European Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year in Review 2008

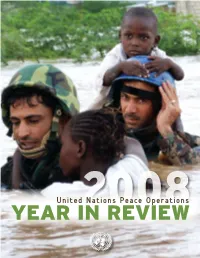

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Interoperability and the Visa Procedure - Possible Implications of Interoperability on the Daily Work of the Consulates - Presentations

Brussels, 10 July 2019 WK 8371/2019 INIT LIMITE VISA DAPIX SIRIS FRONT COMIX WORKING PAPER This is a paper intended for a specific community of recipients. Handling and further distribution are under the sole responsibility of community members. MEETING DOCUMENT From: General Secretariat of the Council To: Visa Working Party Subject: Interoperability and the visa procedure - Possible implications of Interoperability on the daily work of the consulates - Presentations Delegations will find attached the presentations made by the Commission services, eu-LISA and the Presidency on the abovementioned subject at the Visa Working Party meeting on 10 July 2019. WK 8371/2019 INIT LIMITE EN The interoperability between EU information systems Presentation in the VISA WP 10 July 2019 [email protected] European Commission – Directorate-General Migration & Home Affairs Unit B3 – Information Systems for Borders and Security EU Information systems & Interoperability • Interoperability proposals: Decembre 2017 • The Regulations were adopted on 20 May 2019 and published on 22 May 2019 (Regulations (EU) 2019/817 and 2019/818) • Interoperability between EU information systems operated at the EU central level. • Interoperability is about making the systems talk to each other and work together in a smarter way • Each system has its own objectives, purposes, legal bases, rules, user groups and institutional context. Interoperability does not change that. ECRIS SIS EES VIS ETIAS Eurodac -TCN 2 EU Information systems & Interoperability ECRIS -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ...z w ~ ~ ~ w C ..... Z w ~ oQ. -'w >w Public Disclosure Authorized C -' -ct ou V') Public Disclosure Authorized " Public Disclosure Authorized VIOLENCE PREVENTION A Critical Dimension of Development Background 2 Agenda 4 Participant Biographies 10 Photo Contest Imagining Peace 32 Photo Contest Winners 33 Photo Contest Finalists 36 Conference Organizing Team & Contact Information 43 The Conflict, Crime and Violence team in the Social high levels of violent crime, street violence, do Development Department (SDV) has organized a mestic violence, and other kinds of violence. day and a half event focusing on "Violence Pre vention: A Critical Dimension of Development". Violence takes many forms: from the traditional As the issue of violence crosscuts other agendas protection racket by illegal organizations to the of the World Bank, the objectives of the event are rise of international illegal trafficking (arms, hu to raise World Bank staff's awareness of the link mans, drugs), from gang-based urban violence between violence prevention and development, its and crime to politically-motivated violence fueled relevance for development, and to present the ra by socio-economic grievances. All these forms of tionale for increased attention to violence preven violence concur to erode the well-being of all- and tion and reduction within World Bank operations. more acutely of the poorest - and to stymie devel opment efforts. Social failure, weak institutional Violence has become one of the most salient de capacity and the lack of a legal framework to pro velopmental issues in the global agenda. Its nega tect and guarantee people's safety and rights cre tive impact on social and economic development ate a climate of lawlessness and engender dynam in countries across the world has been well doc ics of state-within-state behavior by increasingly umented. -

Visa Information System Supervision Coordination Group Joint Activity

Coordinated Supervision of VIS Activity Report 2012-2014 Secretariat of the VIS Supervision Coordination Group European Data Protection Supervisor Postal address: Rue Wiertz 60, B-1047 Brussels Office address: Rue Montoyer 30, 1000 Brussels email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction and background .............................................................................................. 3 2. Organisation of coordinated supervision ............................................................................ 4 2.1. Main principles ............................................................................................................... 4 2.2. The supervision coordination meetings .......................................................................... 4 3. 2012-2014: Issues discussed and achievements ................................................................. 6 3.1. Common framework for inspections .............................................................................. 6 3.2. Use of ESPs for the processing of visa applications ....................................................... 7 3.3. Questionnaires................................................................................................................. 8 4. Members' Reports ............................................................................................................... 8 4.1. Austria ............................................................................................................................. 8 4.2. -

