1998 Ravi Shankar Event Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Court for the State of Telangana

COURT NO. 13 THE HONOURABLE SRI JUSTICE CHALLA KODANDA RAM To be Heard on Tuesday The 20th day of July 2021( AT 10:30 AM - VIRTUAL MODE ) (MOTION LIST) SNO CASE PETITIONER ADV. RESPONDENT ADV. DISTRICT FOR ADMISSION 1 CRP/1064/2021 U SHANTHI BHUSHAN RAO KARIMNAGAR IA 1/2021 2 CRP/1068/2021 M JANARDHAN RAO RANGA REDDY IA 1/2021 3 CRP/1069/2021 M JANARDHAN RAO KARIMNAGAR IA 1/2021 4 CRP/1070/2021 M JANARDHAN RAO KARIMNAGAR IA 1/2021 5 SA/130/2021 N ASHOK KUMAR NALGONDA IA 1/2021 6 TRCMP/124/2021 J SRI RAMA KRISHNA MAHABUBNAGAR INTERLOCUTORY 7 AS/161/2021 SHAIK MADAR KHAMMAM IA 1/2021 8 CCCA/63/2021 VEDULA CHITRALEKHA HYDERABAD IA 1/2021 D MADHAVA RAO R-1-DIED VIDE C.T.(PER LRS OF RR-2 TO 5) CAVEAT FILED BY M/S D.MADHAVA RAO(2620)FOR R-3 9 CCCA/64/2021 VEDULA CHITRALEKHA HYDERABAD IA 1/2021 D MADHAVA RAO R-1-DIED VIDE C.T.(PER LRS OF RR-2 TO 5) CAVEAT FILED BY M/S D.MADHAVA RAO(2620)FOR R-3 1 COURT NO. 13 THE HONOURABLE SRI JUSTICE CHALLA KODANDA RAM To be Heard on Tuesday The 20th day of July 2021( AFTER MOTION LIST - VIRTUAL MODE ) (DAILY LIST) SNO CASE PETITIONER ADV. RESPONDENT ADV. DISTRICT PART-HEARD 10 SA/173/2015 J V S H SASTRY SRINIVAS BOBBILI RANGA REDDY IA 3/2015(SAMP 2200/2015) C SUBBA RAO RAVI SHANKAR JANDHYALA IA 1/2016(SAMP 216/2016) S V RAMANA (P) Proof of payment Memo filed By Appellants Vide Usr No.4864 Dt 30/01/2021 ( HEARD-IN-PART ) INFRUCTUOUS MATTERS 11 CMA/971/2013 M SRIKANTH REDDY A TULSI RAJ GOKUL HYDERABAD IA 1/2015(CMAMP 541/2015) RR 1TO3 APP CRP/4686/2013 RR 4&7 UNSERVED RR 5,6&8 SERVED 12 CRP/4686/2013 A TULSI RAJ GOKUL M SRIKANTH REDDY HYDERABAD IA 1/2013(CRPMP 6376/2013) FOR JUDGMENT 13 CCCA/106/2006 THE ADVOCATE GENERAL (TG) A RAVINDER REDDY HYDERABAD IA 5/2006(CCCAMP S DWARAKANATH 6360/2006) ::Sri Raj Kumar Rudra,SC for TSHWCS for IA 1/2018 Appellant IA 1/2019 FOR APPEARANCE 14 CC/187/2021 KONDAPARTHY KIRAN KUMAR A P SURESH RAM NALGONDA RR 1TO 20 NOTICE SERVED. -

