THE ANNALS of IOWA 67 (Fall 2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Thoreau’S Journal for 1837 (Æt

HDT WHAT? INDEX 1838 1838 EVENTS OF 1837 General Events of 1838 SPRING JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH SUMMER APRIL MAY JUNE FALL JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER WINTER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER Following the death of Jesus Christ there was a period of readjustment that lasted for approximately one million years. –Kurt Vonnegut, THE SIRENS OF TITAN 1838 January February March Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 1 2 3 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 April May June Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 EVENTS OF 1839 HDT WHAT? INDEX 1838 1838 July August September Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 1 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 October November December Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 1 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Read Henry Thoreau’s Journal for 1837 (æt. -

An Early Opinion of an Arkansas Trial Court

University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review Volume 5 Issue 3 Article 3 1982 An Early Opinion of an Arkansas Trial Court Morris S. Arnold Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview Part of the Courts Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Morris S. Arnold, An Early Opinion of an Arkansas Trial Court, 5 U. ARK. LITTLE ROCK L. REV. 397 (1982). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol5/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review by an authorized editor of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EARLY OPINION OF AN ARKANSAS TRIAL COURT Morris S. Arnold* The opinion printed below merits notice because it is appar- ently the oldest surviving opinion of an Arkansas trial judge.' It was delivered in 1824 in a suit in equity, evidently an accounting between partners, which was brought by James Hamilton against William Montgomery in 1823. Relatively little can be discovered about the plaintiff James Hamilton. He was a merchant in Arkansas Post at least as early as November of 1821 when he moved into the "[s]tore lately occupied by Messrs. Johnston [and] Armstrong."2 Montgomery, on the other hand, is quite a well-known character. From 1819 until 1821 he op- erated a tavern at the Post which was an important gathering place:' A muster of the territorial militia was held there on November 25, 1820,4 and the village trustees were elected there in January of the following year.' Moreover, the first regular legislative assembly for the Territory of Arkansas met in February of 1820 in two rooms furnished by Montgomery, perhaps at his tavern. -

The Iowa Bystander

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1983 The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years Sally Steves Cotten Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cotten, Sally Steves, "The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years" (1983). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16720. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Iowa Bystander: A history of the first 25 years by Sally Steves Cotten A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1983 Copyright © Sally Steves Cotten, 1983 All rights reserved 144841,6 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iii I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE EARLY YEARS 13 III. PULLING OURSELVES UP 49 IV. PREJUDICE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA 93 V. FIGHTING FOR DEMOCRACY 123 VI. CONCLUSION 164 VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 175 VIII. APPENDIX A STORY AND FEATURE ILLUSTRATIONS 180 1894-1899 IX. APPENDIX B ADVERTISING 1894-1899 182 X. APPENDIX C POLITICAL CARTOONS AND LOGOS 1894-1899 184 XI. -

Iowa Hawkeyes to Host National Championship Dual Series

Iowa Hawkeyes to Host National Championship Dual Series Iowa to face an undetermined conference champion Feb. 22 at Carver-Hawkeye Arena IOWA CITY, Iowa -- The University of Iowa has been selected as one of eight host sites for the 2016 NWCA Division I National Championships Dual Series. The second-ranked Hawkeyes will host an undetermined conference champion on Monday, Feb. 22 at 7 p.m. (CT) at Carver-Hawkeye Arena. Iowa’s opponent will be announced Sunday, Feb. 14. Tickets are $15 for adults, $10 for youth, and available for purchase at the UI Athletics Tickets Office, over the phone at 1-800-IA-HAWKS, or online at hawkeyesports.com. Formerly the NWCA National Duals Tournament, the National Championships Dual Series is a new format designed to match the top eight Big Ten programs against the regular season champion from the other seven Division I conferences -- Pac 12, Big 12, ACC, EIAW, EWL, MAC, SoCon, Ivy League. The eighth nonconference team will be selected as an at-large based on its national ranking. The eight Big Ten host schools include No. 1 Penn State, No. 2 Iowa, No. 9 Michigan, No. 10 Ohio State, No. 11 Nebraska, No. 14 Rutgers, No. 18 Minnesota, and Indiana. “The concept is similar to the bowl game series in football,” NWCA President Mark Cody said. “This format was developed by the Division I wrestling coaches and the NWCA’s role is to ensure that it gets off the ground. Our goal is to have the top eight ranked Big Ten schools host a non-Big Ten opponent with one of the duals determining the national dual meet title.” “I’ve been thrilled with the extraordinary level of support this event has received from all participating coaches and administrations,” said NWCA Executive Director Mike Moyer. -

