Vulnerability Brown Capability Brown Landscapes at Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Berkshire. [Kelly's

148 SA~DHl"RST. BERKSHIRE. [KELLY'S Browning Rev. George Albert [curate], Ballard John, White Swan P.R Norris Matthew, Wellington Arms P.H Devonshire cottage Barefoot George, Rose & Crown P.R Paice Waiter, farmer I"arrer William James, Sandhurst lodge Bennett Edward D. Bird-in-Hand P.R Parsons Charles, farmer, College farm Gascoigne Lieut.Col. W. J. }'orest end Blake Henry Robert, builder Priucess Charlotte of Wales's (Royal Harrison Rev. Charles [Wesleyan], Bhssett Edward, Railway tavern Berkshire Regiment), 1St Volunteer Cowper lodge llown Albert Orton, Jolly Farmers P.R Battalion (H. Co.) (Capt. Horace Harvey Lieut.-Col. George Sheppard Chambers James, grocer & baker Manders) R.A., J.P. Ambarrow Cooper Robf>rt, grocer Pearson Francis, shopkeeper Hawkins Mrs. Gothic villa Cox Josiah, farmer Pigg William Beechey, baker & grocer Majendie Miss, The Warren Crouch Frances (Miss), farmer Reynolds Elijah, Fox & Hounds P.R Malam Rev. Arthur Noel lILA. Eagle Delaney Patrick, dairyman Reynolds John 'rhos. drape!' & clothier' House school Dill Marcus Gordon Colquhoun,solicitor Rogers Edward, Prince of 'Vales P.H Orsborn Mrs. Sunny rest Earley Henry, beer retailer & grocer Russell James M.D. surgeon & medical Over Thomas Elmer George, grocer, White house officer & public vaccinator, Sandhurst Parsons Rev. the Hon. RandallILA.[rec- ' Evans George, saddler district, Easthampstead union tor], Rectory Giblett Robert, farmer Smith George, farmer, Breach farm Raleigh Edward WaIter Gillett Thomas, farmer, Snaprails farm Smith George, farmer Rose Rev. James [Baptist] GoddardSarahR.(Mrs.),Duke'sHeadp.R Taylor William, coal dlr. & shopkeeper Russell James M.D Groves Jas. Geo. farmer, Ambarrow hi Tice Charles, boot & shoe maker Sams Samuel Hills Thomas Chaplen, butcher Watts Herbert, poor rate & tax collector Thompson Capt. -

ARCHAEOLOGY the Newsletter of the Berkshire Archaeological Society

ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Berkshire Archaeological Society Autumn 2015 Vol.17, No.3 Dates for your diary Wednesday 2nd September 2015: Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group, RISC Conference room 3, 14:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt Wednesday 9th September 2015: Visit to Silchester Insula III, meet at Silchester car park 13:30 for a site visit at 14:00, organised by Trevor Coombs Saturday 19th September 2015 AGM and Lecture: Wiltshire’s secret underground city and Berkshire’s underground bunkers by Barrie Randall, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00 – see page 2 for details Wednesday 30th September 2015 Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group, RISC Conference room 3 14:00 to 16:00 Saturday 17th October 2015 Lecture: How did they make those beautiful things: metal working in Roman Britain by Justine Bayley, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00 Saturday 31st October 2015 Berkshire Historic Environment Forum Purley Barn, Purley 10:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt - see page 4 for details Wednesday 4th November 2015 Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group RISC Conference room 3 14:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt Saturday 21st November 2015 Lecture: Mesolithic and Paleolithic archaeology in the Kennet Valley by Cathie Barnett, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00: Wednesday 2nd December 2015 Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group RISC Conference room 3, 14:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt Saturday 12th December 2015 Lecture: Archaeology on holiday by BAS members, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00: From our Chairman Dear Members, I am happy to see that more and more members are joining the activities of the Society. -

