Comparative Analysis of Ecological and Cultural Protection Schemes Within a Transboundary Complex: the Crown of the Continent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park System Plan

National Park System Plan 39 38 10 9 37 36 26 8 11 15 16 6 7 25 17 24 28 23 5 21 1 12 3 22 35 34 29 c 27 30 32 4 18 20 2 13 14 19 c 33 31 19 a 19 b 29 b 29 a Introduction to Status of Planning for National Park System Plan Natural Regions Canadian HeritagePatrimoine canadien Parks Canada Parcs Canada Canada Introduction To protect for all time representa- The federal government is committed to tive natural areas of Canadian sig- implement the concept of sustainable de- nificance in a system of national parks, velopment. This concept holds that human to encourage public understanding, economic development must be compatible appreciation and enjoyment of this with the long-term maintenance of natural natural heritage so as to leave it ecosystems and life support processes. A unimpaired for future generations. strategy to implement sustainable develop- ment requires not only the careful manage- Parks Canada Objective ment of those lands, waters and resources for National Parks that are exploited to support our economy, but also the protection and presentation of our most important natural and cultural ar- eas. Protected areas contribute directly to the conservation of biological diversity and, therefore, to Canada's national strategy for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. Our system of national parks and national historic sites is one of the nation's - indeed the world's - greatest treasures. It also rep- resents a key resource for the tourism in- dustry in Canada, attracting both domestic and foreign visitors. -

Inaturalist How-To Guide

Official charitable partner of BC Parks Your Step-by-Step Guide to Becoming a BC Parks Citizen Scientist bcparksfoundation.ca/inaturalist 1 #iNatBCParks Calling All Citizen Scientists The BC Parks iNaturalist Project is bringing together citizen scientists – British Columbians, visitors and anyone who enjoys B.C.’s provincial parks and protected areas – to document biodiversity in B.C.’s parks using iNaturalist. By using this powerful, trusted mobile app and website to document observations of plants, animals and other organisms, British Columbians and park visitors can contribute to the understanding of life found in B.C.’s parks and protected areas. The BC Parks iNaturalist Project is a collaboration between: What is ? iNaturalist is a mobile phone app and website used around the world to crowdsource observations of plants, animals and other organisms. Users upload photos of observations and iNaturalist’s image recognition software suggests the identity of the organism. A community of keen citizen scientists called “identifiers” then confirm the 2 identity of documented species, helping correct any errors and verify observations to make them research grade. Why is citizen science important? Your observations through the BC Parks iNaturalist Project create an interactive record of your own explorations in B.C.’s parks and protected areas, while helping improve the understanding of the species that live in or travel through our province. You may come across rare species, species at risk and species that aren’t well-studied. Your observations may help track population and distribution changes over time as a result of factors such as climate change. It’s free. -

CANADIAN PARKS and PROTECTED AREAS: Helping Canada Weather Climate Change

CANADIAN PARKS AND PROTECTED AREAS: Helping Canada weather climate change Report of the Canadian Parks Council Climate Change Working Group Report prepared by The Canadian Parks Council Climate Change Working Group for the Canadian Parks Council Citation: Canadian Parks Council Climate Change Working Group. 2013. Canadian Parks and Protected Areas: Helping Canada Weather Climate Change. Parks Canada Agency on behalf of the Canadian Parks Council. 52 pp. CPC Climate Change Working Group members Karen Keenleyside (Chair), Parks Canada Linda Burr (Consultant), Working Group Coordinator Tory Stevens and Eva Riccius, BC Parks Cameron Eckert, Yukon Parks Jessica Elliott, Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Melanie Percy and Peter Weclaw, Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation Rob Wright, Saskatchewan Tourism and Parks Karen Hartley, Ontario Parks Alain Hébert and Patrick Graillon, Société des établissements de plein air du Québec Rob Cameron, Nova Scotia Environment, Protected Areas Doug Oliver, Nova Scotia Natural Resources Jeri Graham and Tina Leonard, Newfoundland and Labrador Parks and Natural Areas Christopher Lemieux, Canadian Council on Ecological Areas Mary Rothfels, Fisheries and Oceans Canada Olaf Jensen and Jean-François Gobeil, Environment Canada Acknowledgements The CPC Climate Change Working Group would like to thank the following people for their help and advice in preparing this report: John Good (CPC Executive Director); Sheldon Kowalchuk, Albert Van Dijk, Hélène Robichaud, Diane Wilson, Virginia Sheehan, Erika Laanela, Doug Yurick, Francine Mercier, Marlow Pellat, Catherine Dumouchel, Donald McLennan, John Wilmshurst, Cynthia Ball, Marie-Josée Laberge, Julie Lefebvre, Jeff Pender, Stephen Woodley, Mikailou Sy (Parks Canada); Paul Gray (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources); Art Lynds (Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources). -

