Management Plan for the Threaded Vertigo (Nearctula Sp.) in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Analysis of Ecological and Cultural Protection Schemes Within a Transboundary Complex: the Crown of the Continent

Comparative Analysis of Ecological and Cultural Protection Schemes within a Transboundary Complex: The Crown of the Continent A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Community Planning In the School of Planning of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning by Keysha Fontaine B.S. University of Alaska Fairbanks, 2013 Committee Chair: Craig M. Vogel, MID Committee Advisor: Danilo Palazzo, Ph.D, M.Arch ABSTRACT Protected areas are critical elements in restoring historical wildlife migration routes, as well as, maintaining historical cultural practices and traditions. The designations created for protected areas represent a cultural and/or natural aspect of the land. However, designations for the protection of these resources fail to include measures to take into account the ecological processes needed to sustain them. Ecological processes are vital elements in sustaining cultural resources, because most cultural resources are the derivatives of the interactions with natural resources. In order to sustain natural resources, especially wildlife, the processes of fluctuating habitat change and migration are pivotal in maintaining genetic diversity to maintain healthy populations with the fittest surviving. The survival of the fittest species allow populations to have greater adaptability in the face of climate change. Currently in the Crown of the Continent (COC), several non-profit organizations are collaborating under an umbrella initiative, the Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative, to restore historical migration routes. The collaborators of this initiative performed ecological planning of the entire Yellowstone to Yukon region to identify impediments that may hinder wildlife movements. -

Inaturalist How-To Guide

Official charitable partner of BC Parks Your Step-by-Step Guide to Becoming a BC Parks Citizen Scientist bcparksfoundation.ca/inaturalist 1 #iNatBCParks Calling All Citizen Scientists The BC Parks iNaturalist Project is bringing together citizen scientists – British Columbians, visitors and anyone who enjoys B.C.’s provincial parks and protected areas – to document biodiversity in B.C.’s parks using iNaturalist. By using this powerful, trusted mobile app and website to document observations of plants, animals and other organisms, British Columbians and park visitors can contribute to the understanding of life found in B.C.’s parks and protected areas. The BC Parks iNaturalist Project is a collaboration between: What is ? iNaturalist is a mobile phone app and website used around the world to crowdsource observations of plants, animals and other organisms. Users upload photos of observations and iNaturalist’s image recognition software suggests the identity of the organism. A community of keen citizen scientists called “identifiers” then confirm the 2 identity of documented species, helping correct any errors and verify observations to make them research grade. Why is citizen science important? Your observations through the BC Parks iNaturalist Project create an interactive record of your own explorations in B.C.’s parks and protected areas, while helping improve the understanding of the species that live in or travel through our province. You may come across rare species, species at risk and species that aren’t well-studied. Your observations may help track population and distribution changes over time as a result of factors such as climate change. It’s free. -

Order of the Executive Director May 14, 2020

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Park Act Order of the Executive Director TO: Public Notice DATE: May 14, 2020 WHEREAS: A. This Order applies to all Crown land established or continued as a park, conservancy, recreation area, or ecological reserve under the Park Act, the Protected Areas of British Columbia Act or protected areas established under provisions of the Environment and Land Use Act. B. This Order is made in the public interest in response to the COVID-19 pandemic for the purposes of the protection of human health and safety. C. This Order is in regard to all public access, facilities or uses that exist in any of the lands mentioned in Section A above, and includes but is not limited to: campgrounds, day-use areas, trails, playgrounds, shelters, visitor centers, cabins, chalets, lodges, resort areas, group campsites, and all other facilities or lands owned or operated by or on behalf of BC Parks. D. This Order is in replacement of the Order of the Executive Director dated April 8, 2020 and is subject to further amendment, revocation or repeal as necessary to respond to changing circumstances around the COVID-19 pandemic. Exemptions that were issued in relation to the previous Order, and were still in effect, are carried forward and applied to this Order in the same manner and effect. Province of British Columbia Park Act Order of the Executive Director 1 E. The protection of park visitor health, the health of all BC Parks staff, Park Operators, contractors and permittees is the primary consideration in the making of this Order. -

