Food Retail Sector in Mozambique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analisys of Incentives and Disincentives for Cotton In

ANALYSIS OF INCENTIVES AND DISINCENTIVES FOR COTTON IN MOZAMBIQUE OCTOBER 2012 This technical note is a product of the Monitoring African Food and Agricultural Policies project (MAFAP). It is a technical document intended primarily for internal use as background for the eventual MAFAP Country Report. This technical note may be updated as new data becomes available. MAFAP is implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in collaboration with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and national partners in participating countries. It is financially supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and FAO. The analysis presented in this document is the result of the partnerships established in the context of the MAFAP project with governments of participating countries and a variety of national institutions. For more information: www.fao.org/mafap Suggested citation: Dias P., 2012. Analysis of incentives and disincentives for cotton in Mozambique. Technical notes series, MAFAP, FAO, Rome. © FAO 2013 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 13 to 19

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 13 TO 19 MAY 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 654.1789 0.0015 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1305 0.2421 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 93.8650 0.0107 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 40.3500 0.0248 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.2830 0.7795 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 8.8351 0.1132 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8248 1.2125 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 58.5800 0.0171 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.0341 0.0713 BELGIUM EUR 0.8248 1.2125 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8248 1.2125 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 10.7009 0.0935 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.3838 0.7227 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.2227 0.1915 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 380.4786 0.0026 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7082 1.4121 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0322 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1967.5281 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.2889 0.1206 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2117 0.8253 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.4384 0.1553 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 152.0684 0.0066 CUBAN PESO CUP 24.1824 0.0414 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.7380 0.2675 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8248 1.2125 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8248 1.2125 CZECH KORUNA CZK 20.9986 0.0476 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.1333 0.1630 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 74.1987 0.0135 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.6800 0.0638 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 983.6942 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 42.6642 0.0234 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8248 1.2125 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3251 0.7547 FINLAND EUR 0.8248 1.2125 SPAIN EUR 0.8248 1.2125 FRANCE EUR 0.8248 1.2125 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.0341 0.0713 GERMANY -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

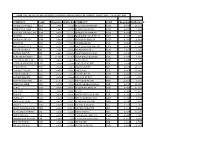

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

The Discovery of the Sea

The Discovery of the Sea "This On© YSYY-60U-YR3N The Discovery ofthe Sea J. H. PARRY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London Copyrighted material University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Copyright 1974, 1981 by J. H. Parry All rights reserved First California Edition 1981 Published by arrangement with The Dial Press ISBN 0-520-04236-0 cloth 0-520-04237-9 paper Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 81-51174 Printed in the United States of America 123456789 Copytightad material ^gSS3S38SSSSSSSSSS8SSgS8SSSSSS8SSSSSS©SSSSSSSSSSSSS8SSg CONTENTS PREFACE ix INTROn ilCTION : ONE S F A xi PART J: PRE PARATION I A RELIABLE SHIP 3 U FIND TNG THE WAY AT SEA 24 III THE OCEANS OF THE WORI.n TN ROOKS 42 ]Jl THE TIES OF TRADE 63 V THE STREET CORNER OF EUROPE 80 VI WEST AFRICA AND THE ISI ANDS 95 VII THE WAY TO INDIA 1 17 PART JJ: ACHJF.VKMKNT VIII TECHNICAL PROBL EMS AND SOMITTONS 1 39 IX THE INDIAN OCEAN C R O S S T N C. 164 X THE ATLANTIC C R O S S T N C 1 84 XJ A NEW WORT D? 20C) XII THE PACIFIC CROSSING AND THE WORI.n ENCOMPASSED 234 EPILOC.IJE 261 BIBLIOGRAPHIC AI. NOTE 26.^ INDEX 269 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1 An Arab bagMa from Oman, from a model in the Science Museum. 9 s World map, engraved, from Ptolemy, Geographic, Rome, 1478. 61 3 World map, woodcut, by Henricus Martellus, c. 1490, from Imularium^ in the British Museum. -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities September 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

ZIMRA Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for Period 24 Dec 2020 To

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 24 DEC 2020 - 13 JAN 2021 ZWL CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATECURRENCY CODE CROSS RATEZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 7.9981 0.1250 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 0.0497 20.1410 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 1.0092 0.9909 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 0.4819 2.0753 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 0.0162 61.7367 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 0.8994 1.1119 AUSTRIA EUR 0.0100 99.6612 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 0.9115 1.0972 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.0046 217.5176 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 0.1792 5.5819 BELGIUM EUR 0.0100 99.6612 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.0100 99.6612 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 0.1322 7.5356 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 0.0173 57.6680 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 0.0631 15.8604 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 4.7885 0.2088 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.0091 109.5983 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 11.0048 0.0909 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 23.8027 0.0420 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 0.1068 9.3633 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 0.0158 63.4921 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.0047 212.7090 CHINESE RENMINBI YUANCNY 0.0800 12.5000 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 1.9648 0.5090 CUBAN PESO CUP 0.3240 3.0863 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 0.0452 22.1111 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 PORTUGAL EUR 0.0100 99.6612 CZECH KORUNA CZK 0.2641 3.7860 QATARI RIYAL QAR 0.0445 22.4688 DANISH KRONER DKK 0.0746 13.4048 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 0.9287 1.0768 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 0.1916 5.2192 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 12.0004 0.0833 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 0.4792 2.0868 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 0.0459 21.8098 EURO EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 0.0163 61.2728 FINLAND EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SPAIN EUR 0.0100 99.6612 FRANCE EUR 0.0100 99.6612 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 0.1792 5.5819 GERMANY EUR 0.0100 99.6612 -

