Do Task Instructions Influence Readers' Topic Beliefs, Topic Belief Justifications, and Task Interest? a Mixed Methods Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

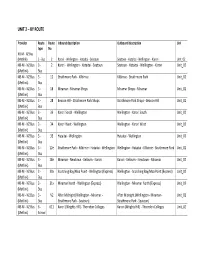

Unit 2 – by Route

UNIT 2 – BY ROUTE Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. NB -M - NZ Bus (Metlink) 3 - Bus 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12 Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18 Miramar - Miramar Shops Miramar Shops - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 28 Beacon Hill - Strathmore Park Shops Strathmore Park Shops - Beacon Hill Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 33 Karori South - Wellington Wellington - Karori South Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 34 Karori West - Wellington Wellington - Karori West Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 35 Hataitai - Wellington Hataitai - Wellington Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12e Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie - Hataitai - Wellington Wellington - Hataitai - Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18e Miramar - Newtown - Kelburn - Karori Karori - Kelburn - Newtown - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 30x Scorching Bay/Moa Point - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Scorching Bay/Moa Point (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 31x Miramar North - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Miramar North (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - N2 After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus Strathmore Park - Seatoun) Strathmore Park - Seatoun) NB-M - NZ Bus 6 - 611 Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Unit_02 (Metlink) School Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. -

Rongotai College

RONGOTAI COLLEGE PRINCIPAL’S NEWSLETTER Week 5, Term 2, 2018 COMING EVENTS Chem-Dry, had flowed into our short power outages Monday- basement classroom (A19), Wednesday this week as a result. We Monday 4 June basement corridor and storerooms, will phase turning heaters on before Queen’s Birthday holiday power switchboard and gas boilers school in the days ahead. and caused the problems we have Friday 8 June Rongotai Experience experienced. Classroom temperatures are now – no school for most students hovering between 12-17°, which while not ideal, does allow us to Tuesday 12 June keep the school open for instruction. Rongotai College Open Evening – no afternoon school for most students I certainly have appreciated the Wednesday 13 June goodwill of staff and students as St Patrick’s College Silverstream, sporting they are making do with this exchange at Silverstream situation. Thankfully, one of the gas Monday 18 June boilers is now working and it is Rongotai College Pasifika Parents’ Asosi at hoped the other will be by the end 6.30pm in the staffroom Water in A19 corridor of next week. Friday 22 June The water pipe was a relatively Winter Food Fair from 5.30pm in the Despite all of this, our boys seem to Renner Hall straightforward fix and electricity be coping well. For seniors, the into the school was reconnected on school year is more than one-third of Thursday 28 June Tuesday 22 May. It has taken about the way complete, and our deans, Board of Trustees’ meeting at 6pm in the a week for the basement to be dried Mackay Library academic mentors and classroom out. -

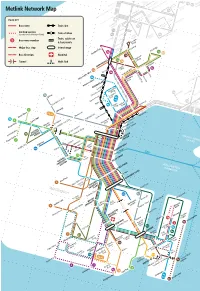

Metlink Network

1 A B 2 KAP IS Otaki Beach LA IT 70 N I D C Otaki Town 3 Waikanae Beach 77 Waikanae Golf Course Kennedy PNL Park Palmerston North A North Beach Shannon Waikanae Pool 1 Levin Woodlands D Manly Street Kena Kena Parklands Otaki Railway 71 7 7 7 5 Waitohu School ,7 72 Kotuku Park 7 Te Horo Paraparaumu Beach Peka Peka Freemans Road Paraparaumu College B 7 1 Golf Road 73 Mazengarb Road Raumati WAIKANAE Beach Kapiti E 7 2 Arawhata Village Road 2 C 74 MA Raumati Coastlands Kapiti Health 70 IS Otaki Beach LA N South Kapiti Centre A N College Kapiti Coast D Otaki Town PARAPARAUMU KAP IS I Metlink Network Map PPL LA TI Palmerston North N PNL D D Shannon F 77 Waikanae Beach Waikanae Golf Course Levin YOUR KEY Waitohu School Kennedy Paekakariki Park Waikanae Pool Otaki Railway ro 3 Woodlands Te Ho Freemans Road Bus route Parklands E 69 77 Muri North Beach 75 Titahi Bay ,77 Limited service Pikarere Street 68 Peka Peka (less than hourly, Monday to Friday) Titahi Bay Beach Pukerua Bay Kena Kena Titahi Bay Shops G Kotuku Park Gloaming Hill PPL Bus route number Manly Street71 72 WAIKANAE Paraparaumu College 7 Takapuwahia 1 Plimmerton Paraparaumu Major bus stop Train line Porirua Beach Mazengarb Road F 60 Golf Road Elsdon Mana Bus direction 73 Train station PAREMATA Arawhata Mega Centre Raumati Kapiti Road Beach 72 Kapiti Health 8 Village Train, cable car 6 8 Centre Tunnel 6 Kapiti Coast Porirua City Cultural Centre 9 6 5 6 7 & ferry route 6 H Coastlands Interchange Porirua City Centre 74 G Kapiti Police Raumati College PARAPARAUMU College Papakowhai South -

