June Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Lesbian and Gay Musical Preferences and 'LGB Music' in Flanders

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, vol.9 - nº2 (2015), 207-223 1646-5954/ERC123483/2015 207 Into the Groove - Exploring lesbian and gay musical preferences and 'LGB music' in Flanders Alexander Dhoest*, Robbe Herreman**, Marion Wasserbauer*** * PhD, Associate professor, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) ** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) *** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) Abstract The importance of music and music tastes in lesbian and gay cultures is widely documented, but empirical research on individual lesbian and gay musical preferences is rare and even fully absent in Flanders (Belgium). To explore this field, we used an online quantitative survey (N= 761) followed up by 60 in-depth interviews, asking questions about musical preferences. Both the survey and the interviews disclose strongly gender-specific patterns of musical preference, the women preferring rock and alternative genres while the men tend to prefer pop and more commercial genres. While the sexual orientation of the musician is not very relevant to most participants, they do identify certain kinds of music that are strongly associated with lesbian and/or gay culture, often based on the play with codes of masculinity and femininity. Our findings confirm the popularity of certain types of music among Flemish lesbians and gay men, for whom it constitutes a shared source of identification, as it does across many Western countries. The qualitative data, in particular, allow us to better understand how such music plays a role in constituting and supporting lesbian and gay cultures and communities. -

GREG KURSTIN Her

ISSUE #26 MMUSICMAG.COM ISSUE #26 MMUSICMAG.COM PRODUCER How was it producing Kelly Clarkson? they’d be flawless. Other than layering and She can really sing, that’s for sure. She’s adding in harmonies, I don’t think there cool, professional and easy to work with. was any vocal editing. She’ll do a few takes to get warmed up and after that, you’re getting awesome take after How did you produce Tegan and Sara? awesome take. We did some vocal comping, They’ve been making records for a while but nothing extensive. and wanted to expand their sound and try something different. They had heard a lot of What’s the story behind the megahit music that I had worked on and reached out “Stronger (What Doesn’t Kill You)”? to me. A lot of their demos felt very synth- I was both the producer and a songwriter, based, and being a synth nerd, I got excited. but there was a somewhat finished version We ended up doing eight songs together. I of that song that existed before I came into played everything except for drums on the the picture. It was slower, and the chords record. I love their songwriting and I’m proud and feel of the track were different from the of what we did. version that was released. The label wasn’t convinced it would work for her. I had Kelly Clarkson What about producing the Flaming Lips? previously worked with Kelly on “Honestly” I had played with the Lips, and sometime and it went really well, so her A&R played as possible. -

A7fgleefaklatit" "

HOT DANCE/ELECTRONIC SONGSTM DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUMST" LIST TITLECERTIFICATION Artist LAST I THIS ARTISTCERTIFICATION MEEK PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION IABEL WEEK WEER IMPRINT/DISTRIBUTING LABEL (HART NEW LA ROUX Trouble In Paradise j LATCHA Disclosure Featuring Sam Smith I 4S IE4OGISINCHLIqTIPILMIENDA M POSTOOR/CHERWIREE/INTERSCOPEAGA 0 DKUOSUKOILLITISCEGLARTENCESSINININNIEN 2 2 LINDSEY STIRLING Shatter Me 13 In SUMMERS Calvin Harris , 20 LINDSEYSTOmP 0 (MARRS KAMM TUN. DECONSTRUCTION/ELY MANTRA/ROC NAROMOLUMBIA DISCLOSURE Settle 60 TURN DOWN FOR WHAT DJ Snake &cLoiLlulop lO ME IHOO/PMR/04RRYIRE 17iNTF RSCOPF /oGA 3 3 3 A 33 DI SRAM .I.SMII H (1.14.94114.W.GRKAHOSE.M. BIUSSO) A1 LADY GAGA ARTPOP 37 RATHER BE STREAMLINE/IA.5(0PC/. Clean Bandit Featuring Jess Glynne 4 25 O 0 0 01111JRATIERSONA.CHATTO (LNANERAPMTERSON.N.MARSHALL) BIG BEAT/RRP DAFT PUNKARandom Access Memories 63 5 DAFT LIFE/COLUMBIA BREAK FREE AsLA,.......arih,Aoirtiaza Grande Featuring 4 4 O La Roux ZEDOMAx MARTIN (A2 0 0 C DEADMAUS while(1<2) 6 A SKY FULL OF STARS Coldplay TAAUSTRAP/ASTRALWERXSKAINTOL 6 4 0 0 WOURNIAPIPPNRUNTILIANIONNEARAPINNUIWIEWILILDAWIDUAIWRWIN,IN me.otoPt N.LL, Finds AVICII True 45 WASTED Tiesto Featuring Matthew Koma 0 PRMONSLAND 6 7 7 5 14 ILIEWIMILUIESTOMOR1STACINDIRWIVIUNESULAWKIKG4S1 NAM INIDNIVIINAAWERICASIPN, `Paradise' SYLVAN ESSO Sylvan Esso 11 8 PARTISAN HIDEAWAY Kiesza O R.SAFUNI IK.R.ELLESTAD.R.SAFUNI) LORAL LEGENDNITH . BROADWAWISUND/REPUBUC 8 14 La Roux follows its 0 0 12 KIESZA Hideaway (EP) 3 0 LONA LEGENDATHR BROADWAY/614ND Grammy -winning self -titled 8 9 DARE (LA LA LA) Shakira 5 18 Di LK.SoauSAR.CR4IGHIARAISNOUKIRLUANOLPRIPTEALLINAITIXXIIMNARINEGIRWICIDL Al NA debut with its first No.1 10 SKRILLEX Recess 19 BEAT/OWSLA/ATLANTKAG onDance/Electronic WAVES Mr. -