A Timeline of Iowa History

The Beginnings The Geology c. 2.5 billion years ago: Pre-Cambrian igneous and metamorphic c. 1,000 years ago: Mill Creek culture inhabits northwestern Iowa. bedrock, such as Sioux Quartzite, forms in the area that is now Iowa. c. 1,000 years ago: Nebraskan Glenwood culture inhabits c. 500 million years ago: A warm, shallow sea covers the area that is southwestern Iowa. now Iowa. c. 900 years ago: Oneota culture inhabits Iowa for several centuries. c. 500 million years ago: Sedimentary rock begins to form, including The Arrival of the Europeans limestone, sandstone, dolomite, and shale. 1673: Louis Jolliet and Pere Jacques Marquette are the first known c. 500 million years ago: Cambrian rock forms. c. 475 million years Europeans to discover the land that will become Iowa. ago: Ordovician rock forms. c. 425 million years ago: Silurian rock 1682: Rene Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle claims the land in the forms. c. 375 million years ago: Devonian rock forms. Mississippi River valley, including Iowa, for the King of France. c. 350 million years ago: Mississippian rock forms. c. 300 million 1762: Claims to the land that will become Iowa transferred to the King years ago: Pennsylvanian rock forms. c. 160 million years go: of Spain. Jurassic rock forms. c. 75 million years ago: Cretaceous rock forms. 1788: Julien Dubuque creates first European settlement in Iowa. c. 3 million years ago: Glaciers form during a cooling of the earth's surface, and the ice sheets gradually, in several phases, move over 1799: Louis Honore Tesson receives a land grant from the Spanish the area that is now Iowa. -

3. Status of Delegates and Resident Commis

Ch. 7 § 2 DESCHLER’S PRECEDENTS § 2.24 The Senate may, by reiterated that request for the du- unanimous consent, ex- ration of the 85th Congress. change the committee senior- It was so ordered by the Senate. ity of two Senators pursuant to a request by one of them. On Feb. 23, 1955,(6) Senator § 3. Status of Delegates Styles Bridges, of New Hamp- and Resident Commis- shire, asked and obtained unani- sioner mous consent that his position as ranking minority member of the Delegates and Resident Com- Senate Armed Services Committee missioners are those statutory of- be exchanged for that of Senator Everett Saltonstall, of Massachu- ficers who represent in the House setts, the next ranking minority the constituencies of territories member of that committee, for the and properties owned by the duration of the 84th Congress, United States but not admitted to with the understanding that that statehood.(9) Although the persons arrangement was temporary in holding those offices have many of nature, and that at the expiration of the 84th Congress he would re- 9. For general discussion of the status sume his seniority rights.(7) of Delegates, see 1 Hinds’ Precedents In the succeeding Congress, on §§ 400, 421, 473; 6 Cannon’s Prece- Jan. 22, 1957,(8) Senator Bridges dents §§ 240, 243. In early Congresses, Delegates when Senator Edwin F. Ladd (N.D.) were construed only as business was not designated to the chairman- agents of chattels belonging to the ship of the Committee on Public United States, without policymaking Lands and Surveys, to which he had power (1 Hinds’ Precedents § 473), seniority under the traditional prac- and the statutes providing for Dele- tice. -

