An Annotated Bibliography for Double Bass Methods and Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

A Performer's Guide to Hertl's Concerto for Double Bass

A Performer's Guide To Frantisek Hertl's Concerto for Double Bass Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Roederer, Jason Kyle Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 15:16:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194487 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HERTL’S CONCERTO FOR DOUBLE BASS by Jason Kyle Roederer ________________________ Copyright © Jason Kyle Roederer 2009 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Jason Kyle Roederer entitled A Performer’s Guide to Hertl’s Concerto for Double Bass and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Patrick Neher _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Mark Rush _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Thomas Patterson Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Bassist Bryant Wilder's Fingerprints

NEWS MAGAZINE SHOP PLAYERS GEAR LEARN MEDIA WIN # ! + BASS CDS SUBSCRIBE NOW Bassist Bryant Wilder’s Get Cool Bass News! Fingerprints email address Subscribe By Bass Musician ! Published on August 18, 2020 ! Share " Tweet # Subscribe Bassist Robert Harper, Ride With Me Pluckwild Music Is thrilled to announce the release of the latest album from Bryant Wilder, Fingerprints, available everywhere on August 21, 2020. Fingerprints is an eclectic blend of incredible funk, salsa and gospel. # Interview with Bassist If you like Bruno Mars, you’ll love Fingerprints hit single, WtF ! Ricardo Martinez Trending (Where’s the Funk, featuring The Schtank Machine), an indisputable $ groove that will make you get to groovin’. BASS BOOKS ) The Beatles: Sgt Pepper’s Bass # 1 Bryant has held a bass since he was 14. Transcriptions ! The bassist, songwriter, arranger and producer has recorded and $ performed with artists such as Missy Elliot, The CD Hawkins Singers, BASS HISTORY ) Fretless Bass History New Kids On The Block and Shirley Caesar on many of the world # 2 greatest stages, including; Saturday Night Live, Radio City Music Hall, ! Interview with Bassist Carnegie Hall and Madison Square Garden (MSG). Fingerprints is his $ Mitch Friedman sophomore album, following The Right Track, which was released in BASS BOOKS ) 2004. Dream Theater Bass Transcriptions – Images # 3 And Words ! PluckWild Music is a production company devoted to making music $ that people want to hear. Productions blend live instrumentation and BASS BOOKS ) synthesizers that create intense low-end, head bobbing, feet tapping Tab Appendix – Grooving # songs that listeners hum for days. With Hybrid Techniques 4 ! Visit Bryant Wilder online at bryantwilder.com $ Interview with Bassist BASS GIVEAWAYS ) Teymur Phell The Summer Splash View More Music News Bass Musician Giveaway, 5 Sponsored by Elixir Strings ADVERTISEMENT You may also like.. -

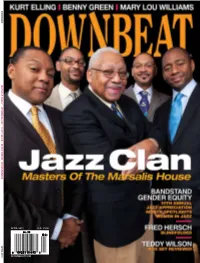

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

The String Family

The String Family When you look at a string instrument, the first thing you'll probably notice is that it's made of wood, so why is it called a string instrument? The bodies of the string instruments, which are hollow inside to allow sound to vibrate within them, are made of different kinds of wood, but the part of the instrument that makes the sound is the strings, which are made of nylon, steel or sometimes gut. The strings are played most often by drawing a bow across them. The handle of the bow is made of wood and the strings of the bow are actually horsehair from horses' tails! Sometimes the musicians will use their fingers to pluck the strings, and occasionally they will turn the bow upside down and play the strings with the wooden handle. The strings are the largest family of instruments in the orchestra and they come in four sizes: the violin, which is the smallest, viola, cello, and the biggest, the double bass, sometimes called the contrabass. (Bass is pronounced "base," as in "baseball.") The smaller instruments, the violin and viola, make higher-pitched sounds, while the larger cello and double bass produce low rich sounds. They are all similarly shaped, with curvy wooden bodies and wooden necks. The strings stretch over the body and neck and attach to small decorative heads, where they are tuned with small tuning pegs. The violin is the smallest instrument of the string family, and makes the highest sounds. There are more violins in the orchestra than any other instrument they are divided into two groups: first and second. -

20Questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker

20questions Interview by David Brent Johnson Photography by Steve Raymer for David Baker If Benny Goodman was the “King of Swing” periodically to continue his studies over the B-Town and Edward Kennedy Ellington was “the Duke,” next decade, leading a renowned IU-based then David Baker could be called “the Dean big band while expanding his artistic and Hero and Jazz of Jazz.” Distinguished Professor of Music at compositional horizons with musical scholars Indiana University and conductor of the Smithso- such as George Russell and Gunther Schuller. nian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, he is at home In 1966 he settled in the city for good and Legend performing in concert halls, traveling around the began what is now a world-renowned jazz world, or playing in late-night jazz bars. studies program at IU’s Jacobs School of Music. Born in Indianapolis in 1931, he grew up A pioneer of jazz education, a superlative in a thriving mid-20th-century local jazz scene trombonist forced in his early 30s to switch that begat greats such as J.J. Johnson and Wes to cello, a prolific composer, Pulitzer and Montgomery. Baker first came to Bloomington Grammy nominee and Emmy winner whose as a student in the fall of 1949, returning numerous other honors include the Kennedy 56 Bloom | August/September 2007 Toddler David in Indianapolis, circa 1933. Photo courtesy of the Baker family Center for the Performing Arts “Living Jazz Legend Award,” he performs periodically in Bloomington with his wife Lida and is unstintingly generous with the precious commodity of his time. -

Masked Marvels

THINKTANK RETAIL NICK GRAHAM SHOCKER ON WHY MEN MEN’S WEARHOUSE ARE THE NEW OUSTS GEORGE ZIMMER. WOMEN. PAGE MW2 WIND IN THEIR SAILS PAGE MW4 CREATURES OF THE WIND GETS NEW INVESTOR. PAGE 2 APPEAL EXPECTED Dolce and Gabbana Guilty in Tax Trial By LUISA ZARGANI SPRING 2014 MILAN — Guilty. That was the verdict handed down to Domenico MILAN Dolce and Stefano Gabbana, as well as four other MEN’S defendants, here Wednesday afternoon in the design- COLLECTION ers’ long-running tax evasion case. Judge Antonella THURSDAY, JUNE 20, 2013 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 PREVIEW Brambilla sentenced the designers and accountant Luciano Patelli to one year and eight months in jail, WWD plus legal expenses. Dolce’s brother Alfonso, gen- eral director Cristiana Ruella and fi nance director Giuseppe Minoni were sentenced to one year and four months in jail plus legal expenses. There is little chance the designers and the other defendants will serve any jail time because the sen- tences are below the two-year minimum generally re- quired in Italy to do so. The defendants were also charged with paying the Revenue Agency a provisional fi ne of 500,000 euros, or $668,650 at current exchange. The plaintiff solicitor Gabriella Valadia at the end of May asked for a provision- al fi ne of 10 million euros, or $13 million, citing damages to the image of the Revenue Service. Valadia at the time claimed that tax evasion “shows a system that is not cred- ible and effi cacious, it hurts the credibility of the Italian fi scal system, aggravated by the fact that the individuals at the center of the trial are so famous.” The court’s fi ne is separate from one imposed by the Revenue Agency of more than 400 million euros, or $535 million at current exchange, at the end of March. -

