7JG Tel 01449 741551 [email protected] www.riversidebulbs.co.uk Choice and down to earth pricing Dear Gardener Spring Planting 2020 Welcome to our spring 2020 mail order price list covering the more popular of this year’s range of bulbs for spring planting. If you would like to order from us, please complete the form and send it back to us, or call and we can fill in the details at our end. Alternatively order online at www.riversidebulbs.co.uk where there are quite a lot more bulbs to choose from, and pictures. Or you can visit our stand at one of the plant fairs we attend – see website for details With best wishes Matt Long To complete your order, fill in the quantity of each variety that you require in the ‘order quantity’ column, and show the total value for that quantity in the ‘order value’ column. Where there is a choice of varieties please indicate with quantity Add up the total value of your order, advise collection, or add the standard £7.50 delivery charge. Additional delivery charges applicable to orders for N Ireland, Scottish Highlands and all offshore islands incl IOW. Order Order Quantity Price BIG BULBS Quantity Value Amarine Belladiva biggest size bulbs 20/+ (Nerine x Amaryllis) Great cut flowers with Per 3 £6.00 long vase-life. Up to 10 pink lily flowers on 60cm stems in autumn Per 10 £15.00 Amarine Belladiva selections: Anastasia pale pink with darker mid stripe Qty___ Per 3 £7.50 Emmanuelle white-pink Qty___ -

Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

A “Truly Unmonastic Way of Life”: Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hannah Elizabeth Ewing Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Timothy Gregory, Advisor Professor Anthony Kaldellis Professor Alison I. Beach Copyright by Hannah Elizabeth Ewing 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines twelfth-century Byzantine writings on monasticism and holy men to illuminate monastic critiques during this period. Drawing upon close readings of texts from a range of twelfth-century voices, it processes both highly biased literary evidence and the limited documentary evidence from the period. In contextualizing the complaints about monks and reforms suggested for monasticism, as found in the writings of the intellectual and administrative elites of the empire, both secular and ecclesiastical, this study shows how monasticism did not fit so well in the world of twelfth-century Byzantium as it did with that of the preceding centuries. This was largely on account of developments in the role and operation of the church and the rise of alternative cultural models that were more critical of traditional ascetic sanctity. This project demonstrates the extent to which twelfth-century Byzantine society and culture had changed since the monastic heyday of the tenth century and contributes toward a deeper understanding of Byzantine monasticism in an under-researched period of the institution. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family, and most especially to my parents. iii Acknowledgments This dissertation is indebted to the assistance, advice, and support given by Anthony Kaldellis, Tim Gregory, and Alison Beach. -

Summer Flowering 2020 A4 Reduced Size 2.Pdf

Brand New Showcases Brand New Pre-Packs Bulbs ‘In the Green’ Summer Flowering Bulbs Loose Bulbs Wholesale Catalogue 2020 Tel: 01406 550341 - Fax: 01406 550340 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gedneybulb.co.uk See our range of Summer Flowering Bulbs inside... 2 Pre-Packs Welcome to the all new, bigger than ever Colourful Gardens Summer Bulb Pre-Pack range! All of our Summer Bulb pre-packs will have the same style of packaging as our popular Spring Bulb collection, giving your customers a recognised brand to purchase. This year we are offering more pre-pack varieties than we’ve ever offered - including a large selection of Gladioli, tried and tested favourites like Liatris and Crocosmia, then along with some new varieties such as Mirabilis, Anemone and Oxalis - all complete with full colour picture cards to create a high impact, low effort display. All pre-packs are priced at £1.15 each, in minimum quantities of 15 per variety - these come in a cardboard capper box. Pre-packs provide a great opportunity to offer a multi-buy, with a suggested selling price of £2.99 each or 4 for £10. You can choose from... 1 - Pick Your Own: You may select any of the 60 available pre-pack varieties shown in the images below and on the page opposite. You must order a minimum of 15 pre-packs per variety and a minimum of 4 varieties (total of 60 pre-packs) 2 - Bulb Collections: Each of these collections contains 4 different varieties, with 15 pre-packs per variety. Total of 60 pre-packs. -

Explorations the Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities for the State of North Carolina

Volume X 2015 Explorations The Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities for the State of North Carolina http://uncw.edu/csurf/Explorations/explorations.html [email protected] Center for the Support of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships UNCW Honors College Randall Library, room 2007 University of North Carolina Wilmington Wilmington, NC 28403 copyright © 2015 by the University of North Carolina Wilmington Cover photographs: Beach: Logan P. Prochaska Piedmont: Logan P. Prochaska Mountain: Logan P. Prochaska ISBN: 978-0-9908-932-2-6 Original Design by The Publishing Laboratory Department of Creative Writing University of North Carolina Wilmington 601 South College Road Wilmington, North Carolina 28403 www.uncw.edu/writers Produced by Center for the Support of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships Honors College University of North Carolina Wilmington 601 South College Road Wilmington, North Carolina 28403 http://uncw.edu/csurf/Explorations/explorations.html Staff Editor-in-Chief Katherine E. Bruce, PhD Director, Honors College and Center for the Support of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships Professor of Pyschology University of North Carolina Wilmington Visual Arts Editor Edward Irvine, MPD Associate Professor of Studio Art University of North Carolina Wilmington Consultant Jennifer Horan, PhD Associate Professor of Political Science Associate Director, Honors College University of North Carolina Wilmington Copy Editor Catharine Nealley Psychology Graduate Student CSURF Graduate Assistant University of North Carolina