Page | 1 Iowa Civil Rights Commission Grimes State Office

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rmte6 MAY 16 1978

THERMAL DELIGHT IN ARCHITECTURE by Lisa Heschong B.Sc., University of California at Berkeley 1973 submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1978 Signature of Author ............. Department of Architecture Februa. 14, 978 Certified by......................................................... Edward B. Allen, Thesis Supervisor Associate Professor of Architecture Accepted by...0. ..... ... Ch ter Sprague, Chairman Departmental Committee for Graduate Students Copyright 1978, Lisa Heschong RMte6 MAY 16 1978 Abstract THERMAL DELIGHT IN ARCHITECTURE Lisa Heschong Submitted to the Department of Architecture on February 14, 1978 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture. This thesis examines the broad range of influences that thermal qualities have on architectural space and peoples' response to it. It begins with the observation that proper thermal conditions are necessary for all life forms, and examines the various strategies used by plants and animals to survive in spite of adverse thermal conditions. Human beings have available to them the widest range of thermal strategies. These include the skillful use of building technologies to create favorable microclimates, and the use of ar- tificial power to maintain a comfortable thermal environment. Survival strategies and the provision of thermal comfort are only the most basic levels of our relationship to the thermal en- vironment. Our experience of the world is through our senses, in- cluding the thermal sense. Many examples demonstrate the relation- ship of the thermal sense to the other senses. The more sensory input we experience, and the more varied the contrasts, the richer is the experience and its associated feelings of delight. -

Iowa Women's History Quiz: Test Your Knowledge of Iowa's Female Leaders Iowa Commission on the Status of Women

Iowa Women's History Quiz: Test Your Knowledge of Iowa's Female Leaders Iowa Commission on the Status of Women 1. Who was the first woman attorney in the United States? (Hint: She was a native Iowan and passed the bar examination in Henry County in 1869.) 2. Two leaders of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the latter half of the 1880s came from Iowa. Can you name them? (Hint: One gave her name to a type of undergarment worn by women…the other succeeded Susan B. Anthony as president of the National Woman Suffrage Association.) 3. What woman founded the Iowa Highway Patrol? (Hint: She was also Iowa's first female Secretary of State.) 4. Who was the first woman elected to statewide office in Iowa? (Hint: She was elected Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1922.) 5. Who was the first woman to serve in the Iowa House of Representatives? (Hint: She was first elected in 1928. She also went on to become the first woman elected to the Iowa Senate.) 6. Who was the first woman appointed as a Superintendent of a City School District in the United States? (Hint: She was appointed superintendent of schools in Davenport in 1874. Naturally, she had to fight to receive the same salary the school district had to pay men. She won!) 7. Who was the first woman elected Lieutenant Governor of Iowa? (Hint: It was before Joy Corning.) 8. Who was the first woman appointed to serve on the Iowa Supreme Court? (Hint: She was appointed in 1986.) 9. -

Iowa Commission on the Status of Women State of Iowa Department of Human Rights

Iowa Commission on the Status of Women State of Iowa Department of Human Rights 34th Annual Report February 1, 2006 Lucas State Office Building Des Moines, IA 50319 Tel: 515/281-4461, 800/558-4427 Fax: 515/242-6119 [email protected] www.state.ia.us/dhr/sw Thomas J. Vilsack, Governor y Sally J. Pederson, Lt. Governor Charlotte Nelson, Executive Director Lucas State Office Building y Des Moines, Iowa 50319 Telephone: (515) 281-4461, (800) 558-4427 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.state.ia.us/dhr/sw IOWA Fax: (515) 242-6119 COMMISSION ON THE February 1, 2006 STATUS OF WOMEN The Honorable Thomas J. Vilsack The Honorable Sally J. Pederson Members of the 81st General Assembly State Capitol Building Des Moines, IA 50319 Dear Governor Vilsack, Lieutenant Governor Pederson, and Members of the 81st General Assembly: At the end of every year, the Iowa Commission on the Status of Women (ICSW) reviews its accomplishments. The ICSW is proud of the past year’s achievements, and pleased to present to you our 34thAnnual Report. The following pages detail the activities and programs that were carried out in 2005. The ICSW celebrates the progress in women’s rights that has been made in Iowa, and continues to address inequities, advocating for full participation by women in the economic, social, and political life of the state. In this advocacy role, as mandated by the Code of Iowa, we educate, inform, and develop new ideas to bring a fresh viewpoint to bear on the issues facing Iowa women and their families. -

