Professor Diane Losche the Shadow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis: Most Credible Theory of Human Evolution Free Download

THE AQUATIC APE HYPOTHESIS: MOST CREDIBLE THEORY OF HUMAN EVOLUTION FREE DOWNLOAD Elaine Morgan | 208 pages | 01 Oct 2009 | Souvenir Press Ltd | 9780285635180 | English | London, United Kingdom Aquatic ape hypothesis In addition, the evidence cited by AAH The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis: Most Credible Theory of Human Evolution mostly concerned developments in soft tissue anatomy and physiology, whilst paleoanthropologists rarely speculated on evolutionary development of anatomy beyond the musculoskeletal system and brain size as revealed in fossils. His summary at the end was:. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Thanks for your comment! List of individual apes non-human Apes in space non-human Almas Bigfoot Bushmeat Chimpanzee—human last common ancestor Gorilla—human last common ancestor Orangutan—human last common ancestor Gibbon —human last common ancestor List of fictional primates non-human Great apes Human evolution Monkey Day Mythic humanoids Sasquatch Yeren Yeti Yowie. Thomas Brenna, PhD". I think that we need to formulate a new overall-theory, a new anthropological paradigm, about the origin of man. This idea has been flourishing since Charles Darwin and I think that many scientists and laymen will have difficulties in accepting the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis — as they believe in our brain rather than in our physical characteristics. Last common ancestors Chimpanzee—human Gorilla—human Orangutan—human Gibbon—human. I can see two possible future scenarios for the Aquatic Ape Theory. University The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis: Most Credible Theory of Human Evolution Chicago Press. Human Origins Retrieved 16 January The AAH is generally ignored by anthropologists, although it has a following outside academia and has received celebrity endorsement, for example from David Attenborough. -

Looking for Bigfoot LEVELED BOOK • O a Reading A–Z Level O Leveled Book Word Count: 714 Looking for Bigfoot

Looking for Bigfoot LEVELED BOOK • O A Reading A–Z Level O Leveled Book Word Count: 714 Looking for Bigfoot Written by Torran Anderson Illustrated by Norm Grock Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. Photo Credits: Page 2: © iStockphoto.com/JLF Capture; page 6: © Design Pics Inc./Alamy; page 8: © REUTERS; page 10: © Jesse Harlan Alderman/AP Images; page 11: © Anthony Robert La Penna/Bangor Daily News/The Image Works; page 12: Looking for © Topham/Fortean/The Image Works Bigfoot Looking for Bigfoot Written by Torran Anderson Level O Leveled Book © Learning A–Z Correlation Illustrated by Norm Grock Written by Torran Anderson LEVEL O Illustrated by Norm Grock Fountas & Pinnell M All rights reserved. Reading Recovery 20 DRA 28 www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com Bigfoot Around the World I Set a Trap! Bigfoot or Sasquatch Almas in the Yeti or Migoi in Hibagon in the United States Caucasus Mountains the Himalayas in Japan No one has ever caught Bigfoot before. and Canada Some people think the giant hairy creatures don’t even exist, but I think that Bigfoot is real. To prove it, I’m going to catch one tonight! Then I’m going to take it to school as my science fair project. I can’t wait to see the look on the other kids’ faces when I come to class with Bigfoot. I’m guaranteed to get first place in the science fair. Mapinguari Kikomba Orang Pendek Yowie in Brazil in Africa in Sumatra in Australia Table of Contents I Set a Trap! ............................................... -