Prospectus for 2022

RONGOTAI COLLEGE PROSPECTUS Lumen accipe et imperti – Take the light and pass it on – Kapohia te ma-tauranga me ho- atu ra- RONGOTAI COLLEGE Lumen accipe et imperti Take the light and pass it on Kapohia te ma-tauranga me ho- atu ra- WELCOME TO RONGOTAI COLLEGE E nga- mana, e nga- waka, e nga- karangarangatanga o te motu, te-na koutou As parents and guardians of young males about to enter secondary education, you will want the best for your sons. Rongotai College has a proud tradition of achievement and excellence in academic, cultural and sporting activities. Rongotai College is a caring, supportive community, which is committed to helping every boy become the best he can be. It sets standards for boys to aspire to; it values tradition; it encourages excellence in all things; it recognises and celebrates the differences of our students; it provides opportunities for boys to expand their range of skills and abilities as they work through the process of realising their potential and becoming good men. We are proud of our college’s heritage and look forward to the future. I hope you will become a part of this future and experience something of the culture and spirit of this fine college. Nau mai haere mai. Kevin Carter, M.A.(Hons), Dip. Tchg. Principal WHY RONGOTAI COLLEGE? Rongotai College offers: • a roll size that allows every boy to be known and valued as an individual • a tradition of academic achievement and excellence • a top quality education for all students at all levels • a range of teaching programmes which meet the needs of all students • excellence in sporting and cultural activities • sound support for all students and fair, firm discipline • an experienced and highly-qualified teaching staff, made up of caring teachers who are involved in all areas of school life • opportunities and challenges for boys of all abilities and interests • a well-resourced school providing 21st century learning opportunities including BYOD. -

Lyall Bay/Rongotai HIGH FREQUENCY & PEAK ONLY ROUTES

Effective from 25 October 2020 Lyall Bay/Rongotai HIGH FREQUENCY & PEAK ONLY ROUTES 3 36 Wellington Station Massey University Wellington Hospital Thanks for travelling with Metlink. Kilbirnie Connect with Metlink for timetables Rongotai and information about bus, train and ferry services in the Wellington region. Lyall Bay metlink.org.nz 0800 801 700 [email protected] @metlinkwgtn /metlinkonourway Printed with mineral-oil-free, soy-based vegetable inks on paper produced using Forestry Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified mixed-source pulp that complies with environmentally responsible practices and principles. Please recycle and reuse if possible. Before taking a printed timetable, check our timetables online or use the Metlink commuter app. GW/PT-G-20/53 October 2020 T i n a d k a o o t r S R i i r R e o o k v a a a r in d Hill Stre g e T t l O Aitken S t u f M y LYALL BAY/RONGOTAIf a R u a Q m o p o Bo rl WELLINGTON w e en t Stre a 3 36 et W STATION B un ny St NORTHLAND Stout Street LAMBTON Glasgow Wharf Inter-Island Wharf Waterloo Wharf Featherston Street Wellington Panama St Cable Car Customhouse Quay d R a c n a m WELLINGTON a l a S CENTRAL Lambton Harbour G J l a e e d s r c R g v e a o r o r o r i G KELBURN w s e n to T Q l S r t e u e a r a Queens C h d e a d y a T r Ro e Pa t Wharf tal ien Chaffers Oriental Bay Or d C Marina T a a h o b e le R D S n Little Karaka Bay i C xo t o n re t S e r tr e f e t a et s r c e G n t ORIENTAL Balaena Bay Co BAY ARO VALLEY urt TE ARO ena ROSENEATH y P COURTENAY P lace Hawker St a t lli e -

