East River Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

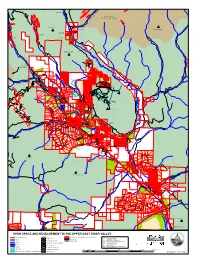

OPEN SPACE and DEVELOPMENT in the UPPER EAST RIVER VALLEY Open Space Subdivided Land & Single Family Residences Parcel Boundaries C.C

K E TO SCHOFIELD E R C R E MAROON BELLS P P SNOWMASS WILDERNESS O C GOTHIC MOUNTAIN GOTHIC TOWNSITE TEOCALLI MOUNTAIN (RMBL) Gothic Mountain Subdivision Washington Gulch (CBLT) Glee Biery C.E. Maxfield Meadows C.E. The Bench (CBLT) (CBLT) C.E. (CBLT) Rhea Easement C O U N T SNODGRASS MOUNTAIN Y 3 1 7 W E A A S S S L H T A IN T G R E T IV O E R N R I V G E U L R C The Reserve (C.E.) H R (COL) D RAGGEDS WILDERNESS Smith Hill #1 (CBLT) Divine C.E. (CBLT) Meridian Lake Park D R C I M H E T R MERIDIAN LAKE PARK O I G Gunsight D RESERVOIR I Bridge A Prospect C.A. N K Parcel CREE FUL (CBLT) L -JOY A H-BE K O E TOWN OF \( L MT. CRESTED BUTTE BLM O W N A NICHOLSON LAKE G S H L I A N K BLM G Smith Hill RanEches T ) O N Alpine Meadows C.A. G Glacier Lily U Donation L (CBLT) C Nevada C.E. H Lower Loop (CBLT) Parcels R Rolling River C.E. (CBLT) (CBLT) D Wildbird C.O. Investments Glacier Lily Estates Estates (CBLT) BLM Rice Parcel (CBLT) Peanut Mine C.E. (TCB) MT EMMONS Utley Parcel S LA (CBLT) TE Peanut Lake R Saddle Ridge C.A. Parcel (CBLT) IV ER PEANUT LAKE Gallin Parcel (CBLT) R CRESTED BUTTE D Robinson Parcel Three (CBLT) Trappers Crossing S Valleys L Kapushion Family P Confluence at C.B. -

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Locatable Mineral Reports for Colorado, South Dakota, and Wyoming provided to the U.S. Forest Service in Fiscal Years 1996 and 1997 by Anna B. Wilson Open File Report OF 97-535 1997 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1 COLORADO ...................................................................... 2 Arapaho National Forest (administered by White River National Forest) Slate Creek .................................................................. 3 Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests Winter Park Properties (Raintree) ............................................... 15 Gunnison and White River National Forests Mountain Coal Company ...................................................... 17 Pike National Forest Land Use Resource Center .................................................... 28 Pike and San Isabel National Forests Shepard and Associates ....................................................... 36 Roosevelt National Forest Larry and Vi Carpenter ....................................................... 52 Routt National Forest Smith Rancho ............................................................... 55 San Juan National -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests DRAFT Wilderness Evaluation Report August 2018 Designated in the original Wilderness Act of 1964, the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness covers more than 183,000 acres spanning the Gunnison and White River National Forests. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

