America of Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Bank Branch Location Detail by Branch State AR

US Bank Branch Location Detail by Branch State AR AA CENTRAL_ARKANSAS STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 019 99999 9538.00 108.047 Arkadelphia Main Street F 526 Main St Arkadelphia 71923 05 059 99999 0207.00 106.6889 Bismarck AR F 6677 Highway 7 Bismarck 71929 05 059 99999 0204.00 74.9001 Malvern Ash Street F 327 S Ash St Malvern 72104 05 019 99999 9536.01 102.2259 West Pine F 2701 Pine St Arkadelphia 71923 AA FORT_SMITH_AR STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 033 22900 0206.00 110.8144 Alma F 115 Hwy 64 W Alma 72921 05 033 22900 0203.02 116.7655 Pointer Trail F 102 Pointer Trl W Van Buren 72956 05 033 22900 0205.02 61.1586 Van Buren 6th & Webster F 510 Webster St Van Buren 72956 AA HEBER_SPRINGS STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 023 99999 4804.00 114.3719 Heber Springs F 821 W Main St Heber Springs 72543 05 023 99999 4805.02 118.3 Quitman F 6149 Heber Springs Rd W Quitman 721319095 AA HOT_SPRINGS_AR STATE CNTY MSA TRACT % Med LOCATION Branch ADDRESS CITY ZIP CODE CODE CODE Income Type 05 051 26300 0120.02 112.1492 Highway 7 North F 101 Cooper Cir Hot Springs Village 71909 05 051 26300 0112.00 124.5881 Highway 70 West F 1768 Airport Rd Hot Springs 71913 05 051 26300 0114.00 45.0681 Hot Springs Central Avenue F 1234 Central Ave Hot Springs 71901 05 051 26300 0117.00 108.4234 Hot Springs Mall F 4451 Central Ave Hot Springs 71913 05 051 26300 0116.01 156.8431 Malvern Avenue F -

HISTORIC LEWISTON: a Self-Guided Tour of Our History, Architecture And

HISTORIC LEWISTON: A self-guided tour of our history, architecture and culture Prepared by The Historic Preservation Review Board City of Lewiston, Maine August 2001 Sources include National Register nomination forms, Mill System District survey work by Christopher W. Closs, Downtown Development District Preservation Plan by Russell Wright, and surveys by Lewiston Historic Commission, as well as original research. This publication has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. The Maine Historic Preservation Commission receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or handicap in its federally assisted program. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U. S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. 20240. Lewiston Mill System District A. Lewiston Bleachery and Dye Works (Pepperell Associates): c. 1876. Built by the Franklin Company to provide finishing operations for associated Lewiston mills; now contains 18 buildings. Pepperell Associates assumed ownership in the 1920's and added the sheet factory on Willow Street in 1929. -

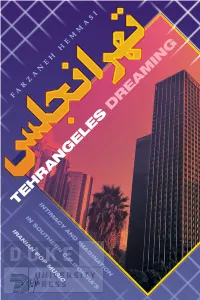

Read the Introduction

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

Non-Oxygenated Gas List

MSRA Legislative Committee Extra May 2012 These are stations that provide non-oxygenated (ethanol free) gasoline in Minnesota & Wisconsin . Please patronize these stations during the cruising season & year-round with your daily drivers. Remind them that we count on them for non-oxygenated fuel for our collector cars & be sure to thank them for carrying non-oxy fuel. *Please contact a Legislative Committee member if: Non-Oxy *You know of a station that carries non-oxy & is not on this list . To add a station to the list, the station Fuel phone number is required so we can call to verify all information. *You see a station on this list that no longer carries non-oxy or if you see any errors on the list . Go to www.msra.com for a list of the Legislative Committee Members. This list is sorted first by city, then alphabetical by station, to make it easy to locate stations as you travel. A drian Co-op Oil Co. SuperAmerica Cenex Bill’s Superette 221 N. Main 750 West Main Street 840 East Main St 6290 Boone Ave. No. Adrian, MN 56110 Anoka, MN 55303 Belle Plaine, MN 56011 Brooklyn Park, MN 55428 507-483-2734 763-421-6590 952-873-3344 763-535-8394 Paulbeck’s County Market Marathon River Dick’s North Side Inc. Bill’s Superette 171 Red Oak Drive Country CO-OP 100 Paul Bunyan Drive NW 3100 Brookdale Dr. No. Aitkin, MN 56431 15050 Galaxie Avenue Bemidji, MN 56601 Brooklyn Park, MN 55443 218-927-2987 Apple Valley, MN 55124 218-751-2979 763-566-5102 952-891-2945 Station 66 Holiday Station Store Ben’s Super Service and Bait 140 Railroad Avenue Valley Oil Co. -