Values for the Future : the Role of Ethics in European and Global Governance

#EthicsGroup_EU Values for the Future : The Role of Ethics in European and Global Governance European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies Research and Innovation European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies Values for the Future: The Role of Ethics in European and Global Governance European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation Unit 03 Contact Jim DRATWA Email [email protected] [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels Manuscript completed in May 2021. The European Commission is not liable for any consequence stemming from the reuse of this publication. The contents of this opinion are the sole responsibility of the European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (EGE). The views expressed in this document reflect the collective view of the EGE and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission. This is an EGE Statement, adopted by the members of the EGE: Emmanuel Agius, Anne Cambon-Thomsen, Ana Sofia Carvalho, Eugenijus Gefenas, Julian Kinderlerer, Andreas Kurtz, Herman Nys (Vice-Chair), Siobhán O’Sullivan (Vice-Chair), Laura Palazzani, Barbara Prainsack, Carlos Maria Romeo Casabona, Nils-Eric Sahlin, Jeroen van den Hoven, Christiane Woopen (Chair). Rapporteur: Jeroen van den Hoven. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). PDF ISBN 978-92-76-37870-9 doi:10.2777/595827 KI-08-21-136-EN-N Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021 © European Union, 2021 The reuse policy of European Commission documents is implemented based on Commission Decision 2011/833/EU of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. -

FUTURE of JUSTICE: STRENGTHENING the RULE of LAW Independence, Quality and Efficiency of National Justice Systems and the Importance of a Fair Trial

Finland's Presidency of the Council of the European Union EU 2019.FI Informal meeting of Justice and Home Affairs Ministers, 18-19 July 2019, Helsinki Working session I of Justice Ministers on 19 July 2019 FUTURE OF JUSTICE: STRENGTHENING THE RULE OF LAW Independence, quality and efficiency of national justice systems and the importance of a fair trial Protecting citizens and freedoms is the first priority of the new strategic Agenda for the Union 2019-2024, adopted by the June European Council. According to the Agenda, the EU will defend the fundamental rights and freedoms of its citizens, as recognised in the Treaties, and protect them against existing and emerging threats. Common values underpinning our democratic and societal models are the foundation of European freedom, security and prosperity. The rule of law, with its crucial role in all our democracies, is a key guarantor that these values are well protected; it must be fully respected by all Member States and the EU. A strong common value base makes it possible for the EU to reach its goals and ensure the rights of citizens and businesses. It is only by acting together and defending our common values that the EU can tackle the major challenges of our time while promoting the well-being and prosperity of its citizens. The rule of law is the core foundation of the European Union; it is one of the common values of the Union and as such is enshrined in the Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). The EU Treaties require effective judicial protection as a concrete expression of the value of the rule of law (Article 19(1) TEU), as underlined by the Court of Justice of the European Union in its recent case-law. -

Press Release 07-07-2021 - 08:30 20210701IPR07507

Press release 07-07-2021 - 08:30 20210701IPR07507 EP Today Wednesday, 7 July Live coverage of debates and votes can be found on Parliament’s webstreaming and on EbS+. For detailed information on the session, please also see our newsletter. All information regarding plenary, including speakers’ lists, can be found here. Rights of LGBTIQ persons/Rule of law in Poland and Hungary The risk of discrimination against LGBTIQ citizens in Hungary will be considered in a debate with European Commission Vice-President for Values Vera Jourová and the Slovenian Foreign Affairs Minister Anže Logar. MEPs will also look into the general situation of the rule of law and fundamental rights in both Hungary and Poland. Plenary will vote on a resolution on the rights of LGBTIQ persons in Hungary on Thursday. Polona TEDESKO (+32) 470 88 42 82 EP_Justice Reinforcing the European Medicines Agency Parliament will debate with Health Commissioner Kyriakides a proposal to strengthen the European Medicines Agency, following from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. MEPs are set to call for a new Medicines Supply Database to avoid medicines shortages, and to increase transparency and the availability of public information about clinical trials. Plenary will vote on the negotiating mandate for talks with the Council on Thursday. Dana POPP (+32) 470 95 17 07 EP_Environment Press Service, Directorate General for Communication 1 I 3 European Parliament - Spokesperson: Jaume Duch Guillot EN Press switchboard number (32-2) 28 33000 Press release Debate with Michel and von der Leyen on the last European summit Starting at 9.00, MEPs will discuss the outcome of the 24-25 European Council with Presidents Charles Michel and Ursula von der Leyen. -

