'Pack a More Powerful Punch'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1 The nails have several important uses, which are as they are produced and remain stored during easily appreciable when the nails are absent or growth. they lose their function. The most evident use of It is therefore important to know how the fi ngernails is to be an ornament of the hand, but healthy nail appears and how it is formed, in we must not underestimate other important func- order to detect signs of pathology and understand tions, such as the protective value of the nail plate their pathogenesis. against trauma to the underlying distal phalanx, its counterpressure effect to the pulp important for walking and for tactile sensation, the scratch- 1.1 Nail Anatomy ing function, and the importance of fi ngernails and Physiology for manipulation of small objects. The nails can also provide information about What we call “nail” is the nail plate, the fi nal part the person’s work, habits, and health status, as of the activity of 4 epithelia that proliferate and several well-known nail features are a clue to sys- differentiate in a specifi c manner, in order to form temic diseases. Abnormal nails due to biting or and protect a healthy nail plate [1 ]. The “nail onychotillomania give clues to the person’s emo- unit” (Fig. 1.1 ) is composed by: tional/psychiatric status. Nail samples are uti- • Nail matrix: responsible for nail plate production lized for forensic and toxicology analysis, as • Nail folds: responsible for protection of the several substances are deposited in the nail plate nail matrix Proximal nail fold Nail plate Fig. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Pedicure: Nail Enhancements

All Hair Services Include Shampoo All Services Based on Student Availability Long Hair is Extra & Senior Price Available Hair Cuts: Color: (Does Not Include Cut & Style) Hair Cut (Hood dryer) $6.50 Retouch/Tint/PM Shine $14.50 With Blowdry $13.50 Additional Application $8.00 With Blowdry & Flat Iron $21.50 Color (All over color) $20.00 Foils Each $4.00 Hair Styles: Hair Length to Collar $38.00 Shampoo/Set $6.75 Hair Length to Shoulder $48.00 Spiral Rod Set $20.00 Hair Length past Shoulder $58.00 Shampoo/ Blowdry $9.00 Frosting with Cap $17.50 With Thermal Iron $13.00 Men’s Comb Highlight with Cut $15.00 With Flat Iron $15.00 With Press & Curl $18.00 Perms & Relaxers: (Includes Cut & Style) Wrap Only $6.50 Regular or Normal Hair $20.95 Wrap with Roller Set $10.50 Resistant or Tinted Hair $26.00 Fingerwaves with Style $17.50 Spiral or Piggyback $36.00 Twists $3.00 Relaxer $35.00 Straight Back $20.00 Curled $15.00 Other Hair Services: Spiral $20.00 Shampoo Only $2.00 French Braids with Blowdry $15.00 Line-up $3.00 Under 10 Braids $20.00 Deep Condition $5.00 Over 10 Braids $25.00 Keratin Treatment $15.00 Braid Removal $15.00 Updo or French Roll $20.00 Manicure: Spa Manicure $9.50 Waxing: French Manicure $8.00 Brow $6.00 Manicure $6.42 Lip $5.00 Chin $5.00 Pedicure: Full Face $15.00 Spa Pedicure $20.00 Half Leg $15.00 French Pedicure $17.00 Full Leg $30.00 Pedicure $15.00 Underarm $15.00 Half Arm $10.00 Nail Enhancements: Full Arm $15.00 Shellac (French $2) $15.00 Mid Back & Up $15.00 Overlay (Natural Nail) $12.00 Full Back $25.00 Acrylic Full Set $16.50 Bikini $25.00 Gel Full Set $18.00 Fill-in Gel & Acrylic $12.00 Massages: Nail Repair( Per Nail) $2.00 Relaxation $15.00 Soak Off $3.00 Deep Tissue $19.95 Nail Art (Per Nail) $1.00 Other Nail Services: Nails & Waxing Services Taxable Polish Change $4.00 Nails Clipped $5.00 Paraffin Dip Wax $5.00 . -

