Jennifer Shaifer Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application of Jingchu Cultural Symbol in Design of Turquoise Jewelry

2020 3rd International Conference on Interdisciplinary Social Sciences & Humanities (SOSHU 2020) Application of Jingchu Cultural Symbol in Design of Turquoise Jewelry Wang Xiaoyue Department of Jewelry, College of Jewelry, China Univercity of Geosciences, Wuhan, Hubei, 430074, China email: [email protected] Keywords: Jingchu Cultural Symbol, Turquoise, Jewelry Design, Connotation Features, Chutian God Bird, Creative Expression Abstract: Turquoise is one of the four famous jades in China, which carries the Chinese jade culture for thousands of years. Jingchu culture is a strong local culture represented by the Hubei region of our country. It has a long history and is an important branch of the splendid local history and culture in our country. The combination of Jingchu cultural symbols and turquoise culture to create jewelry has a long history. This paper discusses the application of Hubei Jingchu cultural symbol in the design of turquoise jewelry under the guidance of these two cultural contents. 1. Jingchu Culture Symbol and Turquoise Culture Jingchu culture is the representative of the local culture of our country. It is a special cultural content formed in a specific historical period and a specific region. At that time, in order to inherit the cultural content of Chinese vinegar, carry forward the long history, integrate the Jingchu culture into many treasure jewelry, and form the characteristic jewelry type with the cultural symbol of Jingchu as the background, it is the turquoise jewelry which combines the Jingchu culture. Turquoise, as one of the four great jades in China, has a profound cultural background which can not be underestimated. 1.1. Jingchu Culture and Its Symbols The culture of jingchu is named after the state of chu and the people of chu. -

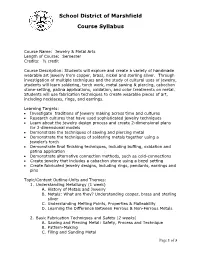

School District of Marshfield Course Syllabus

School District of Marshfield Course Syllabus Course Name: Jewelry & Metal Arts Length of Course: Semester Credits: ½ credit Course Description: Students will explore and create a variety of handmade wearable art jewelry from copper, brass, nickel and sterling silver. Through investigation of multiple techniques and the study of cultural uses of jewelry, students will learn soldering, torch work, metal sawing & piercing, cabochon stone-setting, patina applications, oxidation, and color treatments on metal. Students will use fabrication techniques to create wearable pieces of art, including necklaces, rings, and earrings. Learning Targets: Investigate traditions of jewelry making across time and cultures Research cultures that have used sophisticated jewelry techniques Learn about the jewelry design process and create 2-dimensional plans for 3-dimensional models Demonstrate the techniques of sawing and piercing metal Demonstrate the techniques of soldering metals together using a jeweler’s torch Demonstrate final finishing techniques, including buffing, oxidation and patina application Demonstrate alternative connection methods, such as cold-connections Create jewelry that includes a cabachon stone using a bezel setting Create fabricated jewelry designs, including rings, pendants, earrings and pins Topic/Content Outline-Units and Themes: 1. Understanding Metallurgy (1 week) A. History of Metals and Jewelry B. Metals: What are they? Understanding copper, brass and sterling silver C. Understanding Melting Points, Properties & Malleability D. Learning the Difference Between Ferrous & Non-Ferrous Metals 2. Basic Fabrication Techniques and Safety (2 weeks) A. Sawing and Piercing Metal: Safety, Process and Technique B. Pattern-Making C. Filing and Sanding Metal Page 1 of 3 D. Creating Texture: Hammering, Stamping, Embossing, Chasing E. -

Community, Identity, and Spatial Politics in San Francisco Public Housing, 1938--2000

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2005 "More than shelter": Community, identity, and spatial politics in San Francisco public housing, 1938--2000 Amy L. Howard College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, United States History Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Howard, Amy L., ""More than shelter": Community, identity, and spatial politics in San Francisco public housing, 1938--2000" (2005). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623466. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7ze6-hz66 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. Furtherowner. reproduction Further reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. “MORE THAN SHELTER”: Community, Identity, and Spatial Politics in San Francisco Public Housing, 1938-2000 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amy Lynne Howard 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Newsletter/Fall 2016 the DAS DAS the Decorative Arts Society, Inc

