Soil Conservation Board District Plan : Northern Flinders Ranges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity

Biodiversity KEY5 FACTS as hunting), as pasture grasses or as aquarium species Introduced (in the case of some marine species). They have also • Introduced species are been introduced accidentally, such as in shipments of recognised as a leading Species imported grain or in ballast water. cause of biodiversity loss Introduced plants, or weeds, can invade and world-wide. compete with native plant species for space, light, Trends water and nutrients and because of their rapid growth rates they can quickly smother native vegetation. • Rabbit numbers: a DECLINE since Similarly to weeds, many introduced animals compete introduction of Rabbit Haemorrhagic with and predate on native animals and impact on Disease (RHD, also known as calicivirus) native vegetation. They have high reproductive rates although the extent of the decline varies and can tolerate a wide range of habitats. As a result across the State. they often establish populations very quickly. •Fox numbers: DOWN in high priority Weeds can provide shelter for pest animals, conservation areas due to large-scale although they can provide food for or become habitat baiting programs; STILL A PROBLEM in for native animals. Blackberry, for example, is an ideal other parts of the State. habitat for the threatened Southern Brown Bandicoot. This illustrates the complexity of issues associated •Feral camel and deer numbers: UP. with pest control and highlights the need for control •Feral goat numbers: DECLINING across measures to have considered specific conservation Weed affected land – Mount Lofty Ranges the State. outcomes to be undertaken over time and to be Photo: Kym Nicolson •Feral pig numbers: UNKNOWN. -

Sturt National Park

Plan of Management Sturt National Park © 2018 State of NSW and the Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. OEH has compiled this publication in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage that may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. All content in this publication is owned by OEH and is protected by Crown Copyright. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) , subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons . OEH asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018. This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 23 January 2018. Acknowledgments OEH acknowledges that Sturt is in the traditional Country of the Wangkumara and Malyangapa people. This plan of management was prepared by staff of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), part of OEH. -

Biological Conservation 232 (2019) 187–193

Biological Conservation 232 (2019) 187–193 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon A palaeontological perspective on the proposal to reintroduce Tasmanian devils to mainland Australia to suppress invasive predators T ⁎ Michael C. Westawaya, , Gilbert Priceb, Tony Miscamblec, Jane McDonaldb, Jonathon Crambb, ⁎ Jeremy Ringmad, Rainer Grüna, Darryl Jonesa, Mark Collarde, a Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, Environmental Futures Research Institute, N13 Environment 2 Building, Griffith University, Nathan Campus, 170 Kessels Road, Nathan, Brisbane, Queensland 4111, Australia b School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia c School of Social Science, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia d College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, 2500 Campus Road, Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822, USA e Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, British Columbia V5A 1S6, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The diversity of Australia's mammalian fauna has decreased markedly since European colonisation. Species in Australia the small-to-medium body size range have been particularly badly affected. Feral cats and foxes have played a Invasive predator central role in this decline and consequently strategies for reducing their numbers are being evaluated. One such Fossil record strategy is the reintroduction to the mainland of the Tasmanian devil, Sarcophilus harrisii. Here, we provide a Feral cat palaeontological perspective on this proposal. We begin by collating published records of devil remains in Fox Quaternary deposits. These data show that the range of devils once spanned all the main ecological zones in Tasmanian devil Sarcophilus Australia. -

Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 4

NASA/TP—2001–209990 Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 04 F. Espenak and J. Anderson Central Lat,Lng = -28.0 132.0 P Factor = 0.46 Semi W,H = 0.35 0.28 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:40:42 AM High Res World Data [WPD1] WorldMap v2.00, F. Espenak Orthographic Projection Scale = 8.00 mm/° = 1:13915000 Central Lat,Lng = -10.0 26.0 P Factor = 0.31 Semi W,H = 0.70 0.50 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:17:57 AM September 2001 The NASA STI Program Office … in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical science. The NASA Scientific and Technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other Information (STI) Program Office plays a key meetings sponsored or cosponsored by NASA. part in helping NASA maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, techni- cal, or historical information from NASA The NASA STI Program Office is operated by programs, projects, and mission, often con- Langley Research Center, the lead center for cerned with subjects having substantial public NASA’s scientific and technical information. The interest. NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. aeronautical and space science STI in the world. English-language translations of foreign scien- The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional tific and technical material pertinent to NASA’s mechanism for disseminating the results of its mission. -