SOME >>NOTABLE THINGS

1928 First Community Museum: Langley (Native SOME Sons & Daughters) >>NOTABLE 1931 First Art Gallery: Vancouver Art Gallery 1932 First Pioneer Museum: Old Hastings Mill THINGS Store (Native Daughters of British Columbia) also called “Museum of B.C. Historical Relics in Memory An Early History of the Pioneers” of the BCMA 1935 First Interior BC Museum: Ashcroft Mu- seum 1937 First Museum and Archives: Kamloops Mu- seum and Archives Lesley Moore 1940 First Official Park of Totem Poles:Thun - Today, from Atlin to Zeballos, and from Archives to Zoos, derbird Park, Victoria the British Columbia Museums Association represents a membership of over 450. In recognition of its first 60 1944 First and only Boy Scouts Museum : Boy years, here are some notable things from the early years. Scouts Museum did not receive a formal name. The There are undoubtedly some errors and omissions for Museum was a “shack” located at the Waterfront which the author asks forgiveness. Park, Kelowna Between 1886 and 1955, the first twenty museums of 1947 First University Museum: UBC Museum of their kind came into being: Anthropology 1886In 1955, First Deputy Provincial Provincial Museum: Secretary The Provincial L. Wallace Museum, and In 1948 First Indigenous Museum: Skeena Treasure located in a room in the “Birdcages” of the Provincial House, Hazelton (later K’san) Legislature 1951 First Gallery on Vancouver Island: Art Gal- 1894 First City Museum:Art, Historical and Scientific lery of Greater Victoria Association, Vancouver 1951 First Museum in the Okanagan: Kelowna -

Managing Visitors in Wilderness Environments Parks Canada's

Managing Visitors in Wilderness Environments Parks Canada’s Western Workshop Surrey, British Columbia B.C. Forestry Association Green Timbers Conference Centre March 17-22,1996 Summary Proceedings Workshop Sponsors Parks Canada Pacific Yukon Region Natural Resources Branch, Ottawa Centre for Tourism Policy and Research School of Resource and Environmental Management Simon Fraser University Editors Alison Davis Siobhan Jackson Pamela Wright, Ph.D. Centre for Tourism Policy and Research School of Resource and Environmental Management Simon Fraser University Managing Visitors in Wilderness Environments, Parks Canada’s Western Workshop Parks Canada, Centre for Tourism Policy and Resear 8380-6/2 Vol. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements.. .l Setting the Stage . .2 Tom Elliot and Pam Wright THE WILDERNESS PARADOX: PERSPECTIVES ON MANAGING WILDERNESS Taking the Ecosystem Perspective. 3 Ken Lertzman, SFU Cultural Resource Management and the Concept of Wilderness . .6 Sandra Zacharias, Deva Heritage Consulting Ltd. APPLYING SCIENCE TO MANAGING WILDERNESS AND THE WILDERNESS EXPERIENCE The Monitoring Context.. .8 Dave Cole, Aldo Leopold Institute Determining Indicators of the Wilderness Experience. .12 Alan Watson, Aldo Leopold Institute Managing Visitor Impacts in the Backcountry.. 14 Dave Cole, Aldo Leopold Institute Monitoring Levels of Use in the Backcountry.. 16 Paul Lauzon, formerly with Calgary Regional Office, Parks Canada PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER: VISITOR MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES AND DECISION MAKING Merging Ecological and Social Science Data: The Jasper River Use Study.. .18 Pam Wright, SFU West Coast Trail User and Willingness to Pay Research . .22 Rick Rollins, Malaspina University College . A Cumulative Effects Assessment (CEA) of Proposed Projects in Kluane National Park Reserve, Yukon Territory . .24 George Hegmann, Axys Environmental Consulting. -

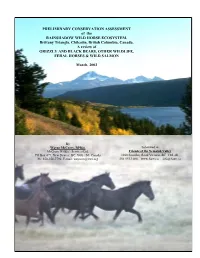

PRELIMINARY CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT of the RAINSHADOW WILD HORSE ECOSYSTEM, Brittany Triangle, Chilcotin, British Columbia, Canada

PRELIMINARY CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT of the RAINSHADOW WILD HORSE ECOSYSTEM, Brittany Triangle, Chilcotin, British Columbia, Canada. A review of GRIZZLY AND BLACK BEARS, OTHER WILDLIFE, FERAL HORSES & WILD SALMON March, 2002 By Wayne McCrory, RPBio. Submitted to McCrory Wildlife Services Ltd. Friends of the Nemaiah Valley PO Box 479, New Denver, BC, V0G 1S0, Canada 1010 Foul Bay Road Victoria, BC V8S 4J1 Ph: 250-358-7796; E-mail: [email protected] 250 592-1088 www.fonv.ca [email protected] i With thanks to the Xeni Gwet’in First Nation for welcoming us on to their traditional territory to carry out this research Xeni Gwet’in Chief Roger William on trail in Brittany Triangle in September, 2001 Suggested Citation: McCrory, W.P. 2002. Preliminary conservation assessment of the Rainshadow Wild Horse Ecosystem, Brittany Triangle, Chilcotin, British Columbia, Canada. A review of grizzly and black bears, other wildlife, wild horses, and wild salmon. Report for Friends of Nemaiah Valley (FONV), 1010 Foul Bay Road, Victoria, B.C. V8S 4J1. [Copies available from FONV at cost. For more information see: http://www.fonv.ca. Copying and distribution of this report are encouraged. Readers are welcome to cite this report but are requested that citations and references be acknowledged and placed in context]. ii One of two wild horse herds studied in Nuntsi Provincial Park in 2001. Hundreds of these small and large meadows are scattered throughout the pine forests of the Brittany Triangle, providing important habitats for wild horses, grizzly and black bears, and other wildlife from spring to fall. Over the long Chilcotin winter, the horses survive on grasses and sedges in these meadow areas as well as pine grass in the adjacent forests. -

