CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE the Double Bass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bottesini Enjoyed a Globe-Trotting Career As “The Paganini of the Double Bass” but Was Also an Accomplished and Respected Conductor in Europe

NAXOS NAXOS Giovanni Bottesini enjoyed a globe-trotting career as “the Paganini of the double bass” but was also an accomplished and respected conductor in Europe. When conducting operas Bottesini would often perform fantasies on the evening’s entertainment during the intermission. Two such fantasies, ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’ and ‘Beatrice di Tenda’, are virtuosic tours de force in which the complex double bass figurations mimic the coloratura vocal writing of the day. In keeping with this vocal 8.570399 BOTTESINI: style, this recording also includes the song Une bouche aimée with double bass obbligato, most likely BOTTESINI: performed on one of Bottesini’s frequent concert tours with various leading sopranos of the day. DDD Giovanni Playing Time BOTTESINI 71:55 (1821-1889) Fantasia ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’ 1 Fantasia ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’ 10:52 Fantasia ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’ 2 Romanza drammatica 8:25 3 Introduzione e bolero 8:50 4 Romanza: Une bouche aimée * 5:12 5 Capriccio di bravura 9:14 6 Elégie in D 5:24 7 Fantasia ‘Beatrice di Tenda’ 11:47 8 Grande Allegro di Concerto 12:11 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English Kommentar auf Deutsch Naxos Rights International Ltd. ൿ 1992 & Thomas Martin, Double Bass Anthony Halstead, Piano Ꭿ Jacquelyn Fugelle, Soprano * 2008 Includes Free Downloadable Bonus Track available at www.classicsonline.com. Please see inside booklet for full details. The sung text and English translation included 8.570399 These can also be accessed at www.naxos.com/libretti/570399.htm 8.570399 Recorded at CTS Studios, Wembley, London, UK in November 1982 and February 1984 Producer: Chris Hazell Engineer: Dick Lewzey Previously released on ASV CD DCA 626 Booklet notes: Francesca Franchi Cover Picture: Double Bass by Carlo Antonio Testore (1693–1765), Milan 1716 . -

Gunther Schuller Memorial Concert SUNDAY NOVEMBER 22, 2015 3:00 Gunther Schuller Memorial Concert in COLLABORATION with the NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY

Gunther Schuller Memorial Concert SUNDAY NOVEMBER 22, 2015 3:00 Gunther Schuller Memorial Concert IN COLLABORATION WITH THE NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY SUNDAY NOVEMBER 22, 2015 3:00 JORDAN HALL AT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY GAMES (2013) JOURNEY INTO JAZZ (1962) Text by Nat Hentoff THE GUARDIAN Featuring the voice of Gunther Schuller Richard Kelley, trumpet Nicole Kämpgen, alto saxophone MURDO MACLEOD, MURDO MACLEOD, Don Braden, tenor saxophone Ed Schuller, bass George Schuller, drums GUNTHER SCHULLER INTERMISSION NOVEMBER 22, 1925 – JUNE 21, 2015 THE FISHERMAN AND HIS WIFE (1970) Libretto by John Updike, after the Brothers Grimm Sondra Kelly Ilsebill, the Wife Steven Goldstein the Fisherman David Kravitz the Magic Fish Katrina Galka the Cat Ethan DePuy the Gardener GIL ROSE, Conductor Penney Pinette, Costume Designer Special thanks to the Sarah Caldwell Collection, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University. Support for this memorial concert is provided in part by the Amphion Foundation, the Wise Family Charitable Foundation, and the Koussevitzky Music Foundation. THE FISHERMAN AND HIS WIFE Setting: A seaside, legendary times Scene i A humble hut, with net curtains and a plain stool; dawn Scene ii Seaside; water sparkling blue, sky dawn-pink yielding to fair blue Scene iii The hut; lunchtime Scene iv Seaside; sea green and yellow, light faintly ominous Scene v A cottage, with a pleasant garden and velvet chair Scene vi Seaside; water purple and murky blue, hint of a storm Scene vii A castle, with a great rural vista, tapestries, and an ivory canopied bed CLIVE GRAINGER CLIVE Scene viii Seaside; water dark gray, definite howling of sullen wind Scene ix Flourishes and fanfares of brass THIS AFTERNOON’S PERFORMERS Scene x Seaside; much wind, high sea and tossing, sky red along edges, red light suffuses FLUTE TRUMPET HARP Kay Rooney Matthews Sarah Brady Terry Everson Amanda Romano Edward Wu Scene xi OBOE TROMBONE ELECTRIC GUITAR Nicole Parks Jennifer Slowik Hans Bohn Jerome Mouffe VIOLA Scene xii Seaside; storm, lightning, sea quite black. -