Places to Go, People To

Hanson mistakenINSIDE EXCLUSIVE:for witches, burned. VerThe Vanderbilt Hustler’s Arts su & Entertainment Magazine s OCTOBER 28—NOVEMBER 3, 2009 VOL. 47, NO. 23 VANDY FALL FASHION We found 10 students who put their own spin on this season’s trends. Check it out when you fl ip to page 9. Cinematic Spark Notes for your reading pleasure on page 4. “I’m a mouse. Duh!” Halloween costume ideas beyond animal ears and hotpants. Turn to page 8 and put down the bunny ears. PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, OCTOBER 29 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 30 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31 The Regulars The Black Lips – The Mercy Lounge Jimmy Hall and The Prisoners of Love Reunion Show The Avett Brothers – Ryman Auditorium THE RUTLEDGE The Mercy Lounge will play host to self described psychedelic/ There really isn’t enough good to be said about an Avett Brothers concert. – 3rd and Lindsley 410 Fourth Ave. South 37201 comedy band the Black Lips. With heavy punk rock infl uence and Singing dirty blues and southern rock with an earthy, roots The energy, the passion, the excitement, the emotion, the talent … all are 782-6858 mildly witty lyrics, these Lips are not Flaming but will certainly music sound, Jimmy Hall and his crew stick to the basics with completely unrivaled when it comes to the band’s explosive live shows. provide another sort of entertainment. The show will lean towards a songs like “Still Want To Be Your Man.” The no nonsense Whether it’s a heart wrenchingly beautiful ballad or a hard-driving rock punk or skaa atmosphere, though less angry. -

Twinning with Tegan and Sara

TEGAN ANDSARA TWINNING WITH Hey Lady!•DETOXifyingGenderAltQueerFest June / July2016 Presented by PinkPlayMags For daily and weekly event listings visit www.thebuzzmag.ca 2 June / July 2016 theBUZZmag.ca theBUZZmag.ca June / July 2016 3 Issue #013 The Editor Here we go again. It’s summer, and Publisher + Creative Director: time to show our Pride. Here in Toronto Antoine Elhashem we’re lucky enough to have one of the Editor-in-Chief: Bryen Dunn biggest Pride festivals in the world, Art Director: and this month the organization has Mychol Scully declared June as the first ever Pride General Manager: Kim Dobie Month. Sales Representatives: In celebration of this milestone we’ve had our Events Carolyn Burtch, Michael Wile, Sami Boudjenane Editor compile a special selection of Pride related events in the city for our Wigged Out column. This Events Editor: is in addition to our extensive regular events listing. Sherry Sylvain Scan through as there will certainly be something for Counsel: everyone from partiers to parents. Lai-King Hum, Hum Law Firm For our feature articles we had Daniela Costa chat with Tegan Quin, from the queer twin Canadian music Regular Columnists: duo Tegan and Sara. They have a new album out Cat Grant, Paul Bellini, Boyd Kodak, Sherry Sylvain, that includes the catchy single, “Boyfriend”, and you Donnarama can find out how to attend their private show here Feature Writers: in Toronto the end of this month. As well, Raymond Helkio chatted with Detox from RuPaul’s Drag Race Daniela Costa, Raymond Helkio about the gender myth, pride and living life large. -