Blue-Grey Taildropper (Prophysaon Coeruleum) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Adopted under Section 44 of SARA Recovery Strategy for the Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum) in Canada Blue-grey Taildropper 2018 Recommended citation: Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2018. Recovery Strategy for the Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. 2 parts, 20 pp. + 36 pp. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: © Kristiina Ovaska (with permission) Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de la limace-prophyse bleu-gris (Prophysaon coeruleum) au Canada » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2018. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-660-24535-5 Catalogue no. En3-4/285-2018E-PDF Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 http://sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=24F7211B-1 RECOVERY STRATEGY FOR THE BLUE-GREY TAILDROPPER (Prophysaon coeruleum) IN CANADA 2018 Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada. In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of British Columbia has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the Recovery Plan for Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum) in British Columbia (Part 2) under Section 44 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). -

Welcoming Visitors, Benefiting Locals, Working Together: A

WELCOMING VISITORS – BENEFITING LOCALS – WORKING TOGETHER A STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM IN BRITISH COLUMBIA 2019 – 2021 March 2019 Copyright © 2019, Province of British Columbia All rights reserved. Surfing in Tofino, B.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS MINISTER’S MESSAGE 5 STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK AT A GLANCE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 WELCOMING VISITORS - BENEFITING LOCALS - WORKING TOGETHER A STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM IN B.C. 14 SUPPORTING PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES 16 SUSTAINABLY GROWING THE VISITOR ECONOMY 19 RESPECTING NATURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT 22 MEASURING PROGRESS 25 WORKING TOGETHER 27 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 30 WELCOMING VISITORS - BENEFITING LOCALS - WORKING TOGETHER 3 A STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM IN BRITISH COLUMBIA 2019–2021 Salmon Glacier, near Stewart, B.C. 4 WELCOMING VISITORS - BENEFITING LOCALS - WORKING TOGETHER A STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM IN BRITISH COLUMBIA 2019–2021 MINISTER’S MESSAGE FROM THE HONOURABLE LISA BEARE - MINISTER OF TOURISM, ARTS & CULTURE British As part of our government’s commitment to accessibility Columbia has a and inclusivity, we are working to ensure tourism in B.C. well-deserved is better able to meet the needs of those with varying reputation abilities and aging visitors upholding our values of as a world- diversity, equality and inclusion. class tourism destination. We’ll make sure communities affected by wildfires and People floods are prepared for a quick response and recovery throughout in the future. And we are renewing efforts to support B.C. work in the local events and festivals unique to many of our smaller tourism sector communities. We’ll also leverage the tools available and are proud to address challenges posed by the lack of affordable champions of housing and skilled workers so that people can afford to all our beautiful live and work here. -

DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY TAHSISH-KWOIS PROVINCIAL PARK Photo: Adrian Dorst

NORTH ISLAND DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY TAHSISH-KWOIS PROVINCIAL PARK Photo: Adrian Dorst DESTINATION BC Seppe Mommaerts MANAGER, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT Jody Young SENIOR PROJECT ADVISOR, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT [email protected] TOURISM VANCOUVER ISLAND Calum Matthews COMMUNITY & INDUSTRY SPECIALIST 250 740 1224 [email protected] INDIGENOUS TOURISM BC 604 921 1070 [email protected] MINISTRY OF TOURISM, ARTS AND CULTURE Amber Mattock DIRECTOR, LEGISLATION AND DESTINATION BC GOVERNANCE 250 356 1489 [email protected] NORTH ISLAND | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................1 7. STRATEGY AT A GLANCE ............................................................... 36 II. ACRONYMS ...........................................................................................5 8. STRATEGIC PRIORITIES ...................................................................37 THEME 1: Tourism Infrastructure 1. FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..............................6 THEME 2: Trails and Crown Land Access 2. INTRODUCING THE STRATEGY .....................................................8 THEME 3: Collaboration a. Program Vision and Goals THEME 4: Technology b. Purpose of the Strategy THEME 5: Industry Development c. A Focus on the Supply and Experience THEME 6: Product and Experience Development d. Methodology 9. IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK ............................................. 55 e. Project Outputs a. Catalyst Projects 3. ALIGNMENT ........................................................................................ -

