Activist Literacy and Dr. Jill Stein's 2012 Green Party Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amended Canvass Ofresults General Election November 6, 2012

STATE OF ALABAMA Amended Canvass ofResults General Election November 6, 2012 Pursua:lt to Chapter 14 of Title 17 of the Code of Alabama, 1975, we, the undersigned, hereby am\~nd the canvass of results certified on November 28, 2012, for the General Election for the offices of President of the United States and Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court held in Alabama on Tuesday, November 6, 2012, and to incorporate the write-in votes reported by Wilcox County in said election. The amended canvass shows the correct tabulation of votes to be as recorded on the following pages. In Testimony Whereby, I have hereunto set my hand and affIxed the Great and Principal Seal of the State of Alal:>ama at the State Capitol, in the City nf Montgomery, on this the 17th day of December, in the year 2012 Governor Attorney General ~an~ Secretary of State FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES BARACK OBAMA / Min ROMNEY / VIRGIL H. GOODE, JR. / GARY JOHNSON / JILL STEIN / JOE BIDEN (D) PAUL RYAN (R) JAMES CLYMER (I) JIM GRAY (I) CHERI HONKALA (I) WI Total Vote County Total Votes Total Votes Total Votes Total Votes Total Votes Total Votes Total Votes Autauga 6,363 17,379 31 137 22 41 23,973 Baldwin 18,424 66,016 122 607 169 153 85,491 Barbour 5,912 5,550 9 32 6 8 11,517 Bibb 2,202 6,132 13 38 9 26 8,420 Blount 2,970 20,757 59 170 50 54 24,060 Bullock 4,061 1,251 4 3 3 5,322 Butler 4,374 5,087 9 20 6 6 9,502 Calhoun 15,511 30,278 85 291 92 107 46,364 Chambers 6,871 7,626 21 78 15 18 14,629 Cherokee 2,132 7,506 36 79 26 13 9,792 Chilton 3,397 -

June 2004 GPCA Plenary June 5-6, 2004 Sacramento City College, Sacramento, CA

June 2004 GPCA Plenary June 5-6, 2004 Sacramento City College, Sacramento, CA Saturday Morning - 6/5/04 Delegate Orientation Ellen Maisen: Review of consensus-seeking process Reminder of why we seek consensus vs. simply voting: Voting creates factions, while consensus builds community spirit. Facilitators: Magali Offerman, Jim Shannon Notes: Adrienne Prince and Don Eichelberger (alt.) Vibes: Leslie Dinkin, Don Eichelberger Time Keeper: Ed Duliba Confirming of Agenda Ratification of minutes, discussion of electoral reform, and platform plank have all been moved to Sunday. Time-sensitive agenda items were given priority. Consent Calendar Jo Chamberlain, SMC: Media bylaws concerns will also be discussed Sunday a.m. Clarification on “point of process” for Consent Calendar: when concerns are brought up, the item in question becomes dropped from the calendar and can be brought up for discussion and voting later in the plenary as time allows. I. GPUS Post-First-Round Ballot Voting Instructions Proposal - Nanette Pratini, Jonathan Lundell, Jim Stauffer Regarding convention delegate voting procedure: “If a delegate’s assigned candidate withdraws from the race or if subsequent votes are required…delegates will vote using their best judgment…as to what the voters who selected their assigned candidate would choose.” Floor rules in process of being approved by national CC. Will be conducted as a series of rounds, announced state by state. For first round, delegates are tied to the candidates as represented in the primary. If someone wins and does not want to accept the vote, subsequent rounds will vote. If a willing candidate gets a majority, they will be nominated, If “no candidate” (an option) wins, there will be an IRV election for an endorsement instead of a nomination. -