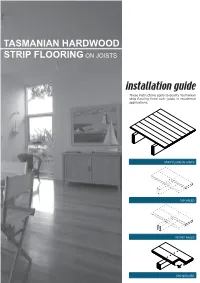

Tasmanian Hardwood Strip Flooring on Joists Guide for Installing

TASMANIAN HARDWOOD STRIP FLOORING ON JOISTS installation guide These instructions apply to quality Tasmanian strip flooring fixed over joists in residential applications. STRIP FLOOR ON JOISTS TOP NAILED SECRET NAILED END MATCHED TOOLS Simple tools are adequate in most applications. Necessary tools are: Tool Requirement Checklist Pencil, tape measure and square Hammer, punch and nail bag Stringline, spirit level and straight edge Hand saw and jig saw Safety glasses, dust mask and knee pads Spacers (about 100mm long and 2 mm thick) Rubber mallet, broom and vacuum cleaner Framing chisel For specialist applications, a drop saw, an air power staple gun, a power actuated fastener system and a cramping system may be useful. MATERIALS Use quality boards of the correct thickness. Grade descriptions for strip flooring are set out in the Australian Standard AS 2796 and are available at: www.tastimber.tas.gov.au. Boards at least 19 mm thick are needed to span 450 mm. Board width - Only secret nail boards up to 85 mm cover width. Secret nailed flooring is fixed through the tongue of specially profiled boards. Since they are only secured with one fastener per joist or batten, their width is limited to 85 mm cover. Board over 85 cover must be top nailed with two fasteners per joist. Use the correct nails for the job. The nail sizes required by Australian Standard 1684 are: Nail sizes for T & G flooring to joists* Nail sizes for T & G flooring to plywood substrate* Nailing Softwood Hardware & Strip flooring Rec. nailing (min.15mm substrate) joists cypress joists thicknes (mm) Hand 65 x 2.8 mm 50 x 2.8 mm 38 x 16 guage chisel point staples or driven bullet head bullet head 19 or 20 38 x 2.2 mm nails at 300mm spacing 32 x 16 guage chisel point staples or Machine 12,19 or 20 driven 65 x 2.5 mm 50 x 2.5 mm 30 x 2.2 mm nails at 200mm spacing *Alternative fasteners can be used for substrates types not listed subject to manufacturers’ recommendation. -

Regional Handwashing Policy

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION POLICY AND PROCEDURE POLICY INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL POLICIES EFFECTIVE DATE: SECTION: AND PROCEDURES 7/1/2014 TITLE: Hand Health & Hygiene Page: 1 of 8 BACKGROUND Studies have shown that handwashing causes a reduction in the carriage of potential pathogens on the hands. Microorganisms proliferate on the hands within the moist environment of gloves. Handwashing results in the reduction of patient morbidity and mortality from health care associated infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that handwashing is the single most important procedure for preventing health-care associated infections. Artificial nails are more likely than natural nails to harbor pathogens that can lead to health care associated infections. There are four types of hand washing (see body of policy for detailed instructions): TYPE PURPOSE METHOD Routine Handwashing To remove soil and transient Wash hands with soap and microorganisms. water for at least 15 seconds. Hand antisepsis To remove soil and remove or Wash hands with antimicrobial destroy transient soap and water for at least 15 microorganisms. seconds. Hand rub/degerming To destroy transient and Rub alcohol-based hand resident microorganisms on degermer into hands vigorously UNSOILED hands. until dry. Surgical hand scrub To remove or destroy transient Wash hands and forearms with microorganisms and reduce antimicrobial soap and water resident flora. with brush to achieve friction. Or alcohol-based preparation rubbed vigorously -

White Nail As a Static Physical Finding: Revitalization of Physical Examination

Case Report White Nail as a Static Physical Finding: Revitalization of Physical Examination Ryuichi Ohta 1,* and Chiaki Sano 2 1 Community Care, Unnan City Hospital, 699-1221 96-1 Iida, Daito-cho, Unnan 699-1221, Shimane Prefecture, Japan 2 Department of Community Medicine Management, Faculty of Medicine, Shimane University, 89-1 Enya cho, Izumo 693-8501, Shimane Prefecture, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-9050605330 Abstract: Physical examinations are critical for diagnosis and should be differentiated into static and dynamic categories. One of the static findings is white nail, such as Terry’s and Lindsay’s nails. Here, we report the cases of two older patients with acute diseases who had nail changes that aided evaluation of their clinical course. Two elderly women who presented with acute conditions were initially thought to have normal serum albumin levels. They were found to have white nail with differences in nail involvement of the first finger, which subsequently revealed their hypoalbuminemia. The clinical courses were different following the distribution of nail whitening. Our findings show that examination of a white nail could indicate the previous clinical status more clearly than laboratory data. It can be useful for evaluating preclinical conditions in patients with acute diseases. Further evaluation is needed to establish the relationship between clinical outcomes and the presence of white nail in acute conditions among older patients. Citation: Ohta, R.; Sano, C. White Keywords: Lindsay’s nail; nail findings; nutritional assessment; physical examination; Terry’s nail; Nail as a Static Physical Finding: white nail Revitalization of Physical Examination. -

