Sanctioning Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Indy Stars Revere the Salt

Many Indy Stars Revere The Salt Astonishingly, until this year, I had awhile and get your lakester running! other car was a rear engine. racing luck with mixed results. never covered “the greatest spectacle”, End personal segue. Reaching way back, we find my all- Indy Ace Tony Bettenhausen drove aka the Indy 500. As a veteran motor- Let’s start with names that most LSR time land speed racing hero, Frank on the salt in 1955 setting 18 Internation- sports journalist, my brain would have folks know, but may not realize they had Lockhart who, at the 1926 Indianapolis al Records in the F Class (1.500 cc) exploded to just be a spectator, so I put ties to Indiana oval. Those people that 500, was a relief driver for Peter Kreis’s records in an OSCA sports car with together a little track lapping activity. have a year and speed in parentheses indi- eight cylinder supercharged Miller. He c-driver Marshall Lewis. The idea was for land speed, drag, jet cates Bonneville 200MPH Club won the race becoming the fourth rookie Among other Indy racers who also and rocket racer Paula Murphy, aka “Miss membership. ever to do so. Lockhart, you will remem- drove on the salt you’ll find such names STP” to reprise her milestone role as the For instance, cheerful and always ber, together with the Stutz Automobile as: Dan Gurney, Rex Mays, Jack McGrath, first woman ever allowed to drive a race charming Leroy Newmayer (1953 Company, broke World Land Speed Cliff Bergere, Wilbur D’Alene, Bud Rose, car upon the venerable brickyard oval. -

3:00Pm at Landmark Ford in Tualatin. Shop Tour to Aldridge Motorsports

1 February, 2018 Join us at the next club meeting, February 18, 3:00pm at Landmark Ford in Tualatin. Shop tour to Aldridge Motorsports Denny and Pam Aldridge threw out the welcome mat for SAAC NW on Feb 3rd and we had a great time. From the awesome line-up of engines on display as we walked in, the historical photos on the walls, and Ludicrous Speed Racing’s AC Cobra still on display, there was a lot to see! Denny intro- duced us to Jim and Hank Bothwell, both members of the Ludicrous team, as he talked about racing the gold Holman & Moody mustang and the Cobra in vintage racing events. Lots of questions kept Denny busy for a good portion of the time. We reluctantly had to leave for lunch, 30 minutes later than planned. Thank you Pam and Denny for hosting our group. It was a FUN event !! 2 3 Dan Gurney’s recent passing brought about a lot of great tributes. This is a quick historical review of the impact he had on auto racing. Created back in 2014. This film was shown at the Edison-Ford Medal Tribute presentation to Mr. Gurney. I enjoyed it a lot!. Catch it HERE. A quick Google search for “Dan Gurney cars” brought back a crazy long list of cars he drove “Gurney Flap” Original Gumball rally “Champagne spraying.” A Tribute to Dan Gurney and his All American Racers company. Watch an old Speed Channel video about the F1 win at Spa in 1967. ( warning 22 minutes long) Find it HERE. -

Mclaren - the CARS

McLAREN - THE CARS Copyright © 2011 Coterie Press Ltd/McLaren Group Ltd McLAREN - THE CARS INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION WILLIAM TAYLOR WILLIAM TAYLOR Bruce Leslie McLaren’s earliest competitive driving While he was learning how to compete at this level, the experiences came at the wheel of a highly modified 1929 Ulster period was of crucial importance to Bruce when it Austin Ulster, an open-topped version of Britain’s cheap came to gaining an understanding of the mechanical side and ubiquitous Austin Seven. Spurred on by his father, of the sport. As a result, by the early 1950s he was already Les, a skilled engineer and a keen motorsports a highly capable and ingenious mechanic, something he enthusiast, Bruce’s initiation into the relatively small ably demonstrated when the Ulster’s cylinder head community of New Zealand and Australian racing drivers eventually cracked. Rescuing a suitable replacement from took place at a hillclimb at Muriwai Beach in 1952. It a humble 1936 Austin Ruby saloon, he filled the combustion was about 25 miles from the McLaren family home in chambers with bronze which he then expertly ground to the Auckland, and happened to be part of their holiday appropriate shape using a rotary file. Once the engine was home. He had just turned 15. reassembled the Ulster proved good for 87mph, a 20 per cent improvement on its official quoted maximum of 72mph. The Ulster had already been in the family for almost three years, having been acquired by Les, in many pieces, for Thereafter such detail improvements came one after another. -

