National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of San Pablo Affordable Housing Strategy

CITY OF SAN PABLO AFFORDABLE HOUSING STRATEGY Prepared for: City of San Pablo November 9, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 5 Effects of COVID-19 on Housing Affordability ..................................................................................... 5 Process for Developing the AHS .......................................................................................................... 6 EXISTING CONDITIONS ....................................................................................................................... 8 Housing Supply ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Existing Housing Affordability Needs ............................................................................................... 15 Existing Resources, Policies, and Programs .................................................................................... 21 RESIDENTIAL MARKET CONDITIONS IN SAN PABLO ...................................................................... 27 Residential Market Supply and Trends ............................................................................................ 27 Opportunities and Constraints for Development ............................................................................ 34 OVERVIEW OF THE IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ................................................................................. -

CRM Bulletin Vol. 12, No. 4 (1989)

Cfffl BULLETIN Volume 12: No. 4 Cultural Resources Management • National Park Service 1989 A Technical Bulletin for Parks, Federal Agencies, States, Local Governments, and the Private Sector Difficult Choices and Hard-Won Successes in Maritime Preservation reserving the remnants of America's life, times, and travails. Scores of wharves, and working waterfronts Pmaritime past poses special chal lighthouses, lifesaving stations, and that survived the decline of America lenges and problems. Ships were built other marine structures were built on as a seafaring nation often have not to last for a few decades, and then, if isolated shores, on surf-tossed survived waterfront redevelopment not on the bottom, were torn apart beaches, or on crumbling cliffs. Sub and urban renewal. with sledges, axes, or cutting torches jected to the powerful fury of ocean Ships, lighthouses, and other mari by shipbreakers. Sailors lived a hard waves, and the corrosive salt air of time relics are often saved by people life at sea and ashore; often illiterate, the marine environment, many suc they left little written record of their cumbed to the sea. Those buildings, (continued on page 2) Grim Realities, High Hopes, Moderate Gains: The State of Historic Ship Preservation James P. Delgado hile maritime preservation is maritime cultural resources were historic vessels slowly followed, in Wconcerned with all aspects of the originally created to serve or assist large part after the Depression, with Nation's seafaring past, including ships and shipping. the establishment of maritime lighthouses, shipyards, canals, and Historic ship preservation in the museums that included large ships— sail lofts, the major effort and atten United States dates to the last cen Mystic Seaport being the first major tion has been devoted to historic tury, when public interest and outcry example. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 MARITIME HERITAGE OF THE UNITED STATES NHL THEME STUDY LARGE VESSELS FERRY BERKELEY Page 1 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Berkeley Other Name/Site Number: Ferry Berkeley 2. LOCATION Street & Number: B Street Pier Not for publication: City/Town: San Diego Vicinity: State: CA County: San Diego Code: 073 Zip Code: 92101 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s):_ Public-local: District:_ Public-State: __ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: X Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ____ buildings ____ sites ____ structures ____ objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: NFS FORM 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 FERRY BERKELEY Page 2 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Chronology of Pier 70 Area

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number 8 Page 4 Chronology of the Pier 70 District The following chronology outlines significant events associated with the Pier 70 Historic District including the history of Union Iron Works, Bethlehem Steel, Pacific Rolling Mills, Risdon Iron and Locomotive Works, U. S. Steel Corp., and U. S. Navy, all land owners in the district during the period of significance. This chronology also includes significant events that shaped the United States steel hull shipbuilding industry. 1849 Donahue brothers open California’s first iron foundry during the height of the California Gold Rush 1853 Peter Donahue becomes the sole-owner and renames the works the Union Iron Works 1857 Bethlehem Steel Company starts as an iron works in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania c.1860 Wooden shipbuilders John North and Henry Owen move to Potrero Point 1861-1865 Civil War 1865 Irving M. Scott becomes a partner and Peter Donahue retires 1868 Pacific Rolling Mills opens on Potrero Point as the first steel mill on West Coast c.1870s Irish Hill neighborhood established Union Iron Works purchases Henry Owen’s shipyard 1884 The Union Iron Works shipyard opens 1885 First U. S. Naval contract for steel hull ship given to John Roach’s Delaware River Iron Shipbuilding and Engine Works shipyard (“ABCD ships”, or Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, and Dolphin) San Francisco iron workers’ strike successfully for higher -

DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial

State of California & The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial Page 1 of 32 *NRHP Status Code *Resource Name or # (Assigned by recorder) Potrero Point Historic District D1. Historic Name Potrero Point/Lower Potrero D2. Common Name: Central Waterfront *D3. Detailed Description (Discuss coherence of the district, its setting, visual characteristics, and minor features. List all elements of district.): The Potrero Point Historic District (also referred to as the Central Waterfront) is located in the Potrero Hill district of San Francisco on the western side of San Francisco Bay in the City of San Francisco between Mission Creek on the north and Islais Creek to the south. The approximately 500-acre area is more precisely described as a roughly rectangular district bounded by Sixteenth Street to the north, San Francisco Bay to the east, Islais Creek to the south, and U.S. Interstate 280 to the west. The area measures approximately 1.3 miles from north to south, and approximately 0.6 miles wide from east to west. (See Continuation Sheet, Pg. 2) *D4. Boundary Description (Describe limits of district and attach map showing boundary and district elements.): The Potrero Point (Central Waterfront) area is enclosed within a rectangle formed by the following streets and natural features: Beginning at the northwest corner of Pennsylvania and Sixteenth streets, the northern boundary of the area extends east along Sixteenth Street into San Francisco Bay. The boundary turns ninety degrees and heads south through the bay encompassing the entirety of Piers 70 and 80. At Islais Creek Channel, the boundary makes a ninety degree turn and heads west along the southern shore of the channel. -

QUINCY, MA (Boston Metro)

Corporate BJ's GAS Station QUINCY, MA (Boston Metro) REPRESENTATIVES PHOTO 30 Liberty St Quincy, MA 02169 SRC NNN Investments Eion Snell of Berger Realty Group, Inc. Net Lease Specialist 1490 Delgany St #623 954 629-6215 Denver, CO 80202 [email protected] CONFIDENTIALITY DISCLOSURE This is a confidential disclosure memorandum intended solely for your limited use and benefit in determining whether you desire to express further interest into the acquisition of the Subject Property. This memorandum contains selected information pertaining to the Property and does not purport to be a representation of the state of affairs of the Owner or the Property, to be all-inclusive or to contain all or part of the information which prospective investors may require to evaluate a purchase of real property. All financial projections and information are provided for general reference purposes only and are based on assumptions relating to the general economy, market conditions, competition, and other factors beyond the control of the Owner and/or Berger Reatly Group, Inc. Therefore, all projections, assumptions, and other information provided and made herein are subject to material variation. All references to acreages, square footages, and other measurements are approximations. Additional information and an opportunity to inspect the Property will be made available to all interested and qualified prospective purchasers. Neither the Owner or Berger Reatly Group Inc., nor any of their respective directors, officers, affiliates, agents, or representatives are making any representation or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of this memorandum or any of its contents, and no legal commitment or obligation shall arise by reason of your receipt of this memorandum or use of its contents; and you are to rely solely on your own investigations and inspections of the Property in evaluating a possible purchase of the real property. -

Boston, Massachusetts 02129 Telephone: (617) 242 -6000

4 MASSACHUSETTS WATER RESOURCES AUTHORITY Charlestown Navy Yard 100 First Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02129 Telephone: (617) 242 -6000 April 24, 1989 Board of Directors John P. DeVillars, Chairman John J. Carroll Robert J. Ciolek William A. Darity Lorraine M. Downey Anne Bingham, Esq. Anthony V. Fletcher Charles Lyons Office of General Counsel Joseph A. MacRtchlDepartment of Environmental Quality Engineering Samuel G. MygattEniomtaQult Thomas E. Reilly, Jr.One Winter Street Walter J. Ryan, Jr. Boston, MA 02108 Executive Director Restriction Paul F.Levy RE: Fore River Staging Area Land-Use Dear Ms. Bingham: I wish to acknowledge receipt of a revised draft of the land-use restriction document, which you sent to MWRA by telecopier on Friday afternoon. We would like an opportunity to discuss this draft further with you and with the MWRA's Fore River Advisory Task Force before the document is made available for broader public distribution and comments. The document you sent us contains several substantive changes from the one which Gary Wilson of MWRA forwarded to you on January 10 (that draft was labelled December 20, 1988). Chief among these is the reintroduction of language excluding uses of the site for other than commercial or industrial purposes. This language appears to be overly restrictive. Our November 20, 1988 draft called for all activities at the site (as these are defined in the Procedures) to be performed in accordance with the Proce- dures. This we thought sufficiently addressed DEQE's concern. S - Anne Bingham, Esq. April 24, 1989 Page 2 I would look forward to discussing the draft land-use restriction with you and MWRA legal staff at your earliest convenience. -

