Spencer and Gillen's Collaborative Fieldwork in Central Australia and Its Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 4

NASA/TP—2001–209990 Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 04 F. Espenak and J. Anderson Central Lat,Lng = -28.0 132.0 P Factor = 0.46 Semi W,H = 0.35 0.28 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:40:42 AM High Res World Data [WPD1] WorldMap v2.00, F. Espenak Orthographic Projection Scale = 8.00 mm/° = 1:13915000 Central Lat,Lng = -10.0 26.0 P Factor = 0.31 Semi W,H = 0.70 0.50 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:17:57 AM September 2001 The NASA STI Program Office … in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical science. The NASA Scientific and Technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other Information (STI) Program Office plays a key meetings sponsored or cosponsored by NASA. part in helping NASA maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, techni- cal, or historical information from NASA The NASA STI Program Office is operated by programs, projects, and mission, often con- Langley Research Center, the lead center for cerned with subjects having substantial public NASA’s scientific and technical information. The interest. NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. aeronautical and space science STI in the world. English-language translations of foreign scien- The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional tific and technical material pertinent to NASA’s mechanism for disseminating the results of its mission. -

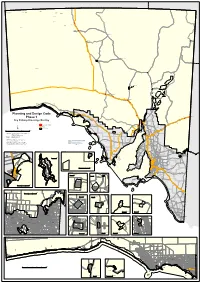

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

To View More Samplers Click Here

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently South Australian Government Gazette 1888 Ref. AU5100-1888 ISBN: 978 1 74222 084 0 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by Flinders University www.lib.flinders.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

Spencer Box 1 a Horn

Pitt Rivers Museum ms collections Spencer papers Box 1 A Horn correspondence Horn Letter 1 [The Adelaide Club] 17 Ap/ 94 Dear Mr. Spencer I am gradually getting things focussed here and think we can get a start on the 3d May [1] re photography I am having a small dark tent made one that can be suspended from the branch of a tree like a huge extinguisher about 4 ft in diameter I am going to take a 1/2 plate Camera with rapid rectilinear lens, and glass plates. You need not bring any rapid plates for your whole plate Camera as in the bright light up there one can get splendid instantaneous results with the Ordinary plate. Please make your Collecting plant as light as is consistent with efficiency as everything has to be carried on camels. Have you ever tried the “Tondeur” developer it is splendid for travelling as it is a one mixture solution and I find gives good results when used even a dozen times, it is a mixture of Hydrogen “Ersine” & can be had at Baker & Rouse’s I told Stirling [2] to write you to engage Keartland [3] Believe me Sincerely yrs WA Horn [4] Horn Letter 2 [The Adelaide Club] 9 June / 94 My dear Spencer, The photos of Ayers Chambers Pillar turned out fairly but a little light fogged & over exposed I got a very good one of a Tempe Downs blackfellow in the act of throwing a spear and another throwing a boomerang. if Gillen [5] has any really good [sic] you might try and get the negatives – When you are turning through the Gibber country get Harry [6] to shew you the hoards made by the ants they really seem to have moved stones by a pound in weight in order to get a clear track— I had a very rough trip by the mail it is really something to remember especially over the Gibbers and the dust was awful I hope you will be able to get Ayers rock as it would be a great addition to the book Sincerely thine [?] W A Horn Horn Letter 3 New University Club St James St. -

Journal of J. G. Macdonald on an Expedition from Port Denison to The

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Pest Management Community Activities Volunteer Support Water