Kilbirnie Community Emergency Hub Guide

REVIEWED JULY 2018 Kilbirnie Community Emergency Hub Guide This Hub is a place for the community to coordinate your efforts to help each other during and after a disaster. Objectives of the Community Emergency Hub are to: › Provide information so that your community knows how to help each other and stay safe. › Understand what is happening. Wellington Region › Solve problems using what your community has available. Emergency Managment Office › Provide a safe gathering place for members of the Logo Specificationscommunity to support one another. Single colour reproduction WELLINGTON REGION Whenever possible, the logo should be reproduced EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT in full colour. When producing the logo in one colour, OFFICE the Wellington Region Emergency Managment may be in either black or white. WELLINGTON REGION Community Emergency Hub Guide a EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE Colour reproduction It is preferred that the logo appear in it PMS colours. When this is not possible, the logo should be printed using the specified process colours. WELLINGTON REGION EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE PANTONE PMS 294 PMS Process Yellow WELLINGTON REGION EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE PROCESS C100%, M58%, Y0%, K21% C0%, M0%, Y100%, K0% Typeface and minimum size restrictions The typeface for the logo cannot be altered in any way. The minimum size for reproduction of the logo is 40mm wide. It is important that the proportions of 40mm the logo remain at all times. Provision of files All required logo files will be provided by WREMO. Available file formats include .eps, .jpeg and .png About this guide This guide provides information to help you set up and run the Community Emergency Hub. -

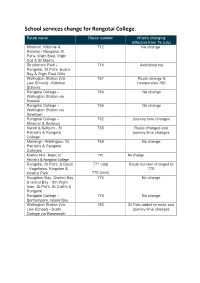

Rongotai-College New Bus Routes and Timetable

School services change for Rongotai College. Route name Route number What’s changing (effective from 15 July) Miramar, Kilbirnie & 712 No change Hataitai - Rongotai, St Pat's, Wgtn East, Wgtn Coll & St Mark's Strathmore Park - 714 Additional trip Rongotai, St Pat's, Evans Bay & Wgtn East Girls Wellington Station (Vic 751 Route change & Law School) - Kilbirnie incorporates 750 Schools Rongotai College - 754 No change Wellington Station via Hataitai Rongotai College - 755 No change Wellington Station via Newtown Rongotai College - 762 Journey time changes Miramar & Seatoun Karori & Kelburn - St 765 Route changed and Patrick's & Rongotai journey time changes College Mairangi - Wellington, St. 768 No change Patrick's & Rongotai Colleges Kowhai Park - Basin, St 770 No change Patrick's & Rongotai College Rongotai, St Pat's, & Basin 771 (old) Route number changed to - Vogeltown, Kingston & 770 Kowhai Park 770 (new) Houghton Bay, Owhiro Bay 774 No change & Island Bay - Sth Wgtn Inter, St Pat's, St Cath's & Rongotai Rongotai College - 776 No change Berhampore, Island Bay Wellington Station (Vic 782 St Pats added to route and Law School) - Scots journey time changes College via Roseneath Route 712 inbound Monday to Friday (excludes Public Holidays) Route bus stops Park Road (near 99) (school stop) 7247 7:50 AM Miramar North Road (near 57) 7246 7:51 AM Miramar North Road (near 103) 7245 7:52 AM Miramar North Road opposite David Farrington Park 7244 7:53 AM Darlington Road (near 188) 7242 7:55 AM Miramar - Darlington Road (near 124) 7241 7:57 AM Darlington -