Bosnian Muslim Reformists Between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1901-1914 Harun Buljina

Empire, Nation, and the Islamic World: Bosnian Muslim Reformists between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1901-1914 Harun Buljina Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Harun Buljina All rights reserved ABSTRACT Empire, Nation, and the Islamic World: Bosnian Muslim Reformists between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1901-1914 Harun Buljina This dissertation is a study of the early 20th-century Pan-Islamist reform movement in Bosnia-Herzegovina, tracing its origins and trans-imperial development with a focus on the years 1901-1914. Its central figure is the theologian and print entrepreneur Mehmed Džemaludin Čaušević (1870-1938), who returned to his Austro-Hungarian-occupied home province from extended studies in the Ottoman lands at the start of this period with an ambitious agenda of communal reform. Čaušević’s project centered on tying his native land and its Muslim inhabitants to the wider “Islamic World”—a novel geo-cultural construct he portrayed as a viable model for communal modernization. Over the subsequent decade, he and his followers founded a printing press, standardized the writing of Bosnian in a modified Arabic script, organized the country’s Ulema, and linked these initiatives together in a string of successful Arabic-script, Ulema-led, and theologically modernist print publications. By 1914, Čaušević’s supporters even brought him to a position of institutional power as Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Reis-ul-Ulema (A: raʾīs al-ʿulamāʾ), the country’s highest Islamic religious authority and a figure of regional influence between two empires. -

Iowa's Role in the Suffrage Movement

Lesson #5 Commemorating the Centennial Of the 19th Amendment Designed for Grades 9-12 6 Lesson Unit/Each Lesson 2 Days Based on Iowa Social Studies Standards Iowa’s Role in the Suffrage Movement Unit Question: What is the 19th Amendment, and how has it influenced the United States? Supporting Question: How was Iowa involved in the promotion of and passage of the 19th Amendment? Lesson Overview The lesson will highlight suffrage leaders with Iowa ties and events in the state leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment. Lesson Objectives and Targets Students will… 1. take note of key events in Iowa’s path to achieve women’s enfranchisement. 2. read provided biographical entries on selected Iowa suffrage leaders. 3. read and review the University of Iowa Library Archives selections on suffrage, selections from the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics website, and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame coverage about Iowa suffragists and contemporary Iowa women leaders.. Useful Terms and Background ● Iowa Organizations - Iowa Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), Iowa Equal Suffrage Association (IESA) along with several local and state clubs of support ● National suffrage leaders with Iowa roots - Amelia Jenks Bloomer & Carrie Chapman Catt ● Noted Iowa suffragists included in the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame ● Suffrage activities throughout the state ● Early state attempts for amendments along with Iowa ratification of the 19th Amendment Lesson Procedure Day 1 Teacher Notes for Day 1 1. Point out that lesson materials have been selected from three unique Iowa sources: the University of Iowa Library Archives and the websites for Iowa State University’s Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. -

Other Social Effects Report

OTHER SOCIAL EFFECTS REPORT City of Cedar Rapids, Iowa - Flood of 2008 Created on June 7, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Abbe Center for Mental Health Cedar Rapids Community School District Cedar Rapids Area Chamber of Commerce Corridor Recovery Cedar Rapids Downtown District City of Cedar Rapids Departments - Community Development - Public Works - Utilities (Water Department and Water Pollution Control) - Parks and Recreation - Finance - Police Department - Fire Department - Code Enforcement - CR Transit - City Manager‘s Office Dennis P. Robinson Gerry Galloway JMS Communications & Research Linn County Long Term Recovery Coalition Ken Potter, Professor of Civil & Environmental Engineering, University of Wisconsin Red Cross Salvation Army Sasaki Associates The Greater Cedar Rapids Community Foundation United States Army Corps of Engineers, Rock Island District Other Social Effects Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 Overview ................................................................................................................................. 4 Scope of Report....................................................................................................................... 6 Key Messages ........................................................................................................................ -

