Lecture on “Old Caversham”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARCHAEOLOGY the Newsletter of the Berkshire Archaeological Society

ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Berkshire Archaeological Society Autumn 2015 Vol.17, No.3 Dates for your diary Wednesday 2nd September 2015: Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group, RISC Conference room 3, 14:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt Wednesday 9th September 2015: Visit to Silchester Insula III, meet at Silchester car park 13:30 for a site visit at 14:00, organised by Trevor Coombs Saturday 19th September 2015 AGM and Lecture: Wiltshire’s secret underground city and Berkshire’s underground bunkers by Barrie Randall, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00 – see page 2 for details Wednesday 30th September 2015 Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group, RISC Conference room 3 14:00 to 16:00 Saturday 17th October 2015 Lecture: How did they make those beautiful things: metal working in Roman Britain by Justine Bayley, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00 Saturday 31st October 2015 Berkshire Historic Environment Forum Purley Barn, Purley 10:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt - see page 4 for details Wednesday 4th November 2015 Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group RISC Conference room 3 14:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt Saturday 21st November 2015 Lecture: Mesolithic and Paleolithic archaeology in the Kennet Valley by Cathie Barnett, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00: Wednesday 2nd December 2015 Anglo-Saxon Discussion Group RISC Conference room 3, 14:00 to 16:00 organised by Andrew Hutt Saturday 12th December 2015 Lecture: Archaeology on holiday by BAS members, RISC Main Hall 14:00 to 16:00: From our Chairman Dear Members, I am happy to see that more and more members are joining the activities of the Society. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

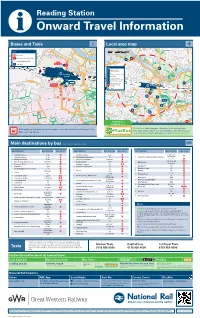

Reading Station I Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local Area Map

Reading Station i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map km 0 0.5 Caversham Key 0 Miles 0.25 A Bus Stop Rail replacement Bus Stop H RL Station Entrance/Exit North NA Taxi Rank Interchange Key 1 NE CM 0 m C Reading Crown Court in CM u Christchurch Meadows t e H Hotel s w Reading HX The Hexagon Theatre/Arts Centre a l KM Kings Meadow k Station i n L Reading Central Library g d i M Reading Museum & Town Hall s WS t RL Rivermead Leisure Complex a RailAir n c Coach Stop SC Oracle Shopping & Leisure e KM South West H Royal Berkshire Hospital SA EK EL Reading Station Interchange Cycle routes EM SB EO Footpaths EP SC H SD H FN M FE FC H C L H HX CW SC Reading is a H PlusBus area Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Rail replacement buses/coaches depart from the North Interchange (Stop PlusBus is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your ND) see map above. chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP SA EP 3, 3b, 9, 10, Arborfield Cross 3, 3b Mortimer Village 2, 2a SA 19a/19b/19c Arborfield Green 3, 3b SA { Northumberland Avenue 5+ SC { University of Reading (Main Campus) 21+, 21a EK { Basingstoke Road 6+, 6a SC { Palmer Park Stadium 4/X4, 17+ EO X38, X39, X40 EL NA { Bath Road (towards Calcot) jet black1 -

About the Property >> Summary | Heritage | Location | Transport | the Property | the Opportunity | Planning | Method of Sale | Contact

EXCEPTIONAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY www.cavershampark.co.uk Summary | Heritage | Location | Transport | The property | The opportunity | Planning | Method of sale | Contact Summary • Grade II listed manor house with stunning views across the Thames Valley • c115,000 sq ft (GIA) including ancillary buildings • Set in c93 acres of formal gardens and parkland • Less than 0.5 miles (5 min walk) to a wide range of local amenity, including supermarket, shops, restaurants and pubs • 2 miles from central Reading • Suitable for conversion to residential or a range of alternative uses (stpp) • Potential for new development within grounds (stpp) • For sale freehold with vacant possession Summary | Heritage | Location | Transport | The property | The opportunity | Planning | Method of sale | Contact Heritage EARLY PERIOD AND 18TH CENTURY 19TH – 20TH CENTURY BBC ACQUISITION MIDDLE AGES A £130,000 building programme was started The house burnt to the ground in 1850 and A fire caused serious damage to the roof in The site was established by the Anglo- in the early 18th century following the William was later re-built in a classical style around 1926 and following ongoing financial struggles, Saxons, who built the first manor house Cadogan’s purchase of the site. It was during an iron frame, designed by architect Horace and the outbreak of WWII, Caversham Park near Caversham Bridge. Following three this period Caversahm Park was arguably at Jones. This version of the manor house is what was sold to the BBC in 1941, when it became generations of Norman control, the site came its height with formal gardens, deer park and survives today (to varying degrees). -