Pretty Scary 2 Unmasking Toxic Chemicals in Kids’ Makeup

Prevention October 2016 Starts Here Campaign for Safe Cosmetics Pretty Scary 2 Unmasking toxic chemicals in kids’ makeup breastcancerfund.org 1 Acknowledgements Developed and published by the Breast Cancer Fund and spearheaded by their Campaign for Safe Cosmetics, this report was written by Connie Engel, Ph.D.; Janet Nudelman, MA; Sharima Rasanayagam, Ph.D.; Maija Witte, MPH; and Katie Palmer. Editing, messaging and vision were contributed by Denise Halloran and Erika Wilhelm. Sara Schmidt, MPH, MSW, coordinated the purchasing of products reviewed in this report and worked closely with partners to share the message. Thank you to James Consolantis, our contributing content specialist and Rindal&Co for design direction. WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR THE GENEROUS CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OUR FUNDERS: As You Sow Foundation, Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation, Lisa and Douglas Goldman Foundation, Park Foundation, Passport Foundation, and the Serena Foundation. breastcancerfund.org 2 Our partners in purchasing products Pam Miller, Alaska Community Action on Toxics, Alaska Brooke Sarmiento, BEE-OCH Organics, Colorado Sara Schmidt, Breast Cancer Fund, California Susan Eastwood, Clean Water Action, Connecticut Anne Hulick, Clean Water Action, Connecticut Johnathan Berard, Clean Water Action, Rhode Island Lauren Carson, Clean Water Action, Rhode Island Cindy Luppi, Clean Water Action, Massachusetts Kadineyse Ramize Peña, Clean Water Action, Massachusetts Elizabeth Saunders, Clean Water Action, Massachusetts Sara Lamond, Fig & Flower, Georgia Beverly Johnson, -

Management of Ingested Foreign Bodies in Children: a Clinical Report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee

COMMITTEE COMMENTARY Management of Ingested Foreign Bodies in Children: A Clinical Report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee ÃRobert E. Kramer, yDiana G. Lerner, zTom Lin, §Michael Manfredi, jjManoj Shah, ôThomas C. Stephen, #Troy E. Gibbons, ÃÃHarpreet Pall, yyBen Sahn, zzMark McOmber, §§George Zacur, ÃJoel Friedlander, jjjjAntonio J. Quiros, ôôDouglas S. Fishman, and ##Petar Mamula ABSTRACT ingestion. Furthermore, changes in the types of ingestions encountered, Foreign body ingestions in children are some of the most challenging clinical specifically button batteries and high-powered magnet ingestions, create scenarios facing pediatric gastroenterologists. Determining the indications an even greater potential for severe morbidity and mortality among and timing for intervention requires assessment of patient size, type of object children. As a result, clinical guidelines regarding management of these ingested, location, clinical symptoms, time since ingestion, and myriad other ingestions in children remain varied and sporadic, with little in the way of factors. Often the easiest and least anxiety-producing decision is the one to prospective data to guide their development. An expert panel of pediatric proceed to endoscopic removal, instead of observation alone. Because of endoscopists was convened and produced the present article that outlines variability in pediatric patient size, there are less firm guidelines available to practical clinical approaches to the pediatric patient with a variety of determine which type of object will safely pass, as opposed to the clearer foreign body ingestions. This guideline is intended as an educational tool guidelines in the adult population. In addition, the imprecise nature of the that may help inform pediatric endoscopists in managing foreign body ingestions in children. -

The Older Woman with Vulvar Itching and Burning Disclosures Old Adage

Disclosures The Older Woman with Vulvar Mark Spitzer, MD Itching and Burning Merck: Advisory Board, Speakers Bureau Mark Spitzer, MD QiagenQiagen:: Speakers Bureau Medical Director SABK: Stock ownership Center for Colposcopy Elsevier: Book Editor Lake Success, NY Old Adage Does this story sound familiar? A 62 year old woman complaining of vulvovaginal itching and without a discharge self treatstreats with OTC miconazole.miconazole. If the only tool in your tool Two weeks later the itching has improved slightly but now chest is a hammer, pretty she is burning. She sees her doctor who records in the chart that she is soon everyyggthing begins to complaining of itching/burning and tells her that she has a look like a nail. yeast infection and gives her teraconazole cream. The cream is cooling while she is using it but the burning persists If the only diagnoses you are aware of She calls her doctor but speaks only to the receptionist. She that cause vulvar symptoms are Candida, tells the receptionist that her yeast infection is not better yet. The doctor (who is busy), never gets on the phone but Trichomonas, BV and atrophy those are instructs the receptionist to call in another prescription for teraconazole but also for thrthreeee doses of oral fluconazole the only diagnoses you will make. and to tell the patient that it is a tough infection. A month later the patient is still not feeling well. She is using cold compresses on her vulva to help her sleep at night. She makes an appointment. The doctor tests for BV. -

