A Journal of the California Native Plant Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antileishmanial Compounds from Nature - Elucidation of the Active Principles of an Extract from Valeriana Wallichii Rhizomes

ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 Eingereicht am ....................................... bei der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie 1. Gutachter Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Gutachter ........................................ der Dissertation 1. Prüfer Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Prüfer ......................................... 3. Prüfer ......................................... des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums Datum des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums .................................................. Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am .................................................. "Wer nichts als Chemie versteht, versteht auch die nicht recht." Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799) DANKSAGUNG Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde am Institut für Pharmazie und Lebensmittelchemie der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg auf Anregung und unter Anleitung von Frau Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe und finanzieller Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 630) angefertigt. Ich -

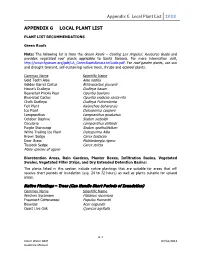

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX G LOCAL PLANT LIST PLANT LIST RECOMMENDATIONS Green Roofs Note: The following list is from the Green Roofs – Cooling Los Angeles: Resource Guide and provides vegetated roof plants applicable to Santa Barbara. For more information visit, http://www.fypower.org/pdf/LA_GreenRoofsResourceGuide.pdf. For roof garden plants, use sun and drought tolerant, self-sustaining native trees, shrubs and ecoroof plants. Common Name Scientific Name Gold Tooth Aloe Aloe nobilis Golden Barrel Cactus Echinocactus grusonii Hasse’s Dudleya Dudleya hassei Beavertail Prickly Pear Opuntia basilaris Blue-blad Cactus Opuntia violacea santa-rita Chalk Dudleya Dudleya Pulverulenta Felt Plant Kalanchoe beharensis Ice Plant Delosperma cooperii Lampranthus Lampranthus productus October Daphne Sedum sieboldii Oscularia Lampranthus deltoids Purple Stonecrop Sedum spathulifolium White Trailing Ice Plant Delosperma Alba Brown Sedge Carex testacea Deer Grass Muhlenbergia rigens Tussock Sedge Carex stricta Many species of agave Bioretention Areas, Rain Gardens, Planter Boxes, Infiltration Basins, Vegetated Swales, Vegetated Filter Strips, and Dry Extended Detention Basins: The plants listed in this section include native plantings that are suitable for areas that will receive short periods of inundation (e.g. 24 to 72 hours) as well as plants suitable for upland areas. Native Plantings – Trees (Can Handle Short Periods of Inundation) Common Name Scientific Name Western Sycamore Platanus racemosa Freemont Cottonwood Populus fremontii -

Chapter 1 Purpose and Need

TESTIMONY OF STEPHEN GRINNELL, P.E., YUNG-HSIN SUN, Ph.D., AND STUART ROBERTSON, P.E. YUBA RIVER INDEX: WATER YEAR CLASSIFICATIONS FOR YUBA RIVER PREPARED FOR YUBA COUNTY WATER AGENCY PREPARED BY BOOKMAN-EDMONSTON ENGINEERING, INC. Unpublished Work © November 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................1 SACRAMENTO VALLEY INDEX AND SAN JOAQUIN RIVER INDEX .................................................1 NEED FOR YUBA RIVER INDEX ..................................................................................................................2 DISTRIBUTION OF YUBA RIVER ANNUAL UNIMPAIRED FLOWS...........................................................................3 FUNCTIONS AND PURPOSES OF EXISTING FACILITIES..........................................................................................4 YUBA RIVER INDEX........................................................................................................................................6 INDEX DESIGN ...................................................................................................................................................6 INDEX DEFINITION .............................................................................................................................................7 WATER YEAR CLASSIFICATIONS OF YUBA RIVER ..............................................................................................8 -

The Mighty Yuba River

The Mighty Yuba River The sounds of the Yuba River as it slowly winds its way down stream, are both peaceful and relaxing. But, upstream, the river sings quite a different song. The river begins as three separate forks, the north, south, and middle, high in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The forks flow wildly through canyons and channels, over boulders and rock bars, and will occasionally rest in pools of clear green water. There are two stories as to how the river was named. One story, tells of a scoutinggp expedition finding wild g gpgrapes growing on the river’s banks. They called the river, Rio de las Uvas (the grapes). “Uvas” was later changed to Yuba. A second story, tells of an ancestral village named Yuba, belonging to the Maidu tribe, that was located where the Feather River joins the Yuba River. The river has changed a great deal over the years. It was mined extensively during the Gold Rush and once ran abundant with Chinook salmon and steelhead trout. Mining on the Yuba River is more recreational today and the Chinook salmon and steelhead still have a strong presence in the river. The Yuba River is also part of the Yuba Watershed. It’s truly an amazing river that has many more stories to tell. th ©University of California, 2009, Zoe E. Beaton. Yuba River Education Center 6 - Yuba River #1- YREC North Fork of the Yuba River Middle Fork of the Yuba River South Fork of the Yuba River ©University of California, 2009, Zoe E. Beaton. Yuba River Education Center 6th Yuba River #2- YREC . -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Yuba River Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan

CHAPTER 7 – INTERPRETIVE PLAN Interpretation Interpretation is ‘value added’ to a byway experience. Effective interpretation forges a connection between the visitor and the byway. It provides a memorable moment for the visitor to take home – a thought, image or a concept that reminds them of their experience. It helps them to recognize the byway as a unique and special place and to see and appreciate attributes that may not be readily apparent. It encourages them to spend more time and to return or tell their friends about their experience. The sustainable recreation framework (2010) highlights interpretation as one of the most important agency tools to develop deeper engagement between Americans and their natural resources. Visitor Needs Visitor needs are typically arranged into a hierarchy: orientation, information and interpretation. Once a visitor is comfortable and oriented they are receptive to interpretive information. Orientation and general information will be addressed as part of this interpretive planning effort. Orientation The first priority for visitors is to understand where they are and where they can meet their basic needs – restrooms, food, lodging. This orientation information is typically placed at either end of a byway in the form of signage or at visitor information centers. It is a part of welcoming the visitor and assists them in planning their experience. Information After basic orientation, visitors typically seek general information about the area, including the locations of points of interest and other options for how they may choose to spend their time. These locations where the visitor is likely to stop, dictate where and in what form interpretation is appropriate. -

ASTERACEAE Christine Pang, Darla Chenin, and Amber M

Comparative Seed Manual: ASTERACEAE Christine Pang, Darla Chenin, and Amber M. VanDerwarker (Completed, April 17, 2019) This seed manual consists of photos and relevant information on plant species housed in the Integrative Subsistence Laboratory at the Anthropology Department, University of California, Santa Barbara. The impetus for the creation of this manual was to enable UCSB graduate students to have access to comparative materials when making in-field identifications. Most of the plant species included in the manual come from New World locales with an emphasis on Eastern North America, California, Mexico, Central America, and the South American Andes. Published references consulted1: 1998. Moerman, Daniel E. Native American ethnobotany. Vol. 879. Portland, OR: Timber press. 2009. Moerman, Daniel E. Native American medicinal plants: an ethnobotanical dictionary. OR: Timber Press. 2010. Moerman, Daniel E. Native American food plants: an ethnobotanical dictionary. OR: Timber Press. Species included herein: Achillea lanulosa Achillea millefolium Ambrosia chamissonis Ambrosia deltoidea Ambrosia dumosa Ambrosia eriocentra Ambrosia salsola Artemisia californica Artemisia douglasiana Baccharis pilularis Baccharis spp. Bidens aurea Coreopsis lanceolata Helianthus annuus 1 Disclaimer: Information on relevant edible and medicinal uses comes from a variety of sources, both published and internet-based; this manual does NOT recommend using any plants as food or medicine without first consulting a medical professional. Achillea lanulosa Family: Asteraceae Common Names: Yarrow, California Native Yarrow, Common Yarrow, Western Yarrow, Mifoil Habitat and Growth Habit: This plant is distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere. It is native in temperate areas of North America. There are both native and introduced species in areas creating hybrids. Human Uses: This plant has a positive fragrance making it desired in gardens. -

Late Cenozoic Stratigraphy of the Feather and Yuba Rivers Area, California, with a Section on Soil Development in Mixed Alluvium at Honcut Creek

/ ( r- / Late CenozoiC Stratigraphy of the Feather and Yuba Rivers Area, California, with a Section on Soil Development in Mixed Alluvium at Honcut Creek U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1590-G AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL Books OVER THE COUNTER Books . Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. -

Chapter 20-Indian Trust Assets

CHAPTER 20 INDIAN TRUST ASSETS ITAs are legal interests in property held in trust by the United States for federally recognized Indian tribes or individual Indians. An Indian Trust has three components: (1) the trustee; (2) the beneficiary; and (3) the trust asset. ITAs can include land, minerals, federally reserved hunting and fishing rights, federally reserved water rights, and instream flows associated with trust land. Beneficiaries of the Indian Trust relationship are federally recognized Indian tribes with trust land; the United States is the trustee. By definition, ITAs cannot be sold, leased, or otherwise encumbered without approval of the United States. The characterization and application of the United States trust relationship have been defined by case law that interprets Congressional acts, executive orders, and historic treaty provisions. All bureaus are responsible for, among other things, identifying any impact of their plans, projects, programs or activities on ITAs; ensuring that potential impacts are explicitly addressed in planning, decision, and operational documents; and consulting with recognized tribes who may be affected by proposed activities. Consistent with this, Reclamation's Indian Trust policy states that Reclamation will carry out its activities in a manner which protects ITAs and avoids adverse impacts when possible, or provides appropriate mitigation or compensation when it is not. To carry out this policy, Reclamation incorporated procedures into its NEPA compliance procedures to require evaluation of the potential effects of its proposed actions on trust assets (Reclamation 1997). 20.1 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING/AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT Information regarding traditional cultural properties, historic properties, ITAs, and ethnographic resources located in the project area can be used to characterize the prehistoric, ethnographic, and historic cultural resources and ITAs that may be affected by implementation of the Proposed Project/Action and alternatives. -

