Arapacana Alphabet Translation and Notes by Jayarava, April 2011 (Corrected 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mahayana Buddhism: the Doctrinal Foundations, Second Edition

9780203428474_4_001.qxd 16/6/08 11:55 AM Page 1 1 Introduction Buddhism: doctrinal diversity and (relative) moral unity There is a Tibetan saying that just as every valley has its own language so every teacher has his own doctrine. This is an exaggeration on both counts, but it does indicate the diversity to be found within Buddhism and the important role of a teacher in mediating a received tradition and adapting it to the needs, the personal transformation, of the pupil. This divers- ity prevents, or strongly hinders, generalization about Buddhism as a whole. Nevertheless it is a diversity which Mahayana Buddhists have rather gloried in, seen not as a scandal but as something to be proud of, indicating a richness and multifaceted ability to aid the spiritual quest of all sentient, and not just human, beings. It is important to emphasize this lack of unanimity at the outset. We are dealing with a religion with some 2,500 years of doctrinal development in an environment where scho- lastic precision and subtlety was at a premium. There are no Buddhist popes, no creeds, and, although there were councils in the early years, no attempts to impose uniformity of doctrine over the entire monastic, let alone lay, establishment. Buddhism spread widely across Central, South, South-East, and East Asia. It played an important role in aiding the cultural and spiritual development of nomads and tribesmen, but it also encountered peoples already very culturally and spiritually developed, most notably those of China, where it interacted with the indigenous civilization, modifying its doctrine and behaviour in the process. -

1 Essence of Paramartha Saara

ESSENCE OF PARAMARTHA SAARA (The Quintessence of Supreme Awareness) Edited and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities Essence of Manu Smriti*------------------- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. Kamakoti. Org/news as also on Google by the respective references. -

Our Path Together

OUR PATH TOGETHER HISTORICAL CONTEXT PHILOSOPHICAL/ CONSTRUCTIVE • What is whiteness? • How has Christianity produced & • What is Yogacara? supported whiteness? • Key ideas from the history of Yogacara • How has whiteness functioned in • Analysing and undoing whiteness with American Buddhism? Yogacara • How have Buddhists of Color confronted the dukkha of whiteness ? UNDOING WHITENESS WITH YOGACARA THOUGHT ZENJU EARTHLYN MANUEL: DHARMA AS EMBODIED DIFFERENCE THE EARLY YOGACARA SCHOOL • Dates: 2nd - 7th centuries CE • Writers: Asanga, Vasubandhu, Paramartha, Sthiramati, Dharmapala, Xuanzang, • Texts: • Sutras: Samdhinirmocana, Lankavatara and Daśabhūmika • Treatises: Mahayana-samgraha, Twenty Verses, Thirty Verses, Madhyanta-vibhaga, and Cheng weishi lun. • Major Concepts: the 8 consciousnesses; “mind only”; the three natures of dharmas MY METHOD HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY CONSTRUCTIVE PHILOSOPHY What does Yogacara say about ... How can these Yogacara points be applied to 3 key characteristics of whiteness: 1. The shape of consciousness 1. Ahistoricism 2. The relation between a subject and its object-world 2. Invisibility 3. The relationship between the experiences 3. Individualism and karma of individuals and groups HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY With a focus on the “mind” in “mind only” 1: MIND IS HISTORICAL Question: Do your 6 faculties present Key Terms: The 8 consciousnesses: to you the world “as it is”? 1-6) The 6 consciousnesses at the 6 Answer: Yogacara says NO. faculties 7) Afflicted consciousness Significance: Faculties don’t reveal historical & constructed nature of mind 8) Storehouse consciousness (alāya- or its objects. vijñāna) Plus: A note on the meaning of “historical” 2: MIND IS SUBJECTIVE & OBJECTIVE Question: Are subjects and objects produced Key Terms: separately or together? I) Constructed nature of a dharma Answer: Yogacara says TOGETHER. -

The Bodhisattva Ideal in Selected Buddhist

i THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL IN SELECTED BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES (ITS THEORETICAL & PRACTICAL EVOLUTION) YUAN Cl Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 ProQuest Number: 10672873 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672873 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis consists of seven chapters. It is designed to survey and analyse the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal and its gradual development in selected Buddhist scriptures. The main issues relate to the evolution of the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal. The Bodhisattva doctrine and practice are examined in six major stages. These stages correspond to the scholarly periodisation of Buddhist thought in India, namely (1) the Bodhisattva’s qualities and career in the early scriptures, (2) the debates concerning the Bodhisattva in the early schools, (3) the early Mahayana portrayal of the Bodhisattva and the acceptance of the six perfections, (4) the Bodhisattva doctrine in the earlier prajhaparamita-siltras\ (5) the Bodhisattva practices in the later prajnaparamita texts, and (6) the evolution of the six perfections (paramita) in a wide range of Mahayana texts. -