2013 May 7 May 14

MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES • MUSIC • FILM • MERCHANDISE • NEW RELEASES STREET DATES: MAY 7 MAY 14 ORDERS DUE: APRIL 9 ORDERS DUE: APRIL 16 ISSUE 10 wea.com 2013 5/7/13 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ORDERS ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP DUE Campbell, Craig Never Regret BGP CD 093624945673 534592 $13.99 4/10/13 Fitz & The Tantrums More Than Just A Dream NEK CD 075678731921 534918 $13.99 4/10/13 More Than Just A Dream (180 Gram Fitz & The Tantrums NEK A 075678731853 534918 $19.98 4/10/13 Vinyl) Redman, Joshua Walking Shadows NON CD 075597960938 532288 $16.98 4/10/13 Straight No Chaser Under The Influence ATL CD 075678762185 532676 $18.98 4/10/13 Last Update: 03/26/13 For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. ARTIST: Craig Campbell TITLE: Never Regret Label: BGP/Bigger Picture Group Config & Selection #: CD 534592 Street Date: 05/07/13 Order Due Date: 04/10/13 UPC: 093624945673 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $13.99 Alphabetize Under: C TRACKS Compact Disc 1 01 Truck-N-Roll 07 Topless 02 Keep Them Kisses Comin' 08 When Ends Don't Meet 03 When She Grows Up 09 Outta My Head 04 Tomorrow Is Gone 10 That's Why God Made A Front Porch 05 Never Regret 11 You Can Come Over 06 My Baby's Daddy 12 Lotta Good That Does Me Now FEATURED TRACKS Outta My Head ALBUM FACTS Genre: Country Producers: Keith Stegall (Grammy winner for Zac Brown Band's Uncaged and has 50 #1 records, amoung those are from Alan Jackson) and Matt Rovey (2-Year CCMA "Album Of the Year" award winner). -

Music Policy

JOY Music Policy Revised July 2016 Intent JOY is a volunteer-based community radio station committed to providing a voice for the diverse gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer communities, enabling freedom of expression, the breaking down of isolation and the celebration of our culture, achievements and pride. At the same time, community broadcasters are renowned for supporting new, local, independent and Australian music. Many musicians have had their first airplay and interviews on our station. JOY is in a position to play and engage with a broad range of musical styles across the station. JOY’s support of the music industry is one of the key reasons people listen and in return JOY receives support from some of the world’s most high profile musicians. These same musicians are a highly visible and vocal group of allied supporters for our community. Purpose To ensure that JOY • continues to play a diverse range of music throughout all of our programming • supports musicians, writers and producers who publicly identify or are otherwise considered as part of the gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans, intersex or Queer (LGBTIQA+) communities • supports musicians, writers and producers who publically align and support the LGBTIQA+ communities • supports local musicians, and • Complies with the 25% Australian music requirement of the Codes by aiming for 30% Australian music across all general programming. Scope All programming. Definitions 1. Australian content is defined as • Music performed by bands and artists who do the majority of their recording in Australia or New Zealand, regardless of national origins (for examples, refer Appendix 4.1) • Music by bands or artists considered Australian or New Zealander due to their national origins, regardless of where they live and record (for examples, refer Appendix 4.2) 2. -