Car Crashes Into Home

L “Jones County’s Hometown Newspaper” 75¢ E R U A L EADER ALL L TO SUBSCRIBE CALL 601-649-9388 -C www.leader-call.net TUESDAY: NOVEMBER 6, 2012 CAST YOUR VOTE TODAY! Car crashes into home Boy, 4, airlifted after crash on Lower Myrick Road A 4-year-old boy suffered life-threatening injuries and a 2-year-old girl suffered only minor injuries when their mother crashed her SUV on Lower Myrick Road on Saturday afternoon. Maria Rayner, 35, of Ellisville was traveling east on At approximately 12:30 on Monday, an unidentified black male veered off the road and crashed into Lower Myrick Road, near the intersection of Reid Road, the rental home of Elizabeth Rogers at 2813 Audobon Drive in Laurel. According to LFD Chief David when she ran off the road in her 1998 Chevrolet Blazer, Chancellor, a witness who was driving behind the victim at the time of the accident reported that the jerked the wheel and flipped “three or four times,” driver slumped over before running off the road. When paramedics arrived, the driver was unrespon- according to witnesses. Her 4-year-old son, Domenic sive and taken to the emergency room at SCRMC. Christopher, was ejected through the back window and had to be airlifted to a Jackson hospital while her 2-year- old daughter, Jody Nicole, who was in a car seat, suf- fered what were described as minor injuries. Local black pastors vote for Obama in spite “I saw the boy come out the back window,” said one witness, speaking on the condition of anonymity. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Taker GREEN PARTY of CALIFORNIA June 2017 General

Mimi Newton, Sacramento GA Note- Taker GREEN PARTY OF CALIFORNIA June 2017 General Assembly Minutes Sacramento, June 17-18, 2017 ATTENDEES: Name County Sacramento Delegate status Present/Absent Brett Dixon Alameda Delegate P Greg Jan Alameda Delegate P James McFadden Alameda Not delegate P Jan Arnold Alameda Delegate P Laura Wells Alameda Delegate P Maxine Daniel Alameda Delegate P Michael Rubin Alameda Delegate P Pam Spevack Alameda Delegate P Paul Rea Alameda Delegate P Phoebe Sorgen Alameda Delegate P Erik Rydberg Butte Delegate P Bert Heuer Contra Costa Not delegate P Brian Deckman Contra Costa Not delegate P Meleiza Figueroa Contra Costa Not delegate P Tim Laidman Contra Costa Delegate P Megan Buckingham Fresno Delegate P David Cobb Humboldt Delegate/Alt P Jim Smith Humboldt Delegate P Kelsey Reedy Humboldt Not delegate P Kyle Dust Humboldt Delegate P Matt Smith-Caggiano Humboldt Delegate/Alt P Cassidy Sheppard Kern Delegate P Penny Sheppard Kern Delegate P Ajay Rai Los Angeles Delegate P Andrea Houtman Los Angeles Not delegate P Angel Orellana Los Angeles Delegate P Angelina Saucedo Los Angeles Delegate P Cesar Gonzalez Los Angeles Not delegate P Christopher Cruz Los Angeles Delegate P Daniel Mata Los Angeles Delegate P Doug Barnett Los Angeles Delegate P Fernando Ramirez Los Angeles Delegate P James Lauderdale Los Angeles Not delegate P Jimmy Rivera Los Angeles Delegate P Kenneth Mejia Los Angeles Delegate P Lisa Salvary Los Angeles Delegate P Liz Solis Los Angeles Delegate P Marla Bernstein Los Angeles Delegate P Martin Conway -

