Rongotai – Hue Te Taka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No 87, 17 September 1942, 2371

JlumlJ. 87. 2371 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 1942. Land proclaimed as Road, and Road closed, in Block I, Tutaki Survey District, Murchison County. [L.S,] C. L. N. NEWALL, Governor-General. A PROCLAMATION. N pursuance and exercise of the powers conferred by section twelve of the Land Act, 1924, I, Cyril Louis Norton Newall, the Governor I General of the Dominion of New Zealand, do hereby proclaim as road the land described in the First Schedule hereto; and also do hereby proclaim as closed the road described in the Second Schedule hereto. FIRST SCHEDULE. LAND PROCLAIMED AS ROAD. Approxi:qrate Areas I of the Pieces of Land Being Shown on Plan Coloured on proclaimed as Road. Plan I A. R P. 0 2 4 Part Section 91, Square 138 (Ferry Reserve) P.W.D. 112244 Yellow. 0 2 20 Part Section 91, Square 138 (Ferry Reserve) 0 0 0·3. Part Section 55 (Ferry Reserve) .. (S.O. 9255.) 0 1 6 Part Section 97 P.W.D. 108877 Yellow. 0 3 27 Part Section 61, Square 170 Blul'. 0 2 17 Part Section 61, Square 170 0 1 29 Part Section 61, Square 170 0 0 15 River-bed adjoining Section 61, Square 170 0 0 16 Part Section 61, Square 170 (Scenic Reserve) 0 0 23 Part Section 61, Square 170 (Scenic Reserve) (S.O. 9069.) (Nelson R.D.) I SECOND SCHEDULE. ROAD CLOSED. Approximate Areas I Adjoining or passing through Coloured on of the Pieces of Road Shown on Plan Plan closed. I A, R. -

TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA HERITAGE TRAIL MAIN FEATURES of the TRAIL: This Trail Will Take About Four Hours to Drive and View at an Easy TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA Pace

WELLINGTON’S TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA HERITAGE TRAIL MAIN FEATURES OF THE TRAIL: This trail will take about four hours to drive and view at an easy TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA pace. Vantage points are mostly accessible by wheelchair but there are steps at some sites such as Rangitatau and Uruhau pa. A Pou (carved post), a rock or an information panel mark various sites on the trail. These sites have been identified with a symbol. While the trail participants will appreciate that many of the traditional sites occupied by Maori in the past have either been built over or destroyed, but they still have a strong spiritual presence. There are several more modern Maori buildings such as Pipitea Marae and Tapu Te Ranga Marae, to give trail participants a selection of Maori sites through different periods of history. ABOUT THE TRAIL: The trail starts at the Pipitea Marae in Thorndon Quay, opposite the Railway Station, and finishes at Owhiro Bay on the often wild, southern coast of Wellington. While not all the old pa, kainga, cultivation and burial sites of Wellington have been included in this trail, those that are have been selected for their accessibility to the public, and their viewing interest. Rock Pou Information panel Alexander Turnbull Library The Wellington City Council is grateful for the significant contribution made by the original heritage Trails comittee to the development of this trail — Oroya Day, Sallie Hill, Ken Scadden and Con Flinkenberg. Historical research: Matene Love, Miria Pomare, Roger Whelan Author: Matene Love This trail was developed as a joint project between Wellingtion City Council, the Wellington Tenths Trust and Ngati Toa. -

How to Kill Rats and Engage a Community

HOW TO KILL RATS AND ENGAGE A COMMUNITY INTRODUCTION Predator Free Miramar is a volunteer community project, established in winter 2017 to rid Wellington’s Miramar Peninsula of rats, stoats and weasels, and bring back the birds and the bush to the eastern suburbs. Over the last three years we’ve created a community of backyard trappers, by asking people to install a trap in their backyards, keep it baited, and report their catches. Simple. The initial target was to have a rat trap in one out of every five backyards, effectively a trap every 50 metres, which is thought to be roughly the home range of a rat. There are about 7500 households on the peninsula, which means we needed 1500 backyards traps to meet the target. As we approach Christmas 2019, we have 1448 traps out, and Predator Free Wellington’s eradication operation is almost complete. As a community working together, in two and a half years, we’ve removed more than ten thousand rats, mice, hedgehogs and weasels from the Miramar landscape. My hugely supportive wife Jess is able to access our deep freezer again, now that my stash of frozen ‘sample’ rats and weasels have been cleared, and the months of deferred maintenance in our own backyard might just get a look in, now that I don’t have quite so many trapping missions to complete. So what follows is a reflection on how we got here. Despite the title, this is not an instruction manual on how another group should proceed; what makes these projects so great is that there’s no one way of doing it. -