Early Forebodings of the Death of Buddhism* David

EARLY FOREBODINGS OF THE DEATH OF BUDDHISM* DAVID WELLINGTON CHAPPELL TABLEOF CONTENTS Five Reasons for the Disappearance of Buddhism. - External Threats to Bud- dhism. - Pali Timetables of Decline. - Timetables of Decline in Chinese Translations. - Approaching the End of Buddhism. - Dating According to Stages of Decline. - The Nirvana Sutra. - Period of the Five Corruptions. - Hui-ssu (515-577) and the Arrival of the Last Period. - Narendrayasas and the Three-Periods Concept. - The Response of Chinese Buddhists. - Conclusion. It is well known that the great Japanese reformation of Buddhism during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) took place in a climate of crisis. A visible symbol of this was the widespread feeling that Bud- dhism had entered its final period (mappo). Honen (1133-1212), Shinran (1173-1262), and Nichiren (1222-1282) all used the idea of mappõ1 to justify and explain the radical departures that they felt were necessary and which in each case resulted in an important new school of Buddhism. They echoed one another in proclaiming that traditional Buddhism was on its last legs and that people of this final period no longer had the capacity to understand or practice Bud- dhism. But instead of leading to despair, the acceptance of the idea of the death of Buddhism actually stimulated these Buddhist leaders to establish new forms for this period of emergency. Fortunately, within the Buddhist tradition itself was the predic- tion that these "last days" would occur. Thus, the innovators of Kamakura were able to affirm the Buddhist tradition while simultaneously changing it. The prediction by Buddhists that Bud- dhism would die out is not just a curious and creative aberration which arose in Japan. -

The Diamond Sutra

THE DIAMOND SUTRA THE DIAMOND SUTRA 1 Diamond Sutra The full Sanskrit title of this text is the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (The Vajra Prajna Paramita Sutra). The Buddha said this Sutra may be known as “The Diamond that Cuts through Illusion.” Like many Buddhist sūtras, The Diamond Sūtra begins with the famous phrase, "Thus have I heard." The Buddha finished his daily walk with the monks to gather offerings of food and sits down to rest. The monk Subhūti comes forth and asks the Buddha a question. What follows is a dialogue regarding the nature of perception. The Buddha often uses paradoxical phrases such as, "What is called the highest teaching is not the highest teaching". The Buddha is generally thought to be helping Subhūti unlearn his preconceived, limited notions of the nature of reality and enlightenment. The Diamond Sūtra is a short and well-known Mahāyāna sūtra from the Prajñāpāramitā, or "Perfection of Wisdom" genre, and it emphasizes the practice of non-abiding and non-attachment. A list of vivid metaphors for impermanence appears in a popular four-line verse at the end of the sūtra: All conditioned phenomena Are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, or shadows; Like drops of dew, or flashes of lightning; Thusly should they be contemplated. A copy of the Chinese version of The Diamond Sūtra, found among the Dunhuang manuscripts in the early 20th century and dating back to May 11, THE DIAMOND SUTRA 868 C.E. is considered the earliest complete survival of a woodblock printing folio. This discovered text was made over 500 years before the Gutenberg 2 printing press in 1450 C.E. -

The Concept of Upaya (方便) in Mahayana Buddhist Philosophy

The Concept of Upaya (方便) in Mahayana Buddhist Philosophy Daigan a n d Alicia M a t s u n a g a Upaya is a widely used term in Buddhism, commonly rendered into English by translations such as “ expediency,” “skillful means” and “ adapted teachings.” None of these terms is adequate or conveys the immense significance of the concept. For example, both “expediency” and “adapted teaching55 bear pejorative utilitarian connotations, while “skillful means” is aoristic without further elucidation. Such renditions imply that upaya are inferior teachings bearing only a marginal relationship to Buddhist philosophy. In fact a number of individuals mistakenly believe this to be the case and relegate the entire concept to the realm of secondary doctrine. The purpose of this essay is to systematically analyze the role of upaya in Mahayana Buddhist philosophy and its relationship to Nirvana. The Buddha and Upaya The vast system of Buddhist theology1 and philosophy originated from the spiritual realization of a single man, Gotama Buddha. He was historically the first to encounter the formidable task of communicating enlightenment, whicn is an intuitive experience transcending conventional language and thought, to the non enlightened. It was obvious that such communication would 1 . The term “ theology” is here used in reference to Buddhism with the Til- lichean connotation “a matter of ultimate concern.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1 / 1 March 1974 51 The Concept of Upaya ( 方便)in Mahayana Buddhist Philosophy only be perfect if the listener himself could share the experience. But enlightenment is based on a comprehension of “interde pendent origination” (Pali, Paticca samuppada), which entails a radical reorientation from the accepted mode of daily life of the common man. -