Broken Hill Complex

Broken Hill Complex Bioregion resources Photo Mulyangarie, DEH Broken Hill Complex The Broken Hill Complex bioregion is located in western New South Wales and eastern South Australia, spanning the NSW-SA border. It includes all of the Barrier Ranges and covers a huge area of nearly 5.7 million hectares with approximately 33% falling in South Australia! It has an arid climate with dry hot summers and mild winters. The average rainfall is 222mm per year, with slightly more rainfall occurring in summer. The bioregion is rich with Aboriginal cultural history, with numerous archaeological sites of significance. Biodiversity and habitat The bioregion consists of low ranges, and gently rounded hills and depressions. The main vegetation types are chenopod and samphire shrublands; casuarina forests and woodlands and acacia shrublands. Threatened animal species include the Yellow-footed Rock- wallaby and Australian Bustard. Grazing, mining and wood collection for over 100 years has led to a decline in understory plant species and cover, affecting ground nesting birds and ground feeding insectivores. 2 | Broken Hill Complex Photo by Francisco Facelli Broken Hill Complex Threats Threats to the Broken Hill Complex bioregion and its dependent species include: For Further information • erosion and degradation caused by overgrazing by sheep, To get involved or for more information please cattle, goats, rabbits and macropods phone your nearest Natural Resources Centre or • competition and predation by feral animals such as rabbits, visit www.naturalresources.sa.gov.au -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

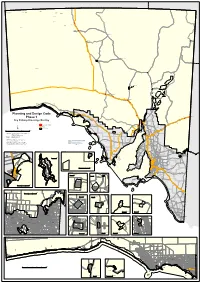

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Northern Flinders Ranges

A B Oodnadatta Track C D Innamincka E F Birdsville Track Strzelecki ROAD CONDITIONS The road surface information on this map Track should be used as a guide only. Local TRACK advice should be sought at all times. LAKES Frome With very few exceptions, the lakes STRZELECKI Arkaroola Paralana 'Mt Lyndhurst' Wilderness Hot Springs 1 shown are dry salt pans and do not Ochre Pits Sanctuary 'North Mulga' 1 indicate a permanent source of water. 'Avondale' 'Umberatana' Mt Painter PASTORAL PROPERTIES Lyndhurst The roads in this region pass through Talc Alf Echo Camp working pastoral properties. Please do Backtrack Barraranna Gorge not leave the road and enter these River 4WD properties without prior permission from Arkaroola 'Yankaninna' Ochre the landholder. Most home steads do Wall not provide tourist facilities and are 83 Wooltana shown on this map for navigational Vulkathunha - Cave purposes. Please respect the property 33 Mainwater Pound and privacy of pastoralists. 'Owieandana' 'Wooltana' Coaleld Illinawortina 'Myrtle Springs' Gammon Ranges 30 4WD TRACKS National Park Pound For more information on 4WD Tracks Gerti Johnson Nepouie please obtain a copy of the 4WD Tracks 'Leigh Monument Weetootla Gorge 2 & Repeater Towers brochure. You may Creek' Balcanoona Gorge 2 need to make an appointment and pay Ck 'Depot NEPABUNNA access fees for some tracks. Copley 45 Springs' ABORIGINAL LAND Leigh Creek Nepabunna Balcanoona Aroona Dam 'Angepena' 54 Italowie Nat. Park H.Q. Fence Arrunha Aroona Iga Warta Gorge Sanctuary 'Maynards Vulkathunha - Gammon Ranges Well' National Park Puttapa 'Wertaloona' Copper King Mine Puttapa Moro Gorge Gap HWY NANTAWARRINA Ediacara 'Warraweena' INDIGENOUS Dog Lake Conservation Lake Reserve Afghan PROTECTED AREA 39 Mon. -