Acoustical Studies on the Flat-Backed and Round- Backed Double Bass

Acoustical Studies on the Flat-backed and Round- backed Double Bass Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorats der Philosophie eingereicht an der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien von Mag. Andrew William Brown Betreuer: O. Prof. Mag. Gregor Widholm emer. O. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Franz Födermayr Wien, April 2004 “Nearer confidences of the gods did Sisyphus covet; his work was his reward” i Table of Contents List of Figures iii List of Tables ix Forward x 1 The Back Plate of the Double Bass 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 The Form of the Double Bass 2 1.3 The Form of Other Bowed Instruments 4 2 Surveys and Literature on the Flat-backed and Round-backed Double Bass 12 2.1 Surveys of Instrument Makers 12 2.2 Surveys Among Musicians 20 2.3 Literature on the Acoustics of the Flat-backed Bass and 25 the Round-Backed Double Bass 3 Experimental Techniques in Bowed Instrument Research 31 3.1 Frequency Response Curves of Radiated Sound 32 3.2 Near-Field Acoustical Holography 33 3.3 Input Admittance 34 3.4 Modal Analysis 36 3.5 Finite Element Analysis 38 3.6 Laser Optical Methods 39 3.7 Combined Methods 41 3.8 Summary 42 ii 4 The Double Bass Under Acoustical Study 46 4.1 The Double Bass as a Static Structure 48 4.2 The Double Bass as a Sound Source 53 5 Experiments 56 5.1 Test Instruments 56 5.2 Setup of Frequency Response Measurements 58 5.3 Setup of Input Admittance Measurements 66 5.4 Setup of Laser Vibrometry Measurements 68 5.5 Setup of Listening Tests 69 6 Results 73 6.1 Results of Radiated Frequency Response Measurements 73 6.2 Results of Input Admittance Measurements 79 6.3 Results of Laser Vibrometry Measurements. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

Excellence in the Arts Since 1944

EXCELLENCE IN THE ARTS SINCE 1944 History The Lawson Academy of the Arts at Converse College has provided opportunities for arts education in the Spartanburg community for 72 years. Founded in 1944 by Alia Lawson as the Converse Pre-College, the program originally began as a “lab school” training college music students in the art of teaching music. While this original purpose is still a significant part of our program, we have expanded to include so much more. From the Director Our outstanding, dedicated faculty offer individual lessons in voice and nearly all instruments, as well as group classes in several areas. These opportunities cover every age range, from preschool to retired older adults and everyone in between. In the summer, Converse students staff our Fine Arts Day Camp, where children attend daily classes in visual arts, creative writing, music, dance, and theatre. The arts are so important in today’s society. Here at the Lawson Academy, we have something for everyone, whether it is taking private lessons, participating in a class or ensemble, or simply attending some delightful performances by our students and faculty. While our offerings may change throughout the year, the most up-to-date information will be available on our website listed below. Please join us and make the arts an integral part of your life! Contact Us Dr. Valerie MacPhail Janae O’Shields Director, Lawson Academy Assistant Director, Lawson Academy Director, Fine Arts Day Camp * Member of the National Guild for Office Hours: Community Arts Education since -

Domenico Dragonetti: a Case Study of the 12 Unaccompanied Waltzes

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-19-2020 10:00 AM Domenico Dragonetti: A case study of the 12 unaccompanied waltzes Jury T. Kobayashi, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Dr. James Grier, The University of Western Ontario : Dr. Peter Franck, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Music © Jury T. Kobayashi 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Kobayashi, Jury T., "Domenico Dragonetti: A case study of the 12 unaccompanied waltzes" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7058. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7058 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis uses the 12 waltzes composed by the famous double bass virtuoso, Domenico Dragonetti, as a case study to examine certain key aspects of his playing style. More specifically, this thesis seeks to answer the question: what aspects of Dragonetti’s playing could be deemed virtuosic? I select a number of instances in the waltzes where the demands posed by various passages suggest a specific solution required to execute the passage. I suggest various solutions to these passages that reveal the types of solutions Dragonetti might have employed and help shed light on my initial question. The analysis reveals that Dragonetti might have been an athletic musician who was agile across the fingerboard, and whose bow technique afforded him a large palette of articulations that helped him achieve polyphonic textures on the instrument.