The Implementation of the Pan-Indian Form on the Keralan Ground. A. R. Rajaraja Varma’S Citranakṣatramālā *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

MA English Revised (2016 Admission)

KANNUR Li N I \/EttSIl Y (Abstract) M A Programme in English Language programnre & Lirerature undcr Credit Based semester s!.stem in affiliated colieges Revised pattern Scheme. s,'rabus and of euestion papers -rmplemenred rvith effect from 2016 admission- Orders issued. ACADEMIC C SECTION UO.No.Acad Ci. til4t 20tl Civil Srarion P.O, Dared,l5 -07-20t6. Read : l. U.O.No.Acad/Ct/ u 2. U.C of €ven No dated 20.1O.2074 3. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pc) held on 06_05_2016. 4. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pG) held on 17_06_2016. 5. Letter dated 27.06.201-6 from the Chairman, Board of Studies in English(pc) ORDER I. The Regulations lor p.G programmes under Credit Based Semester Systeln were implernented in the University with eriect from 20r4 admission vide paper read (r) above dated 1203 2014 & certain modifications were effected ro rhe same dated 05.12.2015 & 22.02.2016 respectively. 2. As per paper read (2) above, rhe Scherne Sylrabus patern - & ofquesrion papers rbr 1,r A Programme in English Language and Literature uncler Credir Based Semester System in affiliated Colleges were implcmented in the University u,.e.i 2014 admission. 3. The meeting of the Board of Studies in En8lish(pc) held on 06-05_2016 , as per paper read (3) above, decided to revise the sylrabus programme for M A in Engrish Language and Literature rve'f 2016 admission & as per paper read (4) above the tsoard of Studies finarized and recommended the scheme, sy abus and pattem of question papers ror M A programme in Engrish Language and riterature for imprementation wirh efl'ect from 20r6 admissiorr. -

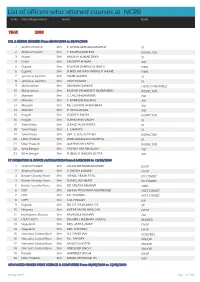

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Amrita Kiranam November 2017

Deemed-to-be-University u/s 3 of UGC Act 1956 No. 12 | Vol. 14 | November 2017 a snapshot and journal of happenings @ Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi INSIDE 2 Inauguration of Academic Activities 2017 3 Graduation Ceremony 2017 4 Ramayanam Day Celebrations Teachers’ Day 5 Sanskrit Day and Onam Celebrations SPICMACAY - Lecture Demonstration 6 Keralapiravi 2017 Blood Donation Camp 7 Department of Computer Science and IT Hands on Workshop on Python 12 Department of Commerce and Management National Seminar on Scientific Research Writing 16 Department of Visual Media and Communication Journalism Seminar, Ramoji Rao Film City Visit 17 Chitrakala Kalari - Art Camp Nature Camp 18 ‘Karutha Juthan’ - Film Screening Advertising Workshop 19 R 4 Respect 21 Interpreting Resonance Workshop on Script Writing and Film Production 22 Clay Modelling Workshop Visit to Kerala Kalamandalam 23 Department of English and Languages Workshop on Research Methodology for Humanities 24 Two Day National Seminar “Singular Plural 150th Birth Anniversary of Sister Nivedita 27 Department of Mathematics National Workshop on Latex Report and Article writing 28 Corporate and Industry Relations (CIR) Placement Profile Inauguration of Academic Activities 2017 Inauguration of academic activities 2017, 15th Annual Kochi. The Guest of Honour Smt. P. Sindhu, Unit series of Vidyamritam Extramural lectures and Manager, Mathrubhumi offered felicitations. The Activities of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) chief guest launched the academic handbook. As was held on Wednesday, 26th July, 2017. The event part of the CSR activities of the campus, saplings commenced with the Ganapathy stuthi and an were distributed to the parents in association with astounding dance performance. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kollam City District from 07.06.2020To13.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kollam City district from 07.06.2020to13.06.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Police father of which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Accused Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr.1918/20, 188, 269, 270 IPC & 4(2)(a) USHA NAGAR, r/w 5 of Male, 1 SREE RAVI RAJAGOPALA MUSALIAR NAGAR - Chinnakkada 07-06-2020 Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail Age:40 N NAIR 25, KILIKOLLOOR Epidemic Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.1919/20, 188, 269, 270 IPC & 4(2)(a), PAYIPPADU 4(2)(h) r/w 5 Male, 2 BIJU BABU VEEDU, TALUK Thaluk 07-06-2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail Age:47 CUTCHERY, KOLLAM Epidemic Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.1920/20, 188, 269, 270 IPC & 4(2)(a), SAJEENA MANZIL, 4(2)(h) r/w 5 Male, PUTHUVAL 3 ASHOKAN KUTTAN Link Road 07-06-2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail Age:52 PURAYIDAM, Epidemic PULLIKKADA Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.1921/20, 188, 269, 270 SANTHOSH IPC & 4(2)(a), BHAVAN, 4(2)(h) r/w 5 Male, 4 SANTHOSH DESINGANADU Asramom 07-06-2020 of Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail SADANANDAN Age:58 NAGAR -145, Epidemic ASRAMAM Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.1922/20, 188, 269, 270 PUTHUVAL IPC & 4(2)(a) PURAYIDAM, r/w 5 of SAJAN Male, 5 VARGESE NETHAJI NAGAR - Asramom 07-06-2020 Kerala Kollam East SI of Police Station Bail VARGESE Age:28 20, MUNDAKKEL Epidemic WEST Disease Ordinance 2020 Cr.1923/20, 188, -