The Civil War & the Northern Plains: a Sesquicentennial Observance

Papers of the Forty-Third Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains “The Civil War & The Northern Plains: A Sesquicentennial Observance” Augustana College Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 29-30, 2011 Complied by Kristi Thomas and Harry F. Thompson Major funding for the Forty-Third Annual Dakota Conference was provided by Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF, Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission, Tony and Anne Haga, Carol Rae Hansen, Andrew Gilmour and Grace Hansen-Gilmour, Carol M. Mashek, Elaine Nelson McIntosh, Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana College, Rex Myers and Susan Richards, Rollyn H. Samp in Honor of Ardyce Samp, Roger and Shirley Schuller in Honor of Matthew Schuller, Jerry and Gail Simmons, Robert and Sharon Steensma, Blair and Linda Tremere, Richard and Michelle Van Demark, Jamie and Penny Volin, and the Center for Western Studies. The Center for Western Studies Augustana College 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................................................................... v Anderberg, Kat Sailing Across a Sea of Grass: Ecological Restoration and Conservation on the Great Plains ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Anderson, Grant Sons of Dixie Defend Dakota .......................................................................................................... 13 Benson, Bob The -

Scanned Document

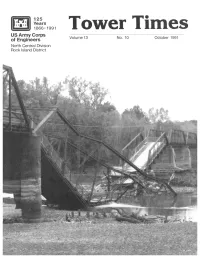

125 Years m 1866-1991 Tower Times US Army Corps of Engineers Volume 13 No. 10 October 1991 North Central Division Rock Island District Col. John R. Brown Commander's Corner To talk of many things ... Congratulations and appreciation for through donations to the charity of our Rock Island District's 125 years of service choice. You should be contacted by a were expressed by the Quad Cities Council keyperson who will provide you all the in of the Chambers of Commerce with a din formation needed to make a decision. If ner and program on the 4th of September. you choose to donate, you can specify the Speakers were Congressman Leach of agency( s) who will benefit from your gift. Iowa, Mayor Schwiebert of Rock Island, As a group, we have been generous in the Commissioner Winborn of Scott County, past and I expect that trend will continue and Mr. Charles Ruhl of the Council of so I thank you for your generosity in ad Chambers of Commerce. It was a pleasant vance. evening on the banks of the Mississippi Safety is still a concern for all of us. We near the Visitors Center with a large tur are making progress in reducing both the nout of guests and our people. I was very rate and severity of the accidents ex proud to accept the speakers' laudatory perienced. However, the rate is not zero so comments on behalf of all the past and we can still improve. I encourage present members of the Rock Island Dis everybody to review their work habits from trict. -

The Honey War by Cassie Dinges

Dinges 1 The Honey War by Cassie Dinges Cassie Dinges is currently a junior at William Jewell College. Next year, she plans to graduate with a degree in both English and Psychology. Cassie has a passion for journalism, and is on the editorial staff of the College’s newspaper, the Hilltop Monitor . In her spare time, she helps with the Lion and Unicorn Reading Program in Liberty, reads, and questions the grammar of others. After graduation, her largest aspiration is to move to New York City to pursue a graduate degree in English, as well as procure an editing position at a publishing house. The concept of a border war is not new to many, especially residents of the Midwest region. Many Missourian children are brought up with tales of civil war scuffles between their state’s Bushwhackers and the Kansan Jayhawkers. The nation still has reminders of these guerilla warfare showdowns today in the form of museums and the mascot of Kansas University. While the border war between Missouri and Kansas is still alive and well known, few know that the Show-Me State almost declared war with the fledgling territory of Iowa. Thirteen miles of land into modern-day Southern Iowa, as well as many profitable honeybee trees became the fodder for a border battle in 1839. This dispute is nicknamed “The Honey War” and was not dismissed after months of bloodshed but rather by a ruling of the Supreme Court. The trouble between Missouri and Iowa can be traced back to the vague state boundaries established for the former when it gained its statehood in 1821. -