The SA Arid Lands NRM Board is responsible for overseeing Best practice soil conservation and grading workshop the management of natural resources over more than half of NAIDOC events at Ikara-Flinders Ranges South Australia – an area greater than 500,000 square Supported people from the SA Arid Lands Region to kilometres. This means its annual income of about $5million - attend training and development events including: Beef generated from a number of sources including grants and Week 2018; PIRSA - Stepping into Leadership program; levies - amounts to less than $10 per square kilometre. 2018 Thriving Women’s Conference; 2017 Australian Rangelands Society Conference; and SA Weeds To help the Board meet its responsibilities, a land-based Conference NRM levy and a NRM water levy are collected annually, Partnership with SheepConnect Pastoral for grazing providing critical leverage for the Board to obtain funding nutrition and reproductive efficiency workshops at Yunta from government and industry. In 2017/18 the Board’s and Hawker, as well as online webinars combined funding has contributed to the following activities: Volunteer support Pest management Support for Blinman Parachilna Pest Plant Control Group Wild dog management – trapper training, bi-annual bait volunteers who poisoned or removed more than 6000 injection service, subsidised baits and trapper cacti and contributed 3000 volunteer hours in 2017/18. reimbursement Sponsorship of the Great Tracks Clean Up Crew who, in Feral pig management workshop in North East Pastoral 2017/18, retrieved 63 tonnes of rubbish, 548 tyres and Expanded cat baiting trial onto privately owned land to travelled more than 2200km across the region. -

Beltana State Heritage Area: Guidelines, DEW Technical Report 2018/, Government of South Australia, Through Department for Environment and Water, Adelaide

Department for Environment and Water GPO Box 1047, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone +61 (08) 8204 1910 Website www.environment.sa.gov.au Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia License www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au Copyright Owner: Crown in right of the state of South Australia 2018 © Government of South Australia 2018 Disclaimer While every reasonable effort has been made to verify the information in this fact sheet use of the information contained is at your sole risk. The Department recommends that you independently verify the information before taking any action. ISBN 978-1-921800-84-09 Preferred way to cite this publication Heritage South Australia, 2018, Beltana State heritage area: guidelines, DEW Technical report 2018/, Government of South Australia, through Department for Environment and Water, Adelaide Download this document at: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au Beltana State Heritage Area - DEW # 13886 SHA declared in 1987 The information in these Guidelines is advisory, to assist you in understanding the policies and processes for development in the State Heritage Area. It is recommended that you seek professional advice or contact the relevant State Heritage Adviser at the Department for Environment and Water (DEW) regarding any specific enquiries or for further assistance concerning the use and development of land. Being properly prepared can save you time and money in the long run. Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Beltana State Heritage Area 1 1.2 Purpose of Guidelines 1 1.3 Getting Approval 1 1.4 Seeking Heritage Advice 1 2. History and Significance 3 2.1 History 3 2.2 Significance 3 2.3 Character and Setting 3 3. -

MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND SIMPSON DESERT CONSERVATION PARK Pastoral Station ALTON DOWNS MULKA PANDIE PANDIE Boundary CORDILLO DOWNS Conservation and National Parks Regional reserve/ SIMPSON DESERT Pastoral Station REGIONAL RESERVE Aboriginal Land Marree - Innamincka CLIFTON HILLS NRM Group COONGIE LAKES NATIONAL PARK INNAMINCKA REGIONAL RESERVE SA Arid Lands NRM Region Boundary INNAMINCKA Dog Fence COWARIE Major Road MACUMBA ! KALAMURINA Innamincka Minor Road / Track MUNGERANIE Railway GIDGEALPA ! Moomba Cadastral Boundary THE PEAKE Watercourse LAKE EYRE (NORTH) LAKE EYRE MULKA Mainly Dry Lake NATIONAL PARK MERTY MERTY STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION RESERVE PARK ETADUNNA BOLLARDS ANNA CREEK LAGOON DULKANINNA MULOORINA LINDON LAKE BLANCHE LAKE EYRE (SOUTH) MULOORINA CLAYTON MURNPEOWIE Produced by: Resource Information, Department of Water, Curdimurka ! STRZELECKI Land and Biodiversity Conservation. REGIONAL Data source: Pastoral lease names and boundaries supplied by FINNISS MARREE RESERVE Pastoral Program, DWLBC. Cadastre and Reserves SPRINGS LAKE supplied by the Department for Environment and CALLANNA ABORIGINAL ! Marree CALLABONNA Heritage. Waterbodies, Roads and Place names LAND FOSSIL supplied by Geoscience Australia. STUARTS CREEK MUNDOWDNA Projection: MGA Zone 53. RESERVE Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia, 1994. MOOLAWATANA MOUNT MOUNT LYNDHURST FREELING FARINA MULGARIA WITCHELINA UMBERATANA ARKAROOLA WALES SOUTH NEW -