Mahayana Buddhism: the Doctrinal Foundations

9780203428474_1_pre.qxd 16/6/08 11:54 AM Page v To all my dear colleagues past and present at the University of Bristol’s Department of Theology and Religious Studies 9780203428474_1_pre.qxd 18/6/08 3:04 PM Page i MahÖyÖna Buddhism ‘The publication of Paul Williams’ MahAyAna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations in 1989 was a milestone in the development of Buddhist Studies, being the first truly comprehen- sive and authoritative attempt to chart the doctrinal landscape of Mahayana Buddhism in its entirety. Previous scholars like Edward Conze and Etienne Lamotte had set themselves this daunting task, but it had proved beyond them. Williams not only succeeded in finish- ing the job, but did it so well that his book has remained the primary work on the subject, and the textbook of choice for teachers of university courses on Buddhism, for 20 years. It is still unrivalled. This makes a second edition all the more welcome. Williams has extens- ively revised and updated the book in the light of the considerable scholarship published in this area since 1989, at the same time enlarging many of his thoughtful discussions of Mahayana Buddhist philosophical issues. The result is a tour de force of breadth and depth combined. I confidently expect that Williams’ richly detailed map of this field will remain for decades to come an indispensable guide to all those who venture into it.’ Paul Harrison, George Edwin Burnell Professor of Religious Studies, Stanford University Originating in India, Mahayana Buddhism spread across Asia, becoming the prevalent form of Buddhism in Tibet and East Asia. -

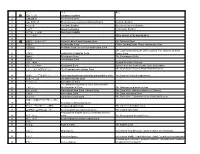

中文梵文英文1 佛釋迦牟尼佛sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛

中文 梵文 英文 1 佛 釋迦牟尼佛 Sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛 Vairocana Buddha 3 藥師璢璃光佛 Bhaiṣajya-guru-vaiḍūrya-prabhāṣa Buddha Medicine Buddha 4 阿彌陀佛 Amitābha Buddha Boundless radiance Buddha 5 不動佛 Akṣobhya Buddha Unshakable Buddha 6 然燈佛, 定光佛 Dipamkara Buddha 7 東方青龍佛 Azure Dragon of the East Buddha 8 9 經 金剛般若波羅密多經 Vajracchedika Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra The Diamond Sutra 10 華嚴經 Avataṃsaka Sutra Flower Garland Sutra; Flower Adornment Sutra 11 阿彌陀經 Amitābha Sutra; Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra The Lotus Sutra; Discourse of the Lotus of True Dharma; Dharma 12 法華經 Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sutra Flower Sutra; 13 楞嚴經 Śūraṅgama Sutra The Shurangama Sutra 14 楞伽經 Lankāvatāra Sūtra 15 四十二章經 Sutra in Forty-two Sections 16 地藏菩薩本願經 Kṣitigarbha Sutra Sutra of the Past Vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva 17 心經 ; 般若波羅蜜多心經 The Prajnaparamita Hrdaya Sutra The Heart Sutra, Heart of Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra 18 圓覺經;大方广圆觉修多罗了义经 Mahāvaipulya pūrṇabuddhasūtra prassanārtha sūtra The Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment 19 維摩詰所說經 Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa sūtra 20 三摩地王经 Samadhi-raja Sutra The Mahā prajñā pāramitā-sūtra; Śatasāhasrikā 21 大般若經 Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra; The Maha prajna paramita sutras 22 大般涅槃經 Mahā parinirvāṇa Sutra, Nirvana Sutra The Sutra of the ultimate extinction of Dharma 23 梵網經 Brahmajāla Sutra The Sutra of Brahma's Net 24 解深密經 Sandhinirmocana Sutra The Sutra of the Explanation of the Profound Secrets 勝鬘経;勝鬘師子吼一乘大方便方 25 廣經 Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra 26 佛说观无量寿佛经;十六觀經 Amitayur-dhyana Sutra The sixteen contemplate sutra 27 金光明經;金光明最勝王經 Suvarṇa-prabhāsa-uttamarāja Sutra The Golden-light Sutra -

