Goals/Objectives/Student Outcomes: Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context, 1837 to 1975

SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota May 2017 SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota MnHPO File No. Pending 106 Group Project No. 2206 SUBMITTED TO: Aurora Saint Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation 774 University Avenue Saint Paul, MN 55104 SUBMITTED BY: 106 Group 1295 Bandana Blvd. #335 Saint Paul, MN 55108 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Nicole Foss, M.A. REPORT AUTHORS: Nicole Foss, M.A. Kelly Wilder, J.D. May 2016 This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context ABSTRACT Saint Paul’s African American community is long established—rooted, yet dynamic. From their beginnings, Blacks in Minnesota have had tremendous impact on the state’s economy, culture, and political development. Although there has been an African American presence in Saint Paul for more than 150 years, adequate research has not been completed to account for and protect sites with significance to the community. One of the objectives outlined in the City of Saint Paul’s 2009 Historic Preservation Plan is the development of historic contexts “for the most threatened resource types and areas,” including immigrant and ethnic communities (City of Saint Paul 2009:12). The primary objective for development of this Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context Project (Context Study) was to lay a solid foundation for identification of key sites of historic significance and advancing preservation of these sites and the community’s stories. -

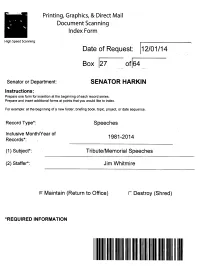

Senator Tom Harkin DT

Printing, Graphics, & Direct Mail Document Scanning Index Form High Speed Scanning Date of Request: 12/01/14 Box 27 of 64 Senator or Department: SENATOR HARKIN Instructions: Prepare one form for insertion at the beginning of each record series. Prepare and insert additional forms at points that you would like to index. For example: at the beginning of a new folder, briefing book, topic, project, or date sequence. Record Type*: Speeches Inclusive Month/Year of Records*: 1981-2014 (1) Subject*: Tribute/Memorial Speeches (2) Staffer*: Jim Whitmire rx Maintain (Return to Office) r Destroy (Shred) *REQUIRED INFORMATION 11111111111111111| II|II Senator Tom Harkin Ft. Des Moines Memorial Park and Education Center January 21, 2002 Thank you, Robert [Morris, Exec. Dir. of the Ft. DSM Memorial Park and Education Center] for that kind introduction. And thank you most of all for bringing the Fort Des Moines Memorial Park and Education Center to life. Robert, Steve Kirk, and the entire board have done yeoman's work in this effort and we owe them a great deal of thanks. I want to thank my colleague and friend Leonard Boswell for joining us. As veterans ourselves, we're here to say thank you for honoring the men and women who prepared for their military service at Fort Des Moines. My thanks as well to Mayor Preston Daniels for his support for this effort and for the vision and leadership he provides Des Moines. It's an honor as well to be here with Reverend Ratliff, President Maxwell of Drake and his wife, Madeline, and David Walker of Drake Law School. -

Eleanor's Story: Growing up and Teaching in Iowa: One African American Woman's Experience Kay Ann Taylor Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2001 Eleanor's story: growing up and teaching in Iowa: one African American woman's experience Kay Ann Taylor Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Educational Sociology Commons, Oral History Commons, Other Education Commons, Other History Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social History Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Kay Ann, "Eleanor's story: growing up and teaching in Iowa: one African American woman's experience " (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 681. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/681 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

From Adolescent Protester to Piano Technician, Nurse and Child Advocate

Children's Legal Rights Journal Volume 39 Issue 2 Article 2 2019 The Transformation of a Shy Girl: From Adolescent Protester to Piano Technician, Nurse and Child Advocate Mary Anderson Richards Follow this and additional works at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/clrj Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Juvenile Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary A. Richards, The Transformation of a Shy Girl: From Adolescent Protester to Piano Technician, Nurse and Child Advocate, 39 CHILD. LEGAL RTS. J. 127 (2020). Available at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/clrj/vol39/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Children's Legal Rights Journal by an authorized editor of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Richards: The Transformation of a Shy Girl: From Adolescent Protester to Pi The Transformation of a Shy Girl: From Adolescent Protestor to Piano Technician, Nurse and Child Advocate Mary Anderson Richards, Ph.D.' It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutionalrights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.2 This shy girl did not know that wearing a black armband to school would forever define her life. Thirteen-year-old Mary Beth Tinker wavered on the idea of wearing a black armband to Warren Harding Junior High School in Des Moines, Iowa on December 16, 1965. But with the media providing graphic visual and audio reports on the United States' involvement in Vietnam, Mary Beth had developed strong feelings on the issue. -

Edna Griffin and the Katz Drug Store Desegregation Movement" Essay from the Annals of Iowa, 2008

