Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, Haer No. Ca-2273

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRM Bulletin Vol. 12, No. 4 (1989)

Cfffl BULLETIN Volume 12: No. 4 Cultural Resources Management • National Park Service 1989 A Technical Bulletin for Parks, Federal Agencies, States, Local Governments, and the Private Sector Difficult Choices and Hard-Won Successes in Maritime Preservation reserving the remnants of America's life, times, and travails. Scores of wharves, and working waterfronts Pmaritime past poses special chal lighthouses, lifesaving stations, and that survived the decline of America lenges and problems. Ships were built other marine structures were built on as a seafaring nation often have not to last for a few decades, and then, if isolated shores, on surf-tossed survived waterfront redevelopment not on the bottom, were torn apart beaches, or on crumbling cliffs. Sub and urban renewal. with sledges, axes, or cutting torches jected to the powerful fury of ocean Ships, lighthouses, and other mari by shipbreakers. Sailors lived a hard waves, and the corrosive salt air of time relics are often saved by people life at sea and ashore; often illiterate, the marine environment, many suc they left little written record of their cumbed to the sea. Those buildings, (continued on page 2) Grim Realities, High Hopes, Moderate Gains: The State of Historic Ship Preservation James P. Delgado hile maritime preservation is maritime cultural resources were historic vessels slowly followed, in Wconcerned with all aspects of the originally created to serve or assist large part after the Depression, with Nation's seafaring past, including ships and shipping. the establishment of maritime lighthouses, shipyards, canals, and Historic ship preservation in the museums that included large ships— sail lofts, the major effort and atten United States dates to the last cen Mystic Seaport being the first major tion has been devoted to historic tury, when public interest and outcry example. -

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 MARITIME HERITAGE OF THE UNITED STATES NHL THEME STUDY LARGE VESSELS FERRY BERKELEY Page 1 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Berkeley Other Name/Site Number: Ferry Berkeley 2. LOCATION Street & Number: B Street Pier Not for publication: City/Town: San Diego Vicinity: State: CA County: San Diego Code: 073 Zip Code: 92101 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s):_ Public-local: District:_ Public-State: __ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: X Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ____ buildings ____ sites ____ structures ____ objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: NFS FORM 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 FERRY BERKELEY Page 2 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Chronology of Pier 70 Area

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number 8 Page 4 Chronology of the Pier 70 District The following chronology outlines significant events associated with the Pier 70 Historic District including the history of Union Iron Works, Bethlehem Steel, Pacific Rolling Mills, Risdon Iron and Locomotive Works, U. S. Steel Corp., and U. S. Navy, all land owners in the district during the period of significance. This chronology also includes significant events that shaped the United States steel hull shipbuilding industry. 1849 Donahue brothers open California’s first iron foundry during the height of the California Gold Rush 1853 Peter Donahue becomes the sole-owner and renames the works the Union Iron Works 1857 Bethlehem Steel Company starts as an iron works in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania c.1860 Wooden shipbuilders John North and Henry Owen move to Potrero Point 1861-1865 Civil War 1865 Irving M. Scott becomes a partner and Peter Donahue retires 1868 Pacific Rolling Mills opens on Potrero Point as the first steel mill on West Coast c.1870s Irish Hill neighborhood established Union Iron Works purchases Henry Owen’s shipyard 1884 The Union Iron Works shipyard opens 1885 First U. S. Naval contract for steel hull ship given to John Roach’s Delaware River Iron Shipbuilding and Engine Works shipyard (“ABCD ships”, or Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, and Dolphin) San Francisco iron workers’ strike successfully for higher -

DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial

State of California & The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial Page 1 of 32 *NRHP Status Code *Resource Name or # (Assigned by recorder) Potrero Point Historic District D1. Historic Name Potrero Point/Lower Potrero D2. Common Name: Central Waterfront *D3. Detailed Description (Discuss coherence of the district, its setting, visual characteristics, and minor features. List all elements of district.): The Potrero Point Historic District (also referred to as the Central Waterfront) is located in the Potrero Hill district of San Francisco on the western side of San Francisco Bay in the City of San Francisco between Mission Creek on the north and Islais Creek to the south. The approximately 500-acre area is more precisely described as a roughly rectangular district bounded by Sixteenth Street to the north, San Francisco Bay to the east, Islais Creek to the south, and U.S. Interstate 280 to the west. The area measures approximately 1.3 miles from north to south, and approximately 0.6 miles wide from east to west. (See Continuation Sheet, Pg. 2) *D4. Boundary Description (Describe limits of district and attach map showing boundary and district elements.): The Potrero Point (Central Waterfront) area is enclosed within a rectangle formed by the following streets and natural features: Beginning at the northwest corner of Pennsylvania and Sixteenth streets, the northern boundary of the area extends east along Sixteenth Street into San Francisco Bay. The boundary turns ninety degrees and heads south through the bay encompassing the entirety of Piers 70 and 80. At Islais Creek Channel, the boundary makes a ninety degree turn and heads west along the southern shore of the channel. -