Domenico Dragonetti: a Case Study of the 12 Unaccompanied Waltzes

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-19-2020 10:00 AM Domenico Dragonetti: A case study of the 12 unaccompanied waltzes Jury T. Kobayashi, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Dr. James Grier, The University of Western Ontario : Dr. Peter Franck, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Music © Jury T. Kobayashi 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Kobayashi, Jury T., "Domenico Dragonetti: A case study of the 12 unaccompanied waltzes" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7058. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7058 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis uses the 12 waltzes composed by the famous double bass virtuoso, Domenico Dragonetti, as a case study to examine certain key aspects of his playing style. More specifically, this thesis seeks to answer the question: what aspects of Dragonetti’s playing could be deemed virtuosic? I select a number of instances in the waltzes where the demands posed by various passages suggest a specific solution required to execute the passage. I suggest various solutions to these passages that reveal the types of solutions Dragonetti might have employed and help shed light on my initial question. The analysis reveals that Dragonetti might have been an athletic musician who was agile across the fingerboard, and whose bow technique afforded him a large palette of articulations that helped him achieve polyphonic textures on the instrument. -

The Double Bass Development in China

THE LITHUANIAN ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND THEATRE FACULTY OF MUSIC STRING DEPARTMENT SHAONAN LI THE DOUBLE BASS DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Study Program: Music Performance (Double Bass) Master’s Thesis Advisor: assoc. prof., dr. Audra Versekėnaitė (signature)... ...................................... Vilnius, 2020 LIETUVOS MUZIKOS IR TEATRO AKADEMIJA SĄŽININGUMO DEKLARACIJA DĖL TIRIAMOJO RAŠTO DARBO 2020 m. gegužės 21 d. Patvirtinu, kad mano tiriamasis rašto darbas „The double bass development in China“ yra parengtas savarankiškai. 1. Šiame darbe pateikta medžiaga nėra plagijuota, tyrimų duomenys yra autentiški ir nesuklastoti. 2. Tiesiogiai ar netiesiogiai panaudotos kitų šaltinių ir/ar autorių citatos ir/ar kita medžiaga pažymėta literatūros nuorodose arba įvardinta kitais būdais. 3. Su pasekmėmis, nustačius plagijavimo ar duomenų klastojimo atvejus, esu susipažinęs(- usi) ir jas suprantu. Shaonan Li (Parašas) (Vardas, pavardė) 1 Abstract Master thesis “The Double Bass development in China” presents the introduction and development of this musical instrument in China. In the first chapter, the double bass in China, I will describe the efforts of early Chinese double bassists such as Zheng Daren (b. 1927) and Shao Genbao (b. 1930) to help the advancement of the instrument in the country. I will also portray the background of musical education in China at that time (1949–1979), with a focus on Zhengkai Ye (no information available so far), who strove to improve Chinese double bass students’ performance skills. I will also introduce some traditional Chinese folk instruments with similar techniques of playing, such as the erhu, a very beautiful traditional string instrument. Both the double bass and the erhu need a wonderful vibrato and good control of the player’s right hand, and both can be used to play the same repertoire, such as 《二泉映月》 (Two Springs Reflect the Moon), composed by Yanjun Hua (1893–1950) in 1949, or 《梁祝》 (Butterfly Lovers), composed by Zhanhao He (b. -