“Since it is my right, I would like to have it: Edna Griffin and the Katz Drug Store Desegregation Movement" Essay from The Annals of Iowa, 2008 Since it is my right, I would like to have it: Edna Griffin and the Katz Drug Store Desegregation Movement Noah Lawrence Hinsdale Central High School ON JULY 7, 1948, sometime between 2:30 and 5:00 p.m., Edna Griffin, age 39; her infant daughter, Phyllis; John Bibbs, age 22; and Leonard Hudson, age 32, entered Katz Drug Store at the intersection of 7th and Locust streets in Des Moines. While Hudson went to look for some batteries, Griffin and Bibbs took seats at the lunch counter, and a waitress came shortly to take their order. The two African Americans ordered ice cream sundaes, but as the waitress walked toward the ice cream dispenser, a young white man came and whispered a message into her ear. The waitress returned to Griffin and Bibbs and informed the pair that she was not allowed to serve them, because of their race. By that time Hudson had finished purchasing a set of batteries and rejoined his companions. The three adults asked to see the waitress’s supervisor, and she obliged, summoning the young fountain manager, C. L. Gore, a 22-year-old who had come north from Florida just two years earlier. The tenor of that exchange would later be disputed: Griffin, Bibbs, and Hudson claimed that the conversation was hushed and polite; Gore said that the three black patrons were causing a disturbance. What is not disputed is that Griffin and Hudson were unsuccessful in getting any ice cream that day, despite appealing to store manager Maurice Katz. -

Gov't Wants $45 Billion to Keep Nuclear Arsenal

An interview with THE Marxist editor from Africa Pages 8-10 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 52/NO. 50 DECEMBER 23, 1988 $1.00 Gov't wants $45 billion In switch, U.S. gov't to keep nuclear arsenal will talk The trickle of revelations has become a flood. An environmental disaster, perpe with PLO trated by the U.S. government, is taking place at nuclear weapons production plants BY HARRY RING Washington's decision to negotiate with across the country. the Palestine Liberation Organization rep The 12 plants have poured radioactive resented an abrupt reversal of U.S. policy. and other toxic wastes into the environ- It registers a setback to the Israeli regime and its efforts to smash with an "iron fist" the Palestinian uprising on the West Bank EDITORIAL and in the Gaza Strip. The December 14 announcement by President Ronald Reagan and Secretary of ment. Nuclear accidents, radioactive emis State George Shultz came on the heels of a sions, and toxic dumping have been know press conference hours earlier by PLO ingly concealed from the public. Chairman Yassir Arafat in which he reiter The damage to the health of workers in ated earlier declarations recognizing Israel side the weapons plants has yet to be accu and reaffirming the PLO's opposition to rately gauged and made public. "Many oc terrorism. cupational health professionals say it is im Just 24 hours before the U.S. switch, possible to draw any conclusions about the Arafat had made these same points to the health of the nuclear workers," reported the UN General Assembly and Washington December II New York Times, "because had rebuffed him. -

THE ANNALS of IOWA 67 (Fall 2008)

The Annals of Volume 67, Number 4 Iowa Fall 2008 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue DEREK R. EVERETT offers a full account of the “border war” between Iowa and Missouri from 1839 to 1849, expanding the focus beyond the usual treatment of the laughable events of the “Honey War” in 1839 to illustrate the succession of events that led up to that conflict, its connection to broader movements in regional and national history, and the legal and social consequences of the controversy. Derek R. Everett teaches history at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. NOAH LAWRENCE tells the story of Edna Griffin and her struggle to desegregate the Katz Drug Store in Des Moines in 1948. His account re- veals that Griffin was a radical black activist who was outspoken through- out her life about the need for economic and racial justice, yet her legal strategy during the trial constructed her as a “respectable” middle-class mother rather than as a firebrand activist. Noah Lawrence is a high school history teacher at Hinsdale Central High School in Hinsdale, Illinois. Front Cover Protesters picket outside Katz Drug Store in Des Moines in 1948. Many of the signs connect the struggle for desegregation to the fight against Nazi Germany during World War II. For more on the struggle for desegregation in Des Moines, see Noah Lawrence’s article in this issue. This photograph, submitted as evidence in the Katz trial and folded into the abstract, was provided courtesy of the University of Iowa Law Library, Iowa City. (For a full citation of the abstract, see the first footnote in Lawrence’s article.) Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. -