Manufacturing Is Back—But Where Are the Jobs? 0 I

0 iF I. V,V • V’ MANUFACTURING $4.99US $5.99CAN IS BACK—BUT WHERE ARE THE JOBS? BY RANA FOROOHAR & BILL SAPORITO o 92567II 10090 3 www.tImecom The Culture Music Two of Hearts. Tegan and Sara take the long road to the stars By Jesse Dorris IN GREEK MYTHOLOGY, THE DIOSCURI stantly recorded themselves with a Fisher- ments alongside radio-ready gems like were twin sons of Zeus who, upon death, Price microphone. “We were also obsessed “Back in Your Head.” But sales remained transformed into the Gemini constella with recording TV shows on our portable moderate. Tegan and Sara had stalled as tion, a navigational tool for sailors. They stereo,” Sara says, “just the audio, and then a critically respected opening act, filling also appeared as St. Elmo’s fire, scram we would lie in bed and listen to them.” small venues in college towns, waiting bling compasses. They showed the way They began recording songs of their own, for the stars to align. “There have been yet often confused travelers. Either way, written separately but played together. so many points,” Tegan says, “when you no one could look away from them. “We would make our own demo tapes”— think, Should we just accept that we’re an The pop-rock duo Tegan and Sara offers two albums’ worth, recorded at their high underground, cult-status-type band and a similar combination of direction and school’s studio—”make artwork for them just be happy with it? Do what we love dazzle. At 32, the twin sisters have spent and sell them at school,” Sara says. -

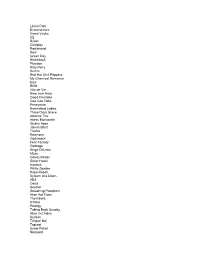

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay Radiohead Korn Green Day Nickelback Placebo Katy Perry Kumm Red Hot Chili Peppers My Chemical Romance Eels REM Vita de Vie Nine Inch Nails Good Charlotte Goo Goo Dolls Pennywise Barenaked Ladies Three Days Grace Alkaline Trio Alanis Morissette Guano Apes James Blunt Travka Reamonn Godsmack Fear Factory Garbage Kings Of Leon Muse Gandul Matei Sister Hazel Incubus White Zombie Papa Roach System of a Down AB4 Oasis Seether Smashing Pumpkins Alien Ant Farm The Killers Ill Nino Prodigy Taking Back Sunday Alice in Chains Kutless Timpuri Noi Taproot Snow Patrol Nonpoint Dashboard Confessional The Cure The Cranberries Stereophonics Blink 182 Phish Blur Rage Against the Machine Gorillaz Pulp Bowling For Soup Citizen Cope Manic Street Preachers Luna Amara Nirvana The Verve Breaking Benjamin Chevelle Modest Mouse Jeff Buckley Beck Arctic Monkeys Bloodhound Gang Sevendust Coma Lostprophets Keane Blue October 30 Seconds to Mars Suede Collective Soul Kill Hannah Foo Fighters The Cult Feeder Veruca Salt Skunk Anansie 3 Doors Down Deftones Sugar Ray Counting Crows Mushroomhead Electric Six Filter Lynyrd Skynyrd Biffy Clyro Death Cab For Cutie Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds The White Stripes James Morrison Texas Crazy Town Mudvayne Placebo Crash Test Dummies Poets Of The Fall Jason Mraz Linkin Park Sum 41 Grimus Guster A Perfect Circle Tool The Strokes Flyleaf Chris Cornell Smile Empty Soul Audioslave Nirvana Gogol Bordello Bloc Party Thousand Foot Krutch Brand New Razorlight Puddle Of Mudd Sonic Youth -

Anti-Valentines-Day-Playlist.Pdf

Anti-Valentine's Day LENGTH TITLE ARTIST bpm 4:32 Don't Cha The Pussycat Dolls 120 3:58 Say Something Loving The xx 130 3:03 This Is Not About Us Banks 100 Knowing Me, Knowing You (Almighty Definitive Radio 3:47 Edit) Abbacadabra 128 3:24 I Was a Fool Tegan and Sara 176 4:19 It Must Have Been Love Roxette 81 3:10 That's The Way Love Dies (feat. Tiger Rosa) Buck 65 170 3:11 Only War (feat. Tiger Rosa) Buck 65 168 3:42 Your Love Is A Lie Simple Plan 160 3:23 Bleeding Love - Vinylmoverz Hands Up Edit Swing State 136 4:14 Only Love Can Break Your Heart Jenn Grant 111 6:05 Hearts A Mess Gotye 125 4:22 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover G. Love & Special Sauce 92 3:42 Jealous Nick Jonas 93 I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For - 4:37 Remastered U2 101 3:07 Music Is My Hot, Hot Sex CSS 100 3:45 Foundations - Clean Edit Kate Nash 84 4:22 He Wasn't Man Enough Toni Braxton 88 3:49 Same Old Love Selena Gomez 98 3:34 Don't Wanna Know Maroon 5 100 5:20 Boy From School Hot Chip 126 5:48 Somebody Else The 1975 101 3:27 So Sick Ne-Yo 95 3:55 Sugar Maroon 5 120 3:42 Heartless Kris Allen 95 Here Without You - Alex M. & Marc Van Damme 3:26 Remix Edit Andrew Spencer 142 4:13 Let Her Go Passenger 75 2:28 I Will Survive Me First and the Gimme Gimmes 121 3:23 Baby Don't Lie Gwen Stefani 100 3:50 FU Miley Cyrus 190 5:12 I'd Do Anything For Love (But I Won't Do That) D.J. -