Fundy National Park 2011 Management Plan

Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan NOVEMBER 2011 Fundy National Park of Canada Management Plan ii © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2011. Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. National Library of Canada cataloguing in publication data: Parks Canada Fundy National Park of Canada management plan [electronic resource]. Electronic monograph in PDF format. Issued also in French under the title: Parc national du Canada Fundy, plan directeur. Issued also in printed form. ISBN 978-1-100-13552-6 Cat. no.: R64-105/80-2010E-PDF 1. Fundy National Park (N.B.)—Management. 2. National parks and reserves—New Brunswick—Management. 3. National parks and reserves—Canada—Management. I. Title. FC2464 F85 P37 2010 971.5’31 C2009-980240-6 For more information about the management plan or about Fundy National Park of Canada: Fundy National Park of Canada P.O. Box 1001, Fundy National Park, Alma, New Brunswick Canada E4H 1B4 tel: 506-887-6000, fax: 506-887-6008 e-mail: [email protected] www.parkscanada.gc.ca/fundy Front Cover top images: Chris Reardon, 2009 bottom image: Chris Reardon, 2009 Fundy National Park of Canada iii Management Plan Foreword Canada’s national historic sites, national parks and national marine conservation areas are part of a century-strong Parks Canada network which provides Canadians and visitors from around the world with unique opportunities to experience and embrace our wonderful country. From our smallest national park to our most visited national historic site to our largest national marine conservation area, each of Canada’s treasured places offers many opportunities to enjoy Canada’s historic and natural heritage. -

Order of the Executive Director May 14, 2020

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Park Act Order of the Executive Director TO: Public Notice DATE: May 14, 2020 WHEREAS: A. This Order applies to all Crown land established or continued as a park, conservancy, recreation area, or ecological reserve under the Park Act, the Protected Areas of British Columbia Act or protected areas established under provisions of the Environment and Land Use Act. B. This Order is made in the public interest in response to the COVID-19 pandemic for the purposes of the protection of human health and safety. C. This Order is in regard to all public access, facilities or uses that exist in any of the lands mentioned in Section A above, and includes but is not limited to: campgrounds, day-use areas, trails, playgrounds, shelters, visitor centers, cabins, chalets, lodges, resort areas, group campsites, and all other facilities or lands owned or operated by or on behalf of BC Parks. D. This Order is in replacement of the Order of the Executive Director dated April 8, 2020 and is subject to further amendment, revocation or repeal as necessary to respond to changing circumstances around the COVID-19 pandemic. Exemptions that were issued in relation to the previous Order, and were still in effect, are carried forward and applied to this Order in the same manner and effect. Province of British Columbia Park Act Order of the Executive Director 1 E. The protection of park visitor health, the health of all BC Parks staff, Park Operators, contractors and permittees is the primary consideration in the making of this Order. -

Tourist Attractions and Museums in Belgium

GB 2009 GuideTourist Attractions and Museums in Belgium www.tourist-attractions.be www.daguitstappen.be Printed on 100% recycled paper The 18Th ediTion of The Guide To TourisT ATTrAcTions & MuseuMs in BelGiuM, The BesT Tool you cAn hAve for discoverinG BelGiuM ! Some information for your stay in Belgium... Thematic logos The Post offices are generally open from 8.30 to 17.00. Gardens, parks & nature reserves Tourist trains The banks are open from Monday to Friday from 9.00 to 16.00 Zoos & safariparks Archaeology The shops are open from 9.00 to 17.00 except on Sunday; some close between 12.00 and 14.00 Castles & fortresses Industrial Heritage Emergency number – The emergency and assistance services (police – fire department) are available at Caves & subterranean attractions Art & Crafts-Folklore the number 112, set on portable phones and only serves to call the emergency services. All medical call services are mentioned in the newspapers and in the pharmacies. Historic buildings & monuments Arts & History We remind you of the fact that the Belgian motorways are free of charge! The speed is limited to: Amusement parks Culture & Architecture - 120 km/h on motorways Recreation & Aquatic centres Military History - 90 km/h on 4 lane roads Water attractions Science & Nature - 50 km/h in the built-up area (and thus in Brussels) You should pay particular attention to the rule of giving way to traffic coming from the right. School and public holidays in Belgium Wearing a seatbelt is obligatory in the front and in the back of the car. In case of car trouble: Touring Secours: 070/34.47.77 (only from Belgium). -