Elegant Report

C U L T U R A L IMPACT R E P O R T Wellington Airport Limited – South Runway extension Rongotai – Hue te Taka IN ASSOCIATION WITH PORT NICHOLSON BLOCK SETTLEMENT TRUST, WELLINGTON TENTHS TRUST AND TE ATIAWA KI TE UPOKO O TE IKA A MAUI POTIKI TRUST (MIO) OCTOBER 2015 CULTURAL IMPACT REPORT Wellington Airport – South Runway extension RONGOTAI – HUE TE TAKA TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................................3 THE PROJECT .............................................................................................................................................4 KEY MAORI VALUES ASSOCIATED WITH THIS AREA ..................................................................6 FISHING AND FISHERIES IN THE AREA ...........................................................................................................8 MARINE FLORA .......................................................................................................................................... 10 BLACK-BACKED GULLS ............................................................................................................................. 10 WATER QUALITY........................................................................................................................................ 11 Consultation .......................................................................................................................................... 12 RECREATION USE OF THE -

Te Motu Kairangi Miramar Peninsula Draft Prospectus

TE MOTU KAIRANGI MIRAMAR PENINSULA A PROSPECTUS OF OPPORTUNITIES DOCUMENT PREPARED BY BOFFA MISKELL FOR WELLINGTON CITY COUNCIL DECEMBER 2016 What are we looking for? GIVE US 2 YEARS TO MAKE A PLAN WITH YOU Wellington City Council (WCC) is looking for a commitment from central government to partner with it, iwi and stakeholders - regional government, private enterprise and the community - to work together to agree a holistic plan that can optimise the benefits on offer for all the interests at Te Motu Kairangi/ Miramar Peninsula. The opportunity is now, before firm committments have been made about all the large areas of government land. It is time to seize the day - lets create a plan for Te Motu Kairangi/Miramar Peninsula by bringing all the interests together. The process to make the plan allows mutual benefits to be discovered. WCC will resource the 2 year plan making process. If we join together the sum of the parts can be greater than the whole. THE + +++ + = MIRAMAR PLAN TE MOTU KAIRANGI/MIRAMAR PENINSULA PLAN 3 2ND DRAFT 05.12.2016 What are we looking for? Public Ownership (Other) GIVE US 2 YEARS TO MAKE A PLAN WITH YOU Port Nicholson Settlement Block Trust (PNSBT) We are looking for a 2 year commitment that central government land (Land Information New Zealand, Her Majesty the Queen Ministry of Defence, Housing New Zealand, Ministry of Education, Airways Corporation, NIWA, Ministry of Culture and Heritage, Department of Corrections and Department of Conservation) can be Wellington City Council openly considered as part of the Miramar opportunity. Many of the once government facilities are now redundant. -

INFO EXPRESS Y7-9 Term 4 Week 1 17 October - 23 October 2011

INFO EXPRESS Y7-9 Term 4 Week 1 17 October - 23 October 2011 Virtue: Enthusiasm Enthusiasm is being cheerful, happy, and full of spirit. It is Please check the entry page for doing something wholeheartedly and eagerly. When you attachments related to: are enthusiastic, you have a positive attitude. Enthusiasm Victoria University, Public lecture. is being inspired. House Music DVD. Y7 Vision Testing Dates to note Monday 17 October Regional Public Health provides a vision screening Staff only day. programme at school during Year 7 and this will take place Tuesday 18 October at Marsden on Thursday 29 September. Pupils will be Term 4 begins (full summer or full advised of results at the time of testing. If further winter uniform may be worn this assessment is recommended you will be notified by mail. week but uniforms may not be Children who wear glasses and/or are under professional mixed). care and have regular checks will not require a vision Thursday 20 October check by this service. Please notify the school nurses 7.30pm Old Girls’ Association Nadine Smith ( [email protected] ) and meeting , Swainson Room. Sally Allen ( [email protected] ) if you DO NOT agree to your daughter being screened. Monday 24 October Please note that this screening test is not a full assessment Labour Day – School closed. of your daughter’s vision. If you have any concerns, please Tuesday 25 October consult an optometrist. Summer Uniform only from today. Y7/8 Life Education at school until House Music DVD: orders due Friday 21 October Friday. -