Saregama India Limited Music | Films | Web Series | Tv Serials

SAREGAMA INDIA LIMITED MUSIC | FILMS | WEB SERIES | TV SERIALS ANNUAL REPORT 2020-21 B O A R D O F D I R E C T O R S Dr. Sanjiv Goenka Mr. Santanu Bhattacharya (DIN: 00074796) (DIN: 01794958) Chairman (Non-Executive) Non-Executive Independent Director Mrs. Preeti Goenka Mr. Arindam Sarkar (DIN: 05199069) (DIN: 06938957) Non-Executive Director Non-Executive Independent Director Mrs. Avarna Jain Mr. Noshir Naval Framjee (DIN: 02106305) (DIN: 01646640) Non-Executive Director Non-Executive Independent Director Mr. Vikram Mehra Mr. Umang Kanoria (DIN: 03556680) (DIN: 00081108) Managing Director Non-Executive Independent Director Ms. Suhana Murshed Ms. Kusum Dadoo (DIN: 08572394) (DIN: 06967827) Non-Executive Independent Director Non-Executive Independent Director (w.e.f March 23, 2021) (period June 5, 2020 - Feb 4, 2021) Registered Office - Kolkata Chief Financial Officer - Mr. Vineet Garg 33, Jessore Road, Dum Dum, Kolkata - 700028, West Bengal. Company Secretary - Ms. Kamana Goenka Phone: (033) 2551 2984, 2551 4773 e-mail: [email protected] Bankers CIN : L22213WB1946PLC014346 Punjab National Bank (erstwhile United Bank of India) Website : www.saregama.com State Bank of India ICICI Bank Limited Head Office - Mumbai 2nd Floor, Spencer Building, 30, Forjett Street, Statutory Auditor Grant Road (W), Mumbai – 400 036 BSR and Co. LLP, Chartered Accountants Phone: (022) 6688 6200 (ICAI Firm Registration Number - 101248W/W-100022) Regional Offices Internal Auditor Ernst and Young LLP Delhi Secretarial Auditor A-62, 1st Floor, FIEE Complex, Okhla Industrial Area, MR & Associates Phase – II, New Delhi – 110 020 Phone: (011) 4051 9759 Cost Auditor Shome and Banerjee Chennai rd Door No. -

IME Annual Report 2020-2021 Low Size

Supported by Annual Report 2020-2021 Only in the darkness can “ you see the stars. ― Martin Luther King “ Namaste We have collectively endured one of the defining experiences of our life and times. What started off as a pause in the hustle and bustle of daily life has now become a happening that will forever define the way we see the world. Many of us experienced loss – of loved ones, of time, of precious moments, and of a sense of normalcy. There were days when I questioned everything, and felt the meaninglessness of it all. At the same time, I realized that the future is built one day at a time, by the seemingly small actions we take each day; that, as Martin Luther King said, everything that is done in the world is done by hope. And so, we see ourselves looking back at a most strange year, but one that I am glad to report has been extremely productive for the Indian Music Experience Museum, in our mission to build community through music. The team at IME seamlessly adapted to the online world. We ensured the continuity of music education at the Learning Centre. We unveiled two new online exhibits through an important partnership with Google Art and Culture. Our work in preserving musical traditions achieved an important milestone through the creation of an online archive on the life and works of legendary violinist and composer, Mysore T. Chowdiah, in collaboration with the Shankar Mahadevan Academy. We presented a wide variety of talks, discussions, workshops, showcases, and exhibit walkthroughs online, growing our audience beyond the geographic limitations of in-person events. -

Assets.Kpmg › Content › Dam › Kpmg › Pdf › 2012 › 05 › Report-2012.Pdf

Digitization of theatr Digital DawnSmar Tablets tphones Online applications The metamorphosis kingSmar Mobile payments or tphones Digital monetizationbegins Smartphones Digital cable FICCI-KPMG es Indian MeNicdia anhed E nconttertainmentent Tablets Social netw Mobile advertisingTablets HighIndus tdefinitionry Report 2012 E-books Tablets Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities 3D exhibition Digital cable Portals Home Video Pay TV Portals Online applications Social networkingDigitization of theatres Vernacular content Mobile advertising Mobile payments Console gaming Viral Digitization of theatres Tablets Mobile gaming marketing Growing sequels Digital cable Social networking Niche content Digital Rights Management Digital cable Regionalisation Advergaming DTH Mobile gamingSmartphones High definition Advergaming Mobile payments 3D exhibition Digital cable Smartphones Tablets Home Video Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Vernacular content Portals Mobile advertising Social networking Mobile advertising Social networking Tablets Digital cable Online applicationsDTH Tablets Growing sequels Micropayment Pay TV Niche content Portals Mobile payments Digital cable Console gaming Digital monetization DigitizationDTH Mobile gaming Smartphones E-books Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Mobile advertising Mobile gaming Pay TV Digitization of theatres Mobile gamingDTHConsole gaming E-books Mobile advertising RegionalisationTablets Online applications Digital cable E-books Regionalisation Home Video Console gaming Pay TVOnline applications -