TITLE Abstractu, the System Include a Description,Of. The

DOCUMENT RESUME Parmenter, Trevor R. TITLE Developing Independence TfiroUgh Work Prep ration_ Minerma Street Special_ School Augmanted Evaluation of Innovations Program Project `(76/644©) SPONS AGENCY Australian..SchoolsCommission, canberra. PUB DATE 78 NOTE 342p.; The preparation of thiS report wa supparte by the New South Wales State/ Evaluation;Sub- committe of the Australian-Schools ComMission- 'FDPS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS_ Conceptual Schemes; *Educabrs Men_ lly-Handiiappe Evaluation Methods; Foreign Countrie_s;Men4:atly. Handicapped-; Models; *Systems Approach; *Work Experience Programs -IDENTIFIERS- *Australia ABSTRACTu, 'Using a systems model ,with its componerits,of inputs -process, atel,witputs; the report evaluates a work eitperiencpprogram formildlyretaded.students at an-Australian special school, Data;,,, -colleted at each Stage of the 'evaluation is presented. Inputs into the system include a_description,of. the population and:itsteeds,, Along with the situational variables that impinge. upon jt...These include the characteristics and value systems of the S-chool -and -i community- and the current economic climate. The aims. and objectives of the-'program-Hare .outlined4 together .with the special programO, techniques, and resources which. were applied. These cover such areas-. as reading, mathematics, Occupationaltherapy,,indastrial arts,- social development, science, and language development-. The dynamics of the organization cif-the proCeSs -variables' are described. -Objecttve assesSment,both criterion-referenced and normative, of the.prograti outcomes are made in each of thecomponentareas. Ratings of the effectiveness of the program -by teachers, parents, students, and. employers are analyzed, along with the predictive value of vocational guidance-tests administered -to each student prior to -the Commencement of the program. (DDS) 4****** Reproductionssupplied by FDRS are the best that can be.made *- * from the' original document.' *** *** ******************************** ** * **** ** VI IV DEPARTNiA T,OFHEALT14. -

With Rex Gilroy

with REX GILROY N.Z Paranormalist, Mark Wallbank chats to the Grandfather of Yowie research in Australia The fossilised Tyrannosaurid footprint discovered by Rex Gilroy with casts of some of the many Yowie Rex Gilroy, Director of the Australian Yowie Research Rex Gilroy in Sydney’s Kuringai National Park on footprints from his collection, together with others from Centre, Katoomba, NSW studying the Wadbilliga Rex Gilroy, Director of the Australian Yowie Research you remember the moment when all the great discoveries I have made in Wednesday 5th May, 2010. When it was first discovered South-east Asia, China, Russia and North America. Dryopithecine fossil footprint. It is yet one more piece of Centre, Katoomba, NSW studying the Wadbilliga the yowie spark ignited and your a lifetime’s research. I have gathered the filled with leaf litter. Photo copyright © Rex Gilroy 2011 Photo copyright © Rex Gilroy 2013. evidence of an Australian primate presence in Pleistocene Dryopithecine fossil footprint. It is yet one more piece of obsession started? largest privately owned natural science times and earlier. Photo copyright © Rex Gilroy 2013. evidence of an Australian primate presence in Pleistocene I grew up on a farm on the Georges River collection in Australia, in the course times and earlier. Photo copyright © Rex Gilroy 2013. of the marsupial hide garments they wore/ fraternity. No-one can say that I have not Moa, three UFO books among others to at Lansvale, outside Cabramatta [born of which I have made many important wear. Being Homo erectus they also know carried out my research and gathered be put on disc and off to the printers in first heard about Rex Gilroy as Nov 8th 1943]. -

Australian Aboriginal Verse 179 Viii Black Words White Page

Australia’s Fourth World Literature i BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Australia’s Fourth World Literature iii BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Adam Shoemaker THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS iv Black Words White Page E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Black Words White Page Shoemaker, Adam, 1957- . Black words white page: Aboriginal literature 1929–1988. New ed. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 0 9751229 5 9 ISBN 0 9751229 6 7 (Online) 1. Australian literature – Aboriginal authors – History and criticism. 2. Australian literature – 20th century – History and criticism. I. Title. A820.989915 All rights reserved. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organization. All electronic versions prepared by UIN, Melbourne Cover design by Brendon McKinley with an illustration by William Sandy, Emu Dreaming at Kanpi, 1989, acrylic on canvas, 122 x 117 cm. The Australian National University Art Collection First edition © 1989 Adam Shoemaker Second edition © 1992 Adam Shoemaker This edition © 2004 Adam Shoemaker Australia’s Fourth World Literature v To Johanna Dykgraaf, for her time and care -