2018 Updated

Media Guide 2003 (PAGES 138-151 in 2018 GUIDE) EDMONTON ESKIMO INDIVIDUAL RECORDS REGULAR SEASON (RECORDS FOR MODERN ERA, SINCE 1949) GAMES PLAYED MOST GAMES PLAYED CAREER 274 Rod Connop 268 Sean Fleming 254 Dave Cutler 237 Chris Morris 217 Blake Dermott 213 Larry Wruck 200 Henry Williams 192 Hector Pothier 191 Bill Stevenson 185 Leroy Blugh POINTS MOST POINTS CAREER 2571 Sean Fleming 2237 Dave Cutler 677 Jack Parker 586 Brian Kelly 577 Jerry Kauric 430 Normie Kwong 430 Grant Shaw 426 Jim Germany 423 Grant Shaw 412 Johnny Bright MOST POINTS SEASON 224 Kauric 1989 207 Fleming 1995 204 Fleming 1994 195 Cutler 1977 190 Dixon 1986 187 Fleming 1997 186 Macoritti 1990 185 Fleming 2000 183 Fleming 2001 182 Whyte 2016 MOST POINTS GAME 30 Blount Wpg at Edm Sept. 15, 1995 24 Germany Ham at Edm Aug. 1, 1981 24 Kelly Ott at Edm June 30, 1984 24 Fleming Edm at BC Oct. 29, 1993 24 McCorvey Wpg at Edm July 21, 2000 22 Jack Parker BC at Edm Sept. 21, 1959 21 Kauric Edm at Sask Aug. 30, 1989 Records-Individual Edmonton Eskimo Football Club Media Guide 2003 (PAGES 138-151 in 2018 GUIDE) EDMONTON ESKIMO INDIVIDUAL RECORDS REGULAR SEASON (RECORDS FOR MODERN ERA, SINCE 1949) 20 Cutler Sask at Edm Aug. 30, 1981 20 Kauric BC at Edm July 13, 1989 20 Macoritti Edm at Ham Aug. 10, 1991 20 Fleming Edm at Sac Aug. 18, 1994 20 Fleming Edm at BC Oct. 12, 1996 20 Fleming Mtl at Edm July 17, 1997 20 Fleming Mtl at Edm July 17, 1997 Records-Individual Edmonton Eskimo Football Club Media Guide 2003 (PAGES 138-151 in 2018 GUIDE) EDMONTON ESKIMO INDIVIDUAL RECORDS REGULAR SEASON (RECORDS FOR MODERN ERA, SINCE 1949) TOUCHDOWNS MOST TOUCHDOWNS CAREER 97 Brian Kelly 79 Jack Parker 77 Normie Kwong 71 Jim Germany 69 Johnny Bright 65 Blake Marshall 59 Jason Tucker 58 Tom Scott 53 Henry Williams 51 Jim Thomas 51 Waddell Smith MOST TOUCHDOWNS SEASON 20 B. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

Tenseniorstobowoutsaturday in Classic Battle With

E3fl Is' N«w Bandma.t.r dham's nd Plans to *» d Al McNqmora Giv« Viawt ns On The New Monthly's Top* •« City— N«w Look- Pag* 3 FORDHAM COLLEGE, NEW~YORK, NOVEMBER 21, 1951 Defense: Fordham's Unit Stars in Drill TenSeniorstoBowOutSaturday As dozens of sirens in the New York area sprung into action and sound- • Bir warning of the practice air raid Wednesday evening Nov. 14, Ford- In Classic Battle with NYU University's Civil Defense Mobile First Aid Unit was stationed at post at Fordham Hospital, waiting to be called into action. By MM JACOBY In the Fordham unit, there were 184 personnel, consisting entirely of In the twenty-ninth renewal of the Fordham-NYU grid rivalry, ten •dents and faculty members of the® TELECAST FROM CHURCH Maroon Seniors will ring down the curtain on their college football armacy School. The unit was or The Fordham University Church careers this Saturday at Randall's Island. Taking the field for the last nized and under the direction o: will be the scene of a series of time will be such defensive stalwarts as end and Captain Chris Campbell, Leonard J. Piccoli, Professor o StudentsConfer nation-wide telecasts over the tackle Art Hickey, end Tom Bourke, halfback Bill Sullivan, end Dick lic Health of the Fordham Col- National Broadcasting Company fMotta, and guard Bill Snyder. The e of Pharmacy. The Medical Di during the month of'December. offensive stars who will bid adieu tor of the aid station is Dr. Josep! With Faculty The NBC television series, include Ed Kozdeba, extra-point s and the Chaplain is Rev. -

Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context, 1837 to 1975

SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota May 2017 SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota MnHPO File No. Pending 106 Group Project No. 2206 SUBMITTED TO: Aurora Saint Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation 774 University Avenue Saint Paul, MN 55104 SUBMITTED BY: 106 Group 1295 Bandana Blvd. #335 Saint Paul, MN 55108 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Nicole Foss, M.A. REPORT AUTHORS: Nicole Foss, M.A. Kelly Wilder, J.D. May 2016 This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context ABSTRACT Saint Paul’s African American community is long established—rooted, yet dynamic. From their beginnings, Blacks in Minnesota have had tremendous impact on the state’s economy, culture, and political development. Although there has been an African American presence in Saint Paul for more than 150 years, adequate research has not been completed to account for and protect sites with significance to the community. One of the objectives outlined in the City of Saint Paul’s 2009 Historic Preservation Plan is the development of historic contexts “for the most threatened resource types and areas,” including immigrant and ethnic communities (City of Saint Paul 2009:12). The primary objective for development of this Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context Project (Context Study) was to lay a solid foundation for identification of key sites of historic significance and advancing preservation of these sites and the community’s stories. -

The Blue Book of Iowa Women

REYNOLD?^ WicjoRic/s^L GENEALOGY COLLECTION ^s.oia^Boo,?«T&^^,, 'i^'')>< 'S/;SV 1G6715G To your mother, and to my own of blessed memory, to whom we owe all that we are and to whose inspiration we are indebted for all we have tried to do, this book is dedicated. Press of the Missouri Printing and Publishing Company, Mexico. Mo. PREFACE STATE in the union has produced a bet- ter or a higher type of womanhood than Iowa. From pioneer days until the pres- ent they have had a very helpful interest in the advancement of education, of the arts, of literature, of religious and moral training, in the great work of philanthropy and of social service in all of its phases. Some of them have been women of unusual talent and have a national reputation, and some have a world-wide reputation. To record the achievements of these exceptional women, and to make a permanent record of the lives and work of the women who within the State and in their own commu- nities have given their service to the common good is the object of this book. It is not claimed that all the women deserving recognition are included in these pages, no book would be large enough to contain them all. The labor involved in collecting and compiling this history has been far beyond our expectation, yet if we have added to the written history of our state, or if the lives herein recorded prove an inspiration to others, it will be compensation for all the labor it has cost. -

Senator Tom Harkin DT

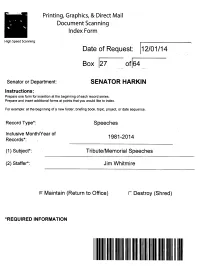

Printing, Graphics, & Direct Mail Document Scanning Index Form High Speed Scanning Date of Request: 12/01/14 Box 27 of 64 Senator or Department: SENATOR HARKIN Instructions: Prepare one form for insertion at the beginning of each record series. Prepare and insert additional forms at points that you would like to index. For example: at the beginning of a new folder, briefing book, topic, project, or date sequence. Record Type*: Speeches Inclusive Month/Year of Records*: 1981-2014 (1) Subject*: Tribute/Memorial Speeches (2) Staffer*: Jim Whitmire rx Maintain (Return to Office) r Destroy (Shred) *REQUIRED INFORMATION 11111111111111111| II|II Senator Tom Harkin Ft. Des Moines Memorial Park and Education Center January 21, 2002 Thank you, Robert [Morris, Exec. Dir. of the Ft. DSM Memorial Park and Education Center] for that kind introduction. And thank you most of all for bringing the Fort Des Moines Memorial Park and Education Center to life. Robert, Steve Kirk, and the entire board have done yeoman's work in this effort and we owe them a great deal of thanks. I want to thank my colleague and friend Leonard Boswell for joining us. As veterans ourselves, we're here to say thank you for honoring the men and women who prepared for their military service at Fort Des Moines. My thanks as well to Mayor Preston Daniels for his support for this effort and for the vision and leadership he provides Des Moines. It's an honor as well to be here with Reverend Ratliff, President Maxwell of Drake and his wife, Madeline, and David Walker of Drake Law School.