Well-Appearing Newborn with a Vesiculobullous Rash at Birth Sarah E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of medicines belonging to the ATC group R01 (Nasal preparations) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 5 DISCLAIMER 7 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 8 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Cyclopentamine (ATC: R01AA02) 10 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AA03) 11 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AA04) 14 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AA05) 16 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AA06) 19 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AA07) 20 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AA08) 23 Tramazoline (ATC: R01AA09) 26 Metizoline (ATC: R01AA10) 29 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AA11) 30 Fenoxazoline (ATC: R01AA12) 31 Tymazoline (ATC: R01AA13) 32 Epinephrine (ATC: R01AA14) 33 Indanazoline (ATC: R01AA15) 34 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AB01) 35 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AB02) 37 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AB03) 39 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AB05) 40 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AB06) 41 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AB07) 45 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AB08) 46 Cromoglicic Acid (ATC: R01AC01) 49 2 Levocabastine (ATC: R01AC02) 51 Azelastine (ATC: R01AC03) 53 Antazoline (ATC: R01AC04) 56 Spaglumic Acid (ATC: R01AC05) 57 Thonzylamine (ATC: R01AC06) 58 Nedocromil (ATC: R01AC07) 59 Olopatadine (ATC: R01AC08) 60 Cromoglicic Acid, Combinations (ATC: R01AC51) 61 Beclometasone (ATC: R01AD01) 62 Prednisolone (ATC: R01AD02) 66 Dexamethasone (ATC: R01AD03) 67 Flunisolide (ATC: R01AD04) 68 Budesonide (ATC: R01AD05) 69 Betamethasone (ATC: R01AD06) 72 Tixocortol (ATC: R01AD07) 73 Fluticasone (ATC: R01AD08) 74 Mometasone (ATC: R01AD09) 78 Triamcinolone (ATC: R01AD11) 82 -

4. Antibacterial/Steroid Combination Therapy in Infected Eczema

Acta Derm Venereol 2008; Suppl 216: 28–34 4. Antibacterial/steroid combination therapy in infected eczema Anthony C. CHU Infection with Staphylococcus aureus is common in all present, the use of anti-staphylococcal agents with top- forms of eczema. Production of superantigens by S. aureus ical corticosteroids has been shown to produce greater increases skin inflammation in eczema; antibacterial clinical improvement than topical corticosteroids alone treatment is thus pivotal. Poor patient compliance is a (6, 7). These findings are in keeping with the demon- major cause of treatment failure; combination prepara- stration that S. aureus can be isolated from more than tions that contain an antibacterial and a topical steroid 90% of atopic eczema skin lesions (8); in one study, it and that work quickly can improve compliance and thus was isolated from 100% of lesional skin and 79% of treatment outcome. Fusidic acid has advantages over normal skin in patients with atopic eczema (9). other available topical antibacterial agents – neomycin, We observed similar rates of infection in a prospective gentamicin, clioquinol, chlortetracycline, and the anti- audit at the Hammersmith Hospital, in which all new fungal agent miconazole. The clinical efficacy, antibac- patients referred with atopic eczema were evaluated. In terial activity and cosmetic acceptability of fusidic acid/ a 2-month period, 30 patients were referred (22 children corticosteroid combinations are similar to or better than and 8 adults). The reason given by the primary health those of comparator combinations. Fusidic acid/steroid physician for referral in 29 was failure to respond to combinations work quickly with observable improvement prescribed treatment, and one patient was referred be- within the first week. -

Updates in Pediatric Dermatology

Peds Derm Updates ELIZABETH ( LISA) SWANSON , M D ADVANCED DERMATOLOGY COLORADO ROCKY MOUNTAIN HOSPITAL FOR CHILDREN [email protected] Disclosures Speaker Sanofi Regeneron Amgen Almirall Pfizer Advisory Board Janssen Powerpoints are the peacocks of the business world; all show, no meat. — Dwight Schrute, The Office What’s New In Atopic Dermatitis? Impact of Atopic Dermatitis Eczema causes stress, sleeplessness, discomfort and worry for the entire family Treating one patient with eczema is an example of “trickle down” healthcare Patients with eczema have increased risk of: ADHD Anxiety and Depression Suicidal Ideation Parental depression Osteoporosis and osteopenia (due to steroids, decreased exercise, and chronic inflammation) Impact of Atopic Dermatitis Sleep disturbances are a really big deal Parents of kids with atopic dermatitis lose an average of 1-1.5 hours of sleep a night Even when they sleep, kids with atopic dermatitis don’t get good sleep Don’t enter REM as much or as long Growth hormone is secreted in REM (JAAD Feb 2018) Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergies Growing evidence that food allergies might actually be caused by atopic dermatitis Impaired barrier allows food proteins to abnormally enter the body and stimulate allergy Avoiding foods can be harmful Proper nutrition is important Avoidance now linked to increased risk for allergy and anaphylaxis Refer severe eczema patients to Allergist before 4-6 mos of age to talk about food introduction Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis Skin barrier -