Berkshire. Shaw-Cum-Donnington

DIRECTORY. J BERKSHIRE. SHAW-CUM-DONNINGTON. 225 Vaughan-Davies Mro.Sandhurst lodge Hanson Harry Richard, grocer Pitchell Hy. fly propr. College Twn (postal address, Wellington Col- Harper George Henry, cycle agent, Pitman Charles, news agent, York lege Station) York Town road Town road, College Town Wilkin George Frederick, The Hollies Harper Jn. stationer k sub-postmstr Pocock Richard, farm bailiff to J. C01.QIERCIAL. Hedges Geo. shopkpr. Lit. Sandhurst Over esq. Watts farm Aldworth Thomas, jobbing gardener, Hicks Henry, shopkpr. York Town rd Purvey William, Wellington Arms Branksome Hill road, College Town Hodge Waiter (Mrs.), laundry, York P.H. York Town road Allsworth Herbt. grocr.York Town rd Town road Rawlings George, chimney sweeper, Angel! Thomas & Son, tailors Hudson ArthurJas.grcr.College Town York Tow.u road Ankerson Richard, sbopkeeper,Brank-IHudson John, carrier, .A.lbion road Russell James M.D., C.M.AbeTd., some Hill road, College Town !Hunt Vincent,jobmastr.YorkTown rd M.R.C.S.Eng. surgoon, & medical Ayres Henry, market gardener James Edwd.Louis,drpr.YorkTown rd officer & public vaccinator, Sand- Barefoot Wm. Hy. White Swan P.H ~James William, grocer,York Town rd burst district, Easthampstead Bateman John, Rose & Crown P.H fJolly Claude, outfitter union, The Cedars Bedford James Sydney, hair dresser, Kent Fredk. Thos. baker,College Twn Sandhurst Working Men's Club(Jesse College Town Lark Frederick William, laundry, Weaver, manager) Blake Robt. Henry, Duke's Head P.H1 College road, College Town Saunders Harriett (Mrs.),sbopkeeper, Brake Charles John, land agent, York I Lockbart Robert llruce M. A. school- Branksome Hill road, College Town Town road, College Town master (boys' preparatory), Eagle Seeby Alfred, market gardener, Rose Brown Mary (Mrs.), draper, College School house dene, College Town . -

1 Conservation Casework Log Notes July 2020

CONSERVATION CASEWORK LOG NOTES JULY 2020 The GT conservation team received 191 new cases in England and three in Wales during June, in addition to ongoing work on previously logged cases. Written responses were submitted by the GT and/or CGTs for the following cases. In addition to the responses below, 60 ‘No Comment’ responses were lodged by the GT and/or CGTs. SITE COUNTY GT REF GRADE PROPOSAL WRITTEN RESPONSE ENGLAND Tyntesfield Avon E20/0350 II* PLANNING APPLICATION and CGT WRITTEN RESPONSE 10.07.2020 Listed Building Consent Proposed Thank you for consulting The Gardens Trust [GT] in its role as Statutory single-storey rear extension. Consultee with regard to the proposed development, which would Watercress Barn, Bristol Road, potentially affect the setting of the Tyntesfield Estate and its Grade II* Wraxall. BUILDING ALTERATION Registered Park & Garden. The Avon Gardens Trust is a member organisation of the GT and works in partnership with it in respect of the protection and conservation of registered sites, and is authorised by the GT to respond on GT’s behalf in respect of such consultations. Watercress Barn, a former agricultural building historically might have formed part of the Tyntesfield Estate but given the substantial separation distance to the main estate there is virtually no tangible relationship and limited visual connection with the Registered Park and Garden. Therefore, Avon Gardens Trust has no objection to this application. Yours sincerely, Ros Delany (Dr) Chairman, Avon Gardens Trust 1 Sandleford Priory Berkshire E20/0341 II PLANNING APPLICATION Outline CGT WRITTEN RESPONSE 22.07.2020 planning permission for up to Comments from Berkshire Gardens Trust 1,000 new homes; an 80 extra Thank you for consulting The Gardens Trust (GT) in its role as Statutory care housing units (Use Class C3) Consultee with regard to proposed Council strategies affecting sites listed as part of the affordable housing by Historic England (HE) on their Register of Parks and Gardens. -