newsletter/fall 2016 Volume 24, Number 2 Decorative Arts Society The DAS DAS The Decorative Arts Society, Inc. in 1990 for the encouragement of interest in, the appreciation of and the exchange of information about the decorative arts. To, is pursuea not-for-profit its purposes, New theYork DAS corporation sponsors foundedmeetings, Newsletter programs, seminars, tours and a newsletter on the decorative arts. Its supporters include museum curators, academics, collectors and dealers. Please send change-of-address information by e-mail to [email protected]. Board of Directors Editor President Gerald W. R. Ward Gerald W. R. Ward Senior Consulting Curator & Susan P. Schoelwer Senior Consulting Curator Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator Robert H. Smith Senior Curator Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of of American Decorative Arts and George Washington’s Mount Vernon American Decorative Arts and Sculpture Emeritus Mount Vernon, VA Sculpture Emeritus Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Boston, MA Boston, MA Treasurer Stewart G. Rosenblum, Esq. Robert C. Smith Award Committee Coordinator Jeannine Falino, Chair Ruth E. Thaler-Carter Secretary Independent Curator Freelance Writer/Editor Moira Gallagher New York, NY Rochester, NY Research Assistant Metropolitan Museum of Art Lynne Bassett New York, NY Costume and Textile Historian Program Chairperson Dennis Carr Emily Orr Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of The DAS Newsletter is a publication Assistant Curator of Modern and American Decorative Arts and of the Decorative Arts Society, Inc. The Contemporary American Design Sculpture purpose of the DAS Newsletter is to serve as Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA a forum for communication about research, Museum Boston, MA exhibitions, publications, conferences and New York, NY other activities pertinent to the serious Emily Orr study of international and American deco- Margaret Caldwell Assistant Curator of Modern and rative arts. -

Important Jewelry

IMPORTANT JEWELRY Tuesday, October 16, 2018 NEW YORK IMPORTANT JEWELRY AUCTION Tuesday, October 16, 2018 at 10am EXHIBITION Friday, October 12, 10am – 5pm Saturday, October 13, 10am – 5pm Sunday, October 14, Noon – 5pm Monday, October 15, 10am – 2pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Lot 27 INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATES OF Henri Jo Barth The Noel and Harriette Levine Collection A Long Island Lady A Distinguished New Jersey Interior Decorator A New York Lady A New York Private Collector Barbara Wainscott INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Florida Lady A Miami Lady A New Jersey Private Collector A New York Collector A Private Collection A Private Collector CONTENTS Important Jewelry 1-535 Glossary I Conditions of Sale II Terms of Guarantee IV Information on Sales & Use Tax V Buying at Doyle VI Selling at Doyle VIII Auction Schedule IX Company Directory X Absentee Bid Form XII Lot 529 The Estate of Henri Jo ‘Bootsie’ Barth Doyle is honored to auction jewelry from the Estate of Henrie Jo “Bootsie” Barth. Descended from one of Shreveport, Louisiana’s founding families, Henrie Jo Barth, known all her life as Bootsie, was educated at The Hockaday School in Dallas and Bryn Mawr College. She settled on New York’s Upper East Side and maintained close ties with Shreveport, where she had a second residence for many years. Bootsie was passionate about travel and frequently left her Manhattan home for destinations around the world. One month of every year was spent traveling throughout Europe with Paris as her Lots 533 & 535 base and another month was spent in Japan, based in Kyoto. -

The Forming of the Metal Arts Guild, San Francisco (1929-1964)

Metal Rising: The Forming of the Metal Arts Guild, San Francisco (1929-1964) Jennifer Shaifer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master’s of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts. The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2011 © 2011 Jennifer Shaifer All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is a project I hold dear to my heart. A milestone in my life in which I will never forget. My research started as a journey across the United States to tell a story about the formation of the Metal Arts Guild, but has ended with a discovery about the strength of the human spirit. I was not fortunate to meet many of the founding members of the Metal Arts Guild, but my research into the lives and careers of Margaret De Patta, Irena Brynner, and Peter Macchiarini has provided me with invaluable inspiration. Despite the adversity these artists faced, their strength still reverberates through the trails of history they left behind for an emerging scholar like me. Throughout this project, I have received so much support. I would like to thank Heidi Nasstrom Evans, my thesis advisor, for her encouragement and patience during the thesis writing process. It was during her Spring 2007 class on modernism, that I was introduced to a whole new world of art history. I also want to thank Cynthia Williams and Peggy Newman for their constant source of support. A huge thank you to Alison Antleman and Rebecca Deans for giving me access to MAG’s archives and allowing me to tell their organization’s story. -

