Landscape Character Descriptions of the White River National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 5 of the 2020 Antelope, Deer and Elk Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Antelope, 2020 Deer and Elk Hunting Regulations Don't forget your conservation stamp Hunters and anglers must purchase a conservation stamp to hunt and fish in Wyoming. (See page 6) See page 18 for more information. wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS Access on Lands Enrolled in the Department’s Walk-in Areas Elk or Hunter Management Areas .................................................... 4 Hunt area map ............................................................................. 46 Access Yes Program .......................................................................... 4 Hunting seasons .......................................................................... 47 Age Restrictions ................................................................................. 4 Characteristics ............................................................................. 47 Antelope Special archery seasons.............................................................. 57 Hunt area map ..............................................................................12 Disabled hunter season extension.............................................. 57 Hunting seasons ...........................................................................13 Elk Special Management Permit ................................................. 57 Characteristics ..............................................................................13 Youth elk hunters........................................................................ -

Historical Information H.4 Pre-Event Reports Book 1 Project Rulison: Pre

Historical Information H.4 Pre-Event Reports Book 1 Project Rulison: Pre-Shot Predictions of Structural Effects HPR .2 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. PROJECT RULISON: Pre - Shot Predictions of Structural Effects John A. -~lume& Associates Research Division San ~rancisco,California March 1969 Prepared under Contract AT(26-1)-99 for the Nevada Operations Office, USAEC This page intentionally left blank PROJECT RULISON: PRE-SHOT PREDICTIONS OF STRUCTURAL EFFECTS CONTENTS -Page ABSTRACT ......................../'. .... i i I SUMMARY ............................ v INTRODUCTION.......................... 1 SEISMICITY ........................... 2 STRUCTURAL HAZARD EVALUATION .................. 3 EARTH STRUCTURAL HAZARDS .................... 11 HYDRAULIC STRUCTURE AND WATER SUPPLY HAZARDS .......... 17 SAFETY PRECAUTIONS AND EVACUATION RECOMt4ENDATIONS ....... 22 DAMAGE COST PREDICTIONS .................... 24 CONDITION SURVEYS ....................... 26 MAP (In pocket inside back cover) This page intentionally left blank . ~ ABSTRACT This report includes results of pre-RULISON structural response investigations and a preliminary evaluation of hazards associated with ground motion effects on buildings, reservoirs, and earth structures. Total damage repair costs from an engineering judg- ment prediction are provided. Spectral Matrix Method calcula- tions are now in progress. Also included are general safety recommendations. A summary of predictions follows: Structural Response Damaging motions are probable in the region inside 25 kilometers. Structural hazards exist in Grand Valley, at the Anvil Points Research Station, and at various small ranches out to a distance of 14 ki lometers from Ground Zero (GZ) . The area is much more densely populated than would appear from initial project informa- tion. Earth Structure Hazards Rockfall and hazards to slope stability create major problems. -

Moose Management Plan DAU

MOOSE MANAGEMENT PLAN DATA ANALYSIS UNIT M-5 Grand Mesa and Crystal River Valley Photo courtesy of Phil & Carol Nesius Prepared by Stephanie Duckett Colorado Division of Wildlife 711 Independent Ave. Grand Junction, CO 81505 M-5 DATA ANALYSIS UNIT PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GMUs: 41, 42, 43, 411, 421, 52, and 521 (Grand Mesa and Crystal River Valley) Land Ownership: 35% private; 65% public Post-hunt population: Previous objective: NA 2008 estimate: 125 Recommended: pending Composition Objective: Previous objective: NA 2008 estimate: 60 bulls: 100 cows Recommended: pending Background: The M-5 moose herd was established with translocated Shiras moose from Utah and Colorado in 2005 – 2007. The herd has exhibited strong reproduction and has pioneered into suitable habitat in the DAU. At this time, it is anticipated that there are approximately 125 moose in the DAU. The herd already provides significant watchable wildlife opportunities throughout the Grand Mesa and Crystal River Valley areas and it is anticipated that it will provide hunting opportunities in the near future. Significant Issues: Several significant issues were identified during the DAU planning process in M-5. The majority of people who provided input indicated strong interest in both hunting and watchable wildlife opportunities. There was less, but still significant, concern about both competition with livestock for forage and the possibility of habitat degradation, primarily in willow and riparian zones. The majority of stakeholders favored increasing the population significantly while staying below carrying capacity. There was strong support for providing a balance of opportunity and trophy antlered hunting in this DAU, and most respondents indicated a desire for quality animals. -