Anatomy and Physiology of the Nail

Anatomy and physiology of the nail Christian Dumontier Institut de la Main & hôpital saint Antoine, Paris Anatomy of the nail • The osteo-ligamentous support • Nail plate • All surrounding tissues, i.e. the perionychium The distal phalanx • Is reinforced laterally by the the Flint’s ligament • Which protect the neuro-vascular structures Flint’s ligament The ligamentous support • The nail is fixed onto the bone through a highly vascularized dermis • The nail is fixed onto the bone through two strong ligaments The ligamentous structures • All the ligaments merge together with • The extensor tendon • The flexor tendon • The collateral ligaments • Flint’s ligament • Guero’s dorsal ligament • (Hyponychial ligament) Clinical implications • A normal nail cannot grow on an abnormal support +++ • Large phalanx = racket nails • bony malunion = nail dystrophy • arthrosis = Pincer nail,... The nail plate • Is produced by the germinal matrix • ItsKeratinic shape depends structure, on the bonypartiall supporty transparent and the and integritycurved both of the longitudinall soft-tissuesy arandound transv it ersally • Three different layers • 0,5 mm thickness, 20% of water Clinical applications • The nail plate is often intact in crushing trauma due to its flexibility • And must be removed in order to explore all the lesions +++ The perionychium • Include all the soft- tissues located under the nail plate • Nail (germinal) matrix, • Nail bed, • Hyponychium The perionychium • Soft-tissues aroud the plate (paronychium) proximal and lateral nail wall (fold) -

Footcare Update Expert Care from Professionals Who Care

FootCare Update Expert care from professionals who care. Volume III, No. 6; Revised Winter, 2006 Patients and their Physicians always benefit when.... DPM’s provide a simple, permanent solution to correct painful or infected ingrown nails. normal skin flora and setting up a ail structure (an inherited char- nidus for infection. acteristic), combined with nor- N 3) Infection (Pyogenic Granuloma) mal shoe gear, is the source of identifies reactive inflammatory tis- ingrown nail pain and/or infection. sue, the result of indwelling of the “Contrary to popular belief, ingrown source of irritation (the nail plate). nails are not a product of incorrect Over 99% of all hypertrophic tissue nail cutting,” said Kenneth Leavitt, identified as pyogenic granuloma is D.P.M., of Brookline, MA. benign and will atrophy upon removal The prevalence of ingrown nails is of the offending nail plate and resolu- highest when individuals wear shoes, tion of the infection with antibiotics. regardless of race, gender or country Pre-Op: Typical incurved nail plate bor- Very rarely will a chronic granuloma of origin. der (left) with infection. become basal or squamous cell carci- The painful or infected ingrown noma. “Reconstruction of chronic nail condition usually affects the great done on each of his great toes. hypertrophic tissue is rarely neces- toe, but also can affect lesser digits. Avulsion does resolve the problem temporarily, but the nail always grows sary,” Leavitt said. Traditional Treatment Ineffective back thicker and more incurvated, due Quick Surgery Best Treatment Ingrown nail treatment, sadly, is to trauma incurred to the nail matrix. for 95% of Patients still anecdotal throughout most of the Removing the offending portion of world, according to Dr. -

9 Nail Problems You Shouldn't Ignore

menshealth.com http://www.menshealth.com/health/nail-problems-you-shouldnt-ignore 9 Nail Problems You Shouldn’t Ignore Next Your eyes may offer a glimpse of your soul—but for a view of your internal organs, check your fingers and toes instead. “Your nails can tell a tremendous amount of information about your general health,” says Dana Stern, M.D., a dermatologist and nail specialist in New York City. “Certain nail changes can indicate issues with the kidneys, infections of the heart, anemia, lung disease, and even exposure to certain poisons.” That’s because diseases that affect your whole body can change the blood flow, growth patterns, or shape of your fingernails and toenails in ways you may notice long before any other symptoms, says Chris Adigun, M.D., a board certified dermatologist and nail specialist in Chapel Hill, N.C. So if you spy something new or unusual on the ends of your digits, check in with your primary care doctor or a dermatologist, she advises. Treating the underlying condition often can save your nails—and maybe even your life. Advertisement Daily Dose You may unsubscribe at any time. menshealth.com http://www.menshealth.com/health/nail-problems-you-shouldnt-ignore/1-koilonychia-or-spoon-nails 9 Nail Problems You Shouldn’t Ignore 1. Koilonychia or “spoon nails" PrevNext You could hold a drop of liquid inside these nails’ concave shape, says Al D’Angelantonio III, D.P.M., who sees and treats toenail problems as a foot and ankle surgeon at Penn Medicine. Spoon nails can serve as a red flag for iron- deficiency anemia, low blood oxygen levels from not taking in or absorbing enough iron.