Relationships with Jewellery?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application of Jingchu Cultural Symbol in Design of Turquoise Jewelry

2020 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Social Sciences & Humanities (SOSHU 2020) Application of Jingchu Cultural Symbol in Design of Turquoise Jewelry Wang Xiaoyue Department of Jewelry, College of Jewelry, China Univercity of Geosciences, Wuhan, Hubei, 430074, China email: [email protected] Keywords: Jingchu Cultural Symbol, Turquoise, Jewelry Design, Connotation Features, Chutian God Bird, Creative Expression Abstract: Turquoise is one of the four famous jades in China, which carries the Chinese jade culture for thousands of years. Jingchu culture is a strong local culture represented by the Hubei region of our country. It has a long history and is an important branch of the splendid local history and culture in our country. The combination of Jingchu cultural symbols and turquoise culture to create jewelry has a long history. This paper discusses the application of Hubei Jingchu cultural symbol in the design of turquoise jewelry under the guidance of these two cultural contents. 1. Jingchu Culture Symbol and Turquoise Culture Jingchu culture is the representative of the local culture of our country. It is a special cultural content formed in a specific historical period and a specific region. At that time, in order to inherit the cultural content of Chinese vinegar, carry forward the long history, integrate the Jingchu culture into many treasure jewelry, and form the characteristic jewelry type with the cultural symbol of Jingchu as the background, it is the turquoise jewelry which combines the Jingchu culture. Turquoise, as one of the four great jades in China, has a profound cultural background which can not be underestimated. 1.1. Jingchu Culture and Its Symbols The culture of jingchu is named after the state of chu and the people of chu. -

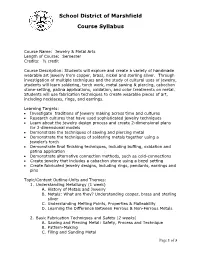

School District of Marshfield Course Syllabus

School District of Marshfield Course Syllabus Course Name: Jewelry & Metal Arts Length of Course: Semester Credits: ½ credit Course Description: Students will explore and create a variety of handmade wearable art jewelry from copper, brass, nickel and sterling silver. Through investigation of multiple techniques and the study of cultural uses of jewelry, students will learn soldering, torch work, metal sawing & piercing, cabochon stone-setting, patina applications, oxidation, and color treatments on metal. Students will use fabrication techniques to create wearable pieces of art, including necklaces, rings, and earrings. Learning Targets: Investigate traditions of jewelry making across time and cultures Research cultures that have used sophisticated jewelry techniques Learn about the jewelry design process and create 2-dimensional plans for 3-dimensional models Demonstrate the techniques of sawing and piercing metal Demonstrate the techniques of soldering metals together using a jeweler’s torch Demonstrate final finishing techniques, including buffing, oxidation and patina application Demonstrate alternative connection methods, such as cold-connections Create jewelry that includes a cabachon stone using a bezel setting Create fabricated jewelry designs, including rings, pendants, earrings and pins Topic/Content Outline-Units and Themes: 1. Understanding Metallurgy (1 week) A. History of Metals and Jewelry B. Metals: What are they? Understanding copper, brass and sterling silver C. Understanding Melting Points, Properties & Malleability D. Learning the Difference Between Ferrous & Non-Ferrous Metals 2. Basic Fabrication Techniques and Safety (2 weeks) A. Sawing and Piercing Metal: Safety, Process and Technique B. Pattern-Making C. Filing and Sanding Metal Page 1 of 3 D. Creating Texture: Hammering, Stamping, Embossing, Chasing E. -

