1481186712P4M12TEXT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rabindra Sangeet

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION NET BUREAU Subject: MUSIC Code No.: 16 SYLLABUS Hindustani (Vocal, Instrumental & Musicology), Karnataka, Percussion and Rabindra Sangeet Note:- Unit-I, II, III & IV are common to all in music Unit-V to X are subject specific in music www.careerindia.com -1- Unit-I Technical Terms: Sangeet, Nada: ahata & anahata , Shruti & its five jaties, Seven Vedic Swaras, Seven Swaras used in Gandharva, Suddha & Vikrit Swara, Vadi- Samvadi, Anuvadi-Vivadi, Saptak, Aroha, Avaroha, Pakad / vishesa sanchara, Purvanga, Uttaranga, Audava, Shadava, Sampoorna, Varna, Alankara, Alapa, Tana, Gamaka, Alpatva-Bahutva, Graha, Ansha, Nyasa, Apanyas, Avirbhav,Tirobhava, Geeta; Gandharva, Gana, Marga Sangeeta, Deshi Sangeeta, Kutapa, Vrinda, Vaggeyakara Mela, Thata, Raga, Upanga ,Bhashanga ,Meend, Khatka, Murki, Soot, Gat, Jod, Jhala, Ghaseet, Baj, Harmony and Melody, Tala, laya and different layakari, common talas in Hindustani music, Sapta Talas and 35 Talas, Taladasa pranas, Yati, Theka, Matra, Vibhag, Tali, Khali, Quida, Peshkar, Uthaan, Gat, Paran, Rela, Tihai, Chakradar, Laggi, Ladi, Marga-Deshi Tala, Avartana, Sama, Vishama, Atita, Anagata, Dasvidha Gamakas, Panchdasa Gamakas ,Katapayadi scheme, Names of 12 Chakras, Twelve Swarasthanas, Niraval, Sangati, Mudra, Shadangas , Alapana, Tanam, Kaku, Akarmatrik notations. Unit-II Folk Music Origin, evolution and classification of Indian folk song / music. Characteristics of folk music. Detailed study of folk music, folk instruments and performers of various regions in India. Ragas and Talas used in folk music Folk fairs & festivals in India. www.careerindia.com -2- Unit-III Rasa and Aesthetics: Rasa, Principles of Rasa according to Bharata and others. Rasa nishpatti and its application to Indian Classical Music. Bhava and Rasa Rasa in relation to swara, laya, tala, chhanda and lyrics. -

SPECIAL REPORT an Analysis of the June 1-15, 2008 the Fortnightly from Afaqs! Mobile Marketing Business in India 16

Rs 40 THE SPECIAL REPORT An analysis of the June 1-15, 2008 The fortnightly from afaqs! mobile marketing business in India 16 PROFILE Mohit Anand Making the transition from software to Channel [V]. 22 SPRITE Being Upfront How a consistent message worked like magic. 24 DEFINING MOMENTS Gullu Sen Anything can change your life, feels this adman. TV SHOWS The Power of Stars 12 WEBSITES Are details really everything? A report At Home 14 on whether execution in Indian PARLE MONACO advertising matches the idea. The Lighter Side 38 28 STAR COMIC BOOKS Animated in Print 38 The fortnightly from agencyfaqs! This fortnight... Volume III, Issue 21 he subject of this issue’s cover story has been provoked by the impending Cannes festival EDITOR T– but is not really about it. In the course of covering international awards, we have found Sreekant Khandekar that the quality of execution in Indian advertising keeps cropping up. The issue generally gets sidelined because the natural focus is the idea behind a campaign. PUBLISHER Prasanna Singh Craft and execution are not a pre-requisite for awards alone. It is the stuff of everyday advertising life, the very thing that can enhance the impact of an idea dramatically – EXECUTIVE EDITOR or wreck it, quite as easily. Happydent, Fevicol and Nike are three examples of the M Venkatesh delightful consequence when great idea meets great execution. CREATIVE CONSULTANTS We talk to creative directors, film makers and to clients to find out what the prob- PealiDezine lem is when it comes to execution. Is it about time? Money? Or simply about an LAYOUT Indian way of doing things? You may not like all that you read but it will make you Vinay Dominic look at an old issue afresh. -