Ruth Asawa Bibliography

STANFORD UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, DEPARTMENT OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Ruth Asawa Bibliography Articles, periodicals, and other printed works in chronological order, 1948-2014, followed by bibliographic citations in alphabetical order by author, 1966-2013. Listing is based on clipping files in the Ruth Asawa papers, M1585. 1948 “Tomorrow’s Artists.” Time Magazine August 16, 1948. p.43-44 [Addison Gallery review] [photocopy only] 1952 “How Money Talks This Spring: Shortest Jacket-Longest Run For Your Money.” Vogue February 15, 1952 p.54 [fashion spread with wire sculpture props] [unknown article] Interiors March 1952. p.112-115 [citation only] Lavern Originals showroom brochure. Reprinted from Interiors, March 1952. Whitney Publications, Inc. Photographs of wire sculptures by Alexandre Georges and Joy A. Ross [brochure and clipping with note: “this is the one Stanley Jordan preferred.”] “Home Furnishings Keyed to ‘Fashion.’” New York Times June 17, 1952 [mentions “Alphabet” fabric design] [photocopy only] “Bedding Making High-Fashion News at Englander Quarters.” Retailing Daily June 23, 1952 [mentions “Alphabet” fabric design] [photocopy only] “Predesigned to Fit A Trend.” Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. p.148-159. With photographs of Asawa’s “Alphabet” fabric design on couch, chair, lamp, drapes, etc., and Graduated Circles design by Albert Lanier. All credited to designer Everett Brown “Living Around The Clock with Englander.” Englander advertisement. Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. p.28-29 [“The ‘Foldaway Deluxe’ bed comes only in Alphabet pattern, black and white.”] “What’s Ticking?” Golding Bros. Company, Inc. advertisement. Living For Young Homemakers Vol.5 No.10 October 1952. -

Important Jewelry

IMPORTANT JEWELRY Wednesday, October 18, 2017 NEW YORK IMPORTANT JEWELRY AUCTION Wednesday, October 18, 2017 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, October 14, 10am – 5pm Sunday, October 15, Noon – 5pm Monday, October 16, 10am – 5pm Tuesday, October 17, 10am – 2pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $45 INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM CONTENTS THE ESTATES OF Important Jewelry 1-519 Conditions of Sale I Emmajane DeLong Terms of Guarantee III Geraldine Hickox Information on Sales & Use Tax IV Barbara Hartley Lord Buying at Doyle V Aileen Mehle Selling at Doyle VII A New York City Private Estate Auction Schedule VIII Company Directory IX Absentee Bid Form XI INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Beverly Hills Collector A Connecticut Collector A Distinguished Lady A Lady A Pennsylvania Collector A Family of Spanish Descent Lot 519 5 3 1 2 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 Pair of Gold, Cabochon Peridot and High Karat Gold and Emerald Pair of High Karat Gold Earclips, Zolotas Gold ‘Mycenaean’ Necklace, Ilias Lalaounis Gold ‘Mycenaean’ Bracelet, Ilias Lalaounis Aquamarine and Mother-of-Pearl Earclips, Bangle Bracelet 22 kt., composed of hammered gold 18 kt., composed of pairs of scrolled links on 18 kt., composed of pairs of scrolled Elizabeth Locke 22 kt., the tubular bangle of polished twisted overlapping elongated oval bombé panels, a double strand mesh gold chain, links, no. F69, with maker’s mark, model 18 kt., the oval hammered gold stepped gold spaced by slender rope-twist bands, signed Zolotas, with maker’s mark, with maker’s mark, approximately 63 dwts. -

A Conversation with Metalsmith Cynthia Eid

artist profile A conversation with metalsmith Cynthia Eid Educator, author, and artist another piece, the better I like it. One of the most satisfying things Cynthia Eid is known for her about deep-drawing is turning the metal inside out. Metal is so stiff, but there are times when you can watch it flow like taffy. bold, adventurous forms that test the limits of metal’s structure. After getting your degree, you spent five years doing bench Twisted, but never tortured, her work. How necessary was that kind of training? On the one hand, I learned all sorts of things that I didn’t learn at pieces evoke the natural world the university. I learned to think faster, design faster, and work as seen through a dreamscape — faster. I learned a lot of technical stuff. But I also made a lot of ugly half-imagined versions of familiar stuff in the gold-jewelry factory where I worked for 3 years, and that was painful. So, I took pride in making the best hinges, organic forms. Eid is based in settings, molds, and box catches I could. Lexington, Massachusetts, teaches at workshops across the country, and has become known for her technical Any advice for jewelers just starting out? Make yourself rounded. There’s a lot to be said for knowing how expertise in new tools and materials, including Argentium Sterling Silver. [a] Sampler brooch. Sterling silver, 14k gold. 2¾ x 1¼ x ¼ in. (70 x 32 x 6.5mm). [b] Torsion pendant on handwoven chain. Sterling Your family was important in your becoming an artist, because silver, 14k and 18k gold, amethyst, pearls. -

Relationships with Jewellery?