Brooklyn-Tattler-May-2017

MAY 2017 287 BROOKLYN TATTLER what’s happening in your community Brooklyn Scouts What’s On Winter Health Community News From the Library Brooklyn History Community Groups A five week course for parents starts on IN THIS ISSUE from the Tuesdays in the Brooklyn Community Centre’s RSA room from 10am to 12pm. Coordinator/BCA 2-3 BCA News coordinatOr The course is called your parenting act. From the Councillor 4 EUAN HARRis ACT is short for Acceptance and A longstanding member of our Brooklyn Scouts 5 brooklyn cOmmunity centre & Commitment Therapy. For more info community, Dave Fowler vOgelmOrn hall ph 384 6799 contact Amanda Jack on 021 0291 4453 or died suddenly in late April. History 6 [email protected] Residents’ Association 7 email: [email protected] Hi Everyone, Our condolences to Barbara, their Health News 8 On Fridays from 11:30am in the main hall, two children and wider family. From the Library 9 Old hall gigs We have just ended a special dance classes for 3 and 4 year olds busy month at Brooklyn Community What’s On 10-11 will run for 30 minute sessions. Called For those who knew Dave, a ‘Book Centre and Vogelmorn Hall. The special rocking popping bods, each session of Memories’ is available in the foyer Resource Centre News 12 music only evening concert hosted by aims to create a cool music motion class for of the Brooklyn Community Centre, Friends of Owhiro Stream 14 Old Hall Gigs at Vogelmorn Hall on preschoolers and their parents by rocking 18 Harrison St, to write stories Upstream 15 Saturday 22 April sold out quickly to a routines to pop tunes. -

Unit 2 – by Route

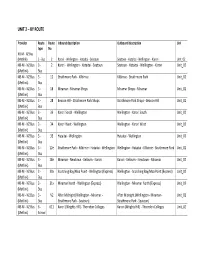

UNIT 2 – BY ROUTE Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. NB -M - NZ Bus (Metlink) 3 - Bus 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12 Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18 Miramar - Miramar Shops Miramar Shops - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 28 Beacon Hill - Strathmore Park Shops Strathmore Park Shops - Beacon Hill Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 33 Karori South - Wellington Wellington - Karori South Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 34 Karori West - Wellington Wellington - Karori West Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 35 Hataitai - Wellington Hataitai - Wellington Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12e Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie - Hataitai - Wellington Wellington - Hataitai - Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18e Miramar - Newtown - Kelburn - Karori Karori - Kelburn - Newtown - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 30x Scorching Bay/Moa Point - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Scorching Bay/Moa Point (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 31x Miramar North - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Miramar North (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - N2 After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus Strathmore Park - Seatoun) Strathmore Park - Seatoun) NB-M - NZ Bus 6 - 611 Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Unit_02 (Metlink) School Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. -

Rongotai College

RONGOTAI COLLEGE PRINCIPAL’S NEWSLETTER Week 5, Term 2, 2018 COMING EVENTS Chem-Dry, had flowed into our short power outages Monday- basement classroom (A19), Wednesday this week as a result. We Monday 4 June basement corridor and storerooms, will phase turning heaters on before Queen’s Birthday holiday power switchboard and gas boilers school in the days ahead. and caused the problems we have Friday 8 June Rongotai Experience experienced. Classroom temperatures are now – no school for most students hovering between 12-17°, which while not ideal, does allow us to Tuesday 12 June keep the school open for instruction. Rongotai College Open Evening – no afternoon school for most students I certainly have appreciated the Wednesday 13 June goodwill of staff and students as St Patrick’s College Silverstream, sporting they are making do with this exchange at Silverstream situation. Thankfully, one of the gas Monday 18 June boilers is now working and it is Rongotai College Pasifika Parents’ Asosi at hoped the other will be by the end 6.30pm in the staffroom Water in A19 corridor of next week. Friday 22 June The water pipe was a relatively Winter Food Fair from 5.30pm in the Despite all of this, our boys seem to Renner Hall straightforward fix and electricity be coping well. For seniors, the into the school was reconnected on school year is more than one-third of Thursday 28 June Tuesday 22 May. It has taken about the way complete, and our deans, Board of Trustees’ meeting at 6pm in the a week for the basement to be dried Mackay Library academic mentors and classroom out. -

Wellington Walks – Ara Rēhia O Pōneke Is Your Guide to Some of the Short Walks, Loop Walks and Walkways in Our City