Drawings Traced from Scans Located in the Maritime Administration Collection at the Museum of American History

HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD SAUGATUCK (AO-75) HAER No. VA-128 Location: James River Reserve Fleet, Newport News vicinity, Virginia Rig / Type of Craft: T2-SE-A1/Auxiliary Trade: Tanker Class: Suamico Hull No.: AO-75 Principal Dimensions: Length (oa): 523'-6" Beam: 68' Draft: 30' Displacement: 5,730 (lt) or 21,880 (fl) Gross tonnage: 10,448 tons Service speed: 15-½ knots (The listed dimensions are as built, but it should be noted that draft, displacement, and tonnages were subject to alteration over time as well as variations in measurement.) Dates of Construction: Keel laying: 20 August 1942 Launching: 7 December 1942 Delivery: 21 December 1942 Designer: U.S. Maritime Commission Builder: Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, Chester, Pennsylvania Present Owner: U.S. Maritime Administration Disposition: Scrapped in June 2006 Significance: Saugatuck is representative of the T2-SE-A1 tanker class, which became the workhorse for the U.S. Navy during World War II. There were 481 tankers constructed in this category under the U.S. Maritime Commission’s SAUGATUCK HAER No. VA-128 Page 2 Emergency Program between 1942 and 1945. These auxiliaries serviced the fleets engaged around the globe. Members of this class served in the U.S. Navy, Naval Transportation Service, and Military Sea Transportation Service—later Military Sealift Command. Historian: Brian Clayton, summer 2006 Project Information: This project is part of the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), a long-range program to document historically significant engineering and industrial works in the United States. The Heritage Documentation Programs of the National Park Service, U.S. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Judy Baca

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Judy Baca, SPARC and A Chicana Mural Movement: Reconstructing U.S. History Through Public Art A dissertation in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Juan Pablo Mercado 2018 ã Copyright by Juan Pablo Mercado 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Judy Baca, SPARC and A Chicana Mural Movement: Reconstructing U.S. History Through Public Art by Juan Pablo Mercado Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Juan Gómez-Quiñones, Chair This dissertation is about the uses and function of public art and makes the argument that public art should be viewed as an historical project. When developed within the framework of a collaborative community project with a thoughtful consideration to the experiences, values, and aspirations of community members, these projects challenge neocolonial tenets of exploitative labor conditions, racism, homophobia and sexism. By imagining public art as an innovative process that crosses the boundaries of social justice, history, and collective memory, Judith F. Baca established, and the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) employed a form of remembering that served as an essential component to understanding how communities envisioned themselves, their struggles, and their ability to transform history. Reimaging certain flashpoints in U.S. history through the historical projects of public murals urges a more nuanced consideration of the past that dislodges narratives of de jure and de facto discrimination and ii racial violence. What results from this reconsideration is a construction of multiple histories that challenge universally venerated, yet often distorted legacies of this nation. -

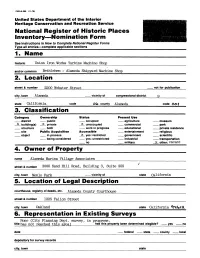

1. Name 6. Representation in Existing Surveys

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register off Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Union Iron Works Turbine Machine Shop and/or common Bethlehem - Alameda Shipyard Machine Shop 2. Location street & number 2200 Webster Street city, town Alameda vicinity of congressional district 9 state California code county Alameda code Oof 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private x unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process . x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military x other: vacant 4. Owner of Property name Alameda Marina Village Associates street & number 3000 Sand Hill Road, Building 3, Suite 255 city, town Menlo Park vicinity of state California 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Alameda County Courthouse street & number 1225 Fallen Street city, town Oakland state California 6. Representation in Existing Surveys None (City Planning Dept. survey, in progress, title has not reached this area)________has this property been determined elegible? yes no date . federal . state . county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered x original site _x_good __ruins _x_ altered __moved date __ fair? * __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance See Continuation Sheet - page 8. -

Regional Oral History Office University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Joyce Rutherford Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front Oral History Project This interview series was funded in part by a contract with the National Park Service, and with the support of individual donors. Interview conducted by Sam Redman in 2011 Copyright © 2016 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Joyce Rutherford, dated December 7, 2011. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.