Bottesini's Greatest Hits

Bottesini’s Greatest Hits Acknowledgments Many thanks to my wife and superb cellist, Wendy, and sons Peter and Andrew, for your patience with my many hours away from home. Thanks to Texas Tech University, for its financial support, and the TTU School of Music for the use of the amazing Hemmle Recital Hall, and one of its beautiful Steinway concert grands. Of course, a recording project such as this requires some wizardry from the recording engineer. Thank you, Will Strieder, Professor of Trumpet, and director of the TTU School of Music’s recording studio for your patience, attention to detail, and your own special brand of virtuosity. —Mark Morton Recorded, Mixed and Mastered by Will Strieder in Hemmle Recital Hall, School of Music, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas. The recording took place intermittently over a great deal of time. The piano parts were recorded first, then the bass. The first piano tracks were recorded January 5, 2009, and the last bass track was recorded October 21, 2011. Cover Photo by Heather Ann Design Liner notes by Nickolas Miller Piano Technicians: Kevin Fortenberry and Dan McSpadden This recording was made possible in part by the office of the Provost of Texas Tech University. All works edited and arranged by Mark Morton. www.albanyrecords.com TROY1411/12 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd tel: 01539 824008 © 2013 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. -

Casts for the Verdi Premieres in the US (1847-1976)

Verdi Forum Number 2 Article 5 12-1-1976 Casts for the Verdi Premieres in the U.S. (1847-1976) (Part 1) Martin Chusid New York University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/vf Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chusid, Martin (1976) "Casts for the Verdi Premieres in the U.S. (1847-1976)" (Part 1), AIVS Newsletter: No. 2, Article 5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Verdi Forum by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Casts for the Verdi Premieres in the U.S. (1847-1976) (Part 1) Keywords Giuseppe Verdi, opera, United States This article is available in Verdi Forum: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/vf/vol1/iss2/5 Casts for the Verdi Premieres in the U.S. (1847-1976), Part 1 by Martin Chusid 1. March 3, 1847, I lombardi alla prima tioni (London, 1862). See also U.S. pre croclata (Mi~, 1843). New York, Palmo's mieres of Due Foscari, Attila, Macbeth and Opera House fn. 6 6 Salvatore Patti2 (Arvino) conducted w.p. Aida (Cairo, 1871). See Giuseppe Federico de! Bosco Beneventano 3 also U.S. premieres in note S. Max Maret (Pagano) zek, Crochets and Quavers (l8SS), claims Boulard (Viclinda) that Arditi was Bottesini's assistant. Clotilda Barili (Giselda) The most popular of all Verdi's early operas A. Sanquirico3 (Pirro) in the U.S. (1847-1976) Benetti Riese (Prior) 3. -

Download Booklet

572284bk Bottesini:570034bk Hasse 4/3/10 11:03 AM Page 4 Thomas Martin Thomas Martin studied in America under Harold Roberts, Oscar Zimmerman, and Roger Scott, and has held leading positions with the Buffalo Philharmonic and Israel Philharmonic Orchestras and as a principal with l’Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, the English Chamber Orchestra, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and latterly, the London Symphony Orchestra. He has been Principal Double Bassist with the Oxford Philomusica since its first season. He now also pursues an interest in solo playing, appearing in recitals and concertos with orchestras around the globe. He is Professor of Double Bass at London’s Royal College of Music and was appointed International Fellow of Double Bass at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music in September 2007, gives master-classes internationally, and is responsible for many editions of music for double bass. He has BOTTESINI served on many International Competition juries, and is also well known as a luthier, having so far made over 140 basses. Fantasia on Timothy Cobb Outside of his duties as principal bass of the Met Orchestra and Double Bass Faculty Chair at the Juilliard School, double bassist Timothy Cobb maintains a busy schedule of chamber collaborations and solo appearances. He themes of Rossini collaborates with well known quartets and distinguished colleagues. His festival appearances include most of the major summer festivals in the United States, and he serves as solo bassist for the St Barth’s Music Festival in January each year. He is also on the faculty of the Sarasota Music Festival each June, coaching and performing chamber Passioni amorose music. -