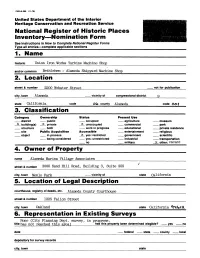

1. Name 6. Representation in Existing Surveys

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register off Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Union Iron Works Turbine Machine Shop and/or common Bethlehem - Alameda Shipyard Machine Shop 2. Location street & number 2200 Webster Street city, town Alameda vicinity of congressional district 9 state California code county Alameda code Oof 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private x unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process . x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military x other: vacant 4. Owner of Property name Alameda Marina Village Associates street & number 3000 Sand Hill Road, Building 3, Suite 255 city, town Menlo Park vicinity of state California 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Alameda County Courthouse street & number 1225 Fallen Street city, town Oakland state California 6. Representation in Existing Surveys None (City Planning Dept. survey, in progress, title has not reached this area)________has this property been determined elegible? yes no date . federal . state . county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered x original site _x_good __ruins _x_ altered __moved date __ fair? * __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance See Continuation Sheet - page 8. -

Guide to the William A. Baker Collection

Guide to The William A. Baker Collection His Designs and Research Files 1925-1991 The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collections of MIT Museum Kurt Hasselbalch and Kara Schneiderman © 1991 Massachusetts Institute of Technology T H E W I L L I A M A . B A K E R C O L L E C T I O N Papers, 1925-1991 First Donation Size: 36 document boxes Processed: October 1991 583 plans By: Kara Schneiderman 9 three-ring binders 3 photograph books 4 small boxes 3 oversized boxes 6 slide trays 1 3x5 card filing box Second Donation Size: 2 Paige boxes (99 folders) Processed: August 1992 20 scrapbooks By: Kara Schneiderman 1 box of memorabilia 1 portfolio 12 oversize photographs 2 slide trays Access The collection is unrestricted. Acquisition The materials from the first donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. The materials from the second donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by the estate of Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. Copyright Requests for permission to publish material or use plans from this collection should be discussed with the Curator of the Hart Nautical Collections. Processing Processing of this collection was made possible through a grant from Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. 2 Guide to The William A. Baker Collection T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Biographical Sketch ..............................................................................................................4 Scope and Content Note .......................................................................................................5 Series Listing -

An Analysis of Union Iron Works Foreman's Index Cards Dated 1908-1918 KEITH TERRY

Research Report: An Analysis of Union Iron Works Foreman's Index Cards Dated 1908-1918 KEITH TERRY Index Index 2o5 Index ofTables and Figures Introduction 206 A Short I lisrory of the Union Iron Works 206 I listoriography 207 An Overview of the Workers ao8 General I)emographie Overview 208 W’age Overview: 212 Employment Length Overview: 214 Analysis 215 Nationality and Race: 215 Wages: 216 Employment Length, Worker Age, and Labor Division: 218 Coneltision: 219 Index ofTables and Figures Table t: Average Age 209 Table : \Vorker Skill Level 209 Table : Summary of Nationality 210 ‘Fable : Detailed Nativity 210-211 Figure i: Average \\agc By Year 212 lable 5: Surninan’ \Vage I)ata 213 Table 6: Employment Length 214 fable : Nationality and Wages 215 ‘Fable 8: Nationality and Skill Level 216 ‘Fable : A Journeyman’s Wage Increases, 1917-1918 217 Figtire 2: Average Age of\Vorkers By Year 219 Image r: Sample Card — Front 221 Image 2: Sample Card — Back 221 Image : Card Storage Box 222 Image : Cart Loaded W’ith Boxes 222 Ex POST FACTO 206 This paper analyzes previously unused primary sotiree data, and attempts to place it in its proper historiographical context. The data was gathered during a spring 2007 internship supporting a submission to the National Register of I listoric Places. lThc submission is for the Port of San Francisco, and Dr. Marjorie Dobkin is the consulting historian in charge of the submission. The data analyzed is a subset of a collection of Union Iron Works Foreman’s Index Cards housed at the San Francisco Maritime Museum Library in Fort Mason, covering the period of 1908-1918. -

Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey Summary Report and Draft Context Statement

Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey San Francisco Planning Department October 2000–September 2001, Page 1 Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey Summary Report and Draft Context Statement Figure 1: View from Jones and California Streets, looking toward Mission Bay, c. 1867. The activity which is the subject of this Cultural Resources Survey has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. October 2000 – October 2001 Prepared by: San Francisco Planning Department Acknowledging the contributions of: Central Waterfront Survey Advisory Committee San Francisco Architectural Heritage Dogpatch Neighborhood Association Page and Turnbull, Architects Central Waterfront Cultural Resources Survey San Francisco Planning Department October 2000–September 2001, Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Mayor Willie L. Brown, Jr. Planning Commission Anita Theoharis, President William Fay, Vice-President Roslyn Baltimore Hector Chinchilla Cynthia Joe Myrna Lim Jim Salinas, Sr. Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board Tim Kelley, President Suheil Shatara, Vice-President Ina Dearman Paul Finwall Nancy Ho-Belli -