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using Machine Learning

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy using Machine Learning Kate Wang et al. Supplemental Table S1. Drugs selected by Pharmacophore-based, ML-based and DL- based search in the FDA-approved drugs database Pharmacophore WEKA TF 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3- 5-O-phosphono-alpha-D- (phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)) ribofuranosyl diphosphate Acarbose Amikacin Acetylcarnitine Acetarsol Arbutamine Acetylcholine Adenosine Aldehydo-N-Acetyl-D- Benserazide Acyclovir Glucosamine Bisoprolol Adefovir dipivoxil Alendronic acid Brivudine Alfentanil Alginic acid Cefamandole Alitretinoin alpha-Arbutin Cefdinir Azithromycin Amikacin Cefixime Balsalazide Amiloride Cefonicid Bethanechol Arbutin Ceforanide Bicalutamide Ascorbic acid calcium salt Cefotetan Calcium glubionate Auranofin Ceftibuten Cangrelor Azacitidine Ceftolozane Capecitabine Benserazide Cerivastatin Carbamoylcholine Besifloxacin Chlortetracycline Carisoprodol beta-L-fructofuranose Cilastatin Chlorobutanol Bictegravir Citicoline Cidofovir Bismuth subgallate Cladribine Clodronic acid Bleomycin Clarithromycin Colistimethate Bortezomib Clindamycin Cyclandelate Bromotheophylline Clofarabine Dexpanthenol Calcium threonate Cromoglicic acid Edoxudine Capecitabine Demeclocycline Elbasvir Capreomycin Diaminopropanol tetraacetic acid Erdosteine Carbidopa Diazolidinylurea Ethchlorvynol Carbocisteine Dibekacin Ethinamate Carboplatin Dinoprostone Famotidine Cefotetan Dipyridamole Fidaxomicin Chlormerodrin Doripenem Flavin adenine dinucleotide -

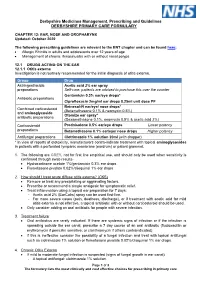

EAR, NOSE and OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020

Derbyshire Medicines Management, Prescribing and Guidelines DERBYSHIRE PRIMARY CARE FORMULARY CHAPTER 12: EAR, NOSE AND OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020 The following prescribing guidelines are relevant to the ENT chapter and can be found here: • Allergic Rhinitis in adults and adolescents over 12 years of age • Management of chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps 12.1 DRUGS ACTING ON THE EAR 12.1.1 Otitis externa Investigation is not routinely recommended for the initial diagnosis of otitis externa. Group Drug Astringent/acidic Acetic acid 2% ear spray preparations Self-care: patients are advised to purchase this over the counter Gentamicin 0.3% ear/eye drops* Antibiotic preparations Ciprofloxacin 2mg/ml ear drops 0.25ml unit dose PF Betnesol-N ear/eye/ nose drops* Combined corticosteroid (Betamethasone 0.1% & neomycin 0.5%) and aminoglycoside Otomize ear spray* antibiotic preparations (Dexamethasone 0.1%, neomycin 0.5% & acetic acid 2%) Corticosteroid Prednisolone 0.5% ear/eye drops Lower potency preparations Betamethasone 0.1% ear/eye/ nose drops Higher potency Antifungal preparations Clotrimazole 1% solution 20ml (with dropper) * In view of reports of ototoxicity, manufacturers contra-indicate treatment with topical aminoglycosides in patients with a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum) or patent grommet. 1. The following are GREY, not for first line empirical use, and should only be used when sensitivity is confirmed through swab results- • Hydrocortisone acetate 1%/gentamicin 0.3% ear drops • Flumetasone pivalate 0.02%/clioquinol 1% ear drops 2. How should I treat acute diffuse otitis externa? (CKS) • Remove or treat any precipitating or aggravating factors. • Prescribe or recommend a simple analgesic for symptomatic relief. -

