Ft Empliimiulf» Tlie Plmne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darna's Bread

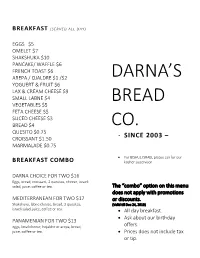

BREAKFAST (SERVED ALL DAY) EGGS $5 OMELET $7 SHAKSHUKA $10 PANCAKE/ WAFFLE $6 FRENCH TOAST $6 AREPA / OJALDRE $1 /$2 DARNA’S YOGUERT & FRUIT $6 LAX & CREAM CHEESE $9 SMALL LABNE $4 BREAD VEGETABLES $5 FETA CHEESE $5 SLICED CHEESE $3 BREAD $4 CO. QUESITO $0.75 CROISSANT $1.50 - SINCE 2003 – MARMALADE $0.75 For BISHUL ISRAEL please ask for our BREAKFAST COMBO kosher supervisor. DARNA CHOICE FOR TWO $16 Eggs, bread, croissant, 2 quesitos, cheese, israeli salad, juice, coffee or tea. The “combo” option on this menu does not apply with promotions MEDITERRANEAN FOR TWO $17 or discounts. Shakshuka, labne cheese, bread, 2 quesitos, (Valid till Dec 24, 2019) israeli salad, juice, coffee or tea. All day breakfast. Ask about our birthday PANAMENIAN FOR TWO $13 eggs, local cheese, hojaldre or arepa, bread, offers. juice, coffee or tea. Prices does not include tax or tip. STARTERS MOZARELLA STICKS $13 Breaded and fried, served with tomato soy HUMMUS $10 sauce. Served with focaccia. SOUP / CREAM $4/$7 CEVICHE $12 Classic panamenian style. FOCACCIAS TUNA TARTAR $14 Raw tuna, avocado, soy and sésamo dressing. DALIA’S FOCACCIA $14 Pesto, portobello, tomato confit, balsamic SALMON CARPACCIO $15 dressing and feta cheese. Served with romaine and capers dressing. PORTOBELLO FOCACCIA $13 NACHOS $12 Portobello and balsamic dressing. Tortilla, black beans, guacamole, tomato salsa, cheese and sourcream. MUSHROOM FOCACCIA $12 Tomato confit, white mushrooms and LABNE CHEESE $12 mozzarella cheese. With zaatar focaccia. CAPRESSE FOCACCIA $12 GREEK EGGPLANT $11 Tomato, pesto, mozzarella, Kalamata and Breaded and fried, served with saziki sauce. balsamic dressing. -

20 of the Best Food Tours Around the World

News Opinion Sport Culture Lifestyle Travel UK Europe US More Top 20s 20 of the best food tours around the world Feast your eyes on these foodie walking tours, which reveal the flavours – and culture – of cities from Lisbon to Lima, Havana to Hanoi The Guardian Wed 26 Jun 2019 14.19 BST EUROPE Porto Taste Porto’s tours are rooted in fundamental beliefs about the gastronomic scene in Portugal’s second city. First, Portuenses like to keep things simple: so, no fusion experiments. Second, it’s as much about the people behind the food, as the food itself. “Food is an expression of culture,” says US-born Carly Petracco, who founded Taste Porto in 2013 with her Porto-born husband Miguel and his childhood buddy André. “We like to show who’s doing the cooking, who’s serving the food, who’s supplying the ingredients, and so on.” She’s good to her word. Walking the city with one of the six guides feels less like venue-hopping and more like dropping in for a catch-up with a series of food-loving, old friends. Everywhere you go (whether it’s the Loja dos Pastéis de Chaves cafe with its flaky pastries or the Flor de Congregados sandwich bar with its sublime slow-roasted pork special) the experience is as convivial as it is culinary. And it’s not just food either. Taste Porto runs a Vintage Tour option that includes a final stop at boutique wine store, Touriga, where the owner David will willingly pair your palate to the perfect port. -

USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Referencerelease 28

USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard ReferenceRelease 28 Nutrients: 18:3 n-3 c,c,c (ALA) (g) Food Subset: All Foods Ordered by: Food Name Measured by: Household Report Run at: September 18, 2016 04:43 EDT 18:3 n-3 c,c,c NDB_No Description Weight(g) Measure (ALA)(g) Per Measure 20001 Amaranth grain, uncooked 193.0 1.0 cup 0.081 36000 APPLEBEE'S, 9 oz house sirloin steak 157.0 1.0 serving 0.038 36023 APPLEBEE'S, chicken tenders platter 209.0 1.0 serving 0.000 36005 APPLEBEE'S, chicken tenders, from kids' menu 35.0 1.0 piece 0.301 36019 APPLEBEE'S, chili 136.0 1.0 cup 0.049 36021 APPLEBEE'S, coleslaw 76.0 1.0 serving 0.348 36022 APPLEBEE'S, crunchy onion rings 350.0 1.0 serving 4.123 36001 APPLEBEE'S, Double Crunch Shrimp 206.0 1.0 serving 2.013 36018 APPLEBEE'S, fish, hand battered 250.0 1.0 serving 1.205 36002 APPLEBEE'S, french fries 164.0 1.0 serving 1.194 36003 APPLEBEE'S, KRAFT, Macaroni & Cheese, from kid's menu 124.0 1.0 cup 0.272 36004 APPLEBEE'S, mozzarella sticks 32.0 1.0 piece 0.162 21527 ARBY'S, roast beef sandwich, classic 149.0 1.0 sandwich 0.226 09037 Avocados, raw, all commercial varieties 150.0 1.0 cup, cubes 0.166 09038 Avocados, raw, California 230.0 1.0 cup, pureed 0.255 03189 Babyfood, cereal, oatmeal, dry fortified 3.2 1.0 tbsp 0.002 03194 Babyfood, cereal, Rice, dry, fortified 2.5 1.0 tbsp 0.001 33879 Babyfood, finger snacks, GERBER, GRADUATES, LIL CRUNCHIES - MILD CHEDDAR 8.9 0.5 cup 0.019 18001 Bagels, plain, enriched, with calcium propionate (includes onion, poppy, sesame) 99.0 1.0 bagel 0.024 18002 -

December 2020 Polenta Party!

December 2020 Polenta Party! It’s hard to let go of cherished celebrations. So, this season, make your meals with your immediate family parties to celebrate! Think out of the ordinary and pull together a rustic Polenta Party in no time. Creamy polenta, grilled sausages, caramelized onions, roasted garlic and tomatoes, good olives, and a wedge of Parmigiano Reggiano– lots of Northern Italian favorites. Creamy Polenta Ingredients 1 cup stone-ground polenta 3 Tbl extra-virgin olive oil 5 cups water, divided ½ tsp sea salt Preparation For a creamier texture, you can pulse the dry Turn off the heat and whisk in the olive oil polenta in a blender first. and sea salt. Want it even creamier? Add some cheese (Parmigiana Reggiano is In a medium stock pot, bring 3 ½ cups of classic, but creamy goat cheese or burrata water to a high simmer. Slowly whisk in the are also great choices). Cover and let stand polenta. Add 1 more cup of water and for 5 minutes. Season to taste and serve hot. simmer for 15 minutes, stirring frequently. Continue to add water while stirring until you Polenta thickens as it cools. You can reheat, have the consistency you like. The polenta adding more water and/or olive oil to make it should be creamy. smooth and creamy. Fun fact: In Northern Italy, polenta and all the wonderful accompaniments are served directly on large wooden boards that fill the table. It’s a feast for all the senses. Alliums I Love! I never met an allium I didn’t like. -