Indian EXPRESS TRI-STATE Newsline NOVEMBER 16, 2012 L

20 The Indian EXPRESS TRI-STATE Newsline NOVEMBER 16, 2012 L. Subrmaniam, Kavitha to perform in NY on Dec 9 PRAKASH M SWAMY New York Philharmonic Orchestra in London, The Kennedy Center in and Zubin Mehta’s Fantasy of Ve- Washington DC, The Lincoln Center NEW YORK dic Chants, the Swiss Romande Or- in New York, Madison Square Gar- chestra Turbulence, the Kirov Ballet den, Zhongshan Music hall in Bei- nternationally renowned violin Shanti Priya, the Oslo Philharmonic jing, The Esplanade in Singapore, etc. maestro Padma Bhushan Dr. Orchestra the Concerto for Two Vio- Few of her famous songs are IL. Subramaniam and his wife lins, the Berlin Opera Global Sym- from movies 1942: A love Story, Mr Kavita Krishnamurti Subramaniam, phony. His compositions have been India, Bombay, Hum dil de chuke an accomplished Bollywood play- used in various stage presentations sanam, Dil Chahta Hai, Kabhi back and Hindustani classical music including San Jose Ballet Company Khushi Kabhi Gam. singer, will present a grand concert and Alvin Ailey Company. The event will be held at NYU for South Asian Music and Arts As- Kavita Krishnamurti Subrama- Skirball auditorium in Washington sociation on Dec 9 in New York City. niam is a famous playback singer, Square in New York. India’s violin icon is a child trained in Hindustani classical music According to Simmi Bhatia, prodigy and was given the title Vio- and a winner of Padmashri award. executive director SAMAA (South lin Chakravarthy (emperor of the A versatile singer who has sung with Asian Music and Arts Association) is violin), Grammy nominated, win- Indian classical maestros like Pandit a non-profit organization dedicated ner Dr Subramaniam has scored Jasraj and BalaMurali Krishna, while to promoting quality music and arts for films like Salaam Bombay and also worked with music composers from South Asia through live perfor- Mississippi Masala, featured soloist like R. -

Smt. Kala Ramnath Concert

presents in association with UC Worldfest 2009 ART at its best Internationally Renowned Hindustani Violinis Smt. Kala Ramnath accompanied by Shri Prithwiraj Bhattacharjee on Tabla Date: 25 th April, 2009 (Saturday) Venue: 4400 Aronoff (DAAP Auditorium) Time: 6 :00 pm Parking: Langsam Garage Artiste Biography Maestro KALA RAMNATH , the contemporary torch bearer of the Mewati Gharana, stands today Prithwiraj Bhattacharjee another young and amongst the most outstanding instrumental musicians in the North Indian classical genre. Born upcoming artist began his initial training under into a family of prodigious musical talent, which his guru Dhiranjan Chakraborty at the tender has given Indian music such violin legends as Prof. age of seven. In the year 1994 his life long T.N. Krishnan and Dr. N. Rajam, Kala's genius with the violin manifested itself from childhood. She ambition of learning under the tabla maestro began playing the violin at the tender age of three Ustad Alla Rakha and Ustad Zakir Hussain came under the strict tutelage of her grandfather true. Blessed with highly cultivated fingers, Vidwan. Narayan Aiyar. Simultaneously she received training from her aunt Dr. Smt. N. Rajam. absorbing all the aspects of his guru’s style For fifteen years she put herself under the training through vigorous riyaz under the ever watchful of Mewati vocal maestro, Sangeet Martand Pandit eyes of his guru have made him progress into a Jasraj. This has brought a rare vocal emotionalism to her art. Kala's violin playing is characterized by very promising upcoming tabla player. Prithwi an immaculate bowing and fingering technique, has performed in many solo concerts and command over all aspects of laya, richness and travelled extensively all over India and abroad clarity in sur. -