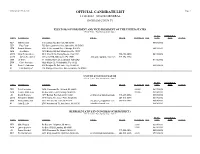

OFFICIAL CANDIDATE LIST Page 1 11/06/2012 - STATE GENERAL INGHAM COUNTY

09/14/2012 9:33:26 AM OFFICIAL CANDIDATE LIST Page 1 11/06/2012 - STATE GENERAL INGHAM COUNTY ELECTORS OF PRESIDENT AND VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES 4 Year Term - Vote for not more than 1 FILING WITHDRAWAL PARTY CANDIDATE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PETITIONS FEE DATE DATE STATUS REP Mitt Romney 3 S Cottage Rd, Belmont, Ma 02478 09/08/2012 REP Paul Ryan 700 Saint Lawrence Ave, Janesville, Wi 53545 DEM Barack Obama 5046 S Greenwood Ave, Chicago, Il 60615 09/09/2012 DEM Joe Biden 1209 Barley Mill Rd, Wilmington, De 19807 USTX Virgil H. Goode Jr. 90 E. Church St, Rocky Mount, Va 24151 540-483-9030 06/18/2012 USTX James N. Clymer 301 Letort Rd, Millersville, Pa 17551 [email protected] 717-872-6692 GRN Jill Stein 17 Trotting Horse Ln, Lexington, Ma 02421 07/16/2012 GRN Cheri Honkala 1928 Mutter St, Philadelphia, Pa 19122 NL Ross C. Anderson 418 Douglas St, Salt Lake City, Ut 84102 08/08/2012 NL Luis Rodriguez 716 Orange Grove Ave, San Fernando, Ca 91340 UNITED STATES SENATOR 6 Year Term - Vote for not more than 1 FILING WITHDRAWAL PARTY CANDIDATE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PETITIONS FEE DATE DATE STATUS REP Pete Hoekstra 1454 Cimmoran Dr, Holland, Mi 49423 22,000 04/17/2012 DEM Debbie Stabenow Po Box 4945, East Lansing, Mi 48826 30,000 05/14/2012 LIB Scotty Boman 4877 Balfour Rd, Detroit, Mi 48224 [email protected] 313-247-2052 06/04/2012 USTX Richard A. Matkin 30 W Harry Ave, Hazel Park, Mi 48030 248-515-3078 06/18/2012 GRN Harley Mikkelson 3122 W Caro Rd, Caro, Mi 48723 [email protected] 989-673-7883 06/04/2012 NL John D. -

Kings President Vice President Citywide Recap

Statement and Return Report for Certification General Election - 11/06/2012 Kings County - All Parties and Independent Bodies President/Vice President Citywide Vote for 1 Page 1 of 14 BOARD OF ELECTIONS Statement and Return Report for Certification IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK General Election - 11/06/2012 PRINTED AS OF: Kings County 7/2/2013 2:58:08PM All Parties and Independent Bodies President/Vice President (Citywide), vote for 1 Assembly District 41 PUBLIC COUNTER 32,836 EMERGENCY 2 ABSENTEE/MILITARY 899 FEDERAL 346 SPECIAL PRESIDENTIAL 0 AFFIDAVIT 3,207 Total Ballots 37,290 Less - Inapplicable Federal/Special Presidential Ballots 0 Total Applicable Ballots 37,290 BARACK OBAMA / JOE BIDEN (DEMOCRATIC) 23,385 MITT ROMNEY / PAUL RYAN (REPUBLICAN) 12,012 MITT ROMNEY / PAUL RYAN (CONSERVATIVE) 917 BARACK OBAMA / JOE BIDEN (WORKING FAMILIES) 425 JILL STEIN / CHERI HONKALA (GREEN) 139 PETA LINDSAY / YARI OSORIO (SOCIALISM & LIB) 7 GARY JOHNSON / JAMES P. GRAY (LIBERTARIAN) 158 VIRGIL GOODE / JIM CLYMER (CONSTITUTION) 22 ROSS C. ANDERSON (WRITE-IN) 1 STEPHEN DURHAM (WRITE-IN) 2 UNATTRIBUTABLE WRITE-IN (WRITE-IN) 33 Total Votes 37,101 Unrecorded 189 Assembly District 42 PUBLIC COUNTER 32,019 EMERGENCY 2 ABSENTEE/MILITARY 826 FEDERAL 402 SPECIAL PRESIDENTIAL 0 AFFIDAVIT 4,275 Total Ballots 37,524 Less - Inapplicable Federal/Special Presidential Ballots 0 Total Applicable Ballots 37,524 BARACK OBAMA / JOE BIDEN (DEMOCRATIC) 32,288 MITT ROMNEY / PAUL RYAN (REPUBLICAN) 3,694 MITT ROMNEY / PAUL RYAN (CONSERVATIVE) 438 BARACK OBAMA / JOE BIDEN (WORKING FAMILIES) 668 JILL STEIN / CHERI HONKALA (GREEN) 147 PETA LINDSAY / YARI OSORIO (SOCIALISM & LIB) 8 GARY JOHNSON / JAMES P. -