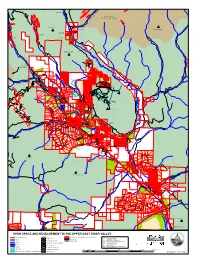

OPEN SPACE and DEVELOPMENT in the UPPER EAST RIVER VALLEY Open Space Subdivided Land & Single Family Residences Parcel Boundaries C.C

K E TO SCHOFIELD E R C R E MAROON BELLS P P SNOWMASS WILDERNESS O C GOTHIC MOUNTAIN GOTHIC TOWNSITE TEOCALLI MOUNTAIN (RMBL) Gothic Mountain Subdivision Washington Gulch (CBLT) Glee Biery C.E. Maxfield Meadows C.E. The Bench (CBLT) (CBLT) C.E. (CBLT) Rhea Easement C O U N T SNODGRASS MOUNTAIN Y 3 1 7 W E A A S S S L H T A IN T G R E T IV O E R N R I V G E U L R C The Reserve (C.E.) H R (COL) D RAGGEDS WILDERNESS Smith Hill #1 (CBLT) Divine C.E. (CBLT) Meridian Lake Park D R C I M H E T R MERIDIAN LAKE PARK O I G Gunsight D RESERVOIR I Bridge A Prospect C.A. N K Parcel CREE FUL (CBLT) L -JOY A H-BE K O E TOWN OF \( L MT. CRESTED BUTTE BLM O W N A NICHOLSON LAKE G S H L I A N K BLM G Smith Hill RanEches T ) O N Alpine Meadows C.A. G Glacier Lily U Donation L (CBLT) C Nevada C.E. H Lower Loop (CBLT) Parcels R Rolling River C.E. (CBLT) (CBLT) D Wildbird C.O. Investments Glacier Lily Estates Estates (CBLT) BLM Rice Parcel (CBLT) Peanut Mine C.E. (TCB) MT EMMONS Utley Parcel S LA (CBLT) TE Peanut Lake R Saddle Ridge C.A. Parcel (CBLT) IV ER PEANUT LAKE Gallin Parcel (CBLT) R CRESTED BUTTE D Robinson Parcel Three (CBLT) Trappers Crossing S Valleys L Kapushion Family P Confluence at C.B. -

Crystal River and Wast Sopris Creek Report Section 7

7. References Bredehoeft, J.D. 2006. On Modeling Philosophies. Ground Water, Vol. 44 (4), pp. 496-499. Bryant, B. and P.L. Martin. 1988. The Geologic Story of the Aspen Region -Mines, Glaciers and Rocks. Bulletin 1603. U.S. Geological Survey. CDNR. 2008. Guide to Colorado Water Rights, Well Permits, and Administration. Colorado Dept. of Natural Resources, Office of State Engineer. (http://www.water.state.co.us/pubs/wellpermitguide.pdf ). Daly, C. and G.L. Johnson. 1999. PRISM Spatial Climate Layers; PRISM Guide Book. PRISM Group, Oregon State University. Devlin, J.F., and M. Sophocleous. 2005. The Persistence of the Water Budget Myth and its Relationship to Sustainability. Hydrogeology Journal, Vol. 13(4), pp. 549-554. ESRI. 2002. Getting Started with ArcGISTM . ESRI, Redlands, California. Freethey, G.W., and G.E. Gordy. 1991. Geohydrology of Mesozoic Rocks in the Upper Colorado River Basin in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming, Excluding the San Juan Basin. Professional Paper 1411-C. U.S. Geological Survey. Geldon, A.L. 2003a. Geology of Paleozoic Rocks in the Upper Colorado River Basin in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming, Excluding the San Juan Basin. Professional Paper 1411-A. U.S. Geological Survey. Geldon, A.L. 2003b. Hydrologic Properties and Ground-Water Flow Systems of the Paleozoic Rocks in the Upper Colorado River Basin in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming, Excluding the San Juan Basin. Professional Paper 1411-B. U.S. Geological Survey. Harlan, R., K.E. Kolm, and E.D. Gutentag. 1989. Water Well Design and Construction. Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. -

C E N Oz Oi C C Oll a Ps E of T H E E Ast Er N Ui Nt a M O U Nt Ai Ns a N D Dr Ai

Research Paper T H E M E D I S S U E: C Revolution 2: Origin and Evolution of the Colorado River Syste m II GEOSPHERE Cenozoic collapse of the eastern Uinta Mountains and drainage evolution of the Uinta Mountains region G E O S P H E R E; v. 1 4, n o. 1 Andres Aslan 1 , Marisa Boraas-Connors 2 , D o u gl a s A. S pri n k el 3 , Tho mas P. Becker 4 , Ranie Lynds 5 , K arl E. K arl str o m 6 , a n d M att H eizl er 7 1 Depart ment of Physical and Environ mental Sciences, Colorado Mesa University, 1100 North Avenue, Grand Junction, Colorado 81501, U S A doi:10.1130/ G E S01523.1 2 Depart ment of Geosciences, Colorado State University, Natural Resources Building, Roo m 322, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, U S A 3 Utah Geological Survey, 1594 W North Te mple, Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-6100, U S A 1 5 fi g ur e s; 1 t a bl e; 4 s u p pl e m e nt al fil e s 4 Exxon Mobil Exploration Co mpany, 22777 Spring woods Village Park way, Spring, Texas 77389, U S A 5 Wyo ming State Geological Survey, P. O. Box 1347, Lara mie, Wyo ming 82073, U S A 6 Depart ment of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Ne w Mexico, Redondo Drive NE, Albuquerque, Ne w Mexico 87131, U S A C O R RESP O N DE N CE: aaslan @colorado mesa .edu 7 Ne w Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, Ne w Mexico Tech, 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, Ne w Mexico 87801, U S A CI T A TI O N: Aslan, A., Boraas- Connors, M., Sprinkel, D. -

BACKCOUNTRY CACHE a Newsletter for Members of CMC Backpacking Section

BACKCOUNTRY CACHE A Newsletter for Members of CMC Backpacking Section May 2021 CHAIR'S CORNER - Uwe Sartori Members often ask what do trip leaders do in getting a trip built and across the finish line? Tied into the answer is the awesome value CMC members receive each time they sign up and do a CMC trip. (Think about it. If you go to a guide service, you are likely paying hundreds of dollars a day.) The chart below shows my investment for an upcoming backpacking trip. This personal investment is repeated by many of our trip leaders regardless of the recreational activity. For this 2 day backpacking trip, there are 24 hours of prep/debrief/admin work and 20 hours of trip activity time; 44 hours total. You can begin to understand why the BPX Section is super keen on having our members keep their commitment and help us AVOID ROSTER CHURN. Having trips cancel due to CMC members dropping out is the bane of trip leaders. Show respect and community by keeping your commitment when signing up for a CMC adventure. I guarantee you will not regret it. BPX TRIPS FOR NEXT 2 MONTHS E=Easy M=Moderate D=Difficult June - July Trips With Openings* Jun 1-3 Tue-Thu M Camping, Hiking, Fishing at Browns Canyon Nat'l Monument Jun 9-11 Wed-Fri E Mayflower and Mohawk Lakes, White River NF Jun 11-13 Fri-Sun M Just-in-Time Wigwam Park, Lost Creek Wilderness Jun 25-28 Fri-Mon D Colorado Trail - Collegiate West Exploratory Jun 29- Tue-Thu D Willow and Salmon Lakes, Eagles Nest Wilderness Jul 1 Jul 1-2 Thu-Fri D Macey Lakes and Colony Baldy, Sangre de Cristo Wilderness -

Comprehensive Lower Fryingpan River Assessment 2013-2015

ROARING FORK CONSERVANCY Comprehensive Lower Fryingpan River Assessment 2013-2015 Summary Given current concerns over the health of the Fryingpan River and fishery, Roaring Fork Conservancy is pursuing a comprehensive study to better understand the current state of the Fryingpan, and create a long-term monitoring plan to track trends over time. Roaring Fork Conservancy’s initial aquatic studies will examine macroinvertebrates, flows, and water temperatures. In addition, we will conduct an assessment of the American dipper population, the extent of Didymosphenia Geminata, and update the 2002 Fryingpan Valley Economic Study to evaluate the role of the river in community vitality. Roaring Fork Conservancy will also work with Ruedi Water and Power Authority, Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Water Conservation District, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to investigate how new and existing contracts for Ruedi Reservoir water can be managed to ensure river and associated economic health. Upon completion of these studies, Roaring Fork Conservancy will disseminate the findings to federal, state and local government agencies and residents of the Fryingpan River Valley. Goal To ensure the environmental and economic sustainability of the Lower Fryingpan River, including its designation as a “Gold Medal Fishery”. Objectives Assess the current biological health of the Lower Fryingpan River and if impaired identify potential causal factors and solutions. Recommend a long-term monitoring strategy for the Fryingpan River. Update Roaring Fork Conservancy’s 2002 Fryingpan Valley Economic Study. Determine and pursue voluntary and, if necessary, policy/legislative solutions for managing releases from Ruedi Reservoir to prevent negative economic and environmental impacts. Components & Time Frame ROARING FORK CONSERVANCY Comprehensive Lower Fryingpan River Assessment 2013-2014 1 BACKGROUND The headwaters of the Fryingpan sub-watershed drain westward from the Continental Divide into the Fryingpan River, which meets the Roaring Fork River at Basalt. -

Mesa Cortina / South Willow Falls

U. S. Department of Agriculture Dillon Ranger District 680 Blue River Parkway Silverthorne, CO 80498 (970) 468-5400 MESA CORTINA / SOUTH WILLOW FALLS - FDT 32 / 60 Difficulty: EASY TO MODERATE Trail Use: Moderate Length: 2.7 miles one-way to the Gore Range Trail (FDT 60) 4.2 miles one-way to the South Willow Falls Elevation: Start at 9,217 feet and ends at 10,007 feet (highest point 10,007 feet) Elevation Gain: +1,043 feet - 253 feet = +790 feet Open To: HIKING, HORSE, X-C SKIING, SNOWSHOEING Access: From I-70 take Exit 205, Silverthorne / Dillon, and travel north on HWY 9 to the first traffic light at the intersection of Rainbow Drive / Wildernest Road. Turn left onto Wildernest Road / Ryan Gulch Rd. Continue through two stoplights onto Buffalo Mountain Drive. After 0.8 miles, turn right onto Lakeview Drive. Travel 0.45 miles and turn left onto Aspen Drive. The Mesa Cortina trailhead and parking area will be on your right in 0.15 miles. Trail Highlights: This trail enters the Eagles Nest Wilderness Area. There are great views of Dillon Reservoir and the entire Blue River Valley from the trailhead. The trail winds through aspen groves into a meadow which offers a good view of the Ptarmigan Peak Wilderness. After the meadow is the Eagles Nest Wilderness boundary. The trail then travels through lodgepole pine forests and crosses South Willow Creek just before intersecting the Gore Range Trail (FDT 60). Continue left (west) on the Gore Range Trail toward South Willow Falls. Eventually you will come to a junction which is the dead-end spur trail to the falls. -

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

Coal Fields of Northwestern Colorado and Northeastern Utah

COAL FIELDS OF NORTHWESTERN COLORADO AND NORTHEASTERN UTAH. By HOYT S. GALE. INTRODUCTION. NATURE OF THE PRESENT INVESTIGATION. This paper is a preliminary statement of the results of work in the coal fields of northwestern Colorado and northeastern Utah during the summer of 1907.° In 1905 a preliminary reconnaissance of the Yampa coal field, of Routt County, was made.6 In the summer of 1906 similar work was extended southwestward from the Yampa field, and the Danforth Hills and Grand Hogback coal fields, of Routt, Rio Blanco, and Garfield counties, were mapped.6 The work of the past season was a continuation of that of the two preceding years, extend ing the area studied westward through Routt and Rio Blanco counties, Colo., and including some less extensive coal fields in^Uinta County, Utah, and southern Uinta County, Wyo. ACCESSIBILITY. At present these fields have no_ railroad connection, although surveys for several projected lines have recently been made into the region. Of these lines, the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway ("Moffat road") is under active construction in .the eastern part of Routt County and bids fair to push westward not far from the lower Yampa and White River fields in the near future. An extension of the Uintah Railway has been surveyed from Dragon to Vernal, Utah, crossing the projected route of the "MofFat road" near Green River. The Union Pacific Railroad has made a preliminary survey south from Rawlins, Wyo., intending to reach the Yampa Valley in the vicinity of Craig. a A more complete report combining the results of the preceding season's work in the Danforth Hills and Grand Hogback fields with those of last season's work as outlined here, together with detailed contour maps of the whole area, will be published as a (separate bulletin of the Survey. -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21