1911: All 40 Starters

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ROOKIES BY YEAR 1911: All 40 starters 1912: (8) Bert Dingley, Joe Horan, Johnny Jenkins, Billy Liesaw, Joe Matson, Len Ormsby, Eddie Rickenbacker, Len Zengel 1913: (10) George Clark, Robert Evans, Jules Goux, Albert Guyot, Willie Haupt, Don Herr, Joe Nikrent, Theodore Pilette, Vincenzo Trucco, Paul Zuccarelli 1914: (15) George Boillot, S.F. Brock, Billy Carlson, Billy Chandler, Jean Chassagne, Josef Christiaens, Earl Cooper, Arthur Duray, Ernst Friedrich, Ray Gilhooly, Charles Keene, Art Klein, George Mason, Barney Oldfield, Rene Thomas 1915: (13) Tom Alley, George Babcock, Louis Chevrolet, Joe Cooper, C.C. Cox, John DePalma, George Hill, Johnny Mais, Eddie O’Donnell, Tom Orr, Jean Porporato, Dario Resta, Noel Van Raalte 1916: (8) Wilbur D’Alene, Jules DeVigne, Aldo Franchi, Ora Haibe, Pete Henderson, Art Johnson, Dave Lewis, Tom Rooney 1919: (19) Paul Bablot, Andre Boillot, Joe Boyer, W.W. Brown, Gaston Chevrolet, Cliff Durant, Denny Hickey, Kurt Hitke, Ray Howard, Charles Kirkpatrick, Louis LeCocq, J.J. McCoy, Tommy Milton, Roscoe Sarles, Elmer Shannon, Arthur Thurman, Omar Toft, Ira Vail, Louis Wagner 1920: (4) John Boling, Bennett Hill, Jimmy Murphy, Joe Thomas 1921: (6) Riley Brett, Jules Ellingboe, Louis Fontaine, Percy Ford, Eddie Miller, C.W. Van Ranst 1922: (11) E.G. “Cannonball” Baker, L.L. Corum, Jack Curtner, Peter DePaolo, Leon Duray, Frank Elliott, I.P Fetterman, Harry Hartz, Douglas Hawkes, Glenn Howard, Jerry Wonderlich 1923: (10) Martin de Alzaga, Prince de Cystria, Pierre de Viscaya, Harlan Fengler, Christian Lautenschlager, Wade Morton, Raoul Riganti, Max Sailer, Christian Werner, Count Louis Zborowski 1924: (7) Ernie Ansterburg, Fred Comer, Fred Harder, Bill Hunt, Bob McDonogh, Alfred E. -

Rear View Mirror

RReeaarr VViieeww MMiirrrroorr February and March 2010 / Volume 7 No. 6 Pity the poor Historian! – Denis Jenkinson // Research is endlessly seductive, writing is hard work. – Barbara Tuchman Automobile Racing History and History Clio Has a Corollary, Casey, and Case History: Part II Clio Has a Corollary The Jackets Corollary: It is practically impossible to kill a myth once it has become widespread and reprinted in other books all over the world. 1 L.A. Jackets The Jackets Corollary is really a blinding flash of the obvious. Although it is derived from a case that related to military history, a discipline within history which suffers many of the problems that afflict automobile racing history, it seems to state one of the more serious problems with which historians must wrestle in automobile racing history. Once errors get disseminated into a variety of sources, primarily books, there is a tendency for these errors to take on a life of their own and continue to pop up years after they have been challenged and corrected. Casey (and Case History) at the Battlements The major basic – if not fundamental – difference between the card-carrying historians and the others involved in automobile racing history – the storytellers, the Enthusiasts, the journalists, the writers, as well as whomever else you might wish to name – comes down to this one thing: references. Simply stated, it is the tools of the historian’s trade, footnotes, bibliographies, citing sources used, all of which allow others to follow the same trail as the historian, even if that results in dif- ferent interpretations of the material, that separates the card-carrying historian from his brethren and sisters who may enjoy reading history – or what may appear to be history, but not the sau- sage-making aspects of the historian’s craft. -