Newsletter/Fall 2016 the DAS DAS the Decorative Arts Society, Inc

newsletter/fall 2016 Volume 24, Number 2 Decorative Arts Society The DAS DAS The Decorative Arts Society, Inc. in 1990 for the encouragement of interest in, the appreciation of and the exchange of information about the decorative arts. To, is pursuea not-for-profit its purposes, New theYork DAS corporation sponsors foundedmeetings, Newsletter programs, seminars, tours and a newsletter on the decorative arts. Its supporters include museum curators, academics, collectors and dealers. Please send change-of-address information by e-mail to [email protected]. Board of Directors Editor President Gerald W. R. Ward Gerald W. R. Ward Senior Consulting Curator & Susan P. Schoelwer Senior Consulting Curator Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator Robert H. Smith Senior Curator Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of of American Decorative Arts and George Washington’s Mount Vernon American Decorative Arts and Sculpture Emeritus Mount Vernon, VA Sculpture Emeritus Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Boston, MA Boston, MA Treasurer Stewart G. Rosenblum, Esq. Robert C. Smith Award Committee Coordinator Jeannine Falino, Chair Ruth E. Thaler-Carter Secretary Independent Curator Freelance Writer/Editor Moira Gallagher New York, NY Rochester, NY Research Assistant Metropolitan Museum of Art Lynne Bassett New York, NY Costume and Textile Historian Program Chairperson Dennis Carr Emily Orr Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of The DAS Newsletter is a publication Assistant Curator of Modern and American Decorative Arts and of the Decorative Arts Society, Inc. The Contemporary American Design Sculpture purpose of the DAS Newsletter is to serve as Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA a forum for communication about research, Museum Boston, MA exhibitions, publications, conferences and New York, NY other activities pertinent to the serious Emily Orr study of international and American deco- Margaret Caldwell Assistant Curator of Modern and rative arts. -

Important Jewelry

IMPORTANT JEWELRY Tuesday, October 16, 2018 NEW YORK IMPORTANT JEWELRY AUCTION Tuesday, October 16, 2018 at 10am EXHIBITION Friday, October 12, 10am – 5pm Saturday, October 13, 10am – 5pm Sunday, October 14, Noon – 5pm Monday, October 15, 10am – 2pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Lot 27 INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATES OF Henri Jo Barth The Noel and Harriette Levine Collection A Long Island Lady A Distinguished New Jersey Interior Decorator A New York Lady A New York Private Collector Barbara Wainscott INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Florida Lady A Miami Lady A New Jersey Private Collector A New York Collector A Private Collection A Private Collector CONTENTS Important Jewelry 1-535 Glossary I Conditions of Sale II Terms of Guarantee IV Information on Sales & Use Tax V Buying at Doyle VI Selling at Doyle VIII Auction Schedule IX Company Directory X Absentee Bid Form XII Lot 529 The Estate of Henri Jo ‘Bootsie’ Barth Doyle is honored to auction jewelry from the Estate of Henrie Jo “Bootsie” Barth. Descended from one of Shreveport, Louisiana’s founding families, Henrie Jo Barth, known all her life as Bootsie, was educated at The Hockaday School in Dallas and Bryn Mawr College. She settled on New York’s Upper East Side and maintained close ties with Shreveport, where she had a second residence for many years. Bootsie was passionate about travel and frequently left her Manhattan home for destinations around the world. One month of every year was spent traveling throughout Europe with Paris as her Lots 533 & 535 base and another month was spent in Japan, based in Kyoto. -

Important Jewelry

IMPORTANT JEWELRY Wednesday, October 18, 2017 NEW YORK IMPORTANT JEWELRY AUCTION Wednesday, October 18, 2017 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, October 14, 10am – 5pm Sunday, October 15, Noon – 5pm Monday, October 16, 10am – 5pm Tuesday, October 17, 10am – 2pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $45 INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM CONTENTS THE ESTATES OF Important Jewelry 1-519 Conditions of Sale I Emmajane DeLong Terms of Guarantee III Geraldine Hickox Information on Sales & Use Tax IV Barbara Hartley Lord Buying at Doyle V Aileen Mehle Selling at Doyle VII A New York City Private Estate Auction Schedule VIII Company Directory IX Absentee Bid Form XI INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Beverly Hills Collector A Connecticut Collector A Distinguished Lady A Lady A Pennsylvania Collector A Family of Spanish Descent Lot 519 5 3 1 2 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 Pair of Gold, Cabochon Peridot and High Karat Gold and Emerald Pair of High Karat Gold Earclips, Zolotas Gold ‘Mycenaean’ Necklace, Ilias Lalaounis Gold ‘Mycenaean’ Bracelet, Ilias Lalaounis Aquamarine and Mother-of-Pearl Earclips, Bangle Bracelet 22 kt., composed of hammered gold 18 kt., composed of pairs of scrolled links on 18 kt., composed of pairs of scrolled Elizabeth Locke 22 kt., the tubular bangle of polished twisted overlapping elongated oval bombé panels, a double strand mesh gold chain, links, no. F69, with maker’s mark, model 18 kt., the oval hammered gold stepped gold spaced by slender rope-twist bands, signed Zolotas, with maker’s mark, with maker’s mark, approximately 63 dwts. -