Playnetwork Business Mixes

PlayNetwork Business Mixes 50s to Early 60s Marketing Strategy: Period themes, burgers and brews and pizza, bars, happy hour Era: Classic Compatible Music Styles: Fun-Time Oldies, Classic Description: All tempos and styles that had hits Rock, 70s Mix during the heyday of the 50s and into the early 60s, including some country as well Representative Artists: Elvis, Fats Domino, Steve 70s Mix Lawrence, Brenda Lee, Dinah Washington, Frankie Era: 70s Valli and the Four Seasons, Chubby Checker, The Impressions Description: An 8-track flashback of great music Appeal: People who can remember and appreciate from the 70s designed to inspire memories for the major musical moments from this era everyone. Featuring hits and historically significant album cuts from the “Far Out!,” Bob Newhart, Sanford Feel: All tempos and Son era Marketing Strategy: Hamburger/soda fountain– Representative Artists: The Eagles, Elton John, themed cafes, period-themed establishments, bars, Stevie Wonder, Jackson Brown, Gerry Rafferty, pizza establishments and clothing stores Chicago, Doobie Brothers, Brothers Johnson, Alan Parsons Project, Jim Croce, Joni Mitchell, Sugarloaf, Compatible Music Styles: Jukebox classics, Donut Steely Dan, Earth Wind & Fire, Paul Simon, Crosby, House Jukebox, Fun-Time Oldies, Innocent 40s, 50s, Stills, and Nash, Creedence Clearwater Revival, 60s Average White Band, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Electric Light Orchestra, Fleetwood Mac, Guess Who, 60s to Early 70s Billy Joel, Jefferson Starship, Steve Miller Band, Carly Simon, KC & the Sunshine Band, Van Morrison Era: Classic Feel: A warm blanket of familiar music that helped Description: Good-time pop and rock legends from define the analog sound of the 70s—including the the mid-60s through the early-to-mid-70s that marked one-hit wonders and the best known singer- the end of an era. -

Lilith 2010 Alert***Lilith 2010 Alert***Lilith 2010 Alert The

LILITH 2010 ALERT***LILITH 2010 ALERT***LILITH 2010 ALERT THE 2010 LILITH TOUR ANNOUNCES COMPLETE LIST OF TOUR DATES SUPERSTAR RIHANNA ADDED TO LINE-UP Limited Ladies Night 4-Pack Ticket Offer For $99 April 12, 2010 (New York, NY) –The 2010 Lilith Tour has revealed the full list of tour dates for all 36 cities that the Live Nation produced festival will hit this summer, with city-by-city line-up details being updated weekly on LilithFair.com. Additionally, superstar Rihanna will take a break from her recently announced North American tour to make a special appearance at Lilith’s Salt Lake City date on Monday, July 12. Tickets are already on sale for many markets, with the remaining dates going on-sale beginning Saturday, April 17 via LilithFair.com and LiveNation.com. A limited number of Ladies Night 4-Pack ticket packages will be offered for $99* that includes 4 lawn tickets to participating venues, while supplies last. Click HERE to watch a special performance by Lilith co-founder Sarah McLachlan of her hit song “Angel” with special guest and fellow Lilith artist Emmylou Harris on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, which aired on March 25, 2010 on ABC. *Quantities are limited and additional fees may apply. Below is the full list of dates and cities the 2010 Lilith Tour will visit this summer. There will be 11 artists on each date, with only two consistencies per show: the Lilith Local Talent Search Ourstage.com winner who starts the day and headliner Sarah McLachlan. Visit LilithFair.com for more information.