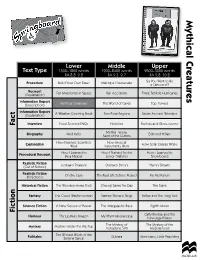

Mythical Creatures

Mythical Creatures Lower Middle Upper Text Type 1500–1800 words 1900–2400 words 2500–3000 words RA 8.8–9.2 RA 9.3–9.7 RA 9.8–10.2 So You Want to Be Procedure Build Your Own Easel Making a Cheesecake a Cartoonist? Recount (Explanation) Ten Milestones in Space Rail Accidents Three Terrible Hurricanes Information Report (Description) Mythical Creatures The World of Caves Top Towers Information Report (Explanation) A Weather Counting Book Two Polar Regions Seven Ancient Wonders Fact Interview Food Science FAQs Hobbies Fireflies and Glow-worms Mother Teresa: Biography Ned Kelly Saint of the Gutters Edmund Hillary How Forensic Scientists How Musical Explanation Work Instruments Work How Solar Energy Works How I Learned to How I Trained for the How I Learned to Procedural Recount Be a Nipper Junior Triathlon Snowboard Realistic Fiction (Out of School) Junkyard Treasure Outback Betty’s Harry’s Dream Realistic Fiction (In School) On the Case The Real-Life School Project Ms McMahon Historical Fiction The Wooden Horse Trick Cheung Saves the Day The Slave Fantasy The Cloud Washerwoman Sammy Stevens Sings Finbar and the Long Trek Science Fiction A New Source of Power The Intergalactic Race Eighth Moon Fiction Catty Bimbar and the Humour The Upstairs Dragon My Rhyming Grandpa New-Age Pirates The Mystery of The Mystery of the Mystery Mystery Under the Big Top Autoplane 500 Missing Food The Wicked Witch of the Folktales Singing Sands Gulnara Momotaro, Little Peachling We have designed these lesson plans so that you can have the plan in front of you as you teach, along with a copy of the book. -

Collectible Rarity Chart

Collectible Rarity Chart Mythic Epic Rare Popular Common Colors of the Animal Chances of finding Kingdom (Australia & U.S.) this Collectible Glitter Molded Rumble Popular Glitter Molded Squish Popular Andean Mountain Cat Epic Atlantic Puffin Rare Blue Damselfish Rare Calugo Common Eastern Spotted Newt Popular Golden Ghost Crab Common Golden Mantel Tree Kangaroo Mythic Green Vile Snake Common Hawaiian Honeycreeper Epic Honey Badger Common Kagu Rare Lear's Macaw Rare Livingston's Flying Fox Common Northern Glider Epic Red Fox Popular Red Mattella Frog Epic Sloth Common Yellow Tang Rare Wild Water Series Chances of finding (Australia & U.S.) this Collectible Rumble Mythic Crag Mythic Boof Mythic Ditty Mythic Squish Mythic Nap Mythic Atlantic Wolf Fish Popular Axolotl Popular Beluga Sturgeon Rare Bigeye Tuna Rare Cape Seahorse Common Giant Australian Cuttlefish Popular Giant River Otter Popular Golden Coin Turtle Rare Golden Sandfish Common Great Hammerhead Shark Popular Ocean Sunfish Epic Saimaa Ringed Seal Popular Short Nosed Sea Snake Epic Spotted Handfish Epic Tasmanian Giant Freshwater Crayfish Popular Trout Cod Epic Yellow Eyed Penguin Epic Zebra Shark Popular Super Series Chances of finding (Australia) this Collectible Rumble Mythic Squish Mythic Ditty Mythic Boof Mythic Crag Mythic Nap Mythic Gnash Epic Crusha Epic Super Series ctd. Chances of finding (Australia) this Collectible Ooze Popular Spark Epic Sludge Epic Crudd Epic Yog Epic Yopter Epic Yurt Popular African Bush Elephant Common Andean Bear Rare Bactrian Camel Popular Black -