Section 3 Existing Environment

Yuba County Water Agency Narrows Hydroelectric Project FERC Project No. 1403 SECTION 3 EXISTING ENVIRONMENT In addition to this introductory information, this section is divided into two subsections. Section 3.1 provides a general description of the river basin in which the Project occurs. Section 3.2 provides existing, relevant and reasonably available information regarding the resources. 3.1 General Description of the River Basin 3.1.1 Existing Water Projects in the Yuba River Basin Sixteen existing water projects occur in the Yuba River Basin. Eight of the water projects are licensed or exempt from licensing by FERC. Together, these eight projects have a combined FERC-authorized capacity of 782.1 MW, of which the Narrows Hydroelectric Project has approximately 1.5 percent of the total capacity. The remaining eight non-FERC-licensed projects do not contain generating facilities. Each of these water projects is described briefly below. 3.1.1.1 Narrows Hydroelectric Project The existing Narrows Hydroelectric Project is described in detail in Section 2 of this PAD. 3.1.1.2 Upstream of the Narrows Hydroelectric Project 3.1.1.2.1 South Feather Power Project The 117.5-MW South Feather Power Project, FERC Project No. 2088, is a water supply/power project constructed in the late 1950s/early 1960s and is owned and operated by the South Feather Water and Power Agency (SFWPA). None of the project facilities or features is located in the Yuba River watershed except for the Slate Creek Diversion Dam, which is located on a tributary to the North Yuba River. -

Brown's Island Plants

Brown’s Island Plants A photographic guide to wild plants of Brown’s Island Regional Preserve Sorted by Scientific Name Photographs by Wilde Legard Botanist, East Bay Regional Park District Revision: February 23, 2007 More than 2,000 species of native and naturalized plants grow wild in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most are very difficult to identify without the help of good illustrations. This is designed to be a simple, color photo guide to help you identify some of these plants. The selection of plants displayed in this guide is by no means complete. The intent is to expand the quality and quantity of photos over time. The revision date is shown on the cover and on the header of each photo page. A comprehensive plant list for this area (including the many species not found in this publication) can be downloaded at the East Bay Regional Park District’s wild plant download page at: http://www.ebparks.org. This guide is published electronically in Adobe Acrobat® format to accommodate these planned updates. You have permission to freely download, distribute, and print this pdf for individual use. You are not allowed to sell the electronic or printed versions. In this version of the guide, the included plants are sorted alphabetically by scientific name. Under each photograph are four lines of information, based on upon the current standard wild plant reference for California: The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, 1993. Scientific Name Scientific names revised since 1993 are NOT included in this edition. Common Name These non-standard names are based on Jepson and other local references. -

The Valley Nisenan

W,MO 4R. V Nifv X" T, 4ei WI -N K 7,4 Al Rol P 5", AW wk tx- ".l4Z ,.,A.,Ift A b. lU Tlk wl Z'o "',Ni V- _fYR ..Nk 41 .te f IM 7 x J. x .C- .7 In WW, V, A 7" 4 Zll. 4IN t2 Ph v0:1 VAl"'. PN A '_.,_7, 4A W, "W. ol" IIA M `01C 4- Y'-4!" SI V-4. 'f,:,V.p C uN. A KII V7-1 AVINK "I ZkP`1 -TW 4._ V: 74 tk ll..Il 7N SI, I;p t4. .w -4- WV, pi .MP 41 A % 'W: J 3 N, 2. :1I-. i : ST :or OAWORMiA PLWA;:ATIQ:N .DE., ,-T 1 'O AtTHROPO,O,1 The f6Owig puO 4ealiiig t caogInd oo1 sbcss -nr *idirectionthe of theDatxf etQf oolog ae st In a the- pbl: iations of ls,0d$ for o ldvX gt ral- or- t arcaeo9gky d314 tigy 2 r s ah Is stated' :.opoleyh;ge sdo . be directed .t: I'2*fl E];XQEAG DZARTMENT, UNIVB381, : '1~RART, ' KE CV,'' At 'I;EOCA:.Bi. S. AX Orders 'n& rgttaic shld be. ad4rese d to the UN1VZi*8ITY OP A.O;B ,ORNIA S8;. $-bIctlo31s o thtwoeaUixSveritJio MtoiePrs may1tbe; QbtaIred fromi THB CAM. - :^, PG V3.IXS~~ PEB38, FZEZIW tLANE, LO1NWDON Z.O 4, EXD; to whc ^ ; o/l^erdets oiginating Oreat BritGn edafreland sho'lb;e sent. X3AMt:EIA AZCIHAEQ^O(CY AND HEOG-A i roeber .and Robet . Lie .:03d$rs. Prices,0 Voltut 1, $.5; Volumes -2 :to, 11, incliv, $.