Distributor Settlement Agreement

DISTRIBUTORS’ 7.30.21 EXHIBIT UPDATES DISTRIBUTOR SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT DISTRIBUTORS’ 7.30.21 EXHIBIT UPDATES Table of Contents Page I. Definitions............................................................................................................................1 II. Participation by States and Condition to Preliminary Agreement .....................................13 III. Injunctive Relief .................................................................................................................13 IV. Settlement Payments ..........................................................................................................13 V. Allocation and Use of Settlement Payments ......................................................................28 VI. Enforcement .......................................................................................................................34 VII. Participation by Subdivisions ............................................................................................40 VIII. Condition to Effectiveness of Agreement and Filing of Consent Judgment .....................42 IX. Additional Restitution ........................................................................................................44 X. Plaintiffs’ Attorneys’ Fees and Costs ................................................................................44 XI. Release ...............................................................................................................................44 XII. Later Litigating -

PORTNAME COUNTRYNAME SECTORNAME Kabul Afghanistan Asia Algiers Algeria Africa Annaba Algeria Africa Bejaia Algeria Africa Oran A

PORTNAME COUNTRYNAME SECTORNAME Kabul Afghanistan Asia Algiers Algeria Africa Annaba Algeria Africa Bejaia Algeria Africa Oran Algeria Africa Skikda Algeria Africa Kralendijk Andorra Europe Cabinda Angola Africa Lobito Angola Africa Luanda Angola Africa Malongo Angola Africa Namibe Angola Africa Soyo Angola Africa St Johns Anguilla South America The Valley Anguilla South America St.Johns [AG] Antigua South America Ushuaia Argentina South America Buenos Aires Argentina South America Puerto Madryn Argentina South America San Pedro Argentina South America Victoria Argentina South America Bahia Blanca Argentina South America Mendoza Argentina South America Puerto Deseado Argentina South America Mar del Plata Argentina South America San Antonio Este (Rio Negro) Argentina South America Yerevan Armenia Europe Oranjestad Aruba South America Broken Tooth Ascension Island South America Comfortless Cove Ascension Island South America Georgetown [AI] Ascension Island South America Adelaide Australia Australia & New Zealand Darwin Australia Australia & New Zealand Burnie Australia Australia & New Zealand Brisbane Australia Australia & New Zealand Freemantle Australia Australia & New Zealand Hobart Australia Australia & New Zealand Melbourne Australia Australia & New Zealand Sydney Australia Australia & New Zealand Tasmania Australia Australia & New Zealand Torres Strait Australia Australia & New Zealand Townsville Australia Australia & New Zealand Devonport Australia Australia & New Zealand Launceston Australia Australia & New Zealand Gladstone Australia -