Sandbanks Draft Veg Mgmt Plan

Sandbanks Vegetation Management Plan ISBN: 978-1-4435-1452-1 (PDF) MNR: 52584 (PDF) © 2009, Queen’s Printer for Ontario Printed in Ontario, Canada Cover photo: Sandbanks Provincial Park Additional copies of this publication are obtainable from: Sandbanks Provincial Park R.R. #1 Picton, ON K0K 2T0 TEL: 613-393-3319 FAX: 613-393-3404 EMAIL: [email protected] Recommended Citation: OMNR. 2009. Sandbanks Vegetation Management Plan. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. 28 pp. + Appendices. i ii Summary of Key Management Recommendations All park staff involved with operations potentially affecting Sandbanks’ vegetation communities will be required to be familiar with this plan’s intent and specific directives. Operations and Maintenance Policies (Section 3.1) • Herbicide use is restricted and must be in compliance with provincial regulations (p. 12) • Herbicide use must be kept to a minimum, using suggested chemicals and avoiding areas where park visitors and staff may contact it (p. 12) • Unless it is unsafe to do so, windthrown and dead standing trees should be left in place as they serve important ecological functions. Refer to Appendix A for a decision guide (p. 13) • When woody material must be removed from the site, it will be used to create brush piles for restoration, chipped for trail maintenance, or salvaged for firewood (p. 13) • Native insect pest outbreaks and diseases are natural processes and should not be controlled unless significant values within or adjacent to the park are threatened or the pest is a recent invader to Ontario. Forest Health Unit and zone office staff must be consulted. (p. -

Management Plan for the Threaded Vertigo (Nearctula Sp.) in Canada

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series Adopted under Section 69 of SARA Management Plan for the Threaded Vertigo (Nearctula sp.) in Canada Threaded Vertigo 2017 Recommended citation: Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2017. Management Plan for the Threaded Vertigo (Nearctula sp.) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. 2 parts, 4 pp. + 42 pp. For copies of the management plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: © Andy Teucher, British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC Également disponible en français sous le titre « Plan de gestion du vertigo à crêtes fines (Nearctula sp.) au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2017. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 http://sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=24F7211B-1 MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE THREADED VERTIGO (NEARCTULA SP.) IN CANADA 2017 Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada. In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of British Columbia has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the Management Plan for the Threaded Vertigo (Nearctula sp.) in British Columbia (Part 2) under Section 69 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). -

SOME >>NOTABLE THINGS

1928 First Community Museum: Langley (Native SOME Sons & Daughters) >>NOTABLE 1931 First Art Gallery: Vancouver Art Gallery 1932 First Pioneer Museum: Old Hastings Mill THINGS Store (Native Daughters of British Columbia) also called “Museum of B.C. Historical Relics in Memory An Early History of the Pioneers” of the BCMA 1935 First Interior BC Museum: Ashcroft Mu- seum 1937 First Museum and Archives: Kamloops Mu- seum and Archives Lesley Moore 1940 First Official Park of Totem Poles:Thun - Today, from Atlin to Zeballos, and from Archives to Zoos, derbird Park, Victoria the British Columbia Museums Association represents a membership of over 450. In recognition of its first 60 1944 First and only Boy Scouts Museum : Boy years, here are some notable things from the early years. Scouts Museum did not receive a formal name. The There are undoubtedly some errors and omissions for Museum was a “shack” located at the Waterfront which the author asks forgiveness. Park, Kelowna Between 1886 and 1955, the first twenty museums of 1947 First University Museum: UBC Museum of their kind came into being: Anthropology 1886In 1955, First Deputy Provincial Provincial Museum: Secretary The Provincial L. Wallace Museum, and In 1948 First Indigenous Museum: Skeena Treasure located in a room in the “Birdcages” of the Provincial House, Hazelton (later K’san) Legislature 1951 First Gallery on Vancouver Island: Art Gal- 1894 First City Museum:Art, Historical and Scientific lery of Greater Victoria Association, Vancouver 1951 First Museum in the Okanagan: Kelowna -