Snack Recipes, Student Workshops & Lab Manual

Fresh & Local Farm to School Snack Recipes, Student Workshops & Lab Manual Fresh & Local Farm to School These recipes were created by faculty and students of George Brown College working on the research project “Generating Success for Farm to School.” They were created to use at workshops we delivered for middle and secondary schools, the applied culinary portion of the work- shop. There was a theoretical portion, too, on food security, food literacy, food systems, and the benefits of a healthy diet. You'll find resources for the theory workshops in our report. The lab manual was courtesy of Continuing Education at George Brown College. The project received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Fresh & Local Farm to School 4 Introduction The research project 'Generating Success for Farm to For the theory workshops, students brainstormed food School' investigated the benefits of the Farm to School security, food systems, and food literacy issues. (F2S) approach and the conditions necessary to sup- They then participated in a culinary workshop, port them. It also attempted to identify best practices where a sanitation, safety, and recipe demo preceded the for stakeholders by understanding the diverse conditions students producing (usually) two recipes. and key factors that lead to measures of success for F2S activities. Download the report here. The workshops were a great success. Participants gained insight and understanding of many of the concepts The activities align with the three pillars of F2S: underpinning the three pillars of F2S. Hands-On Learning (Food Literacy); Healthy, Local Food in Schools; Acknowledgments School and Community Connectedness. -

Country Briefs 2012

Briefing Your Country ISP 2012 “Delicious” in Mandarin Chinese: 好吃 (Fei chang hao chi) or 美味 (Mei ASIA wei) (The People's Republic of) China “Thank you” in Mandarin Chinese: 谢谢(sie sie) Contributed by How to greet: Shaking hands Zhanying Cao; Liu Xiaobei; Yiwen Hu; Greeting among friends: Hello; 最近怎么样啊(how are you doing Yihao Zhou; Yang these days); Chi Le Ma? (Have you eaten?) Jihao; Muyuan; Xu Hanyue; Yezi Yang; Liu Food(s) and drink(s): food: rice, noodles, wontons, jiaozi (Chinese Jingjia; Yuzhu Xiang; dumplings), zongzi (rice dumplings), nian gao (Year Cake), tangyuan Jinqiao Lin drinks: green tea, shaojiu (white liquor), huangjiu (yellow wine) Capital: Beijing Most important holidays: The Spring Festival, Lantern Festival, Qingming Festival (Tomb Sweeping Day), Labor Day (May 1), Dragon Population: 1.3 billion Boat Festival, Mid-autumn Festival, National Day, Qixi Festival (Chinese Valentine's Day), Ghost Festival, Double Ninth Day, Spirit Festival, Main religion(s): Atheism; Taoism; Buddhism Dongzhi Festival Political leader(s): Chairman/President - Hu Jintao; Premier - Wen Jiabao Famous musician & songs: Song Zuying& Jay Chou 茉莉花(Jasmine; Little known fact: The longest dynasty of China is Zhou; only a small musicians: Liu Tianhua, Xian Xinghai, Tan Dun, Liu Sola, Lang Lang, number of Chinese could do Chinese Kung Fu; Chinese people consume Yo-Yo Ma, Cui Jian, Ye Xiaogang, Lo Ta-yu, Teresa Teng 45 billion pairs of chopsticks per year. songs: You and me, Moli Hua, The Moon represents my heart; Jay Chou “Nunchakus”, Lang Lang; Song Zuying <La Mei Zi> Language(s): Mandarin Chinese; Cantonese; Other regional dialects depending on cities Popular sport(s): Soccer, ping-pong “Hello” in Mandarin Chinese: 你好 (Ni hao) Celebrities: Confucius; Yao Ming, Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Yuan “Goodbye” in Mandarin Chinese: 再见 (Zai jian) Longping, Tsien Hsueshen, Lang Lang, Li Yundi, Yang Liwei, etc. -

Deluxe Buffet Menu

Deluxe Buffet Menu 93.32 per person (25 person minimum) BUTLERED SHRIMP & SUSHI BUTLERED HORS D’OEUVRES Please select seven: Thai Peanut Chicken Skewer with sweet chili dipping sauce* Chicken & Waffle with bacon, bourbon maple aïoli Marinated Steak, Roasted Peppers & Pepper Jack Quesadilla Jerk Chicken Nacho with pineapple salsa Escargot Spoon with garlic butter, parsley and shallots* Sweet Potato & Shrimp Cakes Peking Duck on scallion pancake* Crab Cakes with house made lemon grass aïoli Crayfish Mac & Cheese served in mini tart shell Open Faced B.L.T. Sandwich with sun dried tomato aïoli Kung Pao Cauliflower Seasonal Flatbread Pizza** Potato Skins with mixed cheese, bacon and sour cream* Bacon Wrapped Meatloaf with Jack Daniel’s sweet potato mash Fish & Chips with tartar sauce Dates in a Blanket spiced almond stuffed date wrapped in apple wood bacon* Mini Cheeseburgers served on a house made bun with onions, peppers and a spicy ketchup BBQ Pulled Pork & Cheese Popover Chorizo Sausage Puff Doggie with smoky mustard sauce Meat & Potatoes potato croquette topped with pulled short rib Assorted Filo Cups — cranberry and Brie, spinach and feta, apple 1555 Asylum Avenue and Gorgonzola West Hartford, CT 06117 with bacon jam E-mail: [email protected] Goat Cheese Bruschetta 860.231.8823 Chicken Arepa with pico de gallo and sour cream pondhousecafe.com Grilled & Chilled Scallops* 2021 Puff Doggie with grain mustard sauce Eggplant Parmesan with mozzarella, tomato and pesto Root Vegetable Fries potato and sweet potato with spicy ketchup Tempura -

