WHO Drug Information Vol. 03, No. 4, 1989

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Similarities and Differences 2 www.ccfa.org IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 Important Differences Between IBD and IBS Many diseases and conditions can affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is part of the digestive system and includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. These diseases and conditions include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 www.ccfa.org 3 Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflammatory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflamma- Causes tory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. The two most com- The exact cause of IBD remains unknown. Researchers mon inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease believe that a combination of four factors lead to IBD: a (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD affects as many as 1.4 genetic component, an environmental trigger, an imbal- million Americans, most of whom are diagnosed before ance of intestinal bacteria and an inappropriate reaction age 35. There is no cure for IBD but there are treatments to from the immune system. Immune cells normally protect reduce and control the symptoms of the disease. the body from infection, but in people with IBD, the immune system mistakes harmless substances in the CD and UC cause chronic inflammation of the GI tract. CD intestine for foreign substances and launches an attack, can affect any part of the GI tract, but frequently affects the resulting in inflammation. -

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of medicines belonging to the ATC group R01 (Nasal preparations) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 5 DISCLAIMER 7 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 8 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Cyclopentamine (ATC: R01AA02) 10 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AA03) 11 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AA04) 14 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AA05) 16 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AA06) 19 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AA07) 20 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AA08) 23 Tramazoline (ATC: R01AA09) 26 Metizoline (ATC: R01AA10) 29 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AA11) 30 Fenoxazoline (ATC: R01AA12) 31 Tymazoline (ATC: R01AA13) 32 Epinephrine (ATC: R01AA14) 33 Indanazoline (ATC: R01AA15) 34 Phenylephrine (ATC: R01AB01) 35 Naphazoline (ATC: R01AB02) 37 Tetryzoline (ATC: R01AB03) 39 Ephedrine (ATC: R01AB05) 40 Xylometazoline (ATC: R01AB06) 41 Oxymetazoline (ATC: R01AB07) 45 Tuaminoheptane (ATC: R01AB08) 46 Cromoglicic Acid (ATC: R01AC01) 49 2 Levocabastine (ATC: R01AC02) 51 Azelastine (ATC: R01AC03) 53 Antazoline (ATC: R01AC04) 56 Spaglumic Acid (ATC: R01AC05) 57 Thonzylamine (ATC: R01AC06) 58 Nedocromil (ATC: R01AC07) 59 Olopatadine (ATC: R01AC08) 60 Cromoglicic Acid, Combinations (ATC: R01AC51) 61 Beclometasone (ATC: R01AD01) 62 Prednisolone (ATC: R01AD02) 66 Dexamethasone (ATC: R01AD03) 67 Flunisolide (ATC: R01AD04) 68 Budesonide (ATC: R01AD05) 69 Betamethasone (ATC: R01AD06) 72 Tixocortol (ATC: R01AD07) 73 Fluticasone (ATC: R01AD08) 74 Mometasone (ATC: R01AD09) 78 Triamcinolone (ATC: R01AD11) 82 -

4. Antibacterial/Steroid Combination Therapy in Infected Eczema

Acta Derm Venereol 2008; Suppl 216: 28–34 4. Antibacterial/steroid combination therapy in infected eczema Anthony C. CHU Infection with Staphylococcus aureus is common in all present, the use of anti-staphylococcal agents with top- forms of eczema. Production of superantigens by S. aureus ical corticosteroids has been shown to produce greater increases skin inflammation in eczema; antibacterial clinical improvement than topical corticosteroids alone treatment is thus pivotal. Poor patient compliance is a (6, 7). These findings are in keeping with the demon- major cause of treatment failure; combination prepara- stration that S. aureus can be isolated from more than tions that contain an antibacterial and a topical steroid 90% of atopic eczema skin lesions (8); in one study, it and that work quickly can improve compliance and thus was isolated from 100% of lesional skin and 79% of treatment outcome. Fusidic acid has advantages over normal skin in patients with atopic eczema (9). other available topical antibacterial agents – neomycin, We observed similar rates of infection in a prospective gentamicin, clioquinol, chlortetracycline, and the anti- audit at the Hammersmith Hospital, in which all new fungal agent miconazole. The clinical efficacy, antibac- patients referred with atopic eczema were evaluated. In terial activity and cosmetic acceptability of fusidic acid/ a 2-month period, 30 patients were referred (22 children corticosteroid combinations are similar to or better than and 8 adults). The reason given by the primary health those of comparator combinations. Fusidic acid/steroid physician for referral in 29 was failure to respond to combinations work quickly with observable improvement prescribed treatment, and one patient was referred be- within the first week. -