Jennifer Shaifer Thesis

50 specialized in the lost-wax casting method to create his work and even wrote a textbook on the subject.113 Winston influenced the work of MAG members Robert Dhaemers, Florence Resnikoff, and Irena Brynner, among others. Robert Dhaemers utilized techniques and surface treatments such as patinas and engraving to give his jewelry a worn appearance. He didn’t believe in the “artificial maintenance” of keeping jewelry polished.114 Florence Resnikoff’s jewelry showcased her interest in color and metallurgy. She utilized several techniques to achieve her designs including casting, enameling, electroforming, and anodization of refractory metals.115 Franz Bergmann, an immigrant from Vienna, was one of the few jewelers in San Francisco who maintained an atelier. He forged wire and cut sheets to produce his works with a constructivist and/or surrealist designs.116 Irena Brynner, who apprenticed with Bergmann briefly, looked at jewelry as sculpture and applied techniques such as forging and piercing to realize her designs. Her later works simulated the appearance of the lost-wax casting techniques; however, she developed a new aesthetic using a tool called a water welder.117 Peter Macchiarini, another studio/shop owner, incorporated ideas of constructivism and anthropomorphism in his designs. His designs showcased internal structures with the use of patinas as well as found objects.118 Merry Renk replicated the geometric abstract structures found in nature. Her early works were nonobjective designs that emphasized the potential of metal by using interlocking forms, metal folding, and enamel. As she developed her design philosophy, she progressed into more realistic and less abstract forms. -

A Conversation with Metalsmith Cynthia Eid

artist profile A conversation with metalsmith Cynthia Eid Educator, author, and artist another piece, the better I like it. One of the most satisfying things Cynthia Eid is known for her about deep-drawing is turning the metal inside out. Metal is so stiff, but there are times when you can watch it flow like taffy. bold, adventurous forms that test the limits of metal’s structure. After getting your degree, you spent five years doing bench Twisted, but never tortured, her work. How necessary was that kind of training? On the one hand, I learned all sorts of things that I didn’t learn at pieces evoke the natural world the university. I learned to think faster, design faster, and work as seen through a dreamscape — faster. I learned a lot of technical stuff. But I also made a lot of ugly half-imagined versions of familiar stuff in the gold-jewelry factory where I worked for 3 years, and that was painful. So, I took pride in making the best hinges, organic forms. Eid is based in settings, molds, and box catches I could. Lexington, Massachusetts, teaches at workshops across the country, and has become known for her technical Any advice for jewelers just starting out? Make yourself rounded. There’s a lot to be said for knowing how expertise in new tools and materials, including Argentium Sterling Silver. [a] Sampler brooch. Sterling silver, 14k gold. 2¾ x 1¼ x ¼ in. (70 x 32 x 6.5mm). [b] Torsion pendant on handwoven chain. Sterling Your family was important in your becoming an artist, because silver, 14k and 18k gold, amethyst, pearls. -