Miton Catering Guide 2017-2018-2.Pptx

Catering Guide guidelines Flik Independent Schools Dining is pleased to present this Catering Menu developed for Milton Academy. The guide serves only as a sampling of our catering abilities and does not reflect the full range of selections and services we can provide. Our Director of Catering will gladly assist you in developing a customized menu for your next meeting or event. We look forward to serving your catering needs. All Catering requests must be submitted using the on-line Catering Order Form http://www.milton.edu/about/dining-at-milton/catering-form *Catering account # needed to place order *Once order is successfully submitted you will receive an email confirmation All catering orders require a minimum of five business days’ notice. Final guest count is due 3 business days prior to your event. This represents the number of guests you will be charged for. Conditions and Service Fees: Mornings before 9am and Evenings after 7pm along with Weekends may require an additional surcharge to defray the cost of overtime labor *Orders placed within 5 day of the event will incur a 5% surcharge *Orders placed within 48 hours of the event will incur 10% surcharge *Orders placed within 24 hours of the event will incur 25% surcharge All orders are charged a 10% service fee on food, linen, liquor and rental items (waived if picked up) as well as a 3% contractual fee Reserving a Location Prior to placing your catering order you must book the space on-line at http://milton.edu/news/calendar-event-request. Questions should be directed to the Calendar Manager at extension 2211. -

Please Click Here for the 2019 Show Guide

Buy your tickets online and save! theshow.co.nz/tickets IDE OFFICIAL SHOW GU WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT, CHRIS HERBERT It gives me great involved in the Cattle Section of the be entertained for hours on the Tip Top pleasure to be writing Show. My wife, Katrina, helps amongst Family Lawn with a few surprises from our this message as the the committee with the organising in the friends at Tip Top and Cookie Time. President of the months prior to the Show and my two I would like to take this opportunity to 2019 New Zealand boys are now paving their own way in the thank our committed volunteers. The Agricultural Show. exhibiting world too. Show sees over 500 individuals commit For 157 years, the The Show offers the best excuse for time and effort into making it a success Canterbury A&P families and friends, old and new, to come and I am proud to lead you all forward Association’s Show has served as a together once a year and celebrate. This to the Show this year. I also extend a fantastic opportunity for various groups year, we welcome back the old Show thank you to our valuable sponsors, your of people to come together, compete, favourites along with the new. Of course, continued support and activations at the learn and experience activities they are we will have our famous woodchopping Show help us to create the incredible unlikely to encounter anywhere else. event, the adrenaline-fueled endurocross event we have all come to love. Whether you come to compete in the and one of the largest equestrian Join us at the Show, November 13-15, at largest demonstration of livestock in New programmes in New Zealand. -