Updates in Pediatric Dermatology

Peds Derm Updates ELIZABETH ( LISA) SWANSON , M D ADVANCED DERMATOLOGY COLORADO ROCKY MOUNTAIN HOSPITAL FOR CHILDREN [email protected] Disclosures Speaker Sanofi Regeneron Amgen Almirall Pfizer Advisory Board Janssen Powerpoints are the peacocks of the business world; all show, no meat. — Dwight Schrute, The Office What’s New In Atopic Dermatitis? Impact of Atopic Dermatitis Eczema causes stress, sleeplessness, discomfort and worry for the entire family Treating one patient with eczema is an example of “trickle down” healthcare Patients with eczema have increased risk of: ADHD Anxiety and Depression Suicidal Ideation Parental depression Osteoporosis and osteopenia (due to steroids, decreased exercise, and chronic inflammation) Impact of Atopic Dermatitis Sleep disturbances are a really big deal Parents of kids with atopic dermatitis lose an average of 1-1.5 hours of sleep a night Even when they sleep, kids with atopic dermatitis don’t get good sleep Don’t enter REM as much or as long Growth hormone is secreted in REM (JAAD Feb 2018) Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergies Growing evidence that food allergies might actually be caused by atopic dermatitis Impaired barrier allows food proteins to abnormally enter the body and stimulate allergy Avoiding foods can be harmful Proper nutrition is important Avoidance now linked to increased risk for allergy and anaphylaxis Refer severe eczema patients to Allergist before 4-6 mos of age to talk about food introduction Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis Skin barrier -

Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play

The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Executive Agency for Health and Consumers Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play 24 January 2012 Final Report Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Acknowledgements Matrix Insight Ltd would like to thank everyone who has contributed to this research. We are especially grateful to the following institutions for their support throughout the study: the Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU) including their national member associations in Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Poland and the United Kingdom; the European Medical Association (EMANET); the Observatoire Social Européen (OSE); and The Netherlands Institute for Health Service Research (NIVEL). For questions about the report, please contact Dr Gabriele Birnberg ([email protected] ). Matrix Insight | 24 January 2012 2 Health Reports for Mutual Recognition of Medical Prescriptions: State of Play Executive Summary This study has been carried out in the context of Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients’ rights in cross- border healthcare (CBHC). The CBHC Directive stipulates that the European Commission shall adopt measures to facilitate the recognition of prescriptions issued in another Member State (Article 11). At the time of submission of this report, the European Commission was preparing an impact assessment with regards to these measures, designed to help implement Article 11. -

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using Machine Learning

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy using Machine Learning Kate Wang et al. Supplemental Table S1. Drugs selected by Pharmacophore-based, ML-based and DL- based search in the FDA-approved drugs database Pharmacophore WEKA TF 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3- 5-O-phosphono-alpha-D- (phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)) ribofuranosyl diphosphate Acarbose Amikacin Acetylcarnitine Acetarsol Arbutamine Acetylcholine Adenosine Aldehydo-N-Acetyl-D- Benserazide Acyclovir Glucosamine Bisoprolol Adefovir dipivoxil Alendronic acid Brivudine Alfentanil Alginic acid Cefamandole Alitretinoin alpha-Arbutin Cefdinir Azithromycin Amikacin Cefixime Balsalazide Amiloride Cefonicid Bethanechol Arbutin Ceforanide Bicalutamide Ascorbic acid calcium salt Cefotetan Calcium glubionate Auranofin Ceftibuten Cangrelor Azacitidine Ceftolozane Capecitabine Benserazide Cerivastatin Carbamoylcholine Besifloxacin Chlortetracycline Carisoprodol beta-L-fructofuranose Cilastatin Chlorobutanol Bictegravir Citicoline Cidofovir Bismuth subgallate Cladribine Clodronic acid Bleomycin Clarithromycin Colistimethate Bortezomib Clindamycin Cyclandelate Bromotheophylline Clofarabine Dexpanthenol Calcium threonate Cromoglicic acid Edoxudine Capecitabine Demeclocycline Elbasvir Capreomycin Diaminopropanol tetraacetic acid Erdosteine Carbidopa Diazolidinylurea Ethchlorvynol Carbocisteine Dibekacin Ethinamate Carboplatin Dinoprostone Famotidine Cefotetan Dipyridamole Fidaxomicin Chlormerodrin Doripenem Flavin adenine dinucleotide -