Social Spaces and the Public Sphere

Social Spaces and the Public Sphere: A spatial-history of modernity in Kerala, India Harikrishnan Sasikumar B.Sc., M.A A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law and Government, Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr Kenneth McDonagh January 2020 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work, that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: (Candidate) ID No.: 15212205 Date: Dedicated to my late grandmother P.V. Malathy who taught me so much about Kerala’s culture; late uncle Prof. T. P. Sreedharan who taught me about its politics; and late Dr Vineet Kohli who taught me the importance of questioning Your absence is forever felt. Acknowledgements When I decided to pursue my PhD in 2015, I was told to expect a tedious and lonely journey. But the fact that I feel like the last five years passed quickly is also testimony that the journey was anything but lonely; and for this, I have a number of people to thank. My utmost gratitude firstly to my supervisor Dr Kenneth McDonagh for his patient and continued guidance and support, and for reminding me to “come back” to my question every time I wandered too far. -

Kavya Bharati

KAVYA BHARATI THE STUDY CENTRE FOR INDIAN LITERATURE IN ENGLISH AND TRANSLATION AMERICAN COLLEGE MADURAI Number 11 1999 Kavya Bharati is a publication of the Study Centre for Indian Literature in English and Translation, American College, Madurai 625 002, Tamilnadu, India. Opinions expressed in Kavya Bharati are of individual contributors, and not necessarily of the Editor and Publisher. Kavya Bharati is sent to all subscribers in India by Registered Parcel Post. It is sent to all international subscribers by Air Mail. Annual subscription rates are as follows: India Rs. 100.00 U.S.A. $12.00 U.K. £ 8.00 Drafts, cheques and money orders must be drawn in favour of "Study Centre, Kavya Bharati". For domestic subscriptions, Rs.15.00 should be added to personal cheques to care for bank charges. All back issues of Kavya Bharati are available at the rates listed above. From Number 3 onward, back issues are available in original form. Numbers 1 and 2 are available in photocopy book form. All subscriptions, inquiries and orders for back issues should be sent to the following address: The Editor, Kavya Bharati SCILET, American College Post Box 63 Madurai 625 002 (India) Registered Post is advised wherever subscription is accompanied by draft or cheque. Editor: R.P. Nair FOREWORD A New Decade! No, this is not a reference to the calendar. It is Kavya Bharati's new decade which begins with this issue number eleven, and we are rather excited about it. What's new in this issue is primarily the many "new" poets who are publishing here for the first time. -