The Collection of Polish Art | 1 Right from the Start Artymowska Worked on Abstract Paintings, and Created Monotypes and Ceramics

KunstmThe Bochumuseum Art Bochum Museum – Die– the Sammlung Collection of Polish Art polnischerSelection and texts: Axel Kunst Feuß Multiplied Space IX, 1981 Artymowska, Zofia (1923 Kraków - 2000 Warsaw): Multiplied Space IX, 1981. Serigraphy, Collage, 60.8 x 49.7 cm (41.6 x 41.1 cm); Inv. no. 2149 The Bochum Art Museum Zofia Artymowska, born 1923 in Kraków, died 2000 in Warsaw. She was married to the painter and graphic artist Roman Artymowski (1919-1993). Studies: 1945-50 Academy of Visual Arts, Kraków (under Eugeniusz Eibisch, diploma in painting). 1950/51 Assistant. Lived in Warsaw from 1951; in Łowicz from 1980. 1953-56 works on murals during the reconstruction of Warsaw. 1954 Golden Cross of Merit. 1960-68 Professor at the University of Baghdad. 1971-83 Lecturer at the University of Visual Arts, Breslau/Wrocław. Solo exhibitions since 1959 in Warsaw, Beirut, Baghdad, Łódź, Breslau, Stettin/Szczecin, New York. Works in museums in Baghdad, Bochum, Bogota, Breslau, Bydgoszcz, Dresden, Łódź, New York, Warsaw. The Bochum Art Museum – the Collection of Polish Art | 1 Right from the start Artymowska worked on abstract paintings, and created monotypes and ceramics. During her time in Baghdad she turned to oil painting. At the university there she taught mural painting at Tahreer College as well as painting, drawing and composition at the College of Engineering in the faculty of architecture. From the 1970s onwards she explored the potential forms of expression inherent in a single geometric form, the cylinder (derived from machine parts) that she used as a constantly duplicated module for creating images. -

World Values Surveys and European Values Surveys, 1999-2001 User Guide and Codebook

ICPSR 3975 World Values Surveys and European Values Surveys, 1999-2001 User Guide and Codebook Ronald Inglehart et al. University of Michigan Institute for Social Research First ICPSR Version May 2004 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 www.icpsr.umich.edu Terms of Use Bibliographic Citation: Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: Inglehart, Ronald, et al. WORLD VALUES SURVEYS AND EUROPEAN VALUES SURVEYS, 1999-2001 [Computer file]. ICPSR version. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research [producer], 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2004. Request for Information on To provide funding agencies with essential information about use of Use of ICPSR Resources: archival resources and to facilitate the exchange of information about ICPSR participants' research activities, users of ICPSR data are requested to send to ICPSR bibliographic citations for each completed manuscript or thesis abstract. Visit the ICPSR Web site for more information on submitting citations. Data Disclaimer: The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for uses of this collection or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. Responsible Use In preparing data for public release, ICPSR performs a number of Statement: procedures to ensure that the identity of research subjects cannot be disclosed. -

In Search of Common Values Amid Large-Scale Immigrant Integration Pressures

In Search of Common Values amid Large-Scale Immigrant Integration Pressures Integration Futures Working Group By Natalia Banulescu-Bogdan and Meghan Benton MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE EUROPE In Search of Common Values amid Large-Scale Immigrant Integration Pressures By Natalia Banulescu-Bogdan and Meghan Benton June 2017 Integration Futures Working Group ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was commissioned for a meeting of the Integration Futures Working Group held in Vienna in January 2017. The theme of the meeting was ‘Debating Values: Immigrant Integration in a Time of Social Change’, and this report was among those that in- formed the working group’s discussions. The authors are grateful for the feedback they received from the working group, as well as to Aliyyah Ahad for research assistance and to Elizabeth Collett and Lauren Shaw for their helpful edits and suggestions. The Integration Futures Working Group is a Migration Policy Institute Europe initiative that brings together senior policymakers, experts, civil-society officials, and private-sector leaders to stimulate new thinking on integration policy. It is supported by the Robert Bosch Foundation. For more on the Integration Futures Working Group, visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/integration-futures-working-group. © 2017 Migration Policy Institute Europe. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: April Siruno, MPI Typesetting: Liz Heimann, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is avail- able for free download from www.migrationpolicy.org. -

Rehabilitating the Witch: the Literary Representation of the Witch

RICE UNIVERSITY Rehabilitating the Witch: The Literary Representation of the Witch from the Malleus Maleficarum to Les Enfants du sabbat by Lisa Travis Blomquist A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE Dr. Bernard Aresu Dr. Elias Bongmba, Professor ofRe · ious Studies Holder of the Harry and Hazel Chavanne Chair in Christian Theology HOUSTON, TX DECEMBER 2011 ABSTRACT Rehabilitating the Witch: The Literary Representation of the Witch from the Malleus Maleficarum to Les Enfants du sabbat by Lisa Travis Blomquist The representation of the witch in French literature has evolved considerably over the centuries. While originally portrayed as a benevolent and caring healer in works by Marie de France, Chretien de Troyes, and the anonymous author of Amadas et Ydoine, the witch eventually underwent a dramatic and unfortunate transformation. By the fifteenth century, authors began to portray her as a malevolent and dangerous agent of the Christian Devil. Martin Le Franc, Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay, Fran9ois Rabelais, and Pierre Comeille all created evil witch figures that corresponded with this new definition. It was not until the eighteenth century, through the works of Voltaire and the Encyclopedistes, that the rehabilitation of the witch began. By the twentieth century, Anne Hebert, Jean-Paul Sartre, Maryse Conde, and Sebastiano Vassalli began to rewrite the witch character by engaging in a process of demystification and by demonstrating that the "witch" was really just a victim of the society in which she lived. These authors humanized their witch figures by concentrating on the victimization of their witch protagonists and by exposing the ways in which their fictional societies unjustly created identities for their witch protagonists that were based on false judgments and rumors. -

Auction House KANERZ ART PUBLIC SALE PRESTIGE ITEMS

Auction House KANERZ ART PUBLIC SALE PRESTIGE ITEMS On the occasion of this sale, it will be scattered high quality objects: Majorelle furniture, Design items from the 50s to the 90s, jewelry (gold, rings, watches), fashion accessories (scarves, shoes ), paintings including many Luxembourg works (Trémont, Weis, Brandy, Thilmany, Gerson, Maas, Beckius, Steffen ...), Ivory tusks, objects of curiosity, Far Eastern art, etc. Saturday, November 10th, 2018 At 2 PM The sale is broadcast live with possibility of online auction on Exhibition of the lots: Wednesday 7Th November from 10 AM to 4 PM, Thursday 8th and Friday 9th, November from 10 AM to 6 PM, without interruption. All the lots are in photo on the site of the House of sale: www.encheres-luxembourg.lu Contact : [email protected] GSM : (+352) 621.612.226 Place of the sale: 35 Rue Kennedy, L-7333 Steinsel Free Parking Photos, pre-orders and general conditions of sale can be found on the website of the auction house KANERZ ART at www.encheres-luxembourg.lu. The sale is broadcast live with possibility of online and live auction on www.auction.fr Maison de Ventes KANERZ ART The visits will be an opportunity for buyers to get a clear idea of the desired objects beyond the formal description of the catalog. You will find on the site of the house of sale a form of order of purchases if you cannot attend the sale but that you wish to acquire an object. The sale is also broadcast with the possibility of bidding live or placing orders on the platform www.auction.fr (registration required before + 3% additional fees via this platform).