Sukanya an Opera by Ravi Shankar

Sukanya an opera by Ravi Shankar Royal Opera House London Philharmonic Orchestra BBC Singers Ravi Shankar was one of the most influential musicians of all time. He inspired people from all walks of life and musicians from all genres of music. These included legendary names such as George Harrison, Yehudi Menuhin, John Coltrane and Philip Glass. Ravi Shankar’s music rapidly spread throughout the world, crossing all cultural and generational boundaries. Ravi Shankar envisaged Sukanya as a truly ground-breaking piece of musical theatre which will explore the common ground between the music, dance and theatrical traditions of India and the West. Ravi Shankar was in a unique position to visualise the common ground between East and West. He was steeped in the ancient musical and dramatic traditions of India through his guru Baba Allaudhin Khan and he also gained a deep knowledge of the music and drama of the west from a very young age. And yet he lived in an age where jet travel, radio, television and recorded music opened up the world and introduced him to musicians from across the globe that he could share and learn music with. As a young man Shankar experienced the reaction of Westerners to hearing Indian music for the first time: although many found it exciting he realised that it needed to be presented very carefully for the untrained Western ear to realise its depths. Thus, Ravi Shankar became the first Indian musician to explain these concepts to his audiences. Shankar had a vision for Sukanya that would break the mould of traditional opera: a truly ground-breaking work which will explore the common ground between the music, dance and theatrical traditions of India and the West. -

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

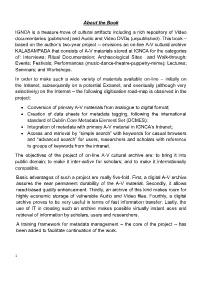

(Dr) Utpal K Banerjee

About the Book IGNCA is a treasure-trove of cultural artifacts including a rich repository of Video documentaries (published) and Audio and Video DVDs (unpublished). This book – based on the author’s two-year project -- envisions an on-line A-V cultural archive KALASAMPADA that consists of A-V materials stored at IGNCA for the categories of: Interviews; Ritual Documentation; Archaeological Sites and Walk-through; Events; Festivals; Performances (music-dance-theatre-puppetry-mime); Lectures; Seminars; and Workshops. In order to make such a wide variety of materials available on-line – initially on the Intranet, subsequently on a potential Extranet, and eventually (although very selectively) on the Internet – the following digitisation road-map is observed in the project: Conversion of primary A-V materials from analogue to digital format; Creation of data sheets for metadata tagging, following the international standard of Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (DCMES); Integration of metadata with primary A-V material in IGNCA’s Intranet; Access and retrieval by “simple search” with keywords for casual browsers and “advanced search” for users, researchers and scholars with reference to groups of keywords from the intranet. The objectives of the project of on-line A-V cultural archive are: to bring it into public domain; to make it inter-active for scholars; and to make it internationally compatible. Basic advantages of such a project are really five-fold. First, a digital A-V archive assures the near permanent durability of the A-V material. Secondly, it allows need-based quality enhancement. Thirdly, an archive of this kind makes room for highly economic storage of vulnerable Audio and Video files. -

