Management of Ingested Foreign Bodies in Children: a Clinical Report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1 The nails have several important uses, which are as they are produced and remain stored during easily appreciable when the nails are absent or growth. they lose their function. The most evident use of It is therefore important to know how the fi ngernails is to be an ornament of the hand, but healthy nail appears and how it is formed, in we must not underestimate other important func- order to detect signs of pathology and understand tions, such as the protective value of the nail plate their pathogenesis. against trauma to the underlying distal phalanx, its counterpressure effect to the pulp important for walking and for tactile sensation, the scratch- 1.1 Nail Anatomy ing function, and the importance of fi ngernails and Physiology for manipulation of small objects. The nails can also provide information about What we call “nail” is the nail plate, the fi nal part the person’s work, habits, and health status, as of the activity of 4 epithelia that proliferate and several well-known nail features are a clue to sys- differentiate in a specifi c manner, in order to form temic diseases. Abnormal nails due to biting or and protect a healthy nail plate [1 ]. The “nail onychotillomania give clues to the person’s emo- unit” (Fig. 1.1 ) is composed by: tional/psychiatric status. Nail samples are uti- • Nail matrix: responsible for nail plate production lized for forensic and toxicology analysis, as • Nail folds: responsible for protection of the several substances are deposited in the nail plate nail matrix Proximal nail fold Nail plate Fig. -

Mississippi Teacher's Perspectives of Danielson's Framework for Teaching

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2018 Mississippi Teacher's Perspectives of Danielson's Framework for Teaching Donna Floyd University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Floyd, Donna, "Mississippi Teacher's Perspectives of Danielson's Framework for Teaching" (2018). Dissertations. 1574. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1574 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MISSISSIPPI TEACHER’S PERSPECTIVES ON DANIELSON’S FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING by Donna Crosby Floyd A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Education and Human Sciences and the School of Education at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. David Lee, Committee Chair Dr. Sharon Rouse Dr. Kyna Shelley Dr. Richard Mohn ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. David Lee Dr. Lillian Hill Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School December 2018 COPYRIGHT BY Donna Crosby Floyd 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT The focus of this study was to measure Mississippi teacher’s perspectives as identified in the Teacher’s Perspectives on Danielson’s Framework for Teaching (TPDFT) instrument. This quantitative study investigated whether or not statistically significant differences existed between domains as identified in the TPDFT, and if these findings differed statistically as a function of years of teaching experience, type of Mississippi teaching certification, and degree of professional trust. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

50 Years in Rock History

HISTORY AEROSMITH 50 YEARS IN ROCK PART THREE AEROSMITH 50 YEARS IN ROCK PART THREE 1995–1999 The year of 1995 is for AEROSMITH marked by AEROSMITH found themselves in a carousel the preparations of a new album, in which the of confusions, intrigues, great changes, drummer Joey Kramer did not participate in its termination of some collaboration, returns first phase. At that time, he was struggling with and new beginnings. They had already severe depressive states. After the death of his experienced all of it many times during their father, everything that had accumulated inside career before, but this time on a completely him throughout his life and could no longer be different level. The resumption of collaboration ignored, came to the surface. Unsuspecting and with their previous record company was an 2,000 miles away from the other members of encouragement and a guarantee of a better the band, he undergoes treatment. This was tomorrow for the band while facing unfavorable disrupted by the sudden news of recording circumstances. The change of record company the basics of a new album with a replacement was, of course, sweetened by a lucrative drummer. Longtime manager Tim Collins handled offer. Columbia / Sony valued AEROSMITH the situation in his way and tried to get rid of at $ 30 million and offered the musicians Joey Kramer without the band having any idea a contract that was certainly impossible about his actions. In general, he tried to keep the to reject. AEROSMITH returned under the musicians apart so that he had everything under wing of a record company that had stood total control. -