(212) 867-1490 Steed Industries, Inc

From: Brad Niemcek, Inc. 51 East 42nd Street New York, N.Y. 10017 (212) 867-1490 For: STEED INDUSTRIES, INC. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Itasca, Illinois 60143 4/23/73 CARL A. HAAS Carl A. Haas belongs to a rather exclusive club. Its members are those entrepreneurs in motor racing who can claim to actually making a living at doing something they love. Many aspire to "business" careers in motor racing. Still more love what they are doing. But relatively few make a living at it. Carl Haas is a leader among them. Haas is a 20-year veteran of successful race team management -- a businessman who knows what it takes to "win" in a most demanding business specialty and who does it year after year . at a profit, A German by birth, Carl Haas was an auto enthusiast at an early age. He began racing himself, as an amateur, in 1953. His cars visited race circuits from Nassau to California, and he did well. In 1966 he hung up his goggles and turned full attention to the race car importing business he had founded two years earlier as a part-time enterprise that quickly became a full-time occupation. His business acumen was evident early, in his choices of the right equipment to bring into North America for a growing competitor market, and in the proper method of making that equipment available to his customers. -more- CARL A. HAAS / — 2 He decided in 1961, for instance, that a new competition gearbox developed by a friend, Michael Hewland of England, would have wide application in the competition market here. -

RVM Vol 7, No 2

RReeaarr VViieeww MMiirrrroorr October 2009 / Volume 7 No. 2 “Pity the poor Historian!” – Denis Jenkinson H. Donald Capps Connecting the Dots Or, Mammas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Historians.... The Curious Case of the 1946 Season: An Inconvenient Championship It is practically impossible to kill a myth of this kind once it has become widespread and perhaps reprinted in other books all over the world. L.A. Jackets 1 Inspector Gregory: “Is there any point to which you wish to draw my attention?” Sherlock Holmes: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.” Inspector Gregory: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” Sherlock Holmes: “That was the curious incident.” 2 The 1946 season of the American Automobile Association’s National Championship is something of “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma” as Winston Churchill remarked about Russia in 1939. What follows are some thoughts regarding that curious, inconvenient season and its fate in the hands of the revisionists. The curious incident regarding the 1946 season is that the national championship season as it was actually conducted that year seems to have vanished and has been replaced with something that is something of exercise in both semantics and rationalization. In 1946, the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (AAA or Three-A) sanctioned six events which were run to the Contest Rules for national championship events: a minimum race distance of one hundred miles using a track at least one mile in length and for a specified minimum purse, a new requirement beginning with the 1946 season. -

We Celebrate One of the Great Racing Car Constructors

LOLA AT 60 WE CELEBRATE ONE OF THE GREAT RACING CAR CONSTRUCTORS Including FROM BROADLEY TO BIRRANE GREATEST CARS LOLA’S SECRET WEAPON THE AUDI CHALLENGER The success of the Mk1 sports-racer, usually powered by the Coventry Climax 1100cc FWA engine, brought Lola Cars into existence. It overshadowed the similar e orts of Lotus boss Colin Chapman and remained competitive for several seasons. We believe it is one of designer Eric Broadleyʼs greatest cars, so turn to page 16 to see what our resident racer made of the original prototype at Donington Park. Although the coupe is arguably more iconic, the open version of the T70 was more successful. Developed in 1965, the Group 7 machine could take a number of di erent V8 engines and was ideal for the inaugural Can-Am contest in ʼ66. Champion John Surtees, Dan Gurney and Mark Donohue won races during the campaign, while Surtees was the only non-McLaren winner in ʼ67. The big Lola remains a force in historic racing. JEP/PETCH COVER IMAGES: JEP/PETCH IMAGES: COVER J BLOXHAM/LAT Contents 4 The story of Lola How Eric Broadley and Martin Birrane Celebrating a led one of racing’s greatest constructors 10 The 10 greatest Lolas racing legend Mk1? T70? B98/10? Which do you think is best? We select our favourites and Lola is one of the great names of motorsport. Eric Broadley’s track test the top three at Donington Park fi rm became one of the leading providers of customer racing cars and scored success in a diverse range of categories. -