NOTIFICATION of PENDING ACCREDITATION ACTIONS March 2021 Commission Meeting

NOTIFICATION OF PENDING ACCREDITATION ACTIONS March 2021 Commission Meeting MEMBERSHIP ACTIONS Candidate for Accreditation Institution: Main Campus ID, Name, and Address Adult Education Center 4260 Westgate Avenue West Palm Beach, FL 33409 Belmont Correctional Institution – Candidate for Accreditation 68518 Bannock Road, SR 331 St. Clairsville, OH 43950 East Los Angeles Occupational Center 2100 Marengo Street Los Angeles, CA 90033 Klassic Transformations Barber Academy 298 SW Blue Parkway Lee Summit’s MO 64063 Ohio Reformatory for Women 1479 Collins Avenue Marysville, OH 43040 Richland Correctional Institution 1001 Olivesburg Road Mansfield, OH 41904 Initial Accreditation Institution: Main Campus ID, Name, and Address 342200 American Business and Technical College #85 Mendez Vigo Street, Corner Guadalupe Street Ponce, PR 00730 354700 EK Professionals Microblading & Permanent Cosmetics Institute 11908 Kanis Road, Suite G6 Little Rock, AR 72211 332900 Maplewood Career Center 7075 State Route 88 Ravenna, OH 44266 356900 Medical Solutions Academy 306 Poplar Street Danville, VA 24541 351500 Top of the Line Barber School 2306 Austin Hwy San Antonio, TX 78218 356000 Upper Kutz Barber & Style College 813 Highway 1 South Greenville, MS 38701 356500 U.S. Army Recruiting and Retention College 1929 Old Ironsides Avenue Fort Knox, KY 40121 354300 Washington DC Joint Plumbing Apprenticeship Committee 5000 Forbes Boulevard Lanham, MD 20706 1 Reaffirmation of Accreditation Institution: Main Campus ID, Name, and Address 327200 Academy of Interactive Entertainment -

European Identity

Peaceful, prosperous, democratic and respectful of people’s rights, building talk about Europe need to We Europe is an ongoing challenge. For many years it seemed that Europeans lived on a continent of shared values and a common destiny. No one paid attention to the alarm bells warning of growing divisions across the continent, which have become more insistent since the economic and social crisis. Europe and We need to talk its values, previously taken for granted, are now being contested. These clouds are casting a shadow across Europe’s future, and old demons, long dormant, have started to raise their voices again. about Europe With a deepening values divide there is an urgent need for public debate and a reconsideration of how Europeans can strengthen the European project. Is a “Europe united in diversity” still feasible? Can a consensus be forged on a set of values pertaining to a common European identity? What should be done to preserve European unity? The Council of Europe, with its membership covering Europe from Vladivostok to Lisbon and from Reykjavik to Ankara, and its mission to promote democracy, human rights and the rule of law, provides an excellent framework for discuss- ing the current state of thinking and dynamics behind the concept of European identity. For these reasons, the Council of Europe, together with the École nationale d’administration in Strasbourg, held a series of European Identity Debates fea- turing eminent personalities from a variety of backgrounds including politics, civil society, academia and the humanities. European Identity This publication presents the 10 European Identity Debates lectures. -

Why Are the Twin Cities So Segregated?

Why Are the Twin Cities So Segregated? February, 2015 Executive Summary Why are the Twin Cities so segregated? The Minneapolis-Saint Paul metropolitan area is known for its progressive politics and forward-thinking approach to regional planning, but these features have not prevented the formation of the some of the nation’s widest racial disparities, and the nation’s worst segregation in a predominantly white area. On measures of educational and residential integration, the Twin Cities region has rapidly diverged from other regions with similar demographics, such as Portland or Seattle. Since the start of the twenty-first century, the number of severely segregated schools in the Twin Cities area has increased more than seven- fold; the population of segregated, high-poverty neighborhoods has tripled. The concentration of black families in low-income areas has grown for over a decade; in Portland and Seattle, it has declined. In 2010, the region had 83 schools made up of 90 percent nonwhite students. Portland had two. The following report explains this paradox. In doing so, it broadly describes the history and structure of two growing industry pressure groups within the Twin Cities political scene: the poverty housing industry (PHI) and the poverty education complex (PEC). It shows how these powerful special interests have worked with local, regional, and state government to preserve the segregated status quo, and in the process have undermined school integration and sabotaged the nation’s most effective regional housing integration program and. Finally, in what should serve as a call to action on civil rights, this report demonstrates how even moderate efforts to achieve racial integration could have dramatically reduced regional segregation and the associated racial disparities. -