On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India, 629-645 A.D

-tl Strata, Sfew Qotlt BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE WASON ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF CHARLES W. WASON CORNELL 76 1918 ^He due fnterllbrary Io^jj KlYSILL The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071132769 ORIENTAL TRANSLATION FUND NEW SEFtlES. VOL. XIV. 0^ YUAN CHWAIG'S TRAVELS IN INDIA 629—645 A, D. THOMAS WATTERS M.R.A.S. EDITED, APTER HIS DEATH, T. W. RHYS DAVIDS, F.B.A. S. W. BUSHELL, M.D.; C.M.G. ->is<- LONDON ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY 22 ALBXMASLE STBBET 1904 w,\^q4(^ Ketrinttd by the Radar Promt hy C. G. RSder Ltd., LeipBig, /g2J. CONTENTS. PEEFACE V THOMAS WAITERS Vm TBANSIilTEEATION OF THE PlLGEEVl's NAME XI CHAP. 1. TITLE AND TEXT 1 2. THE INTBODUCTION 22 3. FEOM KAO CHANG TO THE THOUSAMD 8PEINGS . 44 4. TA&AS TO KAPIS ..." 82 5. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OP INDIA 131 6. LAMPA TO GANDHARA 180 7. UDTANA TO TrASTTMTR. 225 8. K4.SHMIB TO RAJAPUE 258 9. CHEH-KA TO MATHUEA 286 10. STHANESVAEA TO KAMTHA 316 11. KANTAKUBJA TO VI^OKA 340 12. SEAVASTI TO KUSINAEA 377 PREFACE. As will be seen from Dr. Bushell's obituary notice of Thomas "Watters, republished from the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society for 1901 at the end of those few words of preface, Mr, Watters left behind him a work, ready for the press, on the travels of Ylian-Chwang in India in the 7*'' Century a. -

The Vijnaptimatrata Buddhism of the Chinese Monk K'uei

THE VIJNAPTIMATRATA BUDDHISM OF THE CHINESE MONK K'UEI-CHI (A.D. 632-682) ALAN SPONBERG B.A. , American University, 1968 M.A. , University of Wisconsin, 1972 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ; THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Asian Studies We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard. THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1979 © Alan Sponberg, 1979 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 DE-6 BP 75-51 1 E ABSTRACT The dissertation seeks to determine the main features of the Buddhist thought of K'uei-chi, First Patriarch of the Fa-hsiang School of East Asian Buddhism, and to further establish his position as a key figure in the transmission of Indian philosophical traditions into China.. In addition it provides a translation of an original essay written "by K'uei-chi on Vijnaptimatrata. (Mere Conceptualization) the fundamental philosophic principle of the School of Yogacara Buddhism to which he was heir. There are two parts to the dissertation: Part One comprising Chapts. -

Evidence That Paramārtha Composed the Awakening of Faith

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Roger Jackson Depl. of Religion Carleton College Northfield, MN 55057 EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Vrbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universitede Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo,Japan Steven Collins Robert Thurman Concordia University Amherst College Montreal, Canada Amherst, Massachusetts, USA Volume 12 1989 Number 1 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. Hodgson's Blind Alley? On the So-called Schools of Nepalese Buddhism by David N. Gellner 7 2. Truth, Contradiction and Harmony in Medieval Japan: Emperor Hanazono (1297-1348) and Buddhism by Andrew Goble 21 3. The Categories of T'i, Hsiang, and Yung: Evidence that Paramartha Composed the Awakening of Faith by William H. Grosnick 65 4. Asariga's Understanding of Madhyamika: Notes on the Shung-chung-lun by John P. Keenan 93 5. Mahayana Vratas in Newar Buddhism by Todd L. Lewis 109 6. The Kathavatthu Niyama Debates by James P McDermott 139 II. SHORT PAPERS 1. A Verse from the Bhadracaripranidhdna in a 10th Century Inscription found at Nalanda by Gregory Schopen 149 2. A Note on the Opening Formula of Buddhist Sutras by Jonathan A. Silk 158 III. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Die Frau imfriihen Buddhismus, by Renata Pitzer-Reyl (Vijitha Rajapakse) 165 Alayavijndna: On the Origin and the Early Development of a Central Concept of Yogacara Philosophy by Iambert Schmithausen (Paul J. Griffiths) 170 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS 178 The Categories of T'i, Hsiang, and Yimg: Evidence that Paramartha Composed the Awakening of Faith by William H.