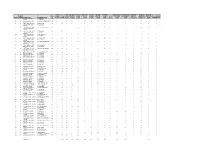

Region Forest Number Forest Name Wilderness Name Wild

WILD FIRE INVASIVE AIR QUALITY EDUCATION OPP FOR REC SITE OUTFITTER ADEQUATE PLAN INFORMATION IM UPWARD IM NEEDS BASELINE FOREST WILD MANAGED TOTAL PLANS PLANTS VALUES PLANS SOLITUDE INVENTORY GUIDE NO OG STANDARDS MANAGEMENT REP DATA ASSESSMNT WORKFORCE IM VOLUNTEERS REGION NUMBER FOREST NAME WILDERNESS NAME ID TO STD? SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE SCORE FLAG SCORE SCORE COMPL FLAG COMPL FLAG SCORE USED EFF FLAG 02 02 BIGHORN NATIONAL CLOUD PEAK 080 Y 76 8 10 10 6 4 8 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST WILDERNESS 02 03 BLACK HILLS NATIONAL BLACK ELK WILDERNESS 172 Y 84 10 10 4 10 10 10 10 N 8 8 Y N 4 N FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP FOSSIL RIDGE 416 N 59 6 5 2 6 8 8 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LA GARITA WILDERNESS 032 Y 61 6 3 10 4 6 8 8 N 6 6 Y N 4 Y GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP LIZARD HEAD 040 N 47 6 3 2 4 6 4 6 N 6 8 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP MOUNT SNEFFELS 167 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP POWDERHORN 413 Y 62 6 6 2 6 8 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP RAGGEDS WILDERNESS 170 Y 62 0 6 10 6 6 10 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP UNCOMPAHGRE 037 N 45 6 5 2 2 6 4 8 N 4 6 Y N 2 N GUNNISON NATIONAL WILDERNESS FOREST 02 04 GRAND MESA UNCOMP WEST ELK WILDERNESS 039 N 56 0 6 10 6 6 4 10 N 6 8 Y N 0 N GUNNISON NATIONAL FOREST 02 06 MEDICINE BOW-ROUTT ENCAMPMENT RIVER 327 N 54 10 6 2 6 6 8 6 -

10#Marcellina#Lane#–#Lot#2#Marcellina#Centre

10#MARCELLINA#LANE#–#LOT#2#MARCELLINA#CENTRE# CHRIS KOPF PREVIEWS® PROPERTY SPECIALIST COLDWELL BANKER BIGHORN REALTY cell: 970.209.5405 [email protected] www.chriskopf.com 10#MARCELLINA#LANE#–#LOT#2#MARCELLINA#CENTRE# INTRODUCTION Coldwell Banker Bighorn Realty and Chris Kopf, Previews® Property Specialist are pleased to offer qualified investors the opportunity to acquire the recently subdivided parcel of land located at 10 Marcellina Lane. This 1.96-acre, high-density multi-family development site is located in Mt. Crested Butte, Colorado, a popular year-round recreation area located southwest of Denver, Colorado. This location provides residents with easy access to Crested Butte Mountain Resort (<1/2 mile). Crested Butte Mountain Resort provides over 1,100 acres of skiing during the winter months and numerous recreational activities in the summertime. Additionally, the property is located just minutes from numerous shopping, dining, and limitless recreational opportunities. MLS # 37621. Offered at $379,000. HIGHLIGHTS • Convenient bus service is available with a bus stop located immediately adjacent to the property. The Crested Butte Mountain Express (MX) provides free public ground transportation services for residents of and visitors to Mt. Crested Butte, Crested Butte, and the surrounding north valley communities. The RTA Bus provides free public ground transportation to Gunnison – approx. 2,000 feet away at Mt. CB Base Area Transit Center. • The future development opportunity of this 85,372 square foot parcel allows for up to 51,223 square feet of High Density Multiple Family development, and up to a maximum of 96 units. • The Gunnison-Crested Butte Regional Airport (GUC) is located in the city of Gunnison, just 28 miles from the town of Crested Butte and 31 miles from the town of Mt. -