Le Forum, Vol. 42 No. 3

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Le FORUM Journal Franco-American Centre Franco-Américain Fall 2020 Le Forum, Vol. 42 No. 3 Lisa Desjardins Michaud, Rédactrice Robert B. Perreault Gérard Coulombe Timothy St. Pierre Lise Pelletier See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/francoamericain_forum This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Le FORUM Journal by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Lisa Desjardins Michaud, Rédactrice; Robert B. Perreault; Gérard Coulombe; Timothy St. Pierre; Lise Pelletier; James Myall; Julianna L'Heureux; Linda Gerard DerSimonian; Marie-Anne Gauvin; Wilfred H. Bergeron; Patrick Lacroix; Suzanne Beebe; Steven Riel; Michael Guignard; Clément Thierry; and Virginie L. Sand Le FORUM “AFIN D’ÊTRE EN PLEINE POSSESSION DE SES MOYENS” VOLUME 42, #3 FALL/AUTOMNE 2020 Paul Cyr Photography: https://paulcyr.zenfolio.com Websites: Le Forum: http://umaine.edu/francoamerican/le-forum/ https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/francoamericain_forum/ Oral History: https://video.maine.edu/channel/Oral+Histories/101838251 Library: francolib.francoamerican.org Occasional Papers: http://umaine.edu/francoamerican/occasional-papers/ Résonance, Franco-American Literary Journal: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/resonance/vol1/iss1/ other pertinent websites to check out - Les Français d’Amérique / French In America Calendar Photos and Texts from 1985 to 2002 http://www.johnfishersr.net/french_in_america_calendar.html Franco-American Women’s Institute: http://www.fawi.net $6.00 Le Forum Sommaire/Contents L’État du ME.....................................4-20 L’État du NH..................................21-33 The Novitiate in Winthrop, Maine.........4-7 Portrait Claire Quintal se raconte ............. -

America's Sweethearts

America's Sweethearts Dir: Joe Roth, 2001 A review by A. Mary Murphy, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada The whole idea of America's Sweethearts is to have a little fun with the industry of film stars' lives, and the fact that their marriages, breakdowns and breakups have become an entertainment medium of their own. Further to this is the fact that not only does the consumer buy the product of stars' off-screen lives, but so (at times) do stars. Of course, part of the fun of this film is that it just happens to be populated by some very large careers, which makes for good box-office (and ironic) appeal -- with Julia Roberts, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Billy Crystal, and John Cusack as the front-line members of the cast. Everyone should be thoroughly convinced by now that Julia Roberts was born to play romantic comedy. Those liquid eyes and that blazing smile go directly to an audience's collective heart, and make it leap or ache as required. On the occasions when she steps out of her generic specialty, it's just an embarrassment (for example Mary Reilly [1996]); and reminds us that she is not a great dramatic actor -- the Academy Award notwithstanding. However, when Roberts stays within her limits, and does what she is undeniably talented at doing, there's nobody better. She's not the only big-name actress in America's Sweethearts, so she doesn't get all the screen time she's accustomed to, but she makes good use of her allotment. However, there are a couple of problems with the premise for her character, Kiki. -

Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity Delia Walker-Jones Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Geography Honors Projects Geography Department 4-26-2017 Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity Delia Walker-Jones Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/geography_honors Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Walker-Jones, Delia, "Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity" (2017). Geography Honors Projects. 52. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/geography_honors/52 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geography Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity Delia Walker-Jones Macalester College Advisor: Professor Holly Barcus Geography Department 04/26/2017 CONFERENCE OF THE BIRDS 1 Abstract The United States is home to the largest population of Iranians outside of Iran, an immigrant group that slowly emerged over the latter half of the 20th century, spurred by the 1979 Iranian Revolution and subsequent unrest in the mid-2000s. This case study explores the Iranian and Iranian-American-identifying population of the United States, with a geographic focus on the Twin Cities metro area in Minnesota. It delves into several