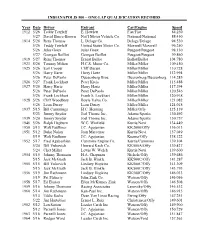

One Lap Record

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ONE-LAP QUALIFICATION RECORDS Year Date Driver Entrant Car/Engine Speed 1912 5/26 Teddy Tetzlaff E. Hewlett Fiat/Fiat 84.250 5/27 David Bruce-Brown Nat’l Motor Vehicle Co. National/National 88.450 1914 5/26 Rene Thomas L. Delage Co. Delage/Delage 94.530 5/26 Teddy Tetzlaff United States Motor Co. Maxwell/Maxwell 96.250 5/26 Jules Goux Jules Goux Peugeot/Peugeot 98.130 5/27 Georges Boillot Georges Boillot Peugeot/Peugeot 99.860 1919 5/27 Rene Thomas Ernest Ballot Ballot/Ballot 104.780 1923 5/26 Tommy Milton H.C.S. Motor Co. Miller/Miller 109.450 1925 5/26 Earl Cooper Cliff Durant Miller/Miller 110.728 5/26 Harry Hartz Harry Hartz Miller/Miller 112.994 5/26 Peter DePaolo Duesenberg Bros. Duesenberg/Duesenberg 114.285 1926 5/27 Frank Lockhart Peter Kreis Miller/Miller 115.488 1927 5/26 Harry Hartz Harry Hartz Miller/Miller 117.294 5/26 Peter DePaolo Peter DePaolo Miller/Miller 120.546 5/26 Frank Lockhart Frank S. Lockhart Miller/Miller 120.918 1928 5/26 Cliff Woodbury Boyle Valve Co. Miller/Miller 121.082 5/26 Leon Duray Leon Duray Miller/Miller 124.018 1937 5/15 Bill Cummings H.C. Henning Miller/Offy 125.139 5/23 Jimmy Snyder Joel Thorne Inc. Adams/Sparks 130.492 1939 5/20 Jimmy Snyder Joel Thorne Inc. Adams/Sparks 130.757 1946 5/26 Ralph Hepburn W.C. Winfield Kurtis/Novi 134.449 1950 5/13 Walt Faulkner J.C. Agajanian KK2000/Offy 136.013 1951 5/12 Duke Nalon Jean Marcenac Kurtis/Novi 137.049 5/19 Walt Faulkner J.C. -