2014 Green Party Platform

Platform 2014 Green Party of the United States Approved by the Green National Committee July 2014 About the Green Party The Green Party of the United States is a federation of state Green Parties. Committed to environmentalism, non-violence, social justice and grassroots organizing, Greens are renewing democracy without the support of corporate donors. Greens provide real solutions for real problems. Whether the issue is universal health care, corporate globalization, alternative energy, election reform or decent, living wages for workers, Greens have the courage and independence necessary to take on the powerful corporate interests. The Federal Elec - tions Commission recognizes the Green Party of the United States as the official Green Party National Com - mittee. We are partners with the European Federation of Green Parties and the Federation of Green Parties of the Americas. The Green Party of the United States was formed in 2001 from of the older Association of State Green Parties (1996-2001). Our initial goal was to help existing state parties grow and to promote the formation of parties in all 51 states and colonies. Helping state parties is still our primary goal. As the Green Party National Com - mittee we will devote our attention to establishing a national Green presence in politics and policy debate while continuing to facilitate party growth and action at the state and local level. Green Party growth has been rapid since our founding and Green candidates are winning elections through - out the United States. State party membership has more than doubled. At the 2000 Presidential Nominating Convention we nominated Ralph Nader and Winona LaDuke for our Presidential ticket. -

2010 Green Party Platform

Platform 2010 Green Party of the United States As Adopted by the Green National Committee September 2010 About the Green Party The Green Party of the United States is a federation of state Green Parties. Committed to environmentalism, non-violence, social justice and grassroots organizing, Greens are renewing democracy without the support of corporate donors. Greens provide real solutions for real problems. Whether the issue is universal health care, corporate globalization, alternative energy, election reform or decent, living wages for workers, Greens have the courage and independence necessary to take on the powerful corporate interests. The Federal Elec - tions Commission recognizes the Green Party of the United States as the official Green Party National Com - mittee. We are partners with the European Federation of Green Parties and the Federation of Green Parties of the Americas. The Green Party of the United States was formed in 2001 from of the older Association of State Green Parties (1996-2001). Our initial goal was to help existing state parties grow and to promote the formation of parties in all 51 states and colonies. Helping state parties is still our primary goal. As the Green Party National Com - mittee we will devote our attention to establishing a national Green presence in politics and policy debate while continuing to facilitate party growth and action at the state and local level. Green Party growth has been rapid since our founding and Green candidates are winning elections through - out the United States. State party membership has more than doubled. At the 2000 Presidential Nominating Convention we nominated Ralph Nader and Winona LaDuke for our Presidential ticket. -

The Case for Fraud in Ohio Election 2004

The Case for Fraud in Ohio Election 2004 I. Voter Suppression A. Overly Restrictive Registration Requirements B. Incompetence in Processing Registrations C. Challenges to New Registrants on Insufficient Grounds D. Misinformation About Voting Status/Location/Date E. Voter Intimidation F. Voting Machine Shortages/Malfunctions G. Overly Restrictive Rules & Incorrect Procedure Regarding Provisional Ballots H. Poorly Designed Absentee Ballots Caused Voters to Mark Incorrect Candidate II. Access to Voting Systems Before Election Violates Protocol III. A Third-Rate Burglary in Toledo IV. Suspect Results A. Registration Irregularities B. Exceptionally High Voter Turnout C. More Votes than Voters D. Exceptionally High Rates of Undervotes E. High Rate of Overvotes Due to Ballots Pre-Punched for Bush? F. The Kerry/Connally Discrepancy G. Discrepancy between Exit Polls & Tabulated Votes V. Restricting Citizen Observation & Access to Public Documents A. Warren County Lockdown B. Restricting Citizen Access to Election Records VI. What Went Wrong with the Recounts/Investigation of Vote Irregularities A. Chain of Custody of Voting Machines & Materials Violated B. Failure to Follow Established Procedures for Recounts C. Failure to Allow Recount Observers to Fully Examine Materials D. Secretary of State Blackwell has Failed to Answer Questions VII. Recount Reveals Significant Problems VIII. Methods of Election Fraud A. Stuffing the Ballot Box B. Touchscreen voting machines appear to have been set to “Bush” as Default C. Computers pre-programmed to ‘adjust’ vote count in Bush’s favor? D. Tampering with the Tabulators: Evidence of Hacking in Real-Time? IX. Additional Observations A. Irregular/Impossible Changes in Exit Polls over time on Election Night I. -