On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation

18485_CATO-R2(pps.):Layout 1 8/7/09 3:55 PM Page 353 On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok Zimbabwe experienced the first hyperinflation of the 21st centu - ry. 1 The government terminated the reporting of official inflation sta - tistics, however, prior to the final explosive months of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation. We demonstrate that standard economic theory can be applied to overcome this apparent insurmountable data problem. In consequence, we are able to produce the only reliable record of the second highest inflation in world history. The Rogues’ Gallery Hyperinflations have never occurred when a commodity served as money or when paper money was convertible into a commodity. The curse of hyperinflation has only reared its ugly head when the supply of money had no natural constraints and was governed by a discre - tionary paper money standard. The first hyperinflation was recorded during the French Revolution, when the monthly inflation rate peaked at 143 percent in December 1795 (Bernholz 2003: 67). More than a century elapsed before another hyperinflation occurred. Not coincidentally, the inter- Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. Alex K. F. Kwok is a Research Associate at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University. 1In this article, we adopt Phillip Cagan’s (1956) definition of hyperinflation: a price level increase of at least 50 percent per month. -

Searching for the Ancient Harbours of the Erythraean Sea Wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui an Analytical Investigation

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasd fghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq Searching for the Ancient Harbours of the Erythraean Sea wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui An Analytical Investigation 30/9/2010 opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg Carmen Tânia Macleroy Obied hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................................................................... 11 ͞,ĂƌďŽƵƌƐĂŶĚ/ŶĚŽ-ZŽŵĂŶdƌĂĚĞ͟ 1.1. Aims and Research Questions......................................................................................................................................... 11 1.1.1. PROPOSED RESEARCH ................................................................................................................................................. 11 1.1.2. AIMS ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Archaeological Reconnaissance in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique

Northwards from Sofala: Archaeological Reconnaissance in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique Nathan Anderson 1 1 Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter, Exeter United Kingdom. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Abstract: Visits made to archaeological sites in Cabo Delgado province, Mozambique, in early 2018 revealed a landscape rich in relatively under-researched cultural heritage, some of which is threatened by growing Islamic insurgency. Archaeological reconnaissance was conducted by the author to determine which sites were best suited to serve as case studies for his PhD research into the Islamisation of northern Mozambique. This pre-survey prioritized previously recorded Swahili sites in the southern Quirimbas Archipelago, namely on the islands of Ibo, Matemo, and Quirimba, as well as a cluster of sites on Cape Delgado, M’buizi and Tungi. However, possible new sites were documented during the visits to Cape Delgado and are detailed below. All locales visited contained artefacts dating primarily to the mid-second millennium AD, but absolute chronologies have not been determined as most of the sites visited have not been adequately examined. A dearth of cultural heritage protection schemes in the far northern region of Mozambique leaves conspicuous archaeological remains vulnerable to opportunistic looting and intentional damaging. Instances of both types of destruction were observed by the author in 2018. KEYWORDS: Archaeology, East Africa, Islam, Mozambique, Swahili HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Anderson, N. 2020. Northwards from Sofala: Archaeological Reconnaissance in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique. Journal of African Cultural Heritage Studies, 2 (1), pp.53-79. DOI: http://doi.org/10.22599/jachs.41 Journal of African Cultural Heritage Studies Anderson Vol 2(Issue 1) Introduction The following is a summary of observations made by the author while touring archaeological sites in northern Mozambique, mid-March through late April 2018. -

Zanzibar: Its History and Its People

Zanzibar: its history and its people http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.PUHC025 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Zanzibar: its history and its people Author/Creator Ingrams, W.H. Publisher Frank Cass & Co., Ltd. Date 1967 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast, Tanzania, United Republic of, Zanzibar Stone Town, Tanzania Source Princeton University Library 1855.991.49 Rights By kind permission of Leila Ingrams. Description Contents: Preface; Introductory; Zanzibar; The People; Historical; Early History and External Influences; Visitors from the Far East; The Rise and Fall of the Portuguese; Later History of the Native Tribes; History of Modern Zanzibar.