UNIVERSITE DE NANTES Thomas Gelineau

UNIVERSITE DE NANTES __________ FACULTE DE MEDECINE __________ Année 2011 N° 139 THESE pour le DIPLÔME D’ÉTAT DE DOCTEUR EN MÉDECINE DES de médecine générale par Thomas Gelineau né le 29 janvier 1983 à Cholet __________ Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 06/12/2011 __________ LE RHUME DE L'ENFANT ET SON TRAITEMENT: DECISION PARTAGEE AVEC LES PARENTS D'APRES UN QUESTIONNAIRE __________ Président : Monsieur le Professeur Olivier MALARD Directeur de thèse : Madame le Professeur Jacqueline LACAILLE 1 Table des matières IIntroduction................................................................................................................ 7 IIDéfinition, état des connaissances...........................................................................8 1Le rhume.......................................................................................................................................8 APhysiopathologie............................................................................................................................. 8 aL'origine virale.................................................................................................................................... 8 bLa saisonnalité................................................................................................................................... 8 cL'âge de survenue.............................................................................................................................. 9 dLe sexe.................................................................................................................................................. -

Stems for Nonproprietary Drug Names

USAN STEM LIST STEM DEFINITION EXAMPLES -abine (see -arabine, -citabine) -ac anti-inflammatory agents (acetic acid derivatives) bromfenac dexpemedolac -acetam (see -racetam) -adol or analgesics (mixed opiate receptor agonists/ tazadolene -adol- antagonists) spiradolene levonantradol -adox antibacterials (quinoline dioxide derivatives) carbadox -afenone antiarrhythmics (propafenone derivatives) alprafenone diprafenonex -afil PDE5 inhibitors tadalafil -aj- antiarrhythmics (ajmaline derivatives) lorajmine -aldrate antacid aluminum salts magaldrate -algron alpha1 - and alpha2 - adrenoreceptor agonists dabuzalgron -alol combined alpha and beta blockers labetalol medroxalol -amidis antimyloidotics tafamidis -amivir (see -vir) -ampa ionotropic non-NMDA glutamate receptors (AMPA and/or KA receptors) subgroup: -ampanel antagonists becampanel -ampator modulators forampator -anib angiogenesis inhibitors pegaptanib cediranib 1 subgroup: -siranib siRNA bevasiranib -andr- androgens nandrolone -anserin serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonists altanserin tropanserin adatanserin -antel anthelmintics (undefined group) carbantel subgroup: -quantel 2-deoxoparaherquamide A derivatives derquantel -antrone antineoplastics; anthraquinone derivatives pixantrone -apsel P-selectin antagonists torapsel -arabine antineoplastics (arabinofuranosyl derivatives) fazarabine fludarabine aril-, -aril, -aril- antiviral (arildone derivatives) pleconaril arildone fosarilate -arit antirheumatics (lobenzarit type) lobenzarit clobuzarit -arol anticoagulants (dicumarol type) dicumarol -

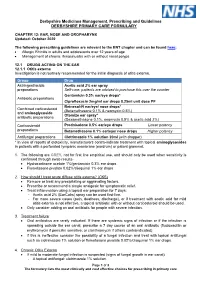

EAR, NOSE and OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020

Derbyshire Medicines Management, Prescribing and Guidelines DERBYSHIRE PRIMARY CARE FORMULARY CHAPTER 12: EAR, NOSE AND OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020 The following prescribing guidelines are relevant to the ENT chapter and can be found here: • Allergic Rhinitis in adults and adolescents over 12 years of age • Management of chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps 12.1 DRUGS ACTING ON THE EAR 12.1.1 Otitis externa Investigation is not routinely recommended for the initial diagnosis of otitis externa. Group Drug Astringent/acidic Acetic acid 2% ear spray preparations Self-care: patients are advised to purchase this over the counter Gentamicin 0.3% ear/eye drops* Antibiotic preparations Ciprofloxacin 2mg/ml ear drops 0.25ml unit dose PF Betnesol-N ear/eye/ nose drops* Combined corticosteroid (Betamethasone 0.1% & neomycin 0.5%) and aminoglycoside Otomize ear spray* antibiotic preparations (Dexamethasone 0.1%, neomycin 0.5% & acetic acid 2%) Corticosteroid Prednisolone 0.5% ear/eye drops Lower potency preparations Betamethasone 0.1% ear/eye/ nose drops Higher potency Antifungal preparations Clotrimazole 1% solution 20ml (with dropper) * In view of reports of ototoxicity, manufacturers contra-indicate treatment with topical aminoglycosides in patients with a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum) or patent grommet. 1. The following are GREY, not for first line empirical use, and should only be used when sensitivity is confirmed through swab results- • Hydrocortisone acetate 1%/gentamicin 0.3% ear drops • Flumetasone pivalate 0.02%/clioquinol 1% ear drops 2. How should I treat acute diffuse otitis externa? (CKS) • Remove or treat any precipitating or aggravating factors. • Prescribe or recommend a simple analgesic for symptomatic relief. -