Reconstructing the Indian Filmography

ASHISH RAJADHYAKSHA Reconstructing The Indian Filmography Sitara Devi and the Indian filmographer A n apocryphal story has V.A.K. Ranga Rao, the irascible collector of music and authority on South Indian cinema, offering an open challenge. It seems he saw Mother India on his television one night and was taken aback to see Sitara Devi’s name in the acting credits. The open challenge was to anyone who could spot Sitara Devi anywhere in the film. And, he asked, if she was not in the film, to answer two questions. First, what happened? Was something filmed with her and cut out? If so, when was this cut out? Almost more important: what to do with Sitara Devi’s filmography? Should Mother India feature in that or not? Such a problem would cut deep among what I want to call the classic years of the Indian filmographers. The Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema decided to include Sitara Devi’s name in its credits, mainly because its own key source for Hindi credits before 1970 was Firoze Rangoonwala’s iconic Indian Filmography, Silent and Hindi Film: 1897-1969, published in 1970 and Har Mandir Singh ‘Hamraaz’s somewhat different, equally legendary Hindi Film Geet Kosh which came out with the first edition of its 1951-60 listings in 1980. The Singh Geet Kosh tradition would provide bulwark support both on JOURNAL OF THE MOVING IMAGE 13 its own but also through a series of other Geet Koshes by Harish Raghuvanshi on Gujarati, Murladhar Soni on Rajasthani and many others. Like Ranga Rao, Singh and the other Geet Kosh editors have had his own variations of the Sitara Devi problem: his focus was on songs, and he was coming across major discrepancies between film titles, their publicity material and record listings. -

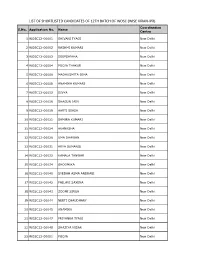

List of Shortlisted Candidates of 12Th Batch of Wosc (Wise Kiran-Ipr)

LIST OF SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES OF 12TH BATCH OF WOSC (WISE KIRAN-IPR) Coordination S.No. Application No. Name Centre 1WOSC12-00001 SHIVANI TYAGI New Delhi 2WOSC12-00002 RASHMI KUMARI New Delhi 3WOSC12-00003 DEEPSHIKHA New Delhi 4WOSC12-00004 POOJA THAKUR New Delhi 5WOSC12-00006 MADHUSMITA OJHA New Delhi 6WOSC12-00008 ANAMIKA KUMARI New Delhi 7WOSC12-00012 DIVYA New Delhi 8WOSC12-00016 SHAGUN JAIN New Delhi 9WOSC12-00019 AARTI SINGH New Delhi 10WOSC12-00021 SAMIRA KUMARI New Delhi 11WOSC12-00024 AKANKSHA New Delhi 12WOSC12-00026 UMA DHAWAN New Delhi 13WOSC12-00031 ARYA SUMANGI New Delhi 14WOSC12-00032 KAMALA TANWAR New Delhi 15WOSC12-00034 BHOOMIKA New Delhi 16WOSC12-00040 SYEDAH ASMA ANDRABI New Delhi 17WOSC12-00042 PALLAVI SAXENA New Delhi 18WOSC12-00043 ZOOMI SINGH New Delhi 19WOSC12-00044 NEETI CHAUDHARY New Delhi 20WOSC12-00045 ANAMIKA New Delhi 21WOSC12-00047 PRIYANKA TYAGI New Delhi 22WOSC12-00048 SHAZIYA NISAR New Delhi 23WOSC12-00051 POOJA New Delhi 24WOSC12-00053 NUSRAT PRAWEEN New Delhi 25WOSC12-00056 NADISH MANZOOR New Delhi 26WOSC12-00057 VIBHA BHATIA New Delhi 27WOSC12-00059 AMALA MASA New Delhi 28WOSC12-00062 NEHA SHARMA New Delhi 29WOSC12-00068 TARUNA SHARMA New Delhi 30WOSC12-00070 MEDHAVI New Delhi 31WOSC12-00074 VIJAY LAXMI New Delhi 32WOSC12-00075 RAKHI GAUNIYAL New Delhi 33WOSC12-00078 RASHMI GUPTA New Delhi 34WOSC12-00080 PREETI GUPTA New Delhi 35WOSC12-00083 MONIKA New Delhi 36WOSC12-00084 POONAM New Delhi 37WOSC12-00097 SUDHA CHINNU New Delhi 38WOSC12-00099 AZRA UNNISA New Delhi 39WOSC12-00100 RUCHI SINGHAL New -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