Index to Volume 3A (1892-1895) University of Adelaide Archives: Series 163 University Newscuttings Books

Index to Volume 3a (1892-1895) University of Adelaide Archives: Series 163 University Newscuttings Books A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A Adelaide Hospital, non-admission of lecturer Dr Lendon to the hospital, 87 Adelaide University Union, meeting to establish union, 107 Allen, James Bernard, awarded 1851 Exhibition Science Scholarship, 3 Angas Engineering Scholarship, winners, 30, 63, 106, 107, 108 annual report, 26-27, 28, 56-57, 58, 103, 104, 105 Ash, George, awarded Stow Prize, 10, 11, 12, 13, 47 B Beare, Thomas Hudson, to represent University at tercentenary of Dublin University, 1 Belt, F W South Australian member of Horn Expedition, 73, 76 Bensley, Professor Edward, appointed Hughes Professor of Classics, 107 promotes and gives extension lectures, 110, 111, 115, 116, 117, 119, 120, 121 Boas, Rev A T, to offer classes in Hebrew and Chaldaic languages, 88, 89, 106 Bonnin, James Atkinson, awarded Elder Prize, 8 Boulger, Professor Edward Vaughan, gives address at commemoration, 52-53, 53-54 arguments for studying Greek, 51-52 appointed Professor of Classics, 71 suffers illness, 88 C calendar, 26-27, 28, 56-57, 58, 103, 104, 105 Cavanagh-Mainwaring, Wentworth R, awarded Everard Scholaship, 8, 10, 11 ceremonies and celebrations, annual university ball, 85, Chapple, Frederic, Headmaster of Prince Alfred College is Warden of Senate, 20 Chapple, Marian, John Howard Clark Scholar, 51, 52, 53 Chemistry, study of, pharmacy apprentices to study chemistry at University, 40, 41a, 41b Clark, Edward Vincent, awarded Angas -

Olympic Dam Expansion

OLYMPIC DAM EXPANSION DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT 2009 APPENDIX P CULTURAL HERITAGE ISBN 978-0-9806218-0-8 (set) ISBN 978-0-9806218-4-6 (appendices) APPENDIX P CULTURAL HERITAGE APPENDIX P1 Aboriginal cultural heritage Table P1 Aboriginal Cultural Heritage reports held by BHP Billiton AUTHOR DATE TITLE Antakirinja Incorporated Undated – circa Report to Roxby Management Services by Antakirinja Incorporated on August 1985 Matters Related To Aboriginal Interests in The Project Area at Olympic Dam Anthropos Australis February 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Ethnographic Field Survey of Proposed Works at Olympic Dam Operations, Roxby Downs, South Australia Anthropos Australis April 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Archaeological Field Survey of Proposed Works at Olympic Dam Operations, Roxby Downs, South Australia Anthropos Australis May 1996 Final Preliminary Advice on an Archaeological Survey of Roxby Downs Town, Eastern and Southern Subdivision, for Olympic Dam Operations, Western Mining Corporation Limited, South Australia Archae-Aus Pty Ltd July 1996 The Report of an Archaeological Field Inspection of Proposed Works Areas within Olympic Dam Operations’ Mining Lease, Roxby Downs, South Australia Archae-Aus Pty Ltd October 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Heritage Assessment of Proposed Works Areas at Olympic Dam Operations’ Mining Lease and Village Site, Roxby Downs, South Australia (Volumes 1-2) Archae-Aus Pty Ltd April 1997 A Report of the Detailed Re-Recording of Selected Archaeological Sites within the Olympic Dam Special -