Chemical Ligand Space of Cereblon Iuliia Boichenko,† Kerstin Bar,̈ Silvia Deiss, Christopher Heim, Reinhard Albrecht, Andrei N

This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. Article Cite This: ACS Omega 2018, 3, 11163−11171 http://pubs.acs.org/journal/acsodf Chemical Ligand Space of Cereblon Iuliia Boichenko,† Kerstin Bar,̈ Silvia Deiss, Christopher Heim, Reinhard Albrecht, Andrei N. Lupas, Birte Hernandez Alvarez,* and Marcus D. Hartmann* Department of Protein Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Max-Planck-Ring 5, 72076 Tübingen, Germany *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: The protein cereblon serves as a substrate receptor of a ubiquitin ligase complex that can be tuned toward different target proteins by cereblon-binding agents. This approach to targeted protein degradation is exploited in different clinical settings and has sparked the development of a growing number of thalidomide derivatives. Here, we probe the chemical space of cereblon binding beyond such derivatives and work out a simple set of chemical requirements, delineating the metaclass of cereblon effectors. We report co-crystal structures for a diverse set of compounds, including commonly used pharmaceuticals, but also find that already minimalistic cereblon-binding moieties might exert teratogenic effects in zebrafish. Our results may guide the design of a post-thalidomide generation of therapeutic cereblon effectors and provide a framework for the circumvention of unintended cereblon binding by negative design -

Ep 1553091 A1

Europäisches Patentamt *EP001553091A1* (19) European Patent Office Office européen des brevets (11) EP 1 553 091 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION published in accordance with Art. 158(3) EPC (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.7: C07D 263/32, C07D 417/14, 13.07.2005 Bulletin 2005/28 C07D 333/20, C07D 413/12, C07D 417/06 (21) Application number: 04726765.3 (86) International application number: (22) Date of filing: 09.04.2004 PCT/JP2004/005119 (87) International publication number: WO 2004/089918 (21.10.2004 Gazette 2004/43) (84) Designated Contracting States: • SAKAMOTO, Johei AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) HU IE IT LI LU MC NL PL PT RO SE SI SK TR • NAKANISHI, Hiroyuki Designated Extension States: Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) AL HR LT LV MK • NAKAGAWA, Yuichi Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) (30) Priority: 09.04.2003 JP 2003105267 • OHTA, Takeshi 03.06.2003 JP 2003157590 Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) • SAKATA, Shohei (71) Applicant: Japan Tobacco Inc. Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) Tokyo 105-8422 (JP) • MORINAGA, Hisayo Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) (72) Inventors: • IKEMOTO, Tomoyuki (74) Representative: Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) von Kreisler, Alek, Dipl.-Chem. et al • TANAKA, Masahiro Deichmannhaus am Dom, Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) Postfach 10 22 41 • YUNO, Takeo 50462 Köln (DE) Takatsuki-shi, Osaka 569-1125 (JP) (54) HETEROAROMATIC PENTACYCLIC COMPOUND AND MEDICINAL USE THEREOF (57) A 5-membered heteroaromatic ring compound represented by the formula [I] 1 2 4 5 7 wherein V is CH or N; W is S or O; R and R are each H etc.; X is -N(R )-, -O-, -S-, -SO2-N(R )-, -CO-N(R )- etc.; L is EP 1 553 091 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) (Cont. -

Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine)

Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) Description Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), used to treat pain and swelling in arthritis, belongs to a class of drugs called sulfa drugs. It is a combination of salicylate (the main ingredient in aspirin) and a sulfa antibiotic. Sulfasalazine is also known as a disease modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) because it not only decreases the pain and swelling of arthritis, but also may prevent damage to joints. In addition, it may reduce the risk of long term loss of function. Uses Sulfasalazine was first used over 70 years ago to treat rheumatoid arthritis which, at one time, was thought to be caused by a bacterial infection. Sulfasalazine was designed as a combination of an aspirin- like anti-inflammatory medicine with a sulfa containing antibiotic. While a bacterial infectious cause for rheumatoid arthritis is longer believed to be true, sulfasalazine continues to be useful for treating for mild to moderate symptoms, or may be given with other drugs for more severe symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. It is also used for other conditions, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis (also called juvenile rheumatoid arthritis), ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and ulcerative colitis. How it works Sulfasalazine treats swelling, pain, and stiffness in arthritis. However, it is not entirely clear how this medication works for rheumatoid arthritis. Dosing Sulfasalazine comes in a 500 milligram tablet, and should be taken with food and a full glass of water to prevent stomach upset. The medication is often started at low doses to treat rheumatoid arthritis, typically one to two tablets a day, to prevent side effects. After the first week, the dose may be increased slowly to the usual 2 tablets (1 gram) taken twice a day.