Vebraalto.Com

7 Prospect Street, Caversham, Reading, RG4 8JB Tel: 0118 948 4040 Lowfield Road Caversham, Reading, Berkshire RG4 6NJ £1,150 PCM NEA LETTINGS: A detached house with a large kitchen/diner an enclosed garden, garage and private driveway in Caversham Park Village. The property has a large living room with French doors opening onto the garden and a large dual aspect kitchen/diner which overlooks the garden and has a doorway to a hall from which you can access the garage. Upstairs there is a very large master bedroom, another double bedroom off which there is a separate room which can be used for as a walk in wardrobe, study or small 3rd bedroom, there is a family bathroom with shower over bath. The property also benefits from a boarded loft with ample storage space, gas central heating and is double glazed throughout. It is situated with easy access to Reading Town Centre and Railway Station as well as Sonning and Henley-on-Thames. EPC Rating D. 7 Prospect Street, Caversham, Reading, RG4 8JB Tel: 0118 948 4040 Lowfield Road, Reading, Berkshire RG4 6NJ • Caversham Park Village • Detached House Master Bedroom 10'8" x 17'2" (3.27 x 5.25) • Unfurnished • Two Double Bedrooms plus a large storage room • Large kitchen/diner • Enclosed Garden • Garage and driveway parking • Council Tax Band E for 3 cars • EPC Rating D • Available 21st March Living Room 10'7" x 18'0" (3.23 x 5.49) A large dual aspect master bedroom with stripped wooden floors Bedroom Two 10'9" x 8'9" (3.29 x 2.69) A large dual aspect living room with stripped wooden floors and French -

Guide to School Records Reading

Guide to School Records Reading Cover illustration: A boy making a clay model of a spring flower at Redlands Infant School, c.1910-1911 (D/EX2134/2) Berkshire Record Office 9 Coley Avenue Reading RG1 6AF Tel 0118 937 5132 Fax 0118 937 5131 Email [email protected] www.berkshirerecordoffice.org.uk Using this Guide This is a guide to sources at the BRO for schools in the Reading area. It is arranged in alphabetical order of civil parish, and then by the different kinds of record available. The references after each entry should be quoted if you would like to see that item. For more information, please look up the reference in the appropriate catalogue. Please note that BRO does not hold individual pupil records or exam results. If you would like to visit the office to carry out research, please make an appointment. Please see our Planning Your Visit leaflet for more information. Note on Closure Access to documents containing personal information is usually restricted to a minimum of 50 years after the last entry in a document. If you wish to see a restricted item please ask a member of staff. Reading School Board/Education Authority general The majority of non-church schools were run by the Board, 1871-1903. From 1903 to 1974, the borough’s Education Committee was a Local Education Authority, independent of Berkshire County Council (see R/AC for minutes, R/FE for accounts, and R/E for other records.) Reading School Board Minutes 1871-1903 R/EB1/1-24 Reading Education Minutes 1903-1974 R/AC3 Authority Other records 1903-1974 R/E; R/FE Photograph -