M.A Hindi Syllabus

KANNUR UNIVERSITY (Abstract) MA Hindi Programnre under Choice Based Credit Semester System in the Department- Revised Scheme, Syllabus & Model Question Papers Implemented rvith effect frorn 2015 admission- Orders issued. ACADEMIC 'C'SECTION U.O. No.Ac ad/C3 I 48441201 5 Civil Station P.O, Dated,0 4-11 -2015 Read : 1. U.ONo.Acad/C312049/2009 dated I 1.10.2010. 2. U.O No.Acadlc312049/2009 dated 05.04.201L 3. Meeting of the Syndicate Sub-Committee held on 16.01.2015. 4.Meeting of the Department Council held on 17.03.2015. 5. Meeting of the Curriculum Committee held on 10.04.2015. 6. U.O No.Acad/C411453612014 dated 29.05.2015. .' 7. Letter from the Course Director, Dept.of Hindi, Dr. P.K.Rajan Memorial Carrpus 8. Meeting of the Curriculum Committee held on 03.09.2015. ORDER l.The Regulations for Post Graduate Progmmmes under Choice Based Credit Semester System were implemented in the Schools/Departments of the University with effect from 2010 admission as per the paper read (1)aboveand certain modifications were effected to tlre same vide paper read(2). 2.The meeting of the Syndicate Sub-Commitlee reconrmended to revise the sclreme and Syllabus of all the Post Graduate Programmes in the University Schools/Departments under Choice Based Credit Semester System (CCSS) with effect from 2015 admission vide paper read (3)above. 3. The Depaftment Council vide paper read (4) above has approved the Scheme, Syllabus & Model Question Papers for MA Hindi Programme under Choice Based Credit Semester System(CCSS) for implementation with effect from 2015 admission. -

History of Modern Kerala

HISTORY OF MODERN KERALA QUESTION BANK HISTORY OF MODERN KERALA BA HISTORY – CORE COURSE VI Semester CUCBCSS 2017 Admission onwards SCHOOLOF DISTANCE EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Prepared by: Dr. Sreevidhya Vattarambath Assistant Professor Department of History K K T M Govt. College, Pullut. 1. Captain Keeling reached Calicut in the year a. 1615 b. 1614 c.1812 ed. 1712 2. The British attained a sandy plot of land at Attingal from a. Dutch b French c. Rani of Attingal d. Portuguese 3. The most serious and widest revolt against the British in South India was a. Attingal Outbreak b. Revolt of Padinjare Kovilakam Rajas c. Kurichia Revolt d. Pazhassi Revolt 4. The author of the novel Kerala Simham is a.K. M Panikkar b. P K K Menon c. T.P.Sankaran kutty Nair d.William Logan 5. The leader of Kurichia revolt was a. Thalakkal Chandu b. Kunnavath Sankaran Nambiar c.Raman Naby d.Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja 6. The year in which Veluthamby had done his famous Kundara Proclamation a. 1808 b. 1807 c. 1810 d.1809 7. The Dewan of Travacor e who made Pathiramanal of Vembanattukayal as suitable for human life. a. Col. Muroe b.Macaulay c. P Rajagopalachari d. Veluthamby Dalawa 8.The fundamental caused for the agrarian problems in the 19th century in Malabar was a. Economic reforms introduced by the British in Malabar b.Agrarian reforms of the British Government c. Exploitation of the Jenmies d. Religious fanaticism of the Mappilas 9.According to------------- the first revolt of the Mappilas of Malabar took place at Pantallur in 1836. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh a large number of languages in India, and we have lots BHASHA SAMMAN of literature in those languages. Akademi is taking April 25, 2017, Vijayawada more responsibility to publish valuable literature in all languages. After that he presented Bhasha Samman to Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao, Prof. T.R Damodaran and Smt. T.S Saroja Sundararajan. Later the Awardees responded. Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao expressed his gratitude towards the Akademi for the presentation of the Bhasha Samman. He said that among the old poets Mahakavai Tikkana is his favourite. In his writings one can see the panoramic picture of Telugu Language both in usage and expression. He expressed his thanks to Sivalenka Sambhu Prasad and Narla Venkateswararao for their encouragement. Prof. Damodaran briefed the gathering about the Sourashtra dialect, how it migrated from Gujarat to Tamil Nadu and how the Recipients of Bhasha Samman with the President and Secretary of Sahitya Akademi cultural of the dialect has survived thousands of years. He expressed his gratitude to Sahitya Akademi for Sahitya Akademi organised the presentation of Bhasha honouring his mother tongue, Sourashtra. He said Samman on April 25, 2017 at Siddhartha College of that the Ramayana, Jayadeva Ashtapathi, Bhagavath Arts and Science, Siddhartha Nagar, Vijayawada, Geetha and several books were translated into Andhra Pradesh. Sahitya Akademi felt that in a Sourashtra. Smt. T.S. Saroja Sundararajan expressed multilingual country like India, it was necessary to her happiness at being felicitated as Sourashtrian. She extend its activities beyond the recognized languages talked about the evaluation of Sourashtra language by promoting literary activities like creativity and and literature. -