Note This List Is NOT 100% Correct

Note this list is NOT 100% Correct Ref Value product_name main_category 151 299 (1 Year Warranty) Suntaiho Quick Charging 3A USB Magnetic Charger Cable Mobiles & Accessories USB/Type C/iPhone Micro Cable 151 284 (COD) 9 Colors TWS Bluetooth Earphone inpods TWS i12 Earbuds Sports Airpod Mobiles & Accessories Headsets Wireless HiFi Colorful Headphone For iPhone and Android 151 448 (COD) 9 Colors TWS Bluetooth Earphone inpods TWS i12 Earbuds Sports Airpod Mobiles & Accessories Headsets Wireless HiFi Colorful Headphone For iPhone and Android 151 284 (COD) 9 Colors TWS Bluetooth Earphone inpods TWS i12 Earbuds Sports Airpod Mobiles & Accessories Headsets Wireless HiFi Colorful Headphone For iPhone and Android 151 364 **Antique Carved Wood Hand Crank Music Box Birthday Gifts Musical Box Toys, Games & Collectibles 151 338 [NNJXD]Baby Girl Dress Kids Dresses for Girls Christmas Party Santa Tulle Babies & Kids Princess Ball Gown 151 617 [NNJXD]Baby Girl Dress Lace Princess Girls Clothes Birthday Party Little Ball Kids Babies & Kids Clothes 151 200 [Seller Recommend] 3 Colors 1A 24V 8mm Mini IP 65 Waterproof Shock-proof Motors Car Momentary Push Button Power Switch Zi 151 534 [Spot] USB Flash Drive Metal With Customizable Logo Pen Drive Flash Stick For Laptops & Computers Portable Computer USB 2.0 32GB 16GB 8GB 4GB 2GB 1GB 151 341 【COD & Ready stock】Korean Skirt Women Elegant Plaid High Waist Skirts Women's Apparel denim skirt High waist skirt palda mini skirt 151 278 【COD】 Women Messenger Crossbody Bag Wallet Handbag Phone Pouch Women's Bags Case -

2017 Workshops Springs

Eureka 2017 Workshops Springs School of The Arts ESSA-ART.ORG 1 From our executive director Dear ESSA friends, When I first started working as ESSA’s Executive Director ten years ago, we had one building that served all needs…workshop space, ad- ministrative office, and dining area. All of our wood workshops were held at another location in town and when we started offering blacksmith- ing and metal fabrication workshops, we held them outside behind our main building that was nestled on less than an acre of land. Today, we have a 55 acre campus and our latest addition of a woodworking studio gives us the balance we’ve been dreaming about for years. We now Table of Contents have studio space for painting and drawing, clay building and throwing, jewelry making and the creation of small metal objects, blacksmithing and metal fabricating, weaving and working Workshop Info...........................................3 Master Schedule....................................4-5 with textiles, leather crafting, and now…wood turning and wood working. I hope you will help Youth Art Week...........................................5 us spread the word that the Eureka Springs School of the Arts is a full-blown campus offering a Workshops by Medium variety of workshops to meet a broad spectrum of creative needs! Painting & Drawing................................6-9 Small Metals......................................10-12 Sincerely, Clay...................................................12-13 Peggy Kjelgaard, Ph.D. Iron....................................................14-15 Executive Director Wood................................................16-18 Glass......................................................19 Textiles................................................20-21 Leather...............................................21-22 Special Media....................................22-23 Support for ESSA is provided, in part, by the Arkansas Arts Council, an agency of the Department of Arkansas Heritage and the National Endowment for the Arts. -

CHARON KRANSEN ARTS 817 WEST END AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10025 USA PHONE: 212 627 5073 FAX: 212 663 9026 EMAIL: [email protected]