Colin Groves 7:6-11

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 7:6-11 (2018) News IN MEMORIAM: COLIN GROVES Emeritus Professor Colin Groves passed away on 30 November 2017. He was 75. An eminent academic, Colin was an editorial board member of the Relict Hominoid Inquiry. A world-renowned taxonomist, mammologist, primatologist, paleoanthropologist, and biological anthropologist, he was also interested in cryptozoology— particularly in the possible existence of relict hominoids. To this subject he brought an open mind that expected a rigorous scientific approach from researchers. His clear and objective thinking, deep knowledge of mammals and hominins, articulate communication, and his generosity with his time were valuable assets to the editorial board of RHI and researchers. He was a member of the International Society of Cryptozoology, and I recall that he lamented the demise of the journal Cryptozoology, and much appreciated its re-emergence. Colin was awarded a BSc in Anthropology in 1963 (London), and in 1966, was awarded his PhD (London). He was invited to apply for a lectureship at the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University, arriving in Australia in 1974. In 1980, he was appointed Senior Lecturer; in 1988, Reader; in 2000, he was awarded a Professorship and upon his retirement in 2015, he was bestowed an emeritus position. During his career, he identified more than 50 species of animals. As late as November 2017, he was involved in the publication of research that identified a new species of orangutan in Sumatra, although, in his typical fashion, he downplayed his role in this research. He was researching and producing publications until just a week before he passed away. -

Yowie Script

THE YOWIE Written by Michael Brown [email protected] Registered WGAw Copyright (c) 2014 This screenplay may not be used or reproduced without the express written permission of the author FADE IN: EXT. BUSH - ABORIGINAL CAMP - NIGHT SUPERIMPOSE: Northern Territory, Australia A large campfire burns, spits, crackles under a perfect night sky. The nocturnal wildlife is vibrant and alive. Dust fills the air as a group of INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS painted in white symbols, holding spears begin their dance. Slow foot stomps are accompanied by boomerang clapsticks and a softly played didgeridoo - Their hunt begins. EXT. BUSH - SMALL CLEARING - CONTINUOUS The sound echoes through the bush and grabs the attention of two twenty something British campers. PHIL, ponytail, snob, and ZOE, his female equivalent jump out, excited, half naked from their tiny two man tent. PHIL You see, I told you we didn’t need to join that overpriced tour party. They rush around the tiny camp getting dressed. Zoe rummages through her bag. ZOE Yep, good call. (beat) Where’s the camera? The noise grows louder. Phil’s interest peaks, he ignores Zoe. PHIL Hurry up would ya! Getting a video of the Natives doing some sort of Tribal thing would be great for my travel story. Flustered, Zoe throws her bag to the floor and looks at Phil’s - A big bulge sticks out the side. She rummages through it, pulls out a video camera. PHIL (CONT’D) Oh good, you found it, let’s go. Phil hurries off - Leaves Zoe slightly annoyed. 2. PHIL (CONT’D) I think it’s coming from this direction. -