The Calhoun-Liberty Journal

LIBERTY COUNTY 50¢ UNOFFICIAL THE CALHOUN-LIBERTY INCLUDES NOV. 6 GENERAL TAX ELECTION RESULTS PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT Romney, Ryan (REP) .........2298 OURNAL Obama, Biden (DEM) .........0939 CLJNews.comJ WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2012 Vol. 32, No. 44 Thomas Robert Stevens, Alden Link (OBJ) ...006 Gary Johnson, James P. Gray (LBT) .............009 Virgil H. Goode, Jr., James N. Clymer (CPF) .....003 Jill Stein, Cheri Honkala (GRE) .......................002 Finch elected Liberty County Sheriff; Andre Barnett, Kenneth Cross (REF) ..............000 Stewart Alexander, Alex Mendoza (SOC) ....002 Peta Lindsay, Yari Osori (PSL) ...................000 Roseanne Barr, Cindy Sheehan (PFP) .......016 Calhoun voters put Kimbrel in office Tom Hoefling, Jonathan D. Ellis (AIP) ..........002 Ross C. Anderson, Luis J. Rodriguez (JPF) ..001 There were some close races and anx- ious moments Tuesday night as big UNITED STATES SENATOR Connie Mack (REP).......................1536 changes were made in the sheriff’s of- Bill Nelson (DEM) ........................1584 fice on both sides of the Apalachicola Bill Gaylor (NPA) ............................069 River. Nick Finch, shown at left, was vot- Chris Borgia (NPA) ........................042 ed in as the new Liberty County Sheriff REP. IN CONGRESS after beating incumbent Donnie Conyers DISTRICT 2 by 177 votes. Calhoun County voted in Steve Southerland (REP) ...........2081 retired Blountstown Police Chief Glenn Al Lawson (DEM) ..........................1185 Kimbrel, right, as the new Sheriff. He STATE ATTORNEY -

Ten Stories About Election ‘06 What You Won’T Learn from the Polls

Ten Stories About Election ‘06 What You Won’t Learn From the Polls Released November 6, 2006 Contents: Page 1) What Do Votes Have to Do With It: Democrats majorities may not win seat majorities 2 2) Monopoly Politics: How on Thursday we will predict nearly all House winners… for 2008 3 3) The Untouchables: The growing list of House members on cruise control 5 4) The Gerrymander and Money Myths: The real roots of non-competition and GOP advantage 12 5) The GOP Turnout Machine Myth: If not real in 2004, why would it be now? 17 6) The 50-State Question: Measuring Dean’s gamble in 2006… and in 2016 18 7) Downballot GOP Blues: What a Democratic wave could mean for state legislatures 20 8) Of Spoilers and Minority Rule: Where split votes could swing seats – and already have 21 9) The Democrats’ Paradox: Why a win could shake up House leaders & the presidential race 24 10) Slouching Toward Diversity: Who’s to gain when a few more white men lose? 26 Appendix: 1) Incumbency Bumps: Measuring the bonus for House Members, 1996-2004 29 2) Horserace Talk: The inside track on projecting the 2006 Congressional races 30 3) Open Seat Analysis: How Monopoly Politics measures 2006 open seats 32 FairVote 6930 Carroll Avenue, Suite 610 Takoma Park, MD 20912 www.fairvote.org (301) 270-4616 What Do Votes Have to Do With It? Democrats’ Probable National Majorities May Not Result in Control of Congress On November 7, Americans will elect all 435 Members of the U.S.