Pedicure: Nail Enhancements

All Hair Services Include Shampoo All Services Based on Student Availability Long Hair is Extra & Senior Price Available Hair Cuts: Color: (Does Not Include Cut & Style) Hair Cut (Hood dryer) $6.50 Retouch/Tint/PM Shine $14.50 With Blowdry $13.50 Additional Application $8.00 With Blowdry & Flat Iron $21.50 Color (All over color) $20.00 Foils Each $4.00 Hair Styles: Hair Length to Collar $38.00 Shampoo/Set $6.75 Hair Length to Shoulder $48.00 Spiral Rod Set $20.00 Hair Length past Shoulder $58.00 Shampoo/ Blowdry $9.00 Frosting with Cap $17.50 With Thermal Iron $13.00 Men’s Comb Highlight with Cut $15.00 With Flat Iron $15.00 With Press & Curl $18.00 Perms & Relaxers: (Includes Cut & Style) Wrap Only $6.50 Regular or Normal Hair $20.95 Wrap with Roller Set $10.50 Resistant or Tinted Hair $26.00 Fingerwaves with Style $17.50 Spiral or Piggyback $36.00 Twists $3.00 Relaxer $35.00 Straight Back $20.00 Curled $15.00 Other Hair Services: Spiral $20.00 Shampoo Only $2.00 French Braids with Blowdry $15.00 Line-up $3.00 Under 10 Braids $20.00 Deep Condition $5.00 Over 10 Braids $25.00 Keratin Treatment $15.00 Braid Removal $15.00 Updo or French Roll $20.00 Manicure: Spa Manicure $9.50 Waxing: French Manicure $8.00 Brow $6.00 Manicure $6.42 Lip $5.00 Chin $5.00 Pedicure: Full Face $15.00 Spa Pedicure $20.00 Half Leg $15.00 French Pedicure $17.00 Full Leg $30.00 Pedicure $15.00 Underarm $15.00 Half Arm $10.00 Nail Enhancements: Full Arm $15.00 Shellac (French $2) $15.00 Mid Back & Up $15.00 Overlay (Natural Nail) $12.00 Full Back $25.00 Acrylic Full Set $16.50 Bikini $25.00 Gel Full Set $18.00 Fill-in Gel & Acrylic $12.00 Massages: Nail Repair( Per Nail) $2.00 Relaxation $15.00 Soak Off $3.00 Deep Tissue $19.95 Nail Art (Per Nail) $1.00 Other Nail Services: Nails & Waxing Services Taxable Polish Change $4.00 Nails Clipped $5.00 Paraffin Dip Wax $5.00 . -

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

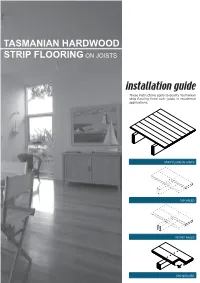

Tasmanian Hardwood Strip Flooring on Joists Guide for Installing

TASMANIAN HARDWOOD STRIP FLOORING ON JOISTS installation guide These instructions apply to quality Tasmanian strip flooring fixed over joists in residential applications. STRIP FLOOR ON JOISTS TOP NAILED SECRET NAILED END MATCHED TOOLS Simple tools are adequate in most applications. Necessary tools are: Tool Requirement Checklist Pencil, tape measure and square Hammer, punch and nail bag Stringline, spirit level and straight edge Hand saw and jig saw Safety glasses, dust mask and knee pads Spacers (about 100mm long and 2 mm thick) Rubber mallet, broom and vacuum cleaner Framing chisel For specialist applications, a drop saw, an air power staple gun, a power actuated fastener system and a cramping system may be useful. MATERIALS Use quality boards of the correct thickness. Grade descriptions for strip flooring are set out in the Australian Standard AS 2796 and are available at: www.tastimber.tas.gov.au. Boards at least 19 mm thick are needed to span 450 mm. Board width - Only secret nail boards up to 85 mm cover width. Secret nailed flooring is fixed through the tongue of specially profiled boards. Since they are only secured with one fastener per joist or batten, their width is limited to 85 mm cover. Board over 85 cover must be top nailed with two fasteners per joist. Use the correct nails for the job. The nail sizes required by Australian Standard 1684 are: Nail sizes for T & G flooring to joists* Nail sizes for T & G flooring to plywood substrate* Nailing Softwood Hardware & Strip flooring Rec. nailing (min.15mm substrate) joists cypress joists thicknes (mm) Hand 65 x 2.8 mm 50 x 2.8 mm 38 x 16 guage chisel point staples or driven bullet head bullet head 19 or 20 38 x 2.2 mm nails at 300mm spacing 32 x 16 guage chisel point staples or Machine 12,19 or 20 driven 65 x 2.5 mm 50 x 2.5 mm 30 x 2.2 mm nails at 200mm spacing *Alternative fasteners can be used for substrates types not listed subject to manufacturers’ recommendation. -