Rosa Parks: a Life – Study Guide-Part I

Study Guide and Learning Activities for Rosa Parks: A Life by Dr. Douglas Brinkley This study guide has been developed by Judy S. Miller, M.Ed., M.A., Student News Net editor, in support of the April 27, 2018 Student News Net Symposium: Actions and Accomplishments of African American Women of the 1940s and 1950s. Dr. Douglas Brinkley will be the keynote speaker discussing his book, Rosa Parks: A Life, published in 2000. Students are invited to read the book before the Symposium and submit presentations to the Symposium through this website beginning in March. Symposium website: www.studentshareknowledge.com Rosa Parks is fingerprinted during her second arrest on Feb. 22, 1956. (Photo: Library of Congress) Rosa Parks: A Life by Douglas Brinkley Overview Age range: grades 7-12 Part I – Chapters 1 through 9 (pp. 1-173) Part I of the Study Guide covers the life of Rosa Parks through her Dec. 1, 1955 refusal to give up her seat on Montgomery City Bus #2857 and the immediate aftermath of that brave action. For her safety, her brother convinced Rosa and Raymond, her husband, to move to Detroit in 1957 where she lived until her death in 2005. Part II – (Chapters 11-12 on pp. 174-246) Part II of the Study Guide covers the last three chapters in the book from 1957 on after Rosa Parks moved to Detroit. © 2018 Student News Net, Redwood Educational Technologies - 1 - Objectives: After reading Dr. Brinkley's book and completing activities in this study guide, students will be able to: 1. Summarize the reason Dr. -

The Annals of Iowa Volume 69, Number 1

The Annals of Volume 69, Number 1 Iowa Winter 2010 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue WILLIAM C. LOWE, dean and professor of history at Ashford Uni- versity in Clinton, Iowa, recounts the events surrounding the tour taken by Governor Cummins and other Iowa officials to dedicate Iowa’s new Civil War monuments at Andersonville and at the Civil War battlefield parks at Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and Shiloh. He also analyzes how the commemo- rations participated in prevailing ways of remembering the Civil War. BRUCE FEHN AND ROBERT JEFFERSON describe how the Des Moines chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense emerged in 1968 out of African Americans’ efforts to survive and thrive under particular local conditions of racism, discrimination, and segregation. The authors conclude that the Black Panthers gave a radical shove to black politics but also drew on the support of traditional African American leaders and even some sympathetic members of the white community in Des Moines. Front Cover George Landers’s 55th Regimental Band, from Centerville, Iowa, poses in front of the Rossville Gap monument during the Civil War monument tour in 1906. (The drum logo still carried the band’s older designation as the 51st Regiment band. Iowa’s National Guard regiments were renumbered after federal service in the Spanish-American War, and the 51st became the 55th.) Landers is seated in the front row, fourth from the left (without in- strument). For more on the Civil War monument tour in 1906, see William Lowe’s article in this issue. Photo from State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines. -

African American Officers of World War I in the Battle for Racial Equality

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Deeds, Not Words: African American Officers oforld W War I in the Battle for Racial Equality Adam Patrick Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Adam Patrick, "Deeds, Not Words: African American Officers oforld W War I in the Battle for Racial Equality" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 314. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/314 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “DEEDS, NOT WORDS:” AFRICAN AMERICAN OFFICERS OF WORLD WAR I IN THE BATTLE FOR RACIAL EQUALITY A Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in the Department of History The University of Mississippi By ADAM PATRICK WILSON April 2012 Copyright Adam Patrick Wilson ALL RIGHTS RESERVE ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the relatively untold story of the black officers of the Seventeenth Provisional Training Regiment, the first class of African Americans to receive officer training. In particular, this research examines the creation of the segregated Army officer training camp, these men’s training and wartime experiences during World War I, and their post- war contributions fighting discrimination and injustice. These officers returned to America disillusioned with the nation’s progress towards civil rights. Their leadership roles in the military translated into leadership roles in the post-war civil rights movement. -

Page | 1 Iowa Civil Rights Commission Grimes State Office

Iowa Civil Rights Toolkit Iowa Civil Rights Commission Grimes State Office Building 400 E. 14th Street Des Moines, IA 50319-0201 515-281-4121, 1-800-457-4416 Fax 515-242-5840 https://icrc.iowa.gov Page | 1 Iowa Civil Rights Toolkit Table of Contents (Note: you may click on the title or page number to jump to that section) Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 The Iowa Civil Rights Act and other Legislation ..................................................................... 5 Civil Rights vs. Civil Liberties: What’s the Difference? .......................................................... 7 Iowa Civil Rights Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8 Racial Equality .............................................................................................................................. 12 In the Matter of Ralph (1839) ................................................................................................. 12 Rachel, a Negro Woman, v. James Cameron, Sheriff (1839) ................................................. 15 Clark v. Board of Directors (1868) ......................................................................................... 16 Alexander Clark ...................................................................................................................... 17 Coger v. The Northwestern Union Packet Co. (1873) ...........................................................