Yetis, Yowies and Dinosaur Trees: Amazing Finds in the Hunt for Living Legends

Yetis, Yowies and dinosaur trees: amazing finds in the hunt for living legends https://theconversation.com/yetis-yowies-and-dinosaur-trees-amazing-fin... 21 October 2013, 2.36pm AEST Bill Laurance Distinguished Research Professor and Australian Laureate at James Cook University You might think the idea of a Yeti is far-fetched, but don’t tell that to Oxford University Professor Bryan Sykes - or to the locals in Australian towns like Kilcoy and Woodenbong. Sykes created a global frenzy when he recently announced that the Yeti might well exist. His analyses were based on two hair samples collected 800 miles apart in the Woodenbong at sunrise: could a Yowie really be lurking in the Himalayas. surrounding woods? Flickr/gaw101 (Greg Wilson) When he analysed the DNA in those hairs, he found they perfectly matched the DNA of an ancient polar bear. According to Sykes, this could mean the polar bear is alive and kicking in the high Himalayas today. Those who claim to have seen the Yeti describe it as shaggy, bipedal and very shy, and Sykes reckons his ancient bear fits the ticket. People who study legendary creatures such as the Yeti or its Australian equivalent, the Yowie, are called cryptobiologists. They run the gamut from mainstream scientists to fringe types claiming to have been attacked by giant man-eating plants or kidnapped by aliens. But while the creatures they’re searching for can seem far-fetched, we shouldn’t dismiss cryptobiologists as cranks - because in their search for living legends, they have uncovered some amazing lost creatures. Yowie spotting in Australia Accounts of Yowies by Europeans hark back to 1876, when a report of an “indigenous ape” appeared in the Australian Town and Country Journal. -

Gun Violence | Climate Conversation | Missiles and Saucers | Searching for Yowie

Gun Violence | Climate Conversation | Missiles and Saucers | Searching for Yowie the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 40 No. 2 | March/April 2016 Published by the Center for Inquiry in association with the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry Ronald A. Lindsay, President Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org Fellows James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Barbara Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief of breast surgery Observatory, Williams College New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine section, Wayne State University School of Medicine. John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; Newton, MA Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, The Skeptic magazine (UK) Clifford A. Pickover, scientist, au thor, editor, IBM T.J. Watson Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er ad vo cate, Re search Center. Al len town, PA Sus an Haack, Coop er Sen ior Schol ar in Arts and Massimo Pigliucci, professor of philosophy, Willem Betz, MD, professor of medicine, Univ. of Brussels Sci en ces, professor of phi los o phy and professor of Law, Univ. of Mi ami City Univ. of New York–Lehman College Ir ving Bie der man, psy chol o gist, Univ. -

Grade 8 ELA Annotated 2014 State Test Questions

DRAFT New York State Testing Program Grade 8 Common Core English Language Arts Test Released Questions with Annotations August 2014 Copyright Information “Cowgirl Morning”: Reprinted by permission of CRICKET magazine, October 2010, Vol. 38, No. 2, text copyright © 2010 by Bryn Fleming, and illustrations copyright © 2010 by Ned Gannon. “A Bigfoot by Any Other Name” from TALES OF THE CRYPTIDES by Kelly Milner Halls, Rick Spears, and Roxyanne Young. Text copyright © 2006 by Kelly Milner Halls, Rick Spears, and Roxyanne Young. Reprinted with the permission of Darby Creek, a division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this text excerpt may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. “Cleaning Up”: Reprinted by permission of Cricket Magazine Group, Carus Publishing Company, from CICADA magazine March/April 2011, Vol. 13, No. 4, text © 2011 by Carus Publishing Company. “Summer of 2012—Too Hot to Handle?”—Science@NASA “The Inheritance of Tools” by Scott Russell Sanders, from THE NORTH AMERICAN REVIEW, March 1986, Vol. 271, No. 1, copyright © 1986 by North American Review. Used by permission of North American Review. All rights reserved. “Margaret’s Story”: Reprinted with the permission of Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. from THE THIRTEENTH TALE: A Novel by Diane Setterfield. Copyright © 2006 Diane Setterfield. Developed and published under contract with the New York State Education Department by NCS Pearson, Inc., 5601 Green Valley Drive, Bloomington, Minnesota 55437. Copyright © 2014 by the New York State Education Department. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced or transmitted for the purpose of scoring activities authorized by the New York State Education Department.