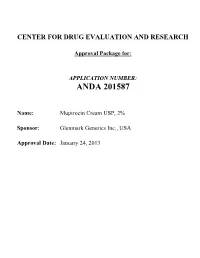

Mupirocin Cream USP, 2%

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH Approval Package for: APPLICATION NUMBER: ANDA 201587 Name: Mupirocin Cream USP, 2% Sponsor: Glenmark Generics Inc., USA Approval Date: January 24, 2013 CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: ANDA 201587 CONTENTS Reviews / Information Included in this Review Approval Letter X Other Action Letters Labeling X Labeling Review(s) X Medical Review(s) Chemistry Review(s) X Pharm/Tox Review(s) Statistical Review(s) X Microbiology Review(s) Bioequivalence Review(s) X Other Review(s) X Administrative & Correspondence Documents X CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: ANDA 201587 APPROVAL LETTER DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Rockville, MD 20857 ANDA 201587 Glenmark Generics Inc., USA U.S. Agent for: Glenmark Generics Ltd. Attention: William R. McIntyre, Ph.D. Executive Vice President, Regulatory Affairs 750 Corporate Drive Mahwah, NJ 07430 Dear Sir: This is in reference to your abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) dated February 22, 2010, submitted pursuant to section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the Act), for Mupirocin Cream USP, 2%. Reference is also made to your amendments dated June 1, 2010; August 16, 2011; and January 19, January 27, April 27, July 18, and July 20, 2012. We also acknowledge receipt of your correspondence dated November 2, 2012, addressing patent issues associated with this ANDA. We have completed the review of this ANDA and have concluded that adequate information has been presented to demonstrate that the drug is safe and effective for use as recommended in the submitted labeling. Accordingly the ANDA is approved, effective on the date of this letter. -

Download/View

IAJPS 2017, 4 (10), 3647-3656 RVVS Prasanna Kumari et al ISSN 2349-7750 CODEN [USA]: IAJPBB ISSN: 2349-7750 INDO AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1012459 Available online at: http://www.iajps.com Research Article STABILITY INDICATING RP-HPLC METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION FOR THE SIMULTANEOUS ESTIMATION OF MUPIROCIN AND FLUTICASONE RVVS Prasanna Kumari1*, K. Mangamma2, Dr. S. V. U. M. Prasad3 1 B.Pharm. School of Pharmaceutical Sciences &Technologies, JNTUK, Kakinada. 2M. Pharm, (Ph.D), School of Pharmaceutical Sciences & Technologies, Institute of Science & Technology, JNTUK, Kakinada. 3M.Pharm, Ph.D., School of Pharmaceutical Sciences & Technologies, JNTUK, Kakinada. Abstract: A simple, Accurate, precise method was developed for the simultaneous estimation of the Mupirocin and Fluticasone in ointment dosage form by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography. Chromatogram was run through Standard Discovery 250 x 4.6 mm, 5. Mobile phase containing Buffer Ortho phosphoric acid: Acetonitrile taken in the ratio 55:45 was pumped through column at a flow rate of 1ml/min. Buffer used in this method was 0.1% Perchloric acid buffer. Temperature was maintained at 30°C. Optimized wavelength selected was 230nm. Retention time of Mupirocin and Fluticasone were found to be 2.146 min and 2.770 min. percentage relative standard deviation of the Mupirocin and Fluticasone were and found to be 0.4 and 0.5 respectively. Percentage Recovery was obtained as 98.75% and 99.42% for Mupirocin and Fluticasone respectively. Limit of detection, Limit of quantitation values obtained from regression equations of Mupirocin and Fluticasone were 0.38, 1.16 and 0.02, 0.05 respectively. -

Efficacy of Anti-Biofilm Gel, Chitogel-Mupirocin-Budesonide in a Sheep Sinusitis Model