Managing Visitors in Wilderness Environments Parks Canada's

Managing Visitors in Wilderness Environments Parks Canada’s Western Workshop Surrey, British Columbia B.C. Forestry Association Green Timbers Conference Centre March 17-22,1996 Summary Proceedings Workshop Sponsors Parks Canada Pacific Yukon Region Natural Resources Branch, Ottawa Centre for Tourism Policy and Research School of Resource and Environmental Management Simon Fraser University Editors Alison Davis Siobhan Jackson Pamela Wright, Ph.D. Centre for Tourism Policy and Research School of Resource and Environmental Management Simon Fraser University Managing Visitors in Wilderness Environments, Parks Canada’s Western Workshop Parks Canada, Centre for Tourism Policy and Resear 8380-6/2 Vol. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements.. .l Setting the Stage . .2 Tom Elliot and Pam Wright THE WILDERNESS PARADOX: PERSPECTIVES ON MANAGING WILDERNESS Taking the Ecosystem Perspective. 3 Ken Lertzman, SFU Cultural Resource Management and the Concept of Wilderness . .6 Sandra Zacharias, Deva Heritage Consulting Ltd. APPLYING SCIENCE TO MANAGING WILDERNESS AND THE WILDERNESS EXPERIENCE The Monitoring Context.. .8 Dave Cole, Aldo Leopold Institute Determining Indicators of the Wilderness Experience. .12 Alan Watson, Aldo Leopold Institute Managing Visitor Impacts in the Backcountry.. 14 Dave Cole, Aldo Leopold Institute Monitoring Levels of Use in the Backcountry.. 16 Paul Lauzon, formerly with Calgary Regional Office, Parks Canada PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER: VISITOR MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES AND DECISION MAKING Merging Ecological and Social Science Data: The Jasper River Use Study.. .18 Pam Wright, SFU West Coast Trail User and Willingness to Pay Research . .22 Rick Rollins, Malaspina University College . A Cumulative Effects Assessment (CEA) of Proposed Projects in Kluane National Park Reserve, Yukon Territory . .24 George Hegmann, Axys Environmental Consulting. -

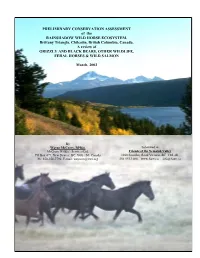

PRELIMINARY CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT of the RAINSHADOW WILD HORSE ECOSYSTEM, Brittany Triangle, Chilcotin, British Columbia, Canada

PRELIMINARY CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT of the RAINSHADOW WILD HORSE ECOSYSTEM, Brittany Triangle, Chilcotin, British Columbia, Canada. A review of GRIZZLY AND BLACK BEARS, OTHER WILDLIFE, FERAL HORSES & WILD SALMON March, 2002 By Wayne McCrory, RPBio. Submitted to McCrory Wildlife Services Ltd. Friends of the Nemaiah Valley PO Box 479, New Denver, BC, V0G 1S0, Canada 1010 Foul Bay Road Victoria, BC V8S 4J1 Ph: 250-358-7796; E-mail: [email protected] 250 592-1088 www.fonv.ca [email protected] i With thanks to the Xeni Gwet’in First Nation for welcoming us on to their traditional territory to carry out this research Xeni Gwet’in Chief Roger William on trail in Brittany Triangle in September, 2001 Suggested Citation: McCrory, W.P. 2002. Preliminary conservation assessment of the Rainshadow Wild Horse Ecosystem, Brittany Triangle, Chilcotin, British Columbia, Canada. A review of grizzly and black bears, other wildlife, wild horses, and wild salmon. Report for Friends of Nemaiah Valley (FONV), 1010 Foul Bay Road, Victoria, B.C. V8S 4J1. [Copies available from FONV at cost. For more information see: http://www.fonv.ca. Copying and distribution of this report are encouraged. Readers are welcome to cite this report but are requested that citations and references be acknowledged and placed in context]. ii One of two wild horse herds studied in Nuntsi Provincial Park in 2001. Hundreds of these small and large meadows are scattered throughout the pine forests of the Brittany Triangle, providing important habitats for wild horses, grizzly and black bears, and other wildlife from spring to fall. Over the long Chilcotin winter, the horses survive on grasses and sedges in these meadow areas as well as pine grass in the adjacent forests. -

Blue-Grey Taildropper (Prophysaon Coeruleum) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Adopted under Section 44 of SARA Recovery Strategy for the Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum) in Canada Blue-grey Taildropper 2018 Recommended citation: Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2018. Recovery Strategy for the Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. 2 parts, 20 pp. + 36 pp. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: © Kristiina Ovaska (with permission) Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de la limace-prophyse bleu-gris (Prophysaon coeruleum) au Canada » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2018. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-660-24535-5 Catalogue no. En3-4/285-2018E-PDF Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 http://sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=24F7211B-1 RECOVERY STRATEGY FOR THE BLUE-GREY TAILDROPPER (Prophysaon coeruleum) IN CANADA 2018 Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada. In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of British Columbia has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the Recovery Plan for Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum) in British Columbia (Part 2) under Section 44 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA).