USTAD ALLAUDDIN KHAN Rajendra Shankar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IME Annual Report 2020-2021 Low Size

Supported by Annual Report 2020-2021 Only in the darkness can “ you see the stars. ― Martin Luther King “ Namaste We have collectively endured one of the defining experiences of our life and times. What started off as a pause in the hustle and bustle of daily life has now become a happening that will forever define the way we see the world. Many of us experienced loss – of loved ones, of time, of precious moments, and of a sense of normalcy. There were days when I questioned everything, and felt the meaninglessness of it all. At the same time, I realized that the future is built one day at a time, by the seemingly small actions we take each day; that, as Martin Luther King said, everything that is done in the world is done by hope. And so, we see ourselves looking back at a most strange year, but one that I am glad to report has been extremely productive for the Indian Music Experience Museum, in our mission to build community through music. The team at IME seamlessly adapted to the online world. We ensured the continuity of music education at the Learning Centre. We unveiled two new online exhibits through an important partnership with Google Art and Culture. Our work in preserving musical traditions achieved an important milestone through the creation of an online archive on the life and works of legendary violinist and composer, Mysore T. Chowdiah, in collaboration with the Shankar Mahadevan Academy. We presented a wide variety of talks, discussions, workshops, showcases, and exhibit walkthroughs online, growing our audience beyond the geographic limitations of in-person events. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

University of Mumbai Department of Music Sample of MCQ Question Paper for Students M.Mus Part 2 Paper -V Course Name – Music

University of Mumbai Department of Music Sample of MCQ Question Paper for Students M.mus part 2 paper -V Course Name – Music Education Paper/Subject Code_________ Student’s Seat No._____ Instrructions; 1. All the Questions are Compulsory Total Marks – 50 2. All Questions Carry Equal Marks 1. Name the artist from Kirana Gharana among the following a. Sangmeshwar Gurav b. Mallikarjun Mansoor c. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit d. Faiyyaz Khan 2. Name the student of Ustad Allauddin Khan a. Ust. Aliakbar Khan b. Kishore Kumar c. Gayatri Chitre d. MAnik Varma 3. Name disciple of Ust. Alladiya Khan among the following a. Kesarbai b. Hirabai c. Begam Akhtar d. Parveen Sultana 4. Where the Indira Kala Vishwavidyalay is Located? a. Pune b. Mumbai c. Khairagadh d. Nagpur 5. Among following who is awarded with Padmavibhushan? a. Pt. Rakesh Chaurasia b. Pt. Jasraj c. Pt. Mukund Lath d. Sumitra Guha 6. Who was the Guru of Kumar Gandharva? a. Saraswati Rane b. B.R. Deodhar c. Kagalkar buwa d. Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale 7. Who had written book on Aesthetics of Indian Music? a. Sudheer Nayak b. Manjiri Sinha c. Rama Deodhar d. Ashok D. Ranade 8. Among the following which is a performing art? a. Natya b. Pottery c. Poetry d. Sculpture 9. Who was titled as Swarbhaskar ? a. Prabhakar Karekar b. Vinay Mishra c. Rajan Sajan Mishra d. Bhimsen Joshi 10. Who was the only direct disciple of Kesarbai Kerkar? a. Dhondutai Kulkarni b. Parmeshwar Hegade c. Pahadi Sanyal d. Jaimala Shiledar 11. Name the famous stage actor-singer a. Saleel Choudhari b. -

Chapter 1 Uday Shankar and Locating Modernity

CHAPTER 1 UDAY SHANKAR AND LOCATING MODERNITY In 1920, a twenty year old, handsome Indian student arrived in London to study painting at the Royal College of Art. Three years later, he made his debut at Covent Garden alongside the legendary Russian ballet dancer, Anna Pavlova, although—quite remarkably—until a few months earlier, he had little to no dance experience. His audiences in England, France, and the United States nevertheless thought he was very talented at what he did. The dancer invented a new style of dance, which purportedly represented Indian culture; his dance looked “foreign” enough that nobody doubted his claim. In the late 1920s, the dancer returned to India, and demonstrated his new style to his fellow compatriots. Most of his compatriots did not care for this new style, but a few prominent figures encouraged him to continue with what he was doing. His family and friends also supported him; some of them even joined his dance troupe as dancers and musicians, including his youngest brother, twenty years his junior. The troupe then returned to Paris. Meanwhile, India was nearing the end of its dramatic transition from a British imperial colony to a newly independent nation. When the dancer returned to settle in India in the late 1930s, he immersed himself in the current debates over India’s future identity and culture. Most people, who believed the essence of Indian culture could be found in its ancient traditions, were looking to the past for the “real” definition of national culture and identity. The dancer, however, proposed that his invented style and eclectic approach to art defined India’s culture instead. -

The Great Musician SD Burman

JUNE 2018 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 1 www.Asia Times.US Globally Recognized Editor-in-Chief: Azeem A. Quadeer, M.S., P.E. JUNE 2018 Vol 9, Issue 6 Punjab govt backs agitating farmers, Sidhu slams Centre The Punjab government came out in support of the state’s agitating farmers as minister ises, the farmers would not have been in Navjot Singh Sidhu slammed the Centre for ignoring the agriculture sector. such a sorry state of affairs. Sidhu assured the protesting farmers that A 10-day long nationwide agitation against the alleged anti-farmer practices of the Union the Punjab government was sympathetic government began today and as part of the protest, the supply of vegetables, fruits, milk to their demands and stood shoulder to and other items to various parts of Punjab and Haryana was stopped. shoulder with them. The Punjab local bodies and tourism In his unique way, the cricketer-turned-politician visited village Patto along with Con- minister stressed that the Swamina- gress MLAs Kuljit Singh Nagra and Gurpreet Singh and bought milk and vegetables from than Commission report was not being farmers to highlight their significant contribution in the development of the nation. implemented and farmers were not getting adequate price for their crops, leading to “If the country is to be saved then saving farm sector ought to be a priority,” Sidhu said escalation in farmer suicides. adding that if the ruling NDA government at the Centre had fulfilled their pre-poll prom- Suggesting linkage of Minimum Support Price (MSP) of crops with oil prices, the min- ister went on to say that in the last 25 years, oil prices increased twelve fold whereas the MSP increased by only five per cent. -

Winner List – February 2020

3 Bill Payment Rs 250 BMS Voucher - Winner list – February 2020 FULL NAME RAJNISH KUMAR MAURYA PATTABHI SHEKAM SEKAR SURESH VSNM JAYANTI GANAPATHI SUBRAMANIAN CHANDRASEKARAN DIGAMBER PRASAD GAIROLA HEMANTH KUMAR JASMEET ARORA AZIBULLAH ANSARI PARUL SARITA KHUDA BAKHSH PATHAN ABHISHEK KOTHARI UTTAM SINGH KHUZAIMA SHABBIR HUSAIN RAMESH CHAND BAJAJ RAVINDRA C RANE PRATIK KUMAR SURESH AGRAWAL SOMNATH MUKHERJEE MANISH KUMAR SHARMA CHINTHALAPUDI HARIKRISHNA KANAKAM PRANITHA SHYAM NARAYAN YADAV ISMAIL GULAM SALEJEE JT1 MOHZAD F DUBASH JT1 SHAIKH ABDUL RAZZAQ MOHAMMAD KHALED SANTOSH VISHNU YADAV GAUTAMKUMAR VISHANJI CHHEDA KRISHNAMURTHY INGUVA KANDHAKATLA SANDHYA RATHNA G SEKAR RAMAMOHAN REDDY BHEMIREDDY PEEYUSH KHANDURIE HIRANMOY MAZUMDAR DHARAMVEER SINGH JASWANT SINGH ABHISHEK MITTAL MENDAPARA DINESHBHAI JERAMBHAI ROCHELLE ANDREA RODRIGUES HOZEFABHAI SEHRAWALA HASRATUL BEGUM SACHIN KISAN SALUNKHE DIANNE CATHERINE HOOPER SHAILENDRA SINGH NAGARJUNA N JAGPREET KAUR V GOVINDAN GOBINATH GHANSHYAM KUMAWAT PRAMOD KUMAR MOHAMMAD ZAHEER MANSOORI SAMIR KUMAR PODDAR MOHD FAZIL SATPUTE SANJAY G SHANKAR KUMAR N PRADEEP H MAHADIK RISHI GUPTA DEEPAK AHLAWAT BALASUBRAMANYA S AKSHAY AGARWAL MANSOOR KATTOOKARAN ABDUL MANAF MURUGA R FARHAD VORA JAYANT KUMAR SUDIPTA MODAK SHABD SWAROOP KHANNA IVAN PAUL HANSRAJ BRIJVALLABH MAURYA NAINAMOHAMMED S ARSHVI ARVINDBHAI DHAMECHA SOURAV KUMAR PUSHKAR JAIN KOUSHIK BANDYOPADHYAY DEEPAK DEVENDRA TUKARAM PAWAR SUNIL K MUTTA MADHURA SUNIL PANTH PATEL MANTHAN JIVAN DATTATRAY PATHAK BHAVESH SHAH SHAILENDRA KUMAR TIWARI HIRAL BHADRESH -

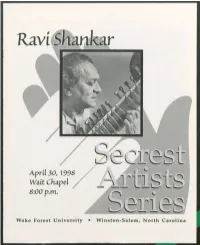

1998 Ravi Shankar Event Program

Aprtl 30, 1998 Wa[t chapel 8:00 p.m. Wake Forest University • Winston-Salem, North Carolina Assisted by Anoushka. shanka.r, sitar Accompanied by Bikram Crhosh,tabla and assistedby Manu Vongre, tamboura Mr. Shankar will announce the program from the stage. There will be one 15 minute intermission WakeForest University expresses its deepappreciation to - 7 Mrs. MarionSecrest and her husband,the late D1'.Willis SeCl'eSt, for generouslyendowing t/ie SecrestArtists Series. North American Agent: Sheldon Soffer Management, Inc., 130 West 56 Street,. New York, NY 10019 212-757-8060 E-mail: [email protected] RAVISHANKAR'S achievements in the Indian music firmament are matched only by his international influence. Fained as the man who popularized Indian music in the West, his life has really been devoted to mu- tual exchange and enlightenment between all nations of the world. George Harrison dubs him the "Godfather of World Music." His 75th birthday was recently commemorated with the release of Ravi:In Celebration,a 4-CD box set spanning his ground-breaking career. He continues to perform in concert halls around the world and is currently readying his autobiography, Raga Mala. He was born Robindra Shankar in Benares, United Province, on April 7, 1920, the youngest of four brothers who survived to adulthood. His father Shyam Shankar was an eminent scholar, statesman, and lawyer but was absent for most of his childhood. The young Shankar (nicknamed "Robu") was therefore raised by his mother in some poverty. His eldest brother, the legendary dancer Uday Shankar, was already in Europe, dancing with Anna Pavolva before establishing his own Indian dance troupe. -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

AWAS PLUS LIST of BLOCK BHADAURA.Xlsx

AAWAS PLUS LIST OF BLOCK BHADAURA , DISTRICT GHAZIPUR S.N. Village Name Registration ID Beneficiary Name Father Or Husband Name Category ik= vik=rk dk dkj.k @ vik= 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 Bareji 142195320 AIYA KHATOON ASLAM Other 2 Bareji 142963726 BHAGMANIYA DEVI HRIDAYA NARAYAN Other 3 Bareji 142963961 BHAGWAN KUSHWAHA KEDAR KUSHWAHA Other 4 Bareji 140446538 FULMMATI DEVI RAMKUMAR Other 5 Bareji 135645078 GAYTRI NANHKU Other 6 Bareji 142963930 KAMALPATIYA DEVI BACHENDRA Other 7 Bareji 135644833 MANATA DEVI BRIJLAL Other 8 Bareji 142963620 MANITA CHAUDHARI SURENDAR CHAUDHRY Other 9 Bareji 135644647 MANJU DEVI DAROGA Other 10 Bareji 142963706 MAYA DEVI PRAHLAD CHAUBE Other 11 Bareji 135644898 MEENA DEVI SINATH Other 12 Rampur Kanwa 146832926 MS URMILA DEVI MOHAN Other 13 Bareji 142963828 NIRASHA DEVI ARVIND KUSHWAHA Other 14 Bareji 142963575 PARBHWATI DEVI JHAGDA Other 15 Bareji 142963852 PREMA DEVI DIGVIJAY KUSHWAHA Other 16 Bareji 142963877 RAJESHWAR CHAUDHARY UMRAV Other 17 Bareji 135644432 RANI DEVI LAL JEE Other 18 Bareji 142963526 REENA DEVI DAROGA UPADHYAY Other 19 Bareji 142963765 SABDEIYA DEVI RAM NARAYAN Other 20 Bareji 142963457 SAHODARI DEVI RAMSHISH CHAUDHRY Other 21 Bareji 142963687 SANGEETA DEVI SANTOSH UPADHYAY Other 22 Bareji 142963899 SARITA DEVI SURENDAR CHAUDHRY Other 23 Bareji 142963744 SHARDA DEVI GAURI SHANKAR SINGH Other 24 Bareji 142963914 SHOBHA DEVI JITENDAR Other 25 Bareji 142123285 ZERA DEVI MOHAN CHOUDHRY Other 26 Bareji 142963804 नीलम देवी रमेश सिंह Other हठसलाल 27 Bareji 142963783 शानॠति देवी Other कॠशवाहा 28 Bhataura Khurd 139729100 ANITA DEVI AMIT KUMAR Other 29 Bhataura Khurd 139303924 ARTI DEVI LATE PARMESWAR GUPTA Other 30 Bhataura Khurd 139730006 ASHA DEVI RAMDHIRAJ Other 31 Bhataura Khurd 139729385 BIBHA TARKESWAR Other S.N. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2012 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2012 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles: Cardboard Player Vasant Desai, Bollywood Mine, Ravi Shankar 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10000 Overseas US $ 1000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year, pay the full membership fee and get a digital copy of ‘The Record News’ published in that year. Life members are entitled to receive all the back issues on two data DVD’s. -

*** Details of State Bus Transport to Reach the Venue

भारत सरकार Government of India परमाणु ऊजा वभाग Department of Atomic Energy नाभकय इंधन सिम Nuclear Fuel Complex भत Recruitment – I ECIL Post Hyderabad – 500 062 . Ref: NFC/PAR-I/14/04/2017/1052 August 28, 2018 Subject: Schedule of Level-I Examination for the post of Upper Division Clerk advertised against Advt. No. NFC/01/2018 – Reg. *** With reference to applications submitted by the candidates for the post of Upper Division Clerk, post code 11808 against Advt. No. NFC/01/2018, Level-I examination (OMR – based) as detailed in the advertisement is scheduled as under: Date: 16.09.2018 (Sunday) Time: 10:00 Hrs., to 11:30 Hrs. Venue: Respective centres as per the Roll Numbers given below: Roll No. S. No. Venue of examination From To CMR College of Engineering and Technology - 01. 1180800001 1180801200 (CMRCET), Kandlakoya (V), Medchal Road, Hyderabad – 501 401. CMR Institute of Technology – (CMRIT), Kandlakoya 02. 1180801201 1180802234 (V), Medchal Road, Hyderabad – 501 401. CMR Engineering College – (CMREC) , Kandlakoya (V), 03. 1180802235 1180803266 Medchal Road, Hyderabad – 501 401. CMR Technical Campus – (CMRTC), Kandlakoya (V), 04. 1180803267 1180804298 Medchal Road, Hyderabad – 501 401. Atomic Energy Central School – II, DAE Colony, ECIL X 05. 1180804299 1180804434 Roads, Hyderabad – 500 062. List of candidates called for the Level-I examination for the post of UDC is attached to this letter. Candidates are required to download Admit Card for attending the examination from website www.nfcrecruitment.aptonline.in . Candidates who have submitted multiple applications have been allotted only one Roll Number and details of the applications are mentioned in respective admit card.