How might a collaborative approach between maker and wearer yield sustainable `end-user' relationships with jewellery? Author Poppi, Clare Elizabeth Published 2018-12 Thesis Type Thesis (Masters) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/489 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/385867 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au How might a collaborative approach between maker and wearer yield sustainable ‘end-user’ relationships with jewellery? Clare Elizabeth Poppi (Bachelor of Fine Art) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Visual Arts Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Griffith University December 2018 Abstract In recent years, there has been a growing movement within contemporary jewellery that engages notions of sustainability. Part of this movement has involved focusing on the ethical concerns surrounding jewellery manufacture and production, from precious metal mining and gemstone sourcing through to studio techniques, including recycling, chemical reduction, and energy use. While these issues are imperative because of their social and environmental impacts, many jewellers focus solely on the role of the designer in ethical jewellery making. By contrast, my research examines the role of the wearer in accepting responsibility for their consumption habits. This exegesis explores how maker and wearer can collaborate in various ways to create ongoing, sustainable relationships between the wearer and their jewellery. i Statement of Originality: This work has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself. -

Note This List Is NOT 100% Correct

Note this list is NOT 100% Correct Ref Value product_name main_category 151 299 (1 Year Warranty) Suntaiho Quick Charging 3A USB Magnetic Charger Cable Mobiles & Accessories USB/Type C/iPhone Micro Cable 151 284 (COD) 9 Colors TWS Bluetooth Earphone inpods TWS i12 Earbuds Sports Airpod Mobiles & Accessories Headsets Wireless HiFi Colorful Headphone For iPhone and Android 151 448 (COD) 9 Colors TWS Bluetooth Earphone inpods TWS i12 Earbuds Sports Airpod Mobiles & Accessories Headsets Wireless HiFi Colorful Headphone For iPhone and Android 151 284 (COD) 9 Colors TWS Bluetooth Earphone inpods TWS i12 Earbuds Sports Airpod Mobiles & Accessories Headsets Wireless HiFi Colorful Headphone For iPhone and Android 151 364 **Antique Carved Wood Hand Crank Music Box Birthday Gifts Musical Box Toys, Games & Collectibles 151 338 [NNJXD]Baby Girl Dress Kids Dresses for Girls Christmas Party Santa Tulle Babies & Kids Princess Ball Gown 151 617 [NNJXD]Baby Girl Dress Lace Princess Girls Clothes Birthday Party Little Ball Kids Babies & Kids Clothes 151 200 [Seller Recommend] 3 Colors 1A 24V 8mm Mini IP 65 Waterproof Shock-proof Motors Car Momentary Push Button Power Switch Zi 151 534 [Spot] USB Flash Drive Metal With Customizable Logo Pen Drive Flash Stick For Laptops & Computers Portable Computer USB 2.0 32GB 16GB 8GB 4GB 2GB 1GB 151 341 【COD & Ready stock】Korean Skirt Women Elegant Plaid High Waist Skirts Women's Apparel denim skirt High waist skirt palda mini skirt 151 278 【COD】 Women Messenger Crossbody Bag Wallet Handbag Phone Pouch Women's Bags Case -

2017 Workshops Springs

Eureka 2017 Workshops Springs School of The Arts ESSA-ART.ORG 1 From our executive director Dear ESSA friends, When I first started working as ESSA’s Executive Director ten years ago, we had one building that served all needs…workshop space, ad- ministrative office, and dining area. All of our wood workshops were held at another location in town and when we started offering blacksmith- ing and metal fabrication workshops, we held them outside behind our main building that was nestled on less than an acre of land. Today, we have a 55 acre campus and our latest addition of a woodworking studio gives us the balance we’ve been dreaming about for years. We now Table of Contents have studio space for painting and drawing, clay building and throwing, jewelry making and the creation of small metal objects, blacksmithing and metal fabricating, weaving and working Workshop Info...........................................3 Master Schedule....................................4-5 with textiles, leather crafting, and now…wood turning and wood working. I hope you will help Youth Art Week...........................................5 us spread the word that the Eureka Springs School of the Arts is a full-blown campus offering a Workshops by Medium variety of workshops to meet a broad spectrum of creative needs! Painting & Drawing................................6-9 Small Metals......................................10-12 Sincerely, Clay...................................................12-13 Peggy Kjelgaard, Ph.D. Iron....................................................14-15 Executive Director Wood................................................16-18 Glass......................................................19 Textiles................................................20-21 Leather...............................................21-22 Special Media....................................22-23 Support for ESSA is provided, in part, by the Arkansas Arts Council, an agency of the Department of Arkansas Heritage and the National Endowment for the Arts.