SFFG1506 Sept Newsletterv2

Issue 45, September 2019 TREND WATCH Handheld meals are convenient, sharable and fun! It's a primal instinct. Who among us doesn't like to disregard the formality of forks and knives and just dig in with our fingers once in a while? We all do! And that's because it's just plain fun. Today, handhelds are bigger than ever. Chefs love them because they're the perfect meal or snack for breakfast, lunch and dinner regardless of the venue. "According to the NRA & NPD Group, 81% of operators report increased profits when they offer handheld items."1 Eating with their hands allows food lovers to savor a true sensory experience. As consumers demand more handheld foods, restaurants continually need to find ways to change up their menus to include unique ones. In addition to the customers’ experience, handhelds allow chefs to showcase their creativity. Less training, space and equipment are needed, due to their sim- plicity, which also allow handhelds to be easily adapted for any daypart. For full service, limited service and fast-casual restaurants, to coffee shops and catering, handhelds are versatile, easy to make and ready to enjoy. Visit SmithfieldHandsOn.com for handheld recipe inspiration. Today's Hottest Trends in Handhelds APPETIZERS Appetizers are the fun and sharable small plate classic that is more often than not also a handheld meal. Some of the more popular ones that have shown growth:2 WINGS- on 44% of menus & still seeing growth PORK “WINGS”- up 25% on menus over 4 years RIBS- on 20%+ of menus Hint: Make ribs even more handheld-friendly by pulling the meat down the bone a bit and exposing a “handle.” 1 1. -

MCC Food Fun Page

MCC Food Fun Page Why grow vegetables in a greenhouse? Victoria Mamani Sirpa lives in a community in Bolivia that’s very high above sea level. It’s a difficult climate for growing vegetables, and people used to travel more than an hour to find some! That’s why MCC helped people build greenhouses specially designed for this area. The roofs are covered with yellow plastic to allow just the right amount of sunlight to shine inside for the plants to grow, and rain barrels help catch water for the plants. She said, “It makes me very happy to see the families producing and eating their own vegetables.” Veggie word scramble Unscramble the words to find some vegetables you could plant in your garden. Use the highlighted letters to reveal a hidden word. peglangt noweartlem sepppre buccumers moatoets Plan a vegetable garden Draw some vegetables you would plant in your own garden. Cheese Pastry Recipe A Bolivian snack Sift: 4 c. flour 1 t. salt 4 t. baking powder 2 T. sugar Add: 1/2 c. margarine 1 c. warm milk 4 egg yolks (reserve whites) Mix well. Divide dough in half. Pat out half in greased 13x9-inch pan. In a separate bowl, beat until foamy: 4 egg whites Add: 1/2-1 lb. Monterey Jack or similar cheese, grated Mix. Spread half of cheese mixture on dough in pan. Pat out rest of dough on cheese layer and spread remaining cheese mixture on top. Bake at 350 F about 30 minutes until golden brown. Cut into squares to serve. -

Street Food Suddenly Snacking Takes on a Completely New Dimension

copyright editions olo editions Street Food Suddenly snacking takes on a completely new dimension. Take a road trip across the word to sample some truly authentic eats. Street Food has always been a handy and affordable solution, whatever your budget. Street food visits five continents to explore different cultures of food on the move. Discover new flavors and taste combinations, and take a fresh look at some classic street dishes. SPECIFICATIONS Format 210 x 280 mm Number of pages 288 pp Approx. 37,000 words Price 30 € Rights available all except for France 104 boulevard arago | 75014 paris | france | contact nicolas marçais | +33 1 44 16 92 03 | [email protected] | copyrighteditions.com CONTENT United States Bag El With Pastrami Bag El With Salmon And Cream Cheese Thin Pie - Great Britain Chicken Wings Muffins - Great Britain Club Sandwich With Pretzels - Germany Smoked Salmon, Currywurst - Germany Cucumber Köttbu Llar - Sweden Relish And Cottag E Tunnbrodsrulle - Sweden Cheese Karto Ffelmad - Denmark Hamburger Fiskboller - Norway Hot Dog La Mb Kebab S - Russ Ia Chicken Nuggets Perogies - Russ Ia Hazelnut Browni E Tchebourekis - Russ Ia Cooki Es Khachapuri - Georgia St Rawb Erry Smoot Hie - So Uthern Europe Ca Ramel Sundae Koulouri - Greece Caribbean And So Uth Sou Vlaki - Greece America Baccalà Mantecato - Italy Co D Fritt Ers - Martinique Bruschetta - Italy Patty - Jamaica Ca Lzone - Italy Arepa S - Venezuela Stu Ffed With Cream Chicken Empana Das - Cheese And Rocket Argentina Focaccia - Italy Pork Burrito S - Mexico Mondeghili