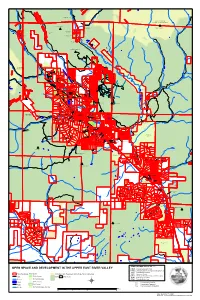

Open Space and Development in The

K TO SCHOFIELD E E R C R MAROON BELLS E SNOWMASS WILDERNESS P P O GOTHIC MOUNTAIN C GOTHIC TOWNSITE TEOCALLI MOUNTAIN (RMBL) Stroh Parcels Gothic Mountain (CBLT) Subdivision Washington Gulch (CBLT) Glee Biery C.E. Maxfield Meadows C.E. The Bench (CBLT) (CBLT) C.E. (CBLT) Rhea Easement Trampe Ranch (RMBL) (TPL) HE No.267 (RMBL) C O U N T SNODGRASS MOUNTAIN Y 3 1 7 W E A A S S S L H T A I T N R Trampe Ranch G I E T V (TPL) O E R N R I V G E U L Promontory R C H Ranch C.E. R D (CBLT) Smith Hill C.E. (CBLT) RAGGEDS Meridian Lake Park WILDERNESS Kochevar Parcel D (CBLT) R Coralhouse C.E. Kochevar C (TCB) I Parcel H Phase II M T (CBLT) E MERIDIAN LAKE PARK O G Gunsight ( R RESERVOIR L I Bridge O D Prospect C.A. I K Parcel N A REE G UL C (TCB) N JOYF BE- Slate River L L Crested Butte H- A A O Trailhead K TOWN OF K Ski Ranches (CBLT) E E ) MT. CRESTED BUTTE BLM W A NICHOLSON S H LAKE I N BLM G T Smith Hill Ranches O Kochevar N Alpine Meadows C.A. Parcel G Phase III U Glacier Lily Trampe Ranch (CBLT) L (CBLT) C Nevada C.E. (TPL) Lower Loop Parcels H (CBLT) (TCB) R Slate River #1 (CBLT) Glacier Lily D Wildbird Slate River #2 (CBLT) Estates Budd Trail Estates Kochevar Parcel Easement (CBLT) (CBLT) BLM Peanut Mine (TCB) Rice Parcel MT EMMONS Utley Parcel S Peanut Lake LA (TCB) TE Parcel (TCB) R Saddle Ridge C.A. -

Gunnison County Begins COVID-19 Vaccinations Priorities Outlined but Process Will Take Several Months

NEWS | COMMUNITY | SPORTS | CULTURE | OPINION D BU ESTE TTE R NE E C W H S T ’ CrCrestedested ButtButtee NNewsews See page 25 the News never sleeps | www.crestedbuttenews.com VOL.60 | NO.51 | DECEMBER 18, 2020 | 50¢ Gunnison County begins COVID-19 vaccinations Priorities outlined but process will take several months [ BY MARK REAMAN ] Two local doctors and a resident of the Gunnison County Senior Care Center were slated to be the first to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in Gunnison County late Wednesday afternoon at the Fred Field Western Heritage Center at the county fairgrounds. Dr. Lor-Anne Gibans, geriatric physician for the nursing home residents; Dr. Shay Krier, Emergency Department physician and medi- cal director of EMS, who also won the Colo- rado EMS director award for 2020; and Lucy Hudgeons, a resident at the Senior Care Cent- IT’S HERE!: Gunnison County Coronavirus Team Incident Commander C.J. Malcolm took possession of the first 300 doses of the er, were the first to roll up their sleeves and COVID-19 vaccine that arrived Tuesday afternoon. The first shots were scheduled to start Wednesday. photo by Nolan Blunck receive the first of two injections of the newly approved vaccine. They will each have to get a second dose in three weeks. “These are some of the highest risk and Local man Gunnison Country Food Pantry frontline folks dealing with the coronavirus,” explained Gunnison County public informa- injured in an ramps up efforts to feed the valley tion officer Andrew Sandstrom. “Part of the reason they were selected to be the first ones in the county to get the vaccine is to show it is “It’s neighbors helping cent, with 1,425 households asking for safe and set an example for the community.” avalanche on help. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

Geology and Slope Stability of Crestone, CO Snodgrass Mountain Ski Area March 2008 Crested Butte, CO CHAPTER 2-- GEOLOGY

GEO-HAZ Consulting, Inc. Geology and Slope Stability of Crestone, CO Snodgrass Mountain Ski Area March 2008 Crested Butte, CO CHAPTER 2-- GEOLOGY This chapter describes the bedrock and Quaternary geology of Snodgrass Mountain, with special emphasis of landslides. Because the area had been mapped several times before, our first task was to compare the various maps. 2.1 Methods 2.1.1 Digitizing previous landslide mapping During the winter of 2006-2007 we digitized the landslide mapping from all seven previous landslide studies (Table 2-1). These maps were georeferenced by International Alpine Design, Vail, CO, for use in our GIS, so we could visually compare the various maps. Table 2-1. Previous studies in which landslides were mapped on Snodgrass Mountain. Author Date Title Map Remarks and Digitizing Scale Gaskill et al. 1967 Geologic map of the 1:24,000 Published USGS color map; being Oh-Be-Joyful digitized by IAD quadrangle… Soule 1976 Geologic Hazards in Ca. Polygons identical to those in the Crested Butte- 1:43,000 Gaskill. Gunnison Area (9 quads) Gaskill et al. 1991 Geologic map of the 1:24,000 Published USGS color map; see Gothic quadrangle… DIGITAL APPENDIX D2.1 on DVD- ROM only Resource 1995 Geologic Hazard 1:6,000 Includes several large landslide Consultants Assessment and deposits, and many small scarps; and Mitigation Planning for digitized by Pioneer Environmental Engineers Crested Butte Mountain in 1995 (RCE) Resort Irish 1996 Geologic Hazard Study 1:12,000 Concludes that Chicken Bone, Zones 3-A and 3-B Slump Block, and toe -

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN a HANDBOOK for INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14

THE GUNNISON RIVER BASIN A HANDBOOK FOR INHABITANTS from the Gunnison Basin Roundtable 2013-14 hen someone says ‘water problems,’ do you tend to say, ‘Oh, that’s too complicated; I’ll leave that to the experts’? Members of the Gunnison Basin WRoundtable - citizens like you - say you can no longer afford that excuse. Colorado is launching into a multi-generational water planning process; this is a challenge with many technical aspects, but the heart of it is a ‘problem in democracy’: given the primacy of water to all life, will we help shape our own future? Those of us who love our Gunnison River Basin - the river that runs through us all - need to give this our attention. Please read on.... Photo by Luke Reschke 1 -- George Sibley, Handbook Editor People are going to continue to move to Colorado - demographers project between 3 and 5 million new people by 2050, a 60 to 100 percent increase over today’s population. They will all need water, in a state whose water resources are already stressed. So the governor this year has asked for a State Water Plan. Virtually all of the new people will move into existing urban and suburban Projected Growth areas and adjacent new developments - by River Basins and four-fifths of them are expected to <DPSDYampa-White %DVLQ Basin move to the “Front Range” metropolis Southwest Basin now stretching almost unbroken from 6RXWKZHVW %DVLQ South Platte Basin Fort Collins through the Denver region 6RXWK 3ODWWH %DVLQ Rio Grande Basin to Pueblo, along the base of the moun- 5LR *UDQGH %DVLQ tains. -

The Collegiate Range Project July 1986

THE COLLEGIATE RANGE PROJECT JULY 1986 I. Introduction The Gunnison River Basin has long been considered one of the finest water resources in the State of Colorado. To date, development of this resource has been undertaken by the United States government. The primary purposes of this development have been to regulate streamflow for: 1) hydropower generation for Colorado River Storage Project participants and 2) diversion to the Uncompahgre River Basin for agricultural uses. The City of Aurora has applied for conditional water rights on tributaries to the Gunnison River for a water supply development entitled the "Collegiate Range Project." The plans for this project were initially prepared by Marvin J. Greer, the general partner for Sierra Madre Lode, Ltd. Mr. Greer is a retired engineer formerly with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The City of Aurora has reviewed these plans as well as other Gunnison River water supply reports. 1) "Water and Related Land Resources, Gunnison River Basin" - Colorado; Colorado Water Conservation Board, U. S. Department of Agriculture; 1962, 2) "The Collegiate Ran~~ Project - A Water Supply Development''; Sierra Madre Lode, Ltd.; Undated, 3) "Water Rights Evaluation in the Gunnison River Basin, Collegiate Range Project", The David E. Fleming Company; 1985. The latter report was commissioned by the City of Aurora. The Collegiate Range Project is proposed as a transmountain water diversion project. Essentially, water is to be diverted from the Taylor River and one of its tributaries, Texas Creek, and stored in Pieplant Reservoir. Water would be conveyed via the Taylor Platte aqueduct from Pieplant Reservoir to the South Platte River Basin.