Contents of the Old Redingensian Autumn 2011 Feature Writers in This Issue

THE Old Redingensian Autumn 2011 The old Redingensian Spring 2011 Contents of The Old Redingensian Autumn 2011 Page Front Cover 1 Contents 2 The President’s Letter 3 Notes and News 4 - 5 Enterprise Awards 6 - 8 The Royal Berkshire Regiment 9 Events 10 - 13 Forthcoming Events / Where Are They Now? 14 The Reading Old Boys Lodge Centenary Part 2 15 - 17 The Principal’s Letter / The Stevens’ Gift 18 The School Campaign for the 1125 fund 19 The New Refectory 20 School News 21 - 24 2011 – A Remarkable Cricket Season 25 For Valour 26 The Old School 27 - 30 Tea Trays Old and New 31 Sport 32 - 35 A Jog around Whiteknights 36 - 37 The Archive 38-39 Commentary 40 Overseas Branches 41 Obituaries 42 - 53 In Memoriam 54 From the Editors 55 Officers 2012 / Rear Cover 56 Feature Writers in this Issue The second article – following that in the Spring 2011 issue – commemorating the centenary this year of the Reading Old Boys’ Lodge is again written by His Honour Judge S O (Simon) Oliver (1969-76) pictured right, former Hon. Secretary of the Association (and former Master of the Lodge). Dr P P (Philip) Mortimer (1953-60), left, also contributes to the journal again, this time on pp 36-37. The Archivist provides the lead article pp 27-30. 2 The President’s Letter Returning to the topics in my Encouraging Personal last letter, much progress has Development In July four ORs been achieved, thanks to the held a Careers Day for Year many people involved. 12, aimed at helping boys with planning their futures. -

EXCEPTIONAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Www

EXCEPTIONAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY www.cavershampark.co.uk Summary | Heritage | Location | Transport | The property | The opportunity | Planning | Method of sale | Contact Summary • Grade II listed manor house with stunning views across the Thames Valley • c115,000 sq ft (GIA) including ancillary buildings • Set in c93 acres of formal gardens and parkland • Less than 0.5 miles (5 min walk) to a wide range of local amenity, including supermarket, shops, restaurants and pubs • 2 miles from central Reading • Suitable for conversion to residential or a range of alternative uses (stpp) • Potential for new development within grounds (stpp) • For sale freehold with vacant possession Summary | Heritage | Location | Transport | The property | The opportunity | Planning | Method of sale | Contact Heritage EARLY PERIOD AND 18TH CENTURY 19TH – 20TH CENTURY BBC ACQUISITION MIDDLE AGES A £130,000 building programme was started The house burnt to the ground in 1850 and A fire caused serious damage to the roof in The site was established by the Anglo- in the early 18th century following the William was later re-built in a classical style around 1926 and following ongoing financial struggles, Saxons, who built the first manor house Cadogan’s purchase of the site. It was during an iron frame, designed by architect Horace and the outbreak of WWII, Caversham Park near Caversham Bridge. Following three this period Caversahm Park was arguably at Jones. This version of the manor house is what was sold to the BBC in 1941, when it became generations of Norman control, the site came its height with formal gardens, deer park and survives today (to varying degrees). -

Vulnerability Brown Capability Brown Landscapes at Risk

Vulnerability Brown Capability Brown landscapes at risk A short report by the Gardens Trust Portrait of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, c.1770-75, Cosway, Richard (1742-1821) (Private Collection / Bridgeman Images) Cover image: aerial photograph of Moor Park, Hertfordshire, showing the impact of golf courses and parking on the Brown landscape. (© Historic England Archive 29859-031) Preface Following the 2016 Capability Brown Festival it is timely to reflect on the conservation challenges and opportunities facing the core of the collection of Brown’s` landscapes, which is unique to Britain and Ireland. As part of the Festival legacy the Gardens Trust (formerly the Garden History Society and Association of Gardens Trusts), with support from Historic England, has commissioned this review of the issues facing the survival of these landscapes as well as suggested solutions. The Gardens Trust was formed in 2015 from the merger of the Garden History Society and the Association of Gardens Trusts. It has inherited the GHS role as a national amenity society and a statutory consultee on planning applications affecting parks and gardens on the national Register of Parks and Gardens. It is also the umbrella group for the network of County Gardens Trusts in England and Wales and has a sister organisation in Scotland. Contents Introduction 3 The threats 5 Summary of threats 18 Recommendations 19 Further reading 20 This report was written by Dr Sarah Rutherford and Sarah Couch with guidance and input from the Gardens Trust. Both the authors are experienced landscape historians and have expertise in the conservation of historic landscapes and in the planning issues they face. -

Caversham (August 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Social Hist

VCH Oxfordshire • Texts in Progress • Caversham (August 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Social Hist. • p. 1 VCH Oxfordshire Texts in Progress Caversham Social History Social Character and Communal Life Caversham’s population was long split between the main settlements of Caversham and Lower Caversham in the south (which had ready access to the trading and social opportunities offered by neighbouring Reading), and the small scattered hamlets and farmsteads of the parish’s central and northern parts. Manor houses in the south-east (latterly in Caversham Park) were intermittently occupied by high-status resident lords from the Middle Ages onwards, but landownership became increasingly divided, and by the 18th century the riverside settlements were relatively ‘open’, with strong outside links and (by the 19th century) marked religious Nonconformity. Major residential development in the late 19th and early 20th century turned Caversham, Lower Caversham and (later) Emmer Green into suburbs of Reading both socially and administratively, while the northern upland areas remained rural. The Middle Ages During the Middle Ages Caversham manor was held by a succession of leading aristocrats of mainly comital rank and above, including the earls of Pembroke and Warwick. William Marshal (1146/7--1219), regent of England from 1216, chose Caversham as one of his main residences, and his generous endowment of the shrine and chapel there may have been part of a larger investment in the manor house, which stood close to the Thames.1 William kept a huntsman at Caversham,2 and either maintained or created the deer park, which was stocked with ten does in 1223.3 Free warren (the right to small game) was enjoyed as ‘of old’.4 Later lords maintained the house, which saw sporadic royal visits from Henry III,5 Edward I,6 and Edward II.7 Caversham was one of Margaret de Lacy’s regular residences 1 Above, landownership; for chapel, below, relig. -

Open Source Stupidity: the Threat to the BBC Monitoring Service

House of Commons Defence Committee Open Source Stupidity: The Threat to the BBC Monitoring Service Fifth Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 December 2016 HC 748 Published on 20 December 2016 by authority of the House of Commons The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Dr Julian Lewis MP (Conservative, New Forest East) (Chair) Douglas Chapman MP (Scottish National Party, Dunfermline and West Fife) James Gray MP (Conservative, North Wiltshire) Jack Lopresti MP (Conservative, Filton and Bradley Stoke) Johnny Mercer MP (Conservative, Plymouth, Moor View) Mrs Madeleine Moon MP (Labour, Bridgend) Gavin Robinson MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Belfast East) Ruth Smeeth MP (Labour, Stoke-on-Trent North) John Spellar MP (Labour, Warley) Bob Stewart MP (Conservative, Beckenham) Phil Wilson MP (Labour, Sedgefield) The following were Members of the Committee during the course of the inquiry: Jim Shannon MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Strangford) Richard Benyon MP (Conservative, Newbury) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in the House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this Report is published on the relevant inquiry page of the Committee’s website. -

Caversham (August 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Landownership • P

VCH Oxfordshire • Texts in Progress • Caversham (August 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Landownership • p. 1 VCH Oxfordshire Texts in Progress Caversham Landownership For much of its history Caversham was divided between a single large manor (assessed in 1086 at 20 hides), and several smaller estates including some of medieval origin. Until the mid 12th century the manor almost certainly included land in nearby Shiplake,1 and it seems possible that it originally comprised an even larger area from which Eye and Dunsden was separated following the grant of Sonning (Berks.) to the bishop of Sherborne and Ramsbury in the later Anglo-Saxon period.2 During the Middle Ages it was held by a succession of high-status lords for whom it supplied a base in the Thames Valley within convenient reach of London. Sales of land reduced its extent in the 17th century, but it continued to be held by wealthy owners who successively rebuilt the mansion house in Caversham park. The estate was finally broken up in the early 1920s. An early estate at Cane End belonged to Notley abbey (Bucks.), and in the 16th century was regarded as a manor. The abbey also owned the valuable rectory estate (comprising tithes and glebe), which at the Reformation passed to Christ Church, Oxford. Several small to medium-sized estates of up to 500 a. were created from the 17th century, partly from land sold by the lords of Caversham. Caversham Manor Descent to c.1600 In 1066 Caversham was held freely by a thegn called Swein, and in 1086 by the Norman tenant-in-chief Walter Giffard.3 The Giffard family’s English seat was Long Crendon (Bucks.),4 but probably they maintained a house at Caversham, which was the only Oxfordshire estate they kept in hand.