Prog Schedule

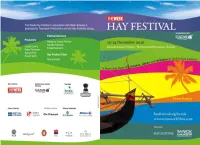

Teamwork Productions Teamwork is a highly versatile entertainment company, with roots in the performing arts, social action, and the corporate world. Our expertise lies in the area of Entertainment including Television, Filmdocumentary and feature, Event Management, Social Communication, Creation and Development of Contemporary Performing and Visual Arts Festivals across the world, and in nurturing new talent across arts forms. Teamwork currently produces performing and visual arts festivals across the world including in thors a n d S ep a k e rs Edinburgh, Hong Kong, London, Madrid, Melbourne, New York, Chicago, Vancouver,Perth, ating Au Singapore, Johannesburg, Durban, Cape Town and New Zealand. ticip Par Miguel Syjuco Teamwork produces the immensely popular Jaipur Literature Festival, an annual event where over Hannah Rothschild N S Madhavan Sebastian Faulks a hundred authors from across the world come together over a five day period. The annual week Adoor Gopalakrishnan Jaishree Misra Namita Gokhale Shashi Tharoor long Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META) in New Delhi is produced by teamwork for the Amrita Tripathi last five years. In 2009, Teamwork produced the Bonjour India: Festival of France, with more than Jisha Krishnan Nik Gowing Shobhaa De Anita Nair 200 events across 18 cities in India and featuring over 250 artists, designers, researchers & Jorge Volpi Nikita Doval Shoma Chaudhury Anita Sethi entrepreneurs. K. Satchidanandan Nilanjana S Roy Simon Schama Bama Faustina K.S. Sachidananda ONV Kurup Sister Jesme Basharat Peer The Hay Festival (UK) Murthy Paul Henry Sonia Faleiro N.Bhanutej Hay Festival has been running for 23 years. In that time the company has developed to become an Kishwar Desai Paul Zacharia Tarun Tejpal Bob Geldof international festival production team. -

MA-English-2019.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Curriculum and Syllabus for Postgraduate Programme in English Under Credit Semester System (with effect from 2019 admissions) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I place on record my heartfelt gratitude to the members of the Board of Studies, Department of English, for their cooperation and valuable suggestions. I acknowledge their sincere efforts to scrutinize the draft curriculum and make necessary corrections. Dr. Sabu Joseph Chairman Board of Studies BOARD OF STUDIES CHAIRMAN NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr Sabu Joseph Associate Professor Department of English St Berchmans College Changanacherry - 686101 SUBJECT EXPERTS NOMINATED BY THE COLLEGE ACADEMIC COUNCIL NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr Vinod V Balakrishnan Professor of English Department of Humanities and Social Sciences National Institute of Technology Tiruchirappalli- 620015 Dr Babu Rajan P P Assistant Professor Department of English Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit Kalady EXPERT NOMINATED BY THE VICE-CHANCELLOR NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr K M Krishnan Director, School of Letters M G University, Kottayam ALUMNI REPRESENTATIVE NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr. Rekha Mathews Associate Professor and Head B K College, Amalagiri MEDIA AND ALLIED AREAS NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr Paul Manalil Former Director Kerala State Institute of Children’s Literature and Former Assistant Editor, Malayala Manorama TEACHERS FROM THE DEPARTMENT NOMINATED BY THE PRINCIPAL TO THE BOARD OF STUDIES TEACHER’S NAME AREA OF SPECIALISATION Josy Joseph Shakespeare Studies, Literary Theory Dr Benny Mathew Indian Writing