Missouri 1861.Pdf

U.S. Army Military History Institute Civil War-Battles-1861 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 31 Mar 2012 MISSOURI OPERATIONS, 1861 A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS General Histories…..p.1 Specific Battles -St. Louis Arsenal (10 May)…..p.3 -Boonville (17 Jun)…..p.4 -Carthage (15 Jul)…..p.4 -Athens (5 Aug)…..p.4 -Wilson's Creek (10 Aug)…..p.5 -Lexington (12-20 Sep)…..p.6 -Springfield (25 Oct)…..p.7 -Belmont (7 Nov)…..p.7 GENERAL HISTORIES Adamson, Hans C. Rebellion in Missouri, l86l: Nathaniel Lyon and his Army of the West. Phila: Chilton, 1961. 305 p. E517.A2. Anderson, Galusha. The Story of a Border City during the Civil War. [St. Louis] Boston: Little, Brown, 1908. 385 p. E517.A54. Barlow, William P. "Remembering the Missouri Campaign of 1861: The Memoirs of Lieutenant... Guibor's Battery, Missouri State Guard." [Edited by Jeffrey L. Patrick] Civil War Regiments Vol. 5, No. 4: pp. 20-60. Per. Bartels, Carolyn. The Civil War in Missouri, Day by Day, 1861 to 1865. Shawnee Mission, KS: Two Trails, 1992. 175 p. E517.B37. Bishop, Albert W. Loyalty on the Frontier, Or Sketches of Union Men of the Southwest: With Incidents and Adventures in Rebellion on the Border. St. Louis, MO: Studley, 1863. 228 p. E496.B61. Broadhead, James O. "Early Events of the War in Missouri." In War Papers (MOLLUS, MO). St. Louis, MO: Becktold, 1892. pp. 1-28. E464.M5.1991v14. Missouri, 1861 p.2 Brugioni, Dino A. The Civil War in Missouri: As Seen from the Capital City. -

Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context, 1837 to 1975

SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota May 2017 SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota MnHPO File No. Pending 106 Group Project No. 2206 SUBMITTED TO: Aurora Saint Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation 774 University Avenue Saint Paul, MN 55104 SUBMITTED BY: 106 Group 1295 Bandana Blvd. #335 Saint Paul, MN 55108 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Nicole Foss, M.A. REPORT AUTHORS: Nicole Foss, M.A. Kelly Wilder, J.D. May 2016 This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context ABSTRACT Saint Paul’s African American community is long established—rooted, yet dynamic. From their beginnings, Blacks in Minnesota have had tremendous impact on the state’s economy, culture, and political development. Although there has been an African American presence in Saint Paul for more than 150 years, adequate research has not been completed to account for and protect sites with significance to the community. One of the objectives outlined in the City of Saint Paul’s 2009 Historic Preservation Plan is the development of historic contexts “for the most threatened resource types and areas,” including immigrant and ethnic communities (City of Saint Paul 2009:12). The primary objective for development of this Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context Project (Context Study) was to lay a solid foundation for identification of key sites of historic significance and advancing preservation of these sites and the community’s stories. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Map of the Des Moines Rapids of the Mississippi River. Drawn by Lt. M.C. Meigs & Henry Kayser Stock#: 53313 Map Maker: Lee Date: 1837 Place: Washington, DC Color: Uncolored Condition: VG+ Size: 21 x 50 inches Price: $ 345.00 Description: Fort Des Moines, Wisconsin Territory Finely detailed map of the section of the Mississippi River, showing the Des Moines Rapids in the area of Fort Des Moines, based upon the surveys of Lieutenant Robert E. Lee of the US Corps of Engineers. The Des Moines Rapids was one of two major rapids on the Mississippi River that limited Steamboat traffic on the river through the early 19th century. The Rapids between Nauvoo, Illinois and Keokuk, Iowa- Hamilton, Illinois is one of two major rapids on the Mississippi River that limited Steamboat traffic on the river through the early 19th century. The rapids just above the confluence of the Des Moines River were to contribute to the Honey War in the 1830s between Missouri and Iowa over the Sullivan Line that separates the two states. The map shows the area between Montrose, Iowa and Nauvoo, Illinois in the north to Keokuk, Iowa and Hamilton, Illinois. On the west bank of the river, the names, Buttz, Wigwam, McBride, Price, Dillon, Withrow, Taylor, Burtis and Store appear. On the east bank, Moffat, Geo. Middleton, Dr. Allen, Grist Mill, Waggoner, Cochran, Horse Mill, Store, Mr. Phelt, and Mrs. Gray, the latter grouped around the town of Montebello.