February 22 & 23, 2020 Coriolan Overture, Op

Happy Birthday, Herr Beethoven – February 22 & 23, 2020 Coriolan Overture, Op. 62 Ludwig van Beethoven 1770-1827 Plutarch, the Ancient Greek historian and biographer, tells the story of the Roman general Coriolanus, who defeated the Volscians in central Italy, southeast of Rome, and captured their city of Corioli in 493 B.C. According to the story, Coriolanus returned victorious to Rome, but soon had to flee the city when charged with tyrannical conduct and opposition to the distribution of grain to the starving plebs. He raised an army of Volscians against his own people but turned back after entreaties of his mother and his wife. The Volscians, however, regarding him as a traitor because of his indecisiveness, put him to death. The inspiration for Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture came neither from Plutarch nor from Shakespeare, who made him the subject of his play Coriolanus, but from a play by Heinrich Joseph von Collin – poet, dramatist and functionary in the Austrian Finance Ministry (Austria’s way of supporting its artists). Von Collin’s play was a philosophical treatise on individual freedom and personal responsibility. It premiered in 1802 to great acclaim, using incidental music derived from Mozart’s opera Idomeneo. Beethoven took just three weeks to compose the Coriolan Overture in January 1807. It was meant to stand on its own as a composition inspired by the play. The Overture was premiered in March at an all-Beethoven concert held in the palace of one of Beethoven’s patrons, Prince Lobkowitz. Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61 Ludwig van Beethoven 1770-1827 Despite the customary long gestation of his music, when pressed, Beethoven could work fast. -

Bottesini US 1/15/08 12:03 PM Page 5

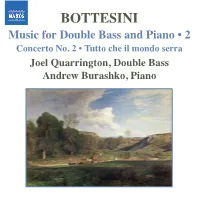

557042 bk Bottesini US 1/15/08 12:03 PM Page 5 Harold Hall Robinson 9 Une bouche aimée Beloved lips An internationally acclaimed artist, Harold Hall Robinson is currently the principal Une bouche aimée a dit à mon coeur: Beloved lips said to my heart: contrabassist with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Prior to this he spent ten seasons as principal “Viens, ô mon amour, ô toi, mon seul bonheur. “Come, O my love, O thou, my only joy. BOTTESINI bassist of the National Symphony Orchestra, eight seasons as associate principal of the Viens, ah! viens mon coeur, Come, ah, come, my heart, Houston Symphony Orchestra and three seasons as principal of the New Mexico Symphony ô toi, mon seul bonheur. O thou, my only joy. Orchestra. A prize-winner at the 1982 Isle of Man Solo competition, Harold Hall Robinson has Music for Double Bass and Piano • 2 performed concertos with the Philadelphia Orchestra, the National Symphony, Houston Adieu les tristes automnes. Farewell sad autumns, Symphony, New York Philharmonic, the Rhode Island Philharmonic, American Chamber Voici venir le printemps. Here comes the spring. Orchestra and the Greenville South Carolina Orchestra. In addition he is known for his La terre se couvre de fleurs, The earth is covered with flowers, Concerto No. 2 • Tutto che il mondo serra outstanding recitals and master classes throughout the United States. He is currently on the les rayons dorés ont tari ses pleurs. the golden rays have dried her tears. faculty of the Curtis Institute. Dans la feuille nouvelle In the new foliage Photo: Chris Lee chante la tourterelle. -

Giovanni Bottesini (1821-89) Double Bass Concerto No. 2 in B Minor (I) Allegro (Ii) Andante (Iii) Allegro

Giovanni Bottesini (1821-89) Double Bass Concerto no. 2 in B minor (i) Allegro (ii) Andante (iii) Allegro One of the most colourful – and mysterious – celebrities in nineteenth-century music is Giovanni Bottsini, the double bass virtuoso who also became a successful opera composer and conductor. Bottesini was to the double bass what Paganini was to the violin, or Liszt to the piano, a virtuoso supreme who astonished his audiences with effects previously unimaginable. At the age of fifteen he applied for a scholarship at the Milan Conservatory. On learning that there were only a few remaining places, including one reserved for double bass, he gave himself a crash course on the instrument, mastering enough technique to convince the selection panel he was worthy. He left the Conservatory four years later, taking with him a prize of 300 francs for solo playing. Soon he was touring the world as a principal bass and conductor for leading opera houses from Havana to London, delighting audiences during interval with his spectacular variations on arias from whatever opera was being presented. Bottesini must have been a splendid conductor. His friend, Giuseppe Verdi, entrusted him with the premier of Aïda in 1871. Bottesini also composed operas himself, at least ten, but none survives in the repertoire. His works for double bass, however, including two concertos, have become essential repertoire for bass players. But Bottesini was less than systematic in his paper work, and scholars are unable to date most of his works. Some, including his Second Concerto, survive only in piano reduction form, requiring others to create orchestral versions. -