Greenham and Crookham Plataeu

Greenham and Crookham Plataeu Encompasses the whole plateau from Brimpton to Greenham and the slopes along the Kennet Valley in the north and the River Enborne in the south and east. Includes some riverside land along the Enborne in the south, where the River forms the boundary. Extends west to include a group of woodlands at Sandleford. Joint Character Area: Thames Basin Heaths Geology: The plateau has a large area of Silchester Gravel the overlies London Clay Sand (Bagshot Beds) which is found in a band at the edge of the Gravel. There are also some areas of Head at the edge of the top of the plateau. The slopes are London Clay Formation clay, silt and sand. There is alluvium along the Enborne Valley. The western section has a similar geology with Silchester Gravel, London Clay Sand ad London Clay Formation. Topography: a flat plateau that slopes away to river valleys in the north, south and east. The western area is the south facing slope at the edge of the plateau as it extends westwards into the developed land at Wash Common. Biodiversity: · Heathland and acid grassland: Extensive heathland and acid grassland areas at Greenham Common with small areas at Bowdown Woods and remnants at the mainly wooded Crookham Common and at Greenham Golf Course. · Lowland Mixed Deciduous Woodland: Extensive areas on the plateau slopes. Bowdown Woods and the areas within Greenham Common SSSI. · Wet Woodland: found in the gullies on the slopes at the plateau edge. · Other habitat and species: farmland near Brimpton supports good populations of farmland birds. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

October 18 Tower.Pub

1 The Kingsclere Editors Mike Stokoe, Nicki Lee and Sarah Hewitt Advertising Les Wallace, Jada, Union Lane ( 298794 Tower Distribution Andrew Kitch ( 299743 Printer Kingsclere Design and Print Layout/Cover James Cruickshank "Use it or lose it" is a phrase we hear a lot in wildly differing circumstanc- es. It is so true for local village amenities and services. Over the years many shops, for example, have come and gone. Years ago Kingsclere had a bak- ery, ironmonger and quite a few more pubs than now. But custom de- clined and they disappeared. It's important to 'shop local' or we will find the option to do so is gone. Online shopping is helpful, but it's no good if you are in the middle of cooking and need an ingredient, or feel ill and need some medi- cine now, or professional advice on medications (see page 10 for a notice from our local chemist). Regularly shopping locally will make sure we have these last minute and emergency options available. Nicki Lee, October editor October 2018 Neither the Editor, nor the Management Committee accept responsibility for the opinions expressed or the goods and services advertised in the Kingsclere Tower magazine. To all “Tower” Contributors COPY FOR November to the editors at 3 Blue Meadow, Garrett Close [email protected] by October 12th Your Village Magazine Copy MUST include name, address/phone number 2 3 KINGSCLERE PARISH COUNCIL (KPC) Chairman: John Sawyer (297221) Clerk: Louise Porton (298634) email: [email protected] The result of the Parish Referendum held on 6th September was as fol- Office: 37 George Street, Kingsclere RG20 5NH lows: Public Opening: Mon & Wed 9:30-11:30am Electorate 2,630 Ripairian duties – This is the time of year when we need to think about the Number of votes cast 880 of which 255 were postal votes. -