Fernandez Media Guide 06

Team Information At-A-Glance MEDIA CONTACT: DREW BROWN Team Lowe’s Racing 1435 W. Morehead St, Ste 190 Charlotte, NC 28208 Tel: 704.714.4305 Cell: 704.650.0428 Email: [email protected] TAMY VALKOSKY Fernández Racing 17 El Prisma Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688 Tel: 949.459.9172 Cell: 949.842.3946 Email: [email protected] MEDIA RESOURCES: Additional information on Lowe’s Fernández Racing and the Rolex Series can be found at: media.lowesracing.com www.fernandezracing.net www.grandamerican.com GRAND AMERICAN ROAD RACING ASSOCIATION Adam Saal, Director of Communications Tel: 386.947.6681 Email: [email protected] MEDIA REFERENCE: OFFICIAL TEAM NAME: Lowe’s Fernández Racing FOUNDED: December 2005 OWNERS: Fernández Racing (Adrián Fernández, Tom Anderson) HEADQUARTERS: 6835 Guion Road Indianapolis IN 46268 317.299.5100 317.280.3051 Fax DRIVERS: Adrián Fernández and Mario Haberfeld ENTRY: No. 12 Lowe’s Fernández Racing Pontiac Riley KEY PERSONNEL: Tom Anderson, Managing Director Steve Miller, Team Manager Mike Sales, Chief Mechanic John Ward, Race Engineer Lowe’s Fernández Racing to Compete for 2006 Rolex Series Championship LOWE’S AND FERNÁNDEZ RACING ANNOUNCED the creation of of Key Biscayne, Fla., is a former British Formula 3 champion, who made Lowe’s Fernández Racing on January 4 of this year. The team will field the his US racing debut in the Champ Car World Series contesting the 2003 No. 12 Lowe’s Fernandez Racing Pontiac Riley Daytona Prototype for and 2004 seasons. drivers Adrián Fernández and Mario Haberfeld in the 14-race Grand “This is an honor for me to join Adrián Fernández, who I have admired American Rolex Sports Car Series. -

Orange Times Issue 2

The Orange Times Bruce McLaren Trust June / July 2014, Issue #2 Farewell Sir Jack 1926 - 2014 Along with the motorsport fraternity worldwide I was extremely saddened to th hear of Sir Jack’s recent passing on the 19 May. The McLaren family and Jack have shared a wonderful life-long friendship, starting with watching his early racing days in New Zealand, then Pop McLaren purchasing the Bobtail Cooper from Jack after the NZ summer racing season of 1957. For the following season of 1958, Jack made the McLaren Service Station in Remuera his base and brought the second Cooper with him from the UK for Bruce to drive in the NZIGP which culminated in Bruce being awarded the Celebrating 50 Years of “Driver to Europe”. Jack became his mentor and close friend and by 1959 McLaren Racing Bruce joined him as teammate for the Cooper Racing Team. The rest, as we say, is history but the friendship lived on and the BM Trust Following on from their Tasman Series was delighted to host Jack in New Zealand for a week of motorsport memories success, the fledgling BMMR Team set about in 2003 with Jack requesting that the priority of the trip was to be a visit to their very first sports car race with the Zerex see his “NZ Mum” Ruth McLaren, who, by then, was a sprightly 97 years old. th Special – on April 11 1964 at Oulton Park and I shared a very special hour with the two of them together and the love and this was a DNF/oil pressure. -

Racing, Region, and the Environment: a History of American Motorsports

RACING, REGION, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: A HISTORY OF AMERICAN MOTORSPORTS By DANIEL J. SIMONE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Daniel J. Simone 2 To Michael and Tessa 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A driver fails without the support of a solid team, and I thank my friends, who supported me lap-after-lap. I learned a great deal from my advisor Jack Davis, who when he was not providing helpful feedback on my work, was always willing to toss the baseball around in the park. I must also thank committee members Sean Adams, Betty Smocovitis, Stephen Perz, Paul Ortiz, and Richard Crepeau as well as University of Florida faculty members Michael Bowen, Juliana Barr, Stephen Noll, Joseph Spillane, and Bill Link. I respect them very much and enjoyed working with them during my time in Gainesville. I also owe many thanks to Dr. Julian Pleasants, Director Emeritus of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, and I could not have finished my project without the encouragement provided by Roberta Peacock. I also thank the staff of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. Finally, I will always be grateful for the support of David Danbom, Claire Strom, Jim Norris, Mark Harvey, and Larry Peterson, my former mentors at North Dakota State University. A call must go out to Tom Schmeh at the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame, Suzanne Wise at the Appalachian State University Stock Car Collection, Mark Steigerwald and Bill Green at the International Motor Racing Resource Center in Watkins Glen, New York, and Joanna Schroeder at the (former) Ethanol Promotion and Information Council (EPIC).