559288 Bk Wuorinen US

559648 bk Serebrier US 25/5/10 16:00 Page 12 Also available: AMERICAN CLASSICS José SEREBRIER Symphony No. 1 Nueve: Double Bass Concerto Violin Concerto, ‘Winter’ Tango en Azul Casi un Tango They Rode Into The Sunset – 8.559183 Music for an Imaginary Film Simon Callow, Narrator Gary Karr, Double Bass Philippe Quint, Violin Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra and Chorus 8.559303 8.559648 12 José Serebrier 559648 bk Serebrier US 25/5/10 16:00 Page 2 José José Serebrier GRAMMY®-winning conductor and composer José Serebrier is one of most recorded classical artists today. He has SEREBRIER received 37 GRAMMY® nominations in recent years. When he was 21 years old, Leopold Stokowski hailed him as (b. 1938) “the greatest master of orchestral balance”. After five years as Stokowski’s Associate Conductor at New York’s Carnegie Hall, Serebrier accepted an invitation from George Szell to become Composer-in-Residence of the Cleveland Orchestra. Szell discovered Serebrier when he won the Ford Foundation American Conductors 1 Symphony No. 1 (1956) 19:24 Competition (together with James Levine). Serebrier was music director of America’s oldest music festival, in Worcester, Massachusetts, until he organized Festival Miami, and served as its artistic director for many years. In 2 Nueve: Double Bass Concerto (1971) 13:21 that capacity, he commissioned many composers, including Elliot Carter’s String Quartet No. 4, and conducted Simon Callow, Narrator many American and world premières. He has made international tours with the Juilliard Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Toulouse Gary Karr, Double bass Chamber Orchestra, National Youth Orchestra of Spain and many others. -

570397Bk Bottesini EU 20/2/08 16:28 Page 8

570397bk Bottesini EU 20/2/08 16:28 Page 8 Wieniawski et Papini. Un critique de l’époque écrivit: Gran Concerto en fa dièse mineur pour contrebasse “Il faut entendre Bottesini en personne pour découvrir et orchestre, probablement une oeuvre plus tardive, est les possibilités cachées dans le géant des instruments à la composition la plus accomplie de Bottesini pour la BOTTESINI cordes -, pour entendre ce qui peut se faire en matière de contrebasse. La première date que l’on connaisse pour sonorité, de ton, de légèreté d’expression et de grâce.” son exécution est mai 1878; une exécution à Londres eut Andante sostenuto pour cordes fut écrit en avril 1886. lieu en mars 1887, deux ans avant la mort de Bottesini. Gran Concerto in F sharp minor Bottesini avait joué régulièrement à Londres pendant les Dans son Gran Concerto, Bottesini ne se contente pas de quelques premiers mois de cette année-là, mais la composer une pièce remarquable. Tandis qu’il explore Gran Duo Concertante composition eut lieu à Naples, ceci suivant le schéma les ressources de l’instrument au maximum (un fait général de la vie de Bottesini à cette époque: il avait évident pour l’exécutant mais pas toujours pour tendance à partager son temps entre Londres, pour le l’auditeur), il adopte un style de composition plus Thomas Martin, Double Bass travail, et Naples, pour la détente. impliqué: il y a une introduction orchestrale longue, les Duetto pour clarinette et contrebasse fut joué à une modulations sont beaucoup plus audacieuses et José-Luis Garcia, Violin • Emma Johnson, Clarinet occasion notable au Royal Italian Opera House, Covent emmènent la contrebasse dans des tons qui ne sont pas Garden, en septembre, 1865, la partie de clarinette étant aussi précis que toniques et dominants.