8 Original Article Page 1 of 9 Efficacy of anti-biofilm gel, chitogel-mupirocin-budesonide in a sheep sinusitis model Mian Li Ooi1, Amanda J. Drilling1, Craig James2, Stephen Moratti3, Sarah Vreugde1, Alkis J. Psaltis1, Peter-John Wormald1 1Department of Surgery-Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Basil Hetzel Institute for Translational Health Research, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia; 2Clinpath Laboratories, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia; 3Department of Chemistry, Otago University, Dunedin, New Zealand Contributions: (I) Conception and design: ML Ooi, AJ Drilling, S Vreugde, AJ Psaltis, PJ Wormald; (II) Administrative support: ML Ooi; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: S Moratti; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: ML Ooi; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: ML Ooi, C James; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Peter-John Wormald. Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, 3C, Level 3, 28 Woodville Road, Woodville West, 5011 South Australia, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Background: The search for effective topical anti-inflammatory and antibiofilm delivery to manage recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) continues to be elusive. The ideal topical treatment aims to provide adequate contact time for treatment agents to exert its effect on sinus mucosa. Our study presents the in vivo efficacy of chitogel (CG), combined with anti-inflammatory agent budesonide and antibiofilm agent mupirocin (CG-BM) for treatment of S. aureus biofilms. Methods: In established sheep sinusitis model, 15 sheep were randomised into three groups (5 sheep, n=10 sinuses, per treatment): (I) twice daily saline flush (NT), (II) CG with twice daily saline flush, and (III) CG- BM with twice daily saline flush for 7-days. -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

GAO-09-245 Nonprescription Drugs

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters GAO February 2009 NONPRESCRIPTION DRUGS Considerations Regarding a Behind-the-Counter Drug Class GAO-09-245 February 2009 NONPRESCRIPTION DRUGS Accountability Integrity Reliability Considerations Regarding a Behind-the-Counter Drug Highlights Class Highlights of GAO-09-245, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found In the United States, most Arguments supporting and opposing a BTC drug class in the United States nonprescription drugs are available have been based on public health and health care cost considerations, and over-the-counter (OTC) in reflect general disagreement on the likely consequences of establishing such a pharmacies and other stores. class. Proponents of a BTC drug class suggest it would lead to improved Experts have suggested that drug public health through increased availability of nonprescription drugs and availability could be increased by establishing an additional class of greater use of pharmacists’ expertise. Opponents are concerned that a BTC nonprescription drugs that would drug class might become the default for drugs switching from prescription to be held behind the counter (BTC) nonprescription status, thus reducing consumers’ access to drugs that would but would require the intervention otherwise have become available OTC, and argue that pharmacists might not of a pharmacist before being be able to provide high quality BTC services. Proponents of a BTC drug class dispensed; a similar class of drugs point to potentially reduced costs through a decrease in the number of exists in many other countries. physician visits and a decline in drug prices that might result from switches of Although the Food and Drug drugs from prescription to nonprescription status. -

Dr. Jack Newman's All Purpose Nipple Ointment

Dr. Jack Newman’s All Purpose Nipple Ointment (APNO) We call our nipple ointment “all purpose” since it contains ingredients that help deal with multiple causes or aggravating factors of sore nipples. “Good medicine” calls for the single “right” treatment for the “right” problem, true enough, but mothers with sore nipples don’t have time to try out different treatments that may or may not work, so we have combined various treatments in one ointment. Of course, preventing sore nipples in the first place would be the best treatment and often adjusting how the baby takes the breast can do more than anything to decrease and eliminate the mother’s nipple soreness (See information sheets When Latching, Sore Nipples as well as the video clips at the website nbci.ca. The APNO contains: 1. Mupirocin 2% ointment. Mupirocin (Bactroban is the trade name) is an antibiotic that is effective against many bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus aureus including MRSA (methicillin resistantStaphylococcus aureus). Staphylococcus aureus is commonly found growing in abrasions or cracks in the nipples and probably makes worse whatever the initial cause of sore nipples is. Interestingly, mupirocin apparently has some effect against Candida albicans (commonly, but inaccurately called “thrush” or “yeast”). Treatment of sore nipples with an antibiotic alone sometimes seems to work, but we feel that the antibiotic works best in combination with the other ingredients discussed below. Although mupirocin is absorbed when taken by mouth, it is so quickly metabolized in the body that it is destroyed before blood levels can be measured. Moreover most of it gets stuck to the skin so that very little is taken in by the baby. -

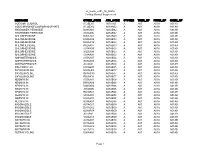

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01