Victoria Nikoloudis 'At Home' in Coober Pedy After

ISSN 1833-1831 Tourist Park Coober Pedy 08 86 725 691 BULLS GARAGE On-site Service Centre Phone: 86 725 036 Tel: 08 8672 5920 https://cooberpedytimes.com Thursday 14 June 2018 VICTORIA NIKOLOUDIS ‘AT HOME’ IN COOBER PEDY AFTER THAILAND FIRE ORDEAL by Margaret Mackay Victoria Nikoloudis, daughter of Coober Pedy’s Jimmy the Runner, and grand-daughter of the late Inge Feug has spent a week in Coober Pedy to be with her dad and to visit close friends after being released from the Royal Adelaide Hospital Burns Unit last week. Through a series of events that went wrong while cooking dinner at her apartment in Thailand on 11 April, 2018 Victoria was rushed to a Thai hospital suffering 30% burns to her upper body. 37 year old Victoria is sharing her story through the Coober Pedy Regional Times, reaching out to thank many of those who came to her aid and to perhaps inspire others who may be facing a serious life challenge of their own. Throughout this ordeal (far from over) Victoria has shown strength and courage that might rival some of history’s finest women warriors. Victoria relived her ordeal for our story: “I was heating up a pot of oil on a portable burner, which is what I use for cooking at home in Chiang Mai Thailand. I had the window open and the was fan on! Margaret Mackay © “While the oil was heating I was dashing around doing washing and other things. Suddenly I noticed smoke and Victoria Nikoloudis just discharged from the Adelaide Burns Unit and at ‘home’ in Coober Pedy with saw the oil was on fire. -

So Far and Yet So Close: Frontier Cattle Ranching in Western Prairie Canada and the Northern Territory of Australia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2015-06 So Far and yet so Close: Frontier Cattle Ranching in Western Prairie Canada and the Northern Territory of Australia Elofsen, Warren M. University of Calgary Press Elofson, W. M. "So Far and yet so Close: Frontier Cattle Ranching in Western Prairie Canada and the Northern Territory of Australia". University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2015. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50481 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca SO FAR AND YET SO CLOSE: FRONTIER CATTLE RANCHING IN WESTERN PRAIRIE CANADA AND THE NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA By Warren M. Elofson ISBN 978-1-55238-795-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

The Flinders Ranges South Australia: Evidence from Leporillus Spp

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A holocene vegetation history of the Flinders Ranges South Australia: evidence from Leporillus spp. (stick-nest rat) middens Lynne McCarthy University of Wollongong Recommended Citation McCarthy, Lynne, A holocene vegetation history of the Flinders Ranges South Australia: evidence from Leporillus spp. (stick-nest rat) middens, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Geosciences, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1962 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A HOLOCENE VEGETATION HISTORY OF THE FLINDERS RANGES SOUTH AUSTRALIA: EVIDENCE FROM LEPORILLUS SPP. (STICK-NEST RAT) MIDDENS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by LYNNE MCCARTHY B.Env.Sc. BSc (Hons.) SCHOOL OF GEOSCIENCES 1999 This work has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University or Institution and, unless acknowledged, is my own work. Lynne McCarthy i ABSTRACT Palaeoecological records for semi-arid and arid environments of Australia are limited due to poor preservation of material in this environmental setting. As a consequence, a Holocene vegetation and climatic record for a large part of the continent is incomplete. Leporillus spp. (stick-nest rat) middens provide a wealth of palaeoecological information for Holocene environments in areas where such records are rare. Eighteen middens from three key sites in the Flinders Ranges (Arkaroola-Mount Painter Sanctuary, Mount Chambers Gorge and Brachina Gorge), were investigated in this project to provide a thorough spatial and temporal coverage of palaeoecological sites.