1 Conservation Casework Log Notes February 2021

CONSERVATION CASEWORK LOG NOTES FEBRUARY 2021 The GT conservation team received 187 new cases for England in February, in addition to ongoing work on previously logged cases. Written responses were submitted by the GT and/or CGTs for the following cases. In addition to the responses below, 47 ‘No Comment’ responses were lodged by the GT and/or CGTs. SITE COUNTY GT REF GRADE PROPOSAL WRITTEN RESPONSE ENGLAND Moggerhanger Bedfordsh E20/1601 II PLANNING APPLICATION CGT WRITTEN RESPONSE 02.02.2021 Park ire Replacement of existing fence Thank you for bringing this application to the attention of the Gardens and hedgerow with new Trust, statutory consultee for applications affecting registered historic galvanised estate fencing 332.80 parks and gardens, and to Bedfordshire Gardens Trust. I am replying for metres long. New estate fencing both. will be installed 1.5 metres in We fully support these proposals, which have been under discussion for a front of retained historic while. As the applicant states, the removal of this length of somewhat hedgerow. Moggerhanger House, degraded 1960s hedging and chain link fencing, and its replacement with Park Road, Moggerhanger. stock-proof traditional estate fencing, will open up views across the North BOUNDARY Park towards Bottom Wood and the Avenue. This would be a welcome step in the restoration of the Reptonian historic parkland. Yours sincerely Bedfordshire Gardens Trust Conservation Sandleford Priory Berkshire E20/0341 II PLANNING APPLICATION Outline CGT WRITTEN RESPONSE 16.02.2021 planning permission for up to The Berkshire Gardens Trust, as an interested party, would like to make the 1,000 new homes; an 80 extra following submissions with regard to the care housing units (Use Class C3) above appeal which lies within the setting of Historic England’s Grade II 1 as part of the affordable housing Registered Park and Garden at Sandleford Priory provision; a new 2 form entry and the Grade I Sandleford Priory itself. -

West Berkshire Core Strategy Version for Adoption West Berkshire Council July 2012

West Berkshire Local Plan West Berkshire Core Strategy (2006-2026) Version for Adoption July 2012 West Berkshire Core Strategy Version for Adoption West Berkshire Council July 2012 West Berkshire Core Strategy Version for Adoption West Berkshire Council July 2012 West Berkshire Core Strategy Version for Adoption Contents Section 1 Introduction 5 What is the Core Strategy? 5 Section 2 Background and Challenges 6 Consultation 6 Relationship with Other Strategies 6 About West Berkshire 8 Cross Boundary Issues 9 Evidence Base 10 Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats 11 Content of the Core Strategy 14 Section 3 Shaping West Berkshire - Vision and Objectives 15 Spatial Vision 15 Strategic Objectives 16 Section 4 The Spatial Strategy 18 Introduction 18 Spatial Strategy 19 Newbury and Thatcham 24 Eastern Area 30 North Wessex Downs AONB 34 The East Kennet Valley 39 Section 5 Core Policies 42 Delivering New Homes and Retaining the Housing Stock 42 Newbury Racecourse Strategic Site Allocation 45 Sandleford Strategic Site Allocation 46 Housing Type and Mix 48 Infrastructure 50 Affordable Housing 51 Gypsies, Travellers and Travelling Showpeople 54 AWE Aldermaston and AWE Burghfield 56 Employment and the Economy 59 Town Centres 65 West Berkshire Core Strategy Version for Adoption West Berkshire Council July 2012 Contents Equestrian/Racehorse Industry 68 Transport 71 Design Principles 73 Sustainable Construction and Energy Efficiency 75 Flooding 77 Biodiversity 79 Green Infrastructure 83 Historic Environment and Landscape Character 85 Section -

Lecture on “Old Caversham”