Regional Handwashing Policy

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION POLICY AND PROCEDURE POLICY INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL POLICIES EFFECTIVE DATE: SECTION: AND PROCEDURES 7/1/2014 TITLE: Hand Health & Hygiene Page: 1 of 8 BACKGROUND Studies have shown that handwashing causes a reduction in the carriage of potential pathogens on the hands. Microorganisms proliferate on the hands within the moist environment of gloves. Handwashing results in the reduction of patient morbidity and mortality from health care associated infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that handwashing is the single most important procedure for preventing health-care associated infections. Artificial nails are more likely than natural nails to harbor pathogens that can lead to health care associated infections. There are four types of hand washing (see body of policy for detailed instructions): TYPE PURPOSE METHOD Routine Handwashing To remove soil and transient Wash hands with soap and microorganisms. water for at least 15 seconds. Hand antisepsis To remove soil and remove or Wash hands with antimicrobial destroy transient soap and water for at least 15 microorganisms. seconds. Hand rub/degerming To destroy transient and Rub alcohol-based hand resident microorganisms on degermer into hands vigorously UNSOILED hands. until dry. Surgical hand scrub To remove or destroy transient Wash hands and forearms with microorganisms and reduce antimicrobial soap and water resident flora. with brush to achieve friction. Or alcohol-based preparation rubbed vigorously -

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963 Compiled and Edited by Stephen Coester '63 Dedicated to the Twenty-Eight Classmates Who Died in the Line of Duty ............ 3 Vietnam Stories ...................................................................................................... 4 SHOT DOWN OVER NORTH VIETNAM by Jon Harris ......................................... 4 THE VOLUNTEER by Ray Heins ......................................................................... 5 Air Raid in the Tonkin Gulf by Ray Heins ......................................................... 16 Lost over Vietnam by Dick Jones ......................................................................... 23 Through the Looking Glass by Dave Moore ........................................................ 27 Service In The Field Artillery by Steve Jacoby ..................................................... 32 A Vietnam story from Peter Quinton .................................................................... 64 Mike Cronin, Exemplary Graduate by Dick Nelson '64 ........................................ 66 SUNK by Ray Heins ............................................................................................. 72 TRIDENTS in the Vietnam War by A. Scott Wilson ............................................. 76 Tale of Cubi Point and Olongapo City by Dick Jones ........................................ 102 Ken Sanger's Rescue by Ken Sanger ................................................................ 106 -