Metlink School Bus Changes for Term 1, 2020

1 November 2019 J Laverock Scots College 1 Monorgan Road Strathmore Park Wellington Dear Jason RE: Metlink School Bus Changes for Term 1, 2020 This letter is to advise Scots College that there will be changes from Term 1, 2020 to public and designated school buses which your students currently use. These changes are aimed at improving the reliability and punctuality of bus services i.e. bus trips are more likely to run and to turn up on time, and the bus size better aligns with demand. We would like to acknowledge that under normal circumstances we would have consulted with you on the changes, particularly in relation to the designated school buses. Unfortunately, due to time constraints and operational needs we were unable to do so on this occasion. We have been working closely with NZ Bus to change bus timetables so they more accurately reflect actual time between the start and end of a trip. Part of this work has also involved assessing whether sufficient time has been provided for a bus to travel between the end location of one trip and the start location of the next trip. With the local and nation-wide bus driver shortages the extent of improvements that can be made have had to be balanced within the number of bus drivers and buses we have planned to have in January. This has meant we have had to makes sure we use the resource we do have available as efficiently as we can. To do this has involves the merging of some lower used school services (meaning some students may now need to stand), and replacing others with public service trips extended to schools during term times (ensures we retain a one bus journey for affected students). -

Rongotai College Parent and Caregiver Guide 2018

RONGOTAI COLLEGE PARENT AND CAREGIVER GUIDE 2018 RONGOTAI COLLEGE 170 Coutts St, PO Box 14-063 Kilbirnie, Wellington New Zealand Tel: + 64 4 939 3050 Fax: + 64 4 939 3060 Email: [email protected] February 2018 Dear Parents / Caregivers, Welcome to Rongotai College. This guide has been written to help you to understand the systems and procedures in place at Rongotai College. It is intended as a reference manual, to be used when you need to find information. Another excellent source of information about the operation of the school is the school website (www.rongotai.school.nz). You should make yourself fully conversant with our expectations and rules, so that your son will meet the requirements expected by the college. If you have any enquiries, please do not hesitate to contact me, Mr Simpson or Mr Tavernor (the Deputy Principals) through the college office (phone 939 3050). Kind regards Kevin Carter Principal SCHOOL MISSION, VISION AND VALUES E tū ki te kei o te waka, kia pākia koe e nga ngaru o te wā. Stand at the stern of the waka and feel the spray of the future on your face. MISSION STATEMENT Rongotai College is committed to developing young men of excellence, encouraging them to be the best that they can be in all areas of their lives. VISION Rongotai College will be an inclusive school reflecting its community and will encourage young men to solve problems, to think for themselves and to reach their full potential by providing a broad range of opportunities. VALUES Rongotai College values: These values been developed in consultation with the Board of Trustees, staff, students, parents and caregivers to focus and reflect on the core values of our school. -

Resource Consent Applications Recieved 14Th February – 28Th February 2021

Resource Consent applications recieved 14th February – 28th February 2021 You can sign up for a web alert at the bottom of Wellington.govt.nz to receive an email when this is updated. A Service Request (SR) number is the individual identification we give each Resource Consent application when lodged with Wellington City Council. If you contact us about any specific consent below, please quote this number. For More information on these consents please phone Customer Services on (04) 801 3590 or email Suburb Address Date SR No. Description Aro Valley 138 Raroa Road 22/02/2021 484609 Land Use: Conversion of existing garage/sleepout into new dwelling Brooklyn 5 Todman Street 26/02/2021 485007 Subdivision: Two lot fee simple (conversion from unit title) Churton Park 161 Amesbury Drive 17/02/2021 484241 Land Use: New dwelling Churton Park 85 Melksham Drive 19/02/2021 484475 Land Use: New dwelling Churton Park 156 Amesbury Drive 19/02/2021 484526 Land Use: Earthworks and terrace within a side yard Crofton Downs 9 Porokaiwhiri Street 1/03/2021 484611 Boundary Activity: New dwelling Horokiwi 539 Horokiwi Road 19/02/2021 484487 Right of Way Island Bay 24 Welland Place 3/03/2021 484221 Boundary Activity: Construction of carport Island Bay 142 Clyde Street 15/02/2021 484048 Land Use: Additions and alterations to existing dwelling Johnsonville 17 Meadowcroft Grove 18/02/2021 484456 Land Use: New detached garage Karaka Bays 50A Nevay Road 18/02/2021 484453 Land Use: Retrospective consent to relocate power pole Karori 367 Karori Road 17/02/2021 484239 -