(Dr) Utpal K Banerjee

About the Book IGNCA is a treasure-trove of cultural artifacts including a rich repository of Video documentaries (published) and Audio and Video DVDs (unpublished). This book – based on the author’s two-year project -- envisions an on-line A-V cultural archive KALASAMPADA that consists of A-V materials stored at IGNCA for the categories of: Interviews; Ritual Documentation; Archaeological Sites and Walk-through; Events; Festivals; Performances (music-dance-theatre-puppetry-mime); Lectures; Seminars; and Workshops. In order to make such a wide variety of materials available on-line – initially on the Intranet, subsequently on a potential Extranet, and eventually (although very selectively) on the Internet – the following digitisation road-map is observed in the project: Conversion of primary A-V materials from analogue to digital format; Creation of data sheets for metadata tagging, following the international standard of Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (DCMES); Integration of metadata with primary A-V material in IGNCA’s Intranet; Access and retrieval by “simple search” with keywords for casual browsers and “advanced search” for users, researchers and scholars with reference to groups of keywords from the intranet. The objectives of the project of on-line A-V cultural archive are: to bring it into public domain; to make it inter-active for scholars; and to make it internationally compatible. Basic advantages of such a project are really five-fold. First, a digital A-V archive assures the near permanent durability of the A-V material. Secondly, it allows need-based quality enhancement. Thirdly, an archive of this kind makes room for highly economic storage of vulnerable Audio and Video files. -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

Times-NIE-Web-Ed-AUGUST 14-2021-Page3.Qxd

CELLULAR JAIL, ANDAMAN & BIRLA HOUSE: Birla House is a muse- NICOBAR ISLANDS: Also known as um dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi. It ‘Kala Pani’, the British used the is the location where Gandhi spent CELEBRATING FREEDOM jail to exile political prisoners at the last 144 days of his life and was SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 2021 03 this colonial prison assassinated on January 30, 1948 CLICK HERE: PAGE 3 AND 4 Pre-Independence slogans and its relevance in India today Slogans raised by leaders during the freedom movement set the mood of the nation’s revolution for its independence. They epitomised the struggle and hopes of millions of Indians. Author and former ad guru ANUJA CHAUHAN revisits these powerful slogans and explains their history and relevance in a contemporary India SATYAMEV JAYATE QUIT INDIA LIKE SWARAJ, KHADI IS (Truth alone triumphs) HISTORY: This slogan is widely associ- OUR BIRTH-RIGHT ated with Mahatma Gandhi (what he HISTORY: Inscribed at the base of started was the Quit India Movement India’s national emblem, this phrase is from August 8, 1942, in Bombay (then), a mantra from the ancient Indian scr- but the term ‘Quit India’ was actually ipture, ‘Mundaka Upanishad’, which coined by a lesser-known hero of was popularised by freedom fighter India’s freedom struggle – Yusuf Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya during Meherally. He had published a booklet India’s freedom movement. titled ‘Quit India’ (sold in weeks) and got over a thousand ‘Quit India’ badges to give life to the slogan that Gandhi also started using and popularised. ‘YOUNGSTERS, DON’T QUIT INDIA’: Quit India was a powerful slogan and HISTORY: Mahatma Gandhi’s call to as a slogan) was written by Urdu the jingle of an epic movement meant use khadi became a movement for poet Muhammad Iqbal in 1904 for to drive the British away from our the indigenous swadeshi (Indian) children. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration.