A Case Study in Gender, Difference and Common

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

EBHR 37 Cover Page.Indd

7 Crossing the Sutlej River: An examination of early British rule in the West Himalayas Arik Moran The challenges entailed in establishing political authority over the mountainous terrain of the Himalayas became particularly pronounced in the modern era, as large-scale centralized states (e.g. British India, Gorkha Nepal) extended their rule over remote parts of the mountain chain. In this novel political setting, the encounters of the representatives of greater powers with their counterparts from subordinate polities were often fraught with clashes, misunderstandings and manipulations that stemmed from the discrepancy between local notions of governance and those imposed from above. This was especially apparent along British India’s imperial frontier, where strategic considerations dictated a cautious approach towards subject states so as to minimize friction with neighbouring superpowers across the border. As a result, the headmen inhabiting frontier zones enjoyed a conspicuous advantage in dealing with their superiors insofar as ‘deliberate misrepresentations and manipulation[s]’ of local practices allowed them to further their aims while retaining the benefits of protection by a robust imperial structure (O’Hanlon 1988: 217). This paper offers a detailed illustration of the complications provoked by these conditions by examining the embroilment of a British East India Company official in a feud between the West Himalayan kingdoms of Bashahr and Kullu (in today’s Himachal Pradesh, India) during the first half of the nineteenth century. After ousting the Gorkha armies from the hills in 1815, Company authorities pursued a policy of minimal interference in the internal affairs of the mountain (pahāṛ ) kingdoms between the Yamuna and Sutlej Rivers, whose rulers were granted an autonomous status under the supervision of a political agent. -

State, Marriage and Household Amongst the Gaddis of North India

GOVERNING MORALS: STATE, MARRIAGE AND HOUSEHOLD AMONGST THE GADDIS OF NORTH INDIA Kriti Kapila London School of Economics and Political Science University of London PhD UMI Number: U615831 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615831 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H cS £ S h S) IS ioaqsci% Abstract This thesis is an anthropological study of legal governance and its impact on kinship relations amongst a migratory pastoralist community in north India. The research is based on fieldwork and archival sources and is concerned with understanding the contest between ‘customary’ and legal norms in the constitution of public moralities amongst the Gaddis of Himachal Pradesh. The research examines on changing conjugal practices amongst the Gaddis in the context of wider changes in their political economy and in relation to the colonial codification of customary law in colonial Punjab and the Hindu Marriage Succession Acts of 1955-56. The thesis investigates changes in the patterns of inheritance in the context of increased sedentarisation, combined with state legislation and intervention. -

Himachal Pradesh in the Indian Himalaya

Mountain Livelihoods in Transition: Constraints and Opportunities in Kinnaur, Western Himalaya By Aghaghia Rahimzadeh A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Louise P. Fortmann, Chair Professor Nancy Lee Peluso Professor Isha Ray Professor Carolyn Finney Spring 2016 Mountain Livelihoods in Transition: Constraints and Opportunities in Kinnaur, Western Himalaya Copyright © 2016 By Aghaghia Rahimzadeh Abstract Mountain Livelihoods in Transition: Constraints and Opportunities in Kinnaur, Western Himalaya by Aghaghia Rahimzadeh Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy and Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Louise P. Fortmann, Chair This dissertation investigates the transformation of the district of Kinnaur in the state of Himachal Pradesh in the Indian Himalaya. I examine Kinnauri adaptation to political, economic, environmental, and social events of the last seven decades, including state intervention, market integration, and climate change. Broadly, I examine drivers of change in Kinnaur, and the implications of these changes on social, cultural, political, and environmental dynamics of the district. Based on findings from 11 months of ethnographic field work, I argue that Kinnaur’s transformation and current economic prosperity have been chiefly induced by outside forces, creating a temporary landscape of opportunity. State-led interventions including land reform and a push to supplement subsistence agriculture with commercial horticulture initiated a significant agrarian transition beginning with India’s Independence. I provide detailed examination of the Nautor Land Rules of 1968 and the 1972 Himachel Pradesh Ceiling of Land Holding Act, and their repercussion on land allocation to landless Kinnauris. -

Spring Congregation 2018 May 23–25 May 28–31 the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts Dear Graduand

spring congregation 2018 may 23–25 may 28–31 the chan centre for the performing arts Dear Graduand, Your graduation began long before this day. It began when you made the choice to study that extra hour, dedicate yourself more deeply, and strive to reach for the degree you had chosen to fully commit your life to pursuing. Many of the people that helped you arrive here today are seated beside you—friends, family, classmates— while others are thinking of you from afar. We are honoured to have given you a place to discover, inspire others and be challenged beyond what you thought was possible. We hope you know, we will always be that place for you. Yours, UBC TABLE OF CONTENTS The Graduation Journey 2 Lists of Spring 2018 Graduating Students Graduation Traditions 4 Wednesday, May 23, 2018 8:30am 32 Chancellor’s Welcome 6 11:00am 36 President’s Welcome 8 1:30pm 39 Musqueam Welcome 10 4:00pm 43 Honorary Degree Recipients 12 Thursday, May 24, 2018 8:30am 47 The Board of Governors & Senate 16 11:00am 52 1:30pm 55 Honoring Significant 18 4:00pm 59 Accomplishments & Contributions Friday, May 25, 2018 8:30am 63 Scholarships, Medals & Prizes 19 11:00am 66 1:30pm 69 Schedule of Ceremonies 24 4:00pm 72 Monday, May 28, 2018 8:30am 75 11:00am 78 1:30pm 81 4:00pm 85 Tuesday, May 29, 2018 8:30am 89 11:00am 92 1:30pm 95 4:00pm 98 Wednesday, May 30, 2018 8:30am 101 11:00am 104 1:30pm 107 4:00pm 110 Thursday, May 31, 2018 8:30am 113 11:00am 116 1:30pm 120 4:00pm 123 Acknowledgements 125 O Canada 125 Alumni Welcome 129 A General Reception will follow each Ceremony at the Flag Pole Plaza. -

Annual Report 2018- 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018- 2019 ZAKIR HUSAIN DELHI COLLEGE JAWAHAR LAL NEHRU MARG, NEW DELHI-110002 WEBSITE: www.zakirhusaindelhicollege.ac.in 011-23232218, 011-23232219 Fax: 011-23215906 Contents Principal’s Message ............................................................................................................................. 5 Coordinator’s Message ........................................................................................................................ 6 Co-ordinators of Annual Day Committees .......................................................................................... 7 Members of Annual Day Committees ................................................................................................. 8 Annual Report Compilation Committee ............................................................................................ 10 Reports of College Committees ......................................................................................................... 11 Memorial Lecture Committee ..................................................................................................... 12 Arts and Culture Society ............................................................................................................. 12 B. A. Programme Society ........................................................................................................... 16 Botany Society: Nargis ............................................................................................................... 16 -

The Panjab, North-West Frontier Province, and Kashmir

1 Chapter XVII CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV CHAPTER V CHAPTER VI CHAPTER VII CHAPTER VIII CHAPTER IX CHAPTER X CHAPTER XI CHAPTER XII CHAPTER XIII CHAPTER XIV CHAPTER XV CHAPTER XVI CHAPTER XVII CHAPTER XVIII CHAPTER XIX CHAPTER XX CHAPTER XXI CHAPTER XXII CHAPTER XXIII CHAPTER XXIV CHAPTER XXV Chapter XXX. CHAPTER XXVI CHAPTER XXVII CHAPTER XXVIII The Panjab, North-West Frontier Province, and by Sir James McCrone Douie 2 CHAPTER XXIX CHAPTER XXX The Panjab, North-West Frontier Province, and by Sir James McCrone Douie The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Panjab, North-West Frontier Province, and Kashmir, by Sir James McCrone Douie This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Panjab, North-West Frontier Province, and Kashmir Author: Sir James McCrone Douie Release Date: February 10, 2008 [eBook #24562] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PANJAB, NORTH-WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE, AND KASHMIR*** E-text prepared by Suzanne Lybarger, Asad Razzaki, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations and maps. See 24562-h.htm or 24562-h.zip: (http://www.gutenberg.net/dirs/2/4/5/6/24562/24562-h/24562-h.htm) or (http://www.gutenberg.net/dirs/2/4/5/6/24562/24562-h.zip) Transcriber's note: Text enclosed between tilde characters was in bold face in the original book (~this text is bold~). -

Bhutto a Political Biography.Pdf

Bhutto a Political Biography By: Salmaan Taseer Reproduced By: Sani Hussain Panhwar Member Sindh Council, PPP Bhutto a Political Biography; Copyright © www.bhutto.org 1 CONTENTS Preface .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 1 The Bhuttos of Larkana .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 2 Salad Days .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 3 Rake’s Progress .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 4 In the Field Marshal’s Service .. .. .. .. .. 35 5 New Directions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 45 6 War and Peace 1965-6 .. .. .. .. .. .. 54 7 Parting of the Ways .. .. .. .. .. .. 69 8 Reaching for Power .. .. .. .. .. .. 77 9 To the Polls .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 102 10 The Great Tragedy .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 114 11 Reins of Power .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 125 12 Simla .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 134 13 Consolidation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 147 14 Decline and Fall .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 163 15 The Trial .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 176 16 The Bhutto Conundrum .. .. .. .. .. 194 Select Bibliography .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 206 Bhutto a Political Biography; Copyright © www.bhutto.org 2 PREFACE Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was a political phenomenon. In a country where the majority of politicians have been indistinguishable, grey and quick to compromise, he stalked among them as a Titan. He has been called ‘blackmailer’, ‘opportunist’, ‘Bhutto Khan’ (an undisguised comparison with Pakistan’s military dictators Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan) and ‘His Imperial Majesty the Shahinshah of Pakistan’ by his enemies. Time magazine referred to him as a ‘whiz kid’ on his coming to power in 1971. His supporters called him Takhare Asia’ (The Pride of Asia) and Anthony Howard, writing of him in the New Statesman, London, said ‘arguably the most intelligent and plausibly the best read of the world’s rulers’. Peter Gill wrote of him in the Daily Telegraph, London: ‘At 47, he has become one of the third world’s most accomplished rulers.’ And then later, after a change of heart and Bhutto’s fall from power, he described him as ‘one of nature’s bounders’. -

Pre-School Data & All Base DTD 06-01-2020.Xlsx

DELHI PUBLIC SCHOOL, DWARKA PRE-SCHOOL ADMISSION PROCESS 2020-2021 LIST OF REGISTERED APPLICANTS (Registration Number wise) S.No Registration No. Child's Name Father's Name Mother's Name 1 D2021/PS/0001 SHANAYA SINHA ROHIT SINHA SHIVALI SINHA 2 D2021/PS/0003 ANANYA TIWARI SATYA PRAKASH TIWARI NEELAM TIWARI 3 D2021/PS/0005 ROOHANI TANEJA ANKIT TANEJA DEEPIKA LUTHRA TANEJA 4 D2021/PS/0006 DAISHA SETH MUDIT SETH NIDHI AGGARWAL 5 D2021/PS/0007 DIVIK BAHL HIMANSHU BAHL NEHA BAHL 6 D2021/PS/0008 NIKUNJ AGGARWAL AADARSH AGGARWAL ANKITA AGARWAL 7 D2021/PS/0009 RANVEER SINGH INDERPREET SINGH MANPREET KAUR 8 D2021/PS/0010 REYANSH THAKUR GIRISH THAKUR SUNITA THAKUR 9 D2021/PS/0011 AADVIK SHARMA DEEPAK SHARMA VANI SHARMA 10 D2021/PS/0012 MOKSH VASHISHTH VINOD SHARMA NEHA SHARMA 11 D2021/PS/0013 SHREYA ARORA HIMANSHU ARORA SHREYA DEVGUN 12 D2021/PS/0014 MANAN SOOD RAHUL SOOD DEEPALI SOOD 13 D2021/PS/0015 DALJEET SINGH GURDEEP SINGH RITU SHARMA 14 D2021/PS/0016 SHREYA VARSHNEY RAVI VARSHNEY NAINSI 15 D2021/PS/0017 AADVIK PAL NARESH KUMAR PAL RICHA PAL 16 D2021/PS/0018 KRISHIV AGGARWAL ANKIT AGGARWAL GARIMA SINGH 17 D2021/PS/0019 RUDRANSH SHARMA NAKUL SHARMA POONAM MALHOTRA 18 D2021/PS/0020 RIYARTH UPADHAYAYA MANISH UPADHAYAYA GEETA UPADHAYAYA 19 D2021/PS/0021 NISHANT APOORVA RAI STEPHEN RAI JANET RAI 20 D2021/PS/0022 JOHANN KHARIAP VALIAVILA BIPIN RAJDAS VALIAVILA RIDALANG KHARIAP 21 D2021/PS/0023 KARANVEER SINGH KALRA UPKAR SINGH KALRA SHWETA KALRA 22 D2021/PS/0024 MAIRA NEGI PRADEEP SINGH NEGI KAMINI NEGI 23 D2021/PS/0025 NAIRA AGGARWAL HARISH CHANDER -

Conflict and Disease an Analysis of Endem Ic Polio in Northern Pakistan

CONFLICT AND DISEASE AN ANALYSIS OF ENDEM IC POLIO IN NORTHERN PAKISTAN Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy Capstone Project Submitted by Randall Quinn December 15, 2015 © 2015 Quinn http://fletcher.tufts.edu Quinn The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Conflict and Disease An Analysis of Endemic Polio in Northern Pakistan Randall M Quinn Graduate Thesis 12-15-2015 1 Conflict and Disease Quinn Abstract Polio is a disease that held a profound impact on much of the world’s population for the first half of the 20th Century. Today it is barely an afterthought throughout the developed world, as vaccines invented in the 1950’s greatly reduced the disease burden, gradually at first and then precipitously with the onset of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988. Despite great progress, there is one remaining reservoir of wild poliovirus that remains in the world today and prevents any declaration of victory against the disease. The reservoir is centered in northern Pakistan and frequently infects populations on both sides of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. A number of factors have contributed to this being the last global holdout. This paper aims to explore those factors and project potential policy solutions. Given the highly infectious nature of the disease and the frequent movement of people in and through this region, all of the elements are there for a global resurgence, highlighting the importance of resolving the issue as quickly and efficiently as possible. 2 Conflict and Disease Quinn Table of Contents Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................... -

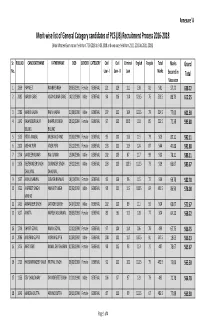

Merit-Wise List of General Category Candidates of PCS (JB)

Annexure 'A' Merit-wise list of General Category candidates of PCS (JB) Recruitment Process 2016-2018 (Main Written Examination held from 7.09.2018 to 9.09.2018 and viva voce held from 21.11.2018 to 28.11.2018) Sr. ROLLNO CANDIDATENAME FATHERNAME DOB GENDER CATEGORY Civil Civil Criminal English Punjabi Total Marks Grand No. Law - I Law - II Law Marks Secured in Total Viva voce 1 1839 PAPNEET RANBIR SINGH 09/05/1991 Female GENERAL 121 129 111 138 82 581 57.22 638.22 2 2082 KARUN GARG VIJAY KUMAR GARG 14/12/1989 Male GENERAL 94 116 114 123.5 76 523.5 88.75 612.25 3 1783 MANIK KAURA RAJIV KAURA 31/08/1990 Male GENERAL 107 112 104 122.5 79 524.5 77.00 601.50 4 1142 RAJANDEEP KAUR BHARPUR SINGH 28/12/1984 Female GENERAL 97 135 88.5 118 85 523.5 72.38 595.88 BILLING BILLING 5 1515 RITIKA KANSAL KRISHAN CHAND 22/02/1990 Female GENERAL 95 100 116 115 79 505 87.11 592.11 6 2100 MEHAK PURI VIVEK PURI 25/12/1991 Female GENERAL 103 111 119 124 87 544 47.88 591.88 7 1734 SANDEEP KUMAR RAJ KUMAR 13/04/1986 Male GENERAL 102 105 87 117 99 510 78.11 588.11 8 1306 REETBRINDER SINGH GURJINDER SINGH 19/12/1991 Male GENERAL 103 115 115.5 112.5 73 519 66.67 585.67 DHALIWAL DHALIWAL 9 1957 ANJALI NARWAL SUBASH NARWAL 14/10/1991 Female GENERAL 95 136 96 115 72 514 68.78 582.78 10 1023 JASPREET SINGH AMARJIT SINGH 02/02/1992 Male GENERAL 98 101 115 108.5 69 491.5 86.50 578.00 MINHAS 11 1455 AMANDEEP SINGH JATINDER SINGH 24/07/1992 Male GENERAL 102 110 89 111 92 504 68.67 572.67 12 1627 ANKITA NARESH AGGARWAL 09/03/1993 Female GENERAL 89 98 112 128 77 504 64.22