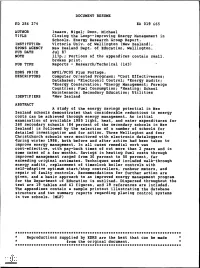

Closing the Loop--Improving Energy Management in Schools. Energy Research Group Report. INSTITUTION Victoria Univ

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 286 274 EA 019 665 AUTHOR Isaacs, Nigel; Donn, Michael TITLE Closing the Loop--Improving Energy Management in Schools. Energy Research Group Report. INSTITUTION Victoria Univ. of Wellington (New Zealand). SPONS AGENCY New Zealand Dept. of Education, Wellington. PUB DATE Jul 87 NOTE 117p.; Portions of the appendices contain small. broken print. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Computer Oriented Programs; *Cost Effectiveness; Databases; *Electronic Control; *Energy Audits; *Energy Conservation; *Energy Management; Foreign Countries; Fuel Consumption; *Heating; School Maintenance; Secondary Education; Utilities IDENTIFIERS *New Zealand ABSTRACT A study of the energy savings potential in New Zealand schools demonstrates that considerable reductions in energy costs can be achieved through energy management. An initial examination of available 1985 light, heat, and water expenditures for 268 secondary schools (84 percent of the secondary schools in New Zealand) is followed by the selection of a number of schools for detailed investigation and for action. Three Wellington and four Christchurch schools were monitored with electronic dataloggers during winter 1986, both before and after action had been taken to improve energy management. In all cases remedial work was cost-effective, with pay-back times of not more than 2 years and in some cases of a few months. Savings in heating fuel costs through improved management ranged from 30 percent to 50 percent, far exceeding original estimates. Techniques used included walk-through energy audits, replacement of timeclock boiler controls with self-adaptive optimum start/stop controllers, runhour meters, and repair of faulty controls. Recommendations for further action are given, and a basic approach to an improved energy management program for the Department of Education is outlined. -

Karori - Allington Road →Miramar - Darlington Road View in Website Mode (Near 155)

2 bus time schedule & line map 2 Karori - Allington Road →Miramar - Darlington Road View In Website Mode (Near 155) The 2 bus line (Karori - Allington Road →Miramar - Darlington Road (Near 155)) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Karori - Allington Road →Miramar - Darlington Road (Near 155): 5:30 AM - 11:28 PM (2) Karori - Allington Road →Seatoun Park - Hector Street: 5:45 AM - 11:13 PM (3) Kilbirnie - Stop B →Lambton Quay North - Stop C: 6:44 AM - 8:22 AM (4) Miramar - Darlington Road (Near 124) →Karori - Karori Road: 5:24 AM - 11:14 PM (5) Seatoun Park - Hector Street →Karori - Karori Road: 5:37 AM - 7:01 PM (6) Seatoun Village - Dundas Street →Karori - Karori Road: 7:16 PM - 11:28 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 2 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 2 bus arriving. Direction: Karori - Allington Road →Miramar - 2 bus Time Schedule Darlington Road (Near 155) Karori - Allington Road →Miramar - Darlington Road 53 stops (Near 155) Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Karori - Allington Road 2 South Karori Road, Wellington Tuesday Not Operational Karori Park Pavilion - Karori Road Wednesday 5:30 AM - 11:28 PM 393 Karori Road, Wellington Thursday 5:30 AM - 11:28 PM Karori Road at Tringham Street Friday 5:30 AM - 11:28 PM 354 Karori Road, Wellington Saturday 6:10 AM - 11:15 PM Karori Road Opposite Richmond Avenue 338A Karori Road, Wellington Karori Road Opposite St Teresa's School 292 Karori Road, Wellington 2 bus Info Direction: Karori - Allington