CHARON KRANSEN ARTS 817 WEST END AVENUE NEW YORK NY 10025 USA PHONE: 212 627 5073 FAX: 212 663 9026 EMAIL: [email protected] www.charonkransenarts.com SEP. 2019 A JEWELER’S GUIDE TO APPRENTICESHIPS: HOW TO CREATE EFFECTIVE PROGRAMS suitable for shop owners, students as well as instructors, the 208 page volume provides detailed, proven approaches for finding , training and retaining valuable employees. it features insights into all aspects of setting up an apprenticeship program, from preparing a shop and choosing the best candidates to training the apprentice in a variety of common shop procedures. an mjsa publication. $ 29.50 ABSOLUTE BEAUTY – 2007catalog of the silver competition in legnica poland, with international participants. the gallery has specialized for 30 years in promoting contemporary jewelry. 118 pages. full color. in english. $ 30.00 ADDENDA 2 1999- catalog of the international art symposium in norway in 1999 in which invited international jewelers worked with jewelry as an art object related to the body. in english. 58 pages. full color. $ 20.00 ADORN – NEW JEWELLERY - this showcase of new jewelry offers a global view of exciting work from nearly 200 cutting-edge jewelry designers. it highlights the diverse forms that contemporary jewelry takes, from simple rings to elaborate body jewelry that blurs the boundaries between art and adornment. 460 color illustrations. 272 pages. in english. $ 35.00 ADORNED – TRADITIONAL JEWELRY AND BODY DECORATION FROM AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC adorned draws on the internationally recognised ethnographic collection of the macleay museum at the university of sidney and the collections of individual members of the oceanic art society of australia. -

New Designers Birmingham School of Jewellery Junk: Rubbish Into Gold

The Magazine of the Association for Contemporary Jewellery £4.95 findings Free to members Issue 61 Autumn 2015 New Designers Birmingham School of Jewellery Junk: Rubbish into Gold Technical Update: CAD A Year of Development Artists in Conversation Mima Jewellery Symposium Alexander McQueen at the V&A A Sense of Jewellery Shelanu Women’s Craft Collective ISSN 2041-7047 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN There is, for me, a feeling that summer and autumn are rela- FINDINGS Autumn 2015 tively relaxed periods in the year: various graduation shows and Autumn Fairs to be taken in, as well as holidays and amenable weather to be enjoyed. For many members however 2 Letter from the Chairman it has to be a productive period in preparation for the really and Editor serious Christmas offensive. There are several aspects to this but I do think it amazing (and unfortunate?) that so many 3 New Designers makers and retailers still have to be frantic in December and 5 Birmingham School of under-employed in January! Interesting stuff in November includes the last leg of our Jewellery is 125! ‘Sleight of Hand’ exhibition showing in Plymouth. On behalf of the Association 6 Junk: Rubbish into Gold I would like to thank all exhibitors and those who have enabled it to tour to an impressive 3 venues. I’m particularly pleased that our exhibitors included two 7 Technical Update: CAD members from Australia and one from Vienna. Corporate, as well as personal best wishes to our members and friends who 10 Work Experience are involved in the following recent developments: the new National Association of Jewellers, comprising the former B.J.A. -

Why Should Jewellers Care About the “Digital” ?

Why Should Jewellers Care About The “Digital” ? KOULIDOU, Konstantia Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/27954/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version KOULIDOU, Konstantia (2018). Why Should Jewellers Care About The “Digital” ? Journal of Jewellery Research, 1. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk WHY SHOULD JEWELLLERS CARE ABOUT THE DIGITAL? AUTHOR Nantia Koulidou Journal of Jewellery Research - Volume 01 - February 2018 17 Why should jewellers care about the Digital? ABSTRACT The widespread development of technological components knowledge on the history and role of jewellery in peoples’ that could be miniaturised and worn on the body has opened lives. The functions of jewellery pieces are often rooted new possibilities for jewellers to explore the intersection in rituals and ceremonial activities, in personal values and of jewellery practices and the capabilities of digital adornment, the supernatural power of jewellery to connect technologies. Increasingly jewellery can play a role in valuing people with others in different spaces and time and the close the body, understanding, amplifying and highlighting the relationship between jewellery and body (Besten, 2011; body. However, this area remains under-explored within the Cheung, 2006; Dormer, 1994). These aspects have often contemporary jewellery practice. been neglected by big corporates. Either for sports, medical This paper provides a critical review of digital purposes or high-tech special effects in the catwalk, the jewellery practice from a jeweller’s perspective and offers body is often understood as data that can be tracked and the grounding for a framework for understanding digital manipulated and jewellery as a convenient place to host jewellery that reveals its potential within people’s lives.