Historic Context Statement

HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT MARINSHIP Sausalito, California June 2011 Prepared for Community Development Department Sausalito, California Prepared by San Francisco, California Table of Contents I. Introduction................................................................................................................... 1 A. Purpose....................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Definition of Geographical Area.................................................................................................. 3 C. Identification of Historic Contexts and Periods of Significance ................................................. 3 II. Methodology .................................................................................................................. 4 III. Identification of Existing Historic Status......................................................................... 5 A. Here Today.................................................................................................................................. 5 B. City of Sausalito Historical Inventory .......................................................................................... 5 C. California Historical Resources Information System................................................................... 5 D. Other Surveys and Technical Reports........................................................................................ 6 IV. Historic Contexts...........................................................................................................7 -

Moore Dry Dock Company Ships Plans, 1768-1962

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6d5nf1zx No online items Finding Aid to the Moore Dry Dock Company Ships Plans, 1768-1962, This description was produced by the Historic Documents Department of San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. Historic Documents Department San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park National Park Service Third Floor, Building E, Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Phone: 415-561-7030 Fax: 415-556-3540 Contact Information at: www.nps.gov/safr/historyculture/researchcontact.htm All written inquiries should include your name, mailing address, and telephone numbers. 2007 Finding Aid to the Moore Dry HDC 1065 1 Dock Company Ships Plans, 1768-1962, Finding Aid to the Moore Dry Dock Company ships plans, 1768-1962, Collection Number: HDC 1065 San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Historic Documents Department San Francisco, California Contact Information: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Third Floor, Building E, Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Phone: 415-561-7030 Fax: 415-556-3540 All written inquiries should include your name, mailing address, and telephone numbers. Processed by: Mary Gentry Date Completed: 4/4/2008 Encoded by: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, Historic Documents Department Summary Title: Moore Dry Dock Company ships plans, Date: 1768-1962, Date (bulk): bulk 1916-1954 Collection No: HDC 1065 Creator: Moore Dry Dock Company Moore Shipbuilding Company Moore & Scott Iron Works Extent: 21266 items. Repository: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park (Calif.) Historic Documents Department Building E, Fort Mason San Francisco, California 94123 Abstract: The Moore Dry Dock Company Ships Plans collection (HDC 1065) consists of naval architecture and marine engineering drawings from the Moore Dry Dock Company of Oakland, CA. -

Pa3529data.Pdf

{:, \ F f) Httt2~ PHILJt HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD ,,,.,_ 7 U.S.S. OLYMPIA HAER No. PA-428 Location: At the Independence Seaport Museum, Penn's Landing, 211 South Columbus Boulevard & Walnut Street on the Delaware River, in the City of Philadelphia, County of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Zone Easting Northing UTM Coordinates: 18 487292 4421286 Quad: Philadelphia, PA. - N.J. 1:24000 Dates of Construction: Authorized September 7, 1888, Keel laid June 17, 1891, Launched November 5, 1892, Commissioned February 5, 1895 Builder: Union Iron Works, San Francisco, California Official Number: C-6 (original designation) Cost: $1,796,000 Specifications: Protected cruiser, displacement 5870 tons, length 344 feet, beam 53 feet, draft 21.5 feet, maximum speed 21.686 knots, 6 boilers producing 17,313 horsepower. twin screws-triple expansion engines. Original Armament: 4 - 8 11 rifles 14 - 6 pounders 10 - 5" rifles 6 - 1 pounders 6 - torpedo tubes Complement: 34 officers; 440 enlisted men Present Owner: Independence Seaport Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Present Use: Decommissioned. National memorial and maritime museum. Significance: U.S.S. Olympia is a partially armored or protected cruiser which was constructed as part of a congressional program to build a new steel United States navy prior to the tum of the century. Her innovative design incorporated modern armament, high speed engines and armor shielding the magazines and propulsion machinery. She is the oldest extant steel hulled warship in the world. The U.S.S. Olympia was the flagship of Admiral George Dewey's victorious task force at the battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898. During the first two decades of the 19th century she protected American lives and interests in Panama, Dominican Republic, Murmansk (Russia), Croatia and Serbia. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Union Iron Works Historic District_______________________________ Other names/site number: Potrero Works, Union Yard, Bethlehem Steel Yard, Potrero Yard, San Francisco Yard _____________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _N/A__________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing.) ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: South of Illinois Street between 18th and 22nd Streets City or town: San Francisco State: California County: San Francisco _ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for