Detail map: Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori Hill) Detail map: Mount Victoria (Matairangi) Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. Tracks are good quality but can be steep in places. ade North North Wellington Otari-Wilton’ss BushBush OrientalOriental ParadePar W ADESTOWN WeldWeld Street Street Wade Street Oriental Bay Walks Grass St. WILTON Oriental Parade O RIEN T A L B A Y Ara Rēhia o Pōneke Northern Walkway PalliserPalliser Rd.Rd. Skyline Walkway To City ROSENEATH Majoribanks Street City to Sea Walkway LookoutLookout Rd.Rd. Te Ara o Ngā Tūpuna Mount Victoria Lookout MOUNT (Tangi(Tangi TeTe Keo)Keo) Te Ahumairangi Hill GrantGrant RoadRoad VICT ORIA Lookout PoplarPoplar GGroroveve PiriePirie St.St. THORNDON AlexandraAlexandra RoadRoad Hobbit Hideaway The Beehive Film Location TinakoriTinakori RoadRoad & ParliameParliamentnt rangi Kaupapa RoadStSt Mary’sMary’s StreetStreet OOrangi Kaupapa Road buildingsbuildings WaitoaWaitoa Rd.Rd. HataitaiHataitai RoadHRoadATAITAI Welellingtonlington BotanicBotanic GardenGarden A B Southern Walkway Loop walks City to Sea Walkway Matairangi Nature Trail Lookout Walkway Northern Walkway Other tracks Southern Walkway Hataitai to City Walkway 00 130130 260260 520520 Te Ahumairangi metresmetres Be prepared For more information Your safety is your responsibility. Before you go, Find our handy webmap to navigate on your mobile at remember these five simple rules: wcc.govt.nz/trailmaps. This map is available in English and Te Reo Māori. 1. Plan your trip. Our tracks are clearly marked but it’s a good idea to check our website for maps and track details. Find detailed track descriptions, maps and the Welly Walks app at wcc.govt.nz/walks 2. Tell someone where you’re going. -

Golden Mile Engagement Report June

GOLDEN MILE Engagement summary report June – August 2020 Executive Summary Across the three concepts, the level of change could be relatively small or could completely transform the road and footpath space. The Golden Mile, running along Lambton Quay, Willis Street, Manners Street and 1. “Streamline” takes some general traffic off the Golden Mile to help Courtenay Place, is Wellington’s prime employment, shopping and entertainment make buses more reliable and creates new space for pedestrians. destination. 2. “Prioritise” goes further by removing all general traffic and allocating extra space for bus lanes and pedestrians. It is the city’s busiest pedestrian area and is the main bus corridor; with most of the 3. “Transform” changes the road layout to increase pedestrian space city’s core bus routes passing along all or part of the Golden Mile everyday. Over the (75% more), new bus lanes and, in some places, dedicated areas for people next 30 years the population is forecast to grow by 15% and demand for travel to and on bikes and scooters. from the city centre by public transport is expected to grow by between 35% and 50%. What we asked The Golden Mile Project From June to August 2020 we asked Wellingtonians to let us know what that they liked or didn’t like about each concept and why. We also asked people to tell us The Golden Mile project is part of the Let’s Get Wellington Moving programme. The which concept they preferred for the different sections of the Golden Mile, as we vision for the project is “connecting people across the central city with a reliable understand that each street that makes up the Golden Mile is different, and a public transport system that is in balance with an attractive pedestrian environment”. -

Appendix 13 Shelly Bay Cultural Impact Statement

CULTURAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT WHĀTAITAI, MARUKAIKURU, SHELLY BAY Taikuru Prepared by Kura Moeahu, Peter Adds and Lee Rauhina-August on behalf of Taranaki Whānui Ki Te Upoko o Te Ika and The Port Nicholson Block Settlement Trust, September 2016 STATUS: FINAL 1 Executive Summary This is a Cultural Impact Assessment Report for Shelly Bay/Marukaikuru commissioned by the Wellington Company Limited. It assesses the Māori cultural values of Marukaikuru Bay from the perspective of the tangata whenua, namely the iwi of Taranaki Whānui represented by the PNBST. The main findings of this cultural impact assessment are: • Marukaikuru Bay has high cultural significance to the iwi of Taranaki whanui • Taranaki Whānui people actually lived in the Bay until 1835 • We have found no evidence of other iwi connections to Marukaikuru Bay • Taranaki Whānui mana whenua status in relation to Marukaikuru and the Wellington Harbour is strongly supported in the literature, including the Waitangi Tribunal report (2003) • The purchase of Shelly Bay by PNBST from the Crown was a highly significant Treaty settlement transaction specifically for the purpose of future development • Any development of Marukaikuru must adequately take account of and reflect Taranaki Whānui cultural links, history and tangata whenua status in Wellington. • Taranaki Whānui have kaitiakitanga (guardianship) responsibilities to ensure the protection of the natural, historical and cultural dimensions of Marukaikuru. • The resource consent application submitted by the Wellington Company Limited is supported by the Port Nicholson Block Settlement Trust. 2 WHĀTAITAI, MARUKAIKURU, SHELLY BAY Taikuru Kapakapa kau ana te manu muramura ki te tai whakarunga Māwewe tonu ana te motu whāriki o te tai whakararo Makuru tini e hua ki whakatupua-nuku Matuatua rahi e hua ki whakatupua-ruheruhe Pukahu mano e hua ki whakatupua-rangi Inā te tai hekenga ki runga o Tai Kuru e..