BC Parks and Protected Areas Challenges

Conservation of Species and Ecosystems at Risk: BC Parks and Protected Areas Challenges VICTORIA STEVENS AND LAURA DARLING Protected Areas Recreation and Conservation Section, Parks and Protected Areas Branch, British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, P.O. Box 9398, Stn Prov Govt, Victoria, BC, V8W 9M9, Canada, email [email protected] Abstract: There are six interrelated challenges to managing species and ecosystems at risk within British Columbia’s protected areas system: (1) the history of goals for park acquisitions, (2) the 12% goal for the protected land base, (3) the fragmentation inherent in a system that represents all ecological zones, (4) the dual mandate of conservation and recreation, (5) the need for recognition that protected areas do not have inherent integrity and therefore require management, and (6) the need for management of protected areas as part of the landscape beyond protected area boundaries. Each of these challenges is discussed in this paper. Key Words: challenges, management, protected areas, conservation, integration, British Columbia Introduction A variety of challenges face protected areas managers in British Columbia (B.C.). The six listed below are the primary challenges for those with the mandate to manage and protect conservation values including species and ecosystems at risk: 1. the history of goals for park acquisitions, 2. the 12% goal for the protected land base, 3. the fragmentation inherent in a system that represents all ecological zones, 4. the dual mandate of conservation and recreation, 5. the need for recognition that protected areas do not have inherent integrity and therefore require management, and 6. -

September October 2006 Vol 63.2 Victoria Natural

SEPTEMBER OCTOBER 2006 VOL 63.2 VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY The Victoria Naturalist Vol. 63.2 (2006) 1 Published six times a year by the VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, SUBMISSIONS P.O. Box 5220, Station B, Victoria, B.C. V8R 6N4 Deadline for next issue: October 1, 2006 Contents © 2006 as credited. Send to: Claudia Copley ISSN 0049—612X Printed in Canada 657 Beaver Lake Road, Victoria BC V8Z 5N9 Editors: Claudia Copley, 479-6622 Phone: 250-479-6622 Penelope Edwards, James Miskelly Fax: 479-6622 e-mail: [email protected] Desktop Publishing: Frances Hunter, 479-1956 Distribution: Tom Gillespie, Phyllis Henderson Printing: Fotoprint, 382-8218 Guidelines for Submissions Opinions expressed by contributors to The Victoria Naturalist Members are encouraged to submit articles, field trip reports, natural his- are not necessarily those of the Society. tory notes, and book reviews with photographs or illustrations if possible. Photographs of natural history are appreciated along with documentation VICTORIA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY of location, species names and a date. Please label your submission with Honorary Life Members Mrs. Lyndis Davis, Mr. Tony Embleton, your name, address, and phone number and provide a title. We request Mr. Tom Gillespie, Mrs. Peggy Goodwill, Mr. David Stirling, submission of typed, double-spaced copy in an IBM compatible word Mr. Bruce Whittington processing file on diskette, or by e-mail. Photos and slides, and diskettes submitted will be returned if a stamped, self-addressed envelope is in- Officers: 2005-2006 cluded with the material. Digital images are welcome, but they need to PRESIDENT: Ed Pellizzon, 881-1476, [email protected] be high resolution: a minimum of 1200 x 1550 pixels, or 300 dpi at the VICE-PRESIDENT: James Miskelly, 477-0490, [email protected] size of photos in the magazine. -

Victoria and Southern Vancouver Island

Gonzales Hill (Peter Grant) Gonzales Hill 6 Victoria and Southern Vancouver Island Southern Vancouver Island includes Victoria, Sooke (35 kilometres south- west) and the Saanich Peninsula (35 km north). The Strait of Juan de Fuca is at its feet, and the Sooke Hills and Highlands form the backdrop. It’s an area with a remarkable spectrum of climatic conditions — from Sooke’s wet coast feel to Sidney’s rain-shadow heat trap. The traditional home of Salish First Nations, Victoria was where the English colonial project started in 1843. It grew from a little trading depot to include three cities, two towns and eight municipal districts. Victoria has been a seat of govern- ment since 1849 and the capital of British Columbia since 1868. Esquimalt has had a naval base since the 1850s. A host of outstanding cultural and heritage sites are based on these twin heritages. The economic wealth reflected in the area’s fine homes, gardens and restaurants is matched by the riches of its parks and natural areas — within hailing distance of the 375,000 people who call it home. Songhees Point 1 The austere simplicity of ancient rock gives Songhees Point, on the west side of Victoria’s Inner Harbour, an elemental character. It is a fitting place 7 to contemplate the history of Victoria’s First Nations. A bronze sculpture represents a spindle whorl, an icon of the Coast Salish people and an important piece of traditional Salish wool-spinning technology. The casting is the work of local First Nations artist Butch Dick. It’s one of seven Signs of Lekwungen installed around Victoria to mark sites of sig- nificance to First Peoples.