9312 India Power 2.1.Indd

INDIA: A RISING POWER Dr V Nilakant, Associate Professor Department of Management University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand July 2006 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 02 INDIA: A PROFILE 04 GEOGRAPHY 04 PEOPLE 04 CULTURE AND HISTORY 05 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 07 HISTORY AND GROWTH 07 INDIAN ECONOMY 08 INDIA AS A REGIONAL POWER 11 INDIA: CHALLENGES AHEAD 16 INDIA: OPPORTUNITIES 18 CONCLUSION 20 APPENDIX 1: BRIEF PROFILE OF INDIA 21 ISBN-13: 978-0-473-11412-1 ISBN-10: 0-473-11412-7 INDIA: A RISING POWER Dr V Nilakant “From a distance, India often appears as a kaleidoscope of competing, perhaps superficial, images. Is it atomic weapons, or ahimsa? A land struggling against poverty and inequality, or the world’s largest middle-class society? Is it still simmering with communal tensions, or history’s most successful melting pot? Is it Bollywood or Satyajit Ray? Swetta Chetty or Alla Rakha? Is it the handloom or the hyperlink?” US President Bill Clinton in an address to the joint session of the Indian Parliament New Delhi, India, 22 March 2000 INDIA: A RISING POWER 01 INTRODUCTION IN LATE MAY 2005, the President of India, A P J Abdul Kalam, was on a state visit to Switzerland. Reportedly, he surprised his Swiss counterpart, Samuel Schmid, by offering him a gift. In itself this was not an unusual incident. It is, after all, expected from the head of state of a developing country like India to bear traditional gifts that reflect its rich and ancient civilization. What made this incident unusual was the nature of the gift. -

WGLT Program Guide, October, 1987

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData WGLT Program Guides Arts and Sciences Fall 10-1-1987 WGLT Program Guide, October, 1987 Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg Recommended Citation Illinois State University, "WGLT Program Guide, October, 1987" (1987). WGLT Program Guides. 69. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg/69 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in WGLT Program Guides by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WGLT fm89 OCTOBER 1987 PROGRAM GUIDE Public Radio from !SU Keith and Betty thought good quality stereo equipment and good quality music made a perfect combination, and so became interested in . underwriting on WGLT. "We felt the WGLT listeners would be very audio BE conscious," Betty said. UNDERWRITER Consequently, the listeners on WGLT are very similar A to the target customers of PROFILE: Curtis Mathes. MEMBER Keith and Betty feel CURTIS public radio is an important Show your support of part of the community and your public radio station MATHES provides a service the SEND and send in your pledge community wants. today! I According to Betty, "Public OF radio brings culture to the YOUR community without the BLOOMINGTON community having to ow that TENDER his month we search for it." summer has feature Curtis The idea of quality radio ended and Mathes of is very similar to Keith and winter is Bloomington Betty's business philosophy. -

An Evening of Indian Classical Music

INTERNATIONAL CENTRE GOA Organises An Evening of Indian Classical Music For the Faculty and Students of College of William & Mary, USA Sunday, 8 June 2008 at 6:30 – 8:00 pm Venue: MANDOVI Hall, The International Centre, Goa, Dona Paula, Goa 403004 PROGRAMME Welcome by M Rajaretnam, Director/ Chief Executive, International Centre Goa Introduction of the Jugalbandi Dr. Anupam Sarkar and artists by Jugalbandi of Sitar by Shri Manab Das, and Flute by Shri Sonik Arvind Velingkar Accompanied on Tabla by Shri Ulhas Velingkar Compere: Ms. Soma Bhattacharya ------------------------------------------- A jugalbandi (also spelled jugalbandhi ) is a performance, in Indian classical music, featuring two solo musicians. The word jugalbandhi means, literally, “Entwined twins”. Often, the musicians will play different instruments, as for example the famous duets between sitarist Ravi Shankar and sarod player Ali Akbar Khan, who popularized the format with their performances of the 1970s. More rarely, the musicians (either vocalists or instrumentalists) may be from different traditions (i.e. Carnatic music and Hindustani classical music). What defines jugalbandhi is that the two soloists be on an equal footing. While any Indian music performance may feature two musicians, a performance can only be deemed a jugalbandhi if neither is clearly the soloist and neither clearly an accompanist. In jugalbandhi , both musicians act as lead players, and a playful competition often ensues between the two performers. ABOUT ARTISTS Shri Manab Das: Eminent Sitarist Manab Das, Masters in Music from Visva Bharati University. He started his career at the age of six under the tutelage of Late Ustad Ali Ahmed Kahn and later under the guidance of Pandit Indranil Bhattacharya in the age old tradition of Guru Shishya Parampara.