Lida Husik Ida Husik First Began Recording in Bozo Was More Spooky Than Joyride

I'/ The Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus, for May 11th through May 17th, 1995 MATT MATT RAGLAND/Dailj Nexut 2A Thursday, May 11,1995 ____________ _________________________________ ______________ ____________ Daily Nexus aAChune Tunes ates sounds and woids Chuñe Chune? What is a know, Chune is a band out chime? I don’t think I’ll of San Diego that is as low- that throw its listeners for Burnt a loop. Even the simple al H eadhunter ever decipher the meaning pro and obscure as their of this word, but as far as I name implies. Chune cre- bum cover adds to their mystery, seemingly urging U the listener on to find an swers in the music itself The Multicultural Center Presents rather than in the glitz that normally surrounds a new band. Chune’s music does ^ o u ate cot&iallif invited to ail the talking. With guitar-driven angst backed by deep Chune shares the same is created, as all members An Opening Reception drumming, Chune label with several other play in rhythm with one searches out an identity of noteworthy San Diego another, they deconstruct Authentic History Window Open To Mornings its own in the stucco bands: Drive Like Jehu, what they’ve built up. It’s a monotony of Southern Three Mile Pilot and an Art Exhibit by an Art Exhibit byjam ila Arous-Ayoub simple plan which allows Betty Lee California. Their debut al Rocket From the Crypt. for creative interpretations Betty tee is a Chinese American artist whose Jamila Arous-Ayoub is a painter from Tunisia and a bum, Burnt, is a hard-to- And they seem to draw of rock music. -

White Nail As a Static Physical Finding: Revitalization of Physical Examination

Case Report White Nail as a Static Physical Finding: Revitalization of Physical Examination Ryuichi Ohta 1,* and Chiaki Sano 2 1 Community Care, Unnan City Hospital, 699-1221 96-1 Iida, Daito-cho, Unnan 699-1221, Shimane Prefecture, Japan 2 Department of Community Medicine Management, Faculty of Medicine, Shimane University, 89-1 Enya cho, Izumo 693-8501, Shimane Prefecture, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-9050605330 Abstract: Physical examinations are critical for diagnosis and should be differentiated into static and dynamic categories. One of the static findings is white nail, such as Terry’s and Lindsay’s nails. Here, we report the cases of two older patients with acute diseases who had nail changes that aided evaluation of their clinical course. Two elderly women who presented with acute conditions were initially thought to have normal serum albumin levels. They were found to have white nail with differences in nail involvement of the first finger, which subsequently revealed their hypoalbuminemia. The clinical courses were different following the distribution of nail whitening. Our findings show that examination of a white nail could indicate the previous clinical status more clearly than laboratory data. It can be useful for evaluating preclinical conditions in patients with acute diseases. Further evaluation is needed to establish the relationship between clinical outcomes and the presence of white nail in acute conditions among older patients. Citation: Ohta, R.; Sano, C. White Keywords: Lindsay’s nail; nail findings; nutritional assessment; physical examination; Terry’s nail; Nail as a Static Physical Finding: white nail Revitalization of Physical Examination. -

Chapter 1: Introduction 1

TATE STREET, THAT GREAT STREET: CULTURE, COMMUNITY, AND MEMORY IN GREENSBORO, NORTH CAROLINA by Ian Christian Pasquini A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2015 Approved by: ____________________________ Dr. Aaron Shapiro ____________________________ Dr. John Cox ____________________________ Dr. Dan Dupre ii ©2015 Ian Pasquini ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT IAN CHRISTIAN PASQUINI. Tate Street, That Great Street: Culture, Community, and Memory in Greensboro, North Carolina (Under the direction of DR. AARON SHAPIRO) Tate Street represents a cultural center in Greensboro, North Carolina. This work outlines the varying social groups, organizations, and institutions that defined Tate Street’s cultural identity between 1960 and 1990. Tate’s venues and spaces acted as backdrops to the cultural shifts on Tate Street. Three venues act as subjects through which to research Tate Street. Through a collection of interviews, art, video, magazines, newspapers, and pictures, this work connects with historical memory to outline Tate’s local and national historical significance. The work connects with a historical documentary made up of interviews as well as primary source materials to engage with Tate’s historical actors. iv DEDICATION Engaging with Tate’s history required the dedication of a small village of interested parties. I would be remiss in not thanking Tate’s community at large – many people have offered both their time and energy to assisting this project and will remain unheralded. This work is a reflection of the strength of Tate’s community which has both inspired and welcomed my inquiries.