Hermannsburg Historic Precinct

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Indigenous Item: 1 Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Hermannsburg Historic Precinct Other Names: Hermannsburg Historic Village Place ID: 105767 File No: 7/08/013/0003 Primary Nominator: 104271 Nomination Date: 12/09/2004 Principal Group: Aboriginal Historic/Contact Site Status Legal Status: 20/09/2004 - Nominated place Admin Status: 25/11/2005 - Assessment by AHC completed Assessment Assessor: Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Alice Springs Distance from town (km): 140 Direction from town: west Area (ha): 3 Address: Larapinta Dr, Hermannsburg, NT 0872 LGA: Unicorporated NT NT Location/Boundaries: About 3ha, 140km west of Alice Springs on Larapinta Drive, comprising Lot 196 (A) township of Hermannsburg as delineated on Survey Plan S2000/59. Assessor's Summary of Significance: Hermannsburg Mission was established by German Lutheran missionaries in 1877 following an arduous 20 month journey from South Australia, at the forefront of pastoral expansion in central Australia. It was managed by Lutheran missionaries and the Lutheran Church from 1877-1982, and is the last surviving mission developed by missionaries from the Hermannsburg Missionary Society in Germany under the influence the German Lutheran community in South Australia. This community was established in 1838 supported by the South Australia Company, and in particular George Fife Angas. The mission functioned as a refuge for Aboriginal people during the violent frontier conflict that was a feature of early pastoral settlement in central Australia. The Lutheran missionaries were independent and outspoken, playing a key role in attempting to mediate conflict between pastoralists, the police and Aboriginal people, and speaking publicly about the violence, sparking heated national debate. -

Outback South Australia & Flinders

A B C Alice Springs D E F G H J K Kulgera QAA Big Red Surveyor NORTHERN TERRITORY NORTHERN TERRITORY LINE Generals Poeppel Corner SOUTH AUSTRALIA LINE Birdsville QUEENSLAND Haddon Corner Major Road Sealed K1 Corner SOUTH AUSTRALIA Mount Dare Hotel SOUTH AUSTRALIA Witjira National Park FRENCH Major Road Unsealed RIG Simpson Desert Mt Woodroffe Dalhousie Conservation Park 1 Springs YANDRUWANDHA 1 Secondary Road Sealed RIG / YAWARRAWARRKA RD RD Secondary Road Unsealed LINE Aparawatatja Strzelecki Community Alberga Goyder 'Cordillo Downs' Other Road Unsealed Fregon WANGKANGURRU / YARLULANDI Lagoon Desert Simpson Desert 'Arrabury' 4WD Only Simpson Desert River Macumba Innamincka Station ANANGU Regional Reserve Regional PITJANTJATJARA Warburton Marla OODNADATTA Reserve YANKUNYTJATJARA Mintabie Crossing Coongie Lakes Explorer’s Way STUART River National Park WESTERN ABORIGINAL Ck Sturt LAND A87 Route Marker Oodnadatta Ck 2 ANTAKIRIJA 2 Stony Walkers Crossing Visitor Information Centre ANANGU PITJANTJATJARA RD 'Kalamurina' RD River Warburton Innamincka YANKUNYTJATJARA Cadney DESERT Desert Aboriginal Cultural Experience PAINTED Homestead TRACK 'Copper Accommodation Hills' KEMPE Mungerannie (Indicated for Outback and Neales Hotel Moomba Flinders Ranges region only) Lake Eyre (No Public SOUTH Great Victoria Desert Tirari Services) Mamungari Con. Park Lake Eyre Cooper Annes Corner Defence North National Park Desert Centre A87 ANNE Tallaringa Elliot TRACK Strzelecki Vokes Hill Woomera Conservation Corner MARALINGA Price Strzelecki Park William QUEENSLAND TJARUTJA THE Con. Lake 3 Creek Regional Desert SOUTH AUSTRALIA 3 ABORIGINAL BEADELL Gregory HWY Park DIERI Reserve LAND Coober Pedy RD See Dog Fence WILLIAM CREEK PASTORAL PROPERTIES Lake Eyre South Outback Cameron The roads in this region pass through working ARABUNNA TRACK 'Muloorina' BIRDSVILLE Corner pastoral properties.