LECTURE ON “OLD CAVERSHAM” BY MR. W. WING View of Caversham from Reading Abbey Reprinted from the Reading Mercury and Berks County Paper. The following Lecture on the History of Caversham from very early times was delivered by Mr. W. Wing in the National School-room, Caversham, on Monday evening, November 12th, 1894. The Rev. C. W. H. Kenrick, the Vicar, was in the chair. The Lecture was illustrated by a number of interesting relics, pictures, parochial documents, &c., and at the close General Radcliffe proposed, and Mr. D. Haslam seconded, a hearty vote of thanks to Mr. Wing for his very interesting and com- prehensive lecture. This version of Mr Wing’s work was transcribed from a printed copy of the lecture held by the Caversham branch of Reading Public Library (L 942.293). All of the text from the original work has been preserved but changes have been made in the formatting; short quotes have been italicised and street names have been put in the modern form. The spelling in the original document has been kept and so have the original para- graphs. Any illustrations were added by the modern-day editor, the original booklet contains none. The print in the original booklet is very small. It is hoped that as well as making the document more widely available this version will also be easier to read. 1 OLD CAVERSHAM HE PRESENT TIME seems particularly opportune for calling attention to the history of this parish, because with the end of the year a new depar- T ture takes place. -

Head of Games & PE

HEAD OF GAMES & PHYSICAL EDUCATION REQUIRED FROM SEPTEMBER 2019 The School St Gabriel’s is an independent forward thinking day school (GSA/IAPS) with traditional values. St Gabriel’s, founded in 1929, is for girls aged 6 months to 18 years and boys aged 6 months to 11 years. Our school is located in the spectacular setting of Sandleford Priory, to the south of Newbury, and occupies a beautiful Grade 1 listed building in 54 acres of parkland landscaped by "Capability" Brown, which provides a gracious setting in which to work. St Gabriel’s pupils thrive through strong, effective pastoral support; our broad curriculum and range of activities afford each pupil the opportunity to enjoy success according to their particular talents. St Gabriel’s is no ordinary school; parents are always impressed by the sense of purpose and enthusiasm of the talented, committed staff and the confidence of the extremely happy pupils. Our passionate staff deliver inspirational teaching and exceptional pastoral care creating a relaxed and friendly environment for learning. Pupils are provided with the opportunities to develop their confidence, talents and potential, enabling them to achieve high levels of success and readiness for the future. The Role The Head of Games & Physical Education will be an inspirational role model and an energetic, innovative teacher and passionate leader. They will create a dynamic programme which will encourage all pupils to strive earnestly, and some to excel. They will lead and develop a team of dedicated staff to create a culture of aspiration and engagement across the School. At the same time, they will have a rare ability to remain calm, efficient and smiling at the centre of a complex pattern of sporting activities. -

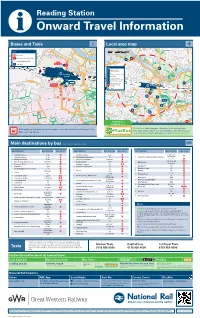

Reading Station I Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local Area Map

Reading Station i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map km 0 0.5 Caversham Key 0 Miles 0.25 A Bus Stop Rail replacement Bus Stop H RL Station Entrance/Exit North NA Taxi Rank Interchange Key 1 NE CM 0 m C Reading Crown Court in CM u Christchurch Meadows t e H Hotel s w Reading HX The Hexagon Theatre/Arts Centre a l KM Kings Meadow k Station i n L Reading Central Library g d i M Reading Museum & Town Hall s WS t RL Rivermead Leisure Complex a RailAir n c Coach Stop SC Oracle Shopping & Leisure e KM South West H Royal Berkshire Hospital SA EK EL Reading Station Interchange Cycle routes EM SB EO Footpaths EP SC H SD H FN M FE FC H C L H HX CW SC Reading is a H PlusBus area Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Rail replacement buses/coaches depart from the North Interchange (Stop PlusBus is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your ND) see map above. chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP SA EP 3, 3b, 9, 10, Arborfield Cross 3, 3b Mortimer Village 2, 2a SA 19a/19b/19c Arborfield Green 3, 3b SA { Northumberland Avenue 5+ SC { University of Reading (Main Campus) 21+, 21a EK { Basingstoke Road 6+, 6a SC { Palmer Park Stadium 4/X4, 17+ EO X38, X39, X40 EL NA { Bath Road (towards Calcot) jet black1