PDAAJ669.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office Attendants and Cleaners Certified

OFFICE ATTENDANTS AND CLEANERS CERTIFIED For the first time in the history of “You can use the certificates the judiciary, office attendants and to get jobs elsewhere includ- cleaners have been certified after ing overseas because IWED they received training to improve is an accredited training or- their performance on the job in a ganization (ATO) by bid to make Jamaica’s judiciary NCTVET- Heart Trust/NTA the best in the Caribbean in three and HEART is a recognized years and among the best in the institution,” the Chief Justice world in six years. emphasized. The four-day training, which was One of the participants in the conducted by the Institute of training exercise Rosemarie The Hon. Mr. Justice Bryan Sykes OJ CD, Workforce Education and Devel- Chanteloupe from the Chief Justice, hands over certificate to Jennifer opment (IWED) at the Knutsford Manchester Parish Court said Bryan from the Traffic Court at the Award Court Hotel in Kingston “I learn a lot and I appreciate Ceremony for Office Attendants held at the everything that they did for (November 18-19, 2019) and Riu Terra Nova All-Suite Hotel in St. Andrew on Hotel in Montego Bay, St. James December 19, 2019. us. The training helped us to (November 21-22, 2019), covered learn more about our work ethic and to have better a range of topics such as: custom- and urged them to apply what they have customer relation skills.” er relations, proper sanitation, garnered from the training exercise to food handling practices and pro- their jobs. Another participant, Shaun cedures, occupational safety and Huggarth from the Hanover Chief Justice Sykes said the training is workplace professionalism. -

Parish Courts of Jamaica the Chief Justice's Second Quarter Statistics

Parish Courts of Jamaica The Chief Justice’s Second Quarter Statistics Report for 2020 – Civil Matters 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Methodology ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………….......6 Corporate Area Court – Civil Division .............................................................................................................. ...8 Hanover Parish Court ....................................................................................................................................... .20 St. James Parish Court ...................................................................................................................................... .28 Trelawny Parish Court ...................................................................................................................................... .36 St. Ann Parish Court ......................................................................................................................................... .42 St. Catherine Parish Court………………………………………………………………………………………….50 Portland Parish Court ....................................................................................................................................... .60 St. Mary Parish Court………………………………………………………………………………………….........65 -

Jamaica's Parishes and Civil Registration Districts

Jamaican registration districts Jamaica’s parishes and civil registration districts [updated 2010 Aug 15] (adapted from a Wikimedia Commons image) Parishes were established as administrative districts at the English conquest of 1655. Though the boundaries have changed over the succeeding centuries, parishes remain Jamaica’s fundamental civil administrative unit. The three counties of Cornwall (green, on the map above), Middlesex (pink), and Surrey (yellow) have no administrative relevance. The present parishes were consolidated in 1866 with the re-division of eight now- extinct entities, none of which will have civil records. A good historical look at the parishes as they changed over time may be found on the privately compiled “Jamaican Parish Reference,” http://prestwidge.com/river/jamaicanparishes.html (cited 2010 Jul 1). Civil registration of vital records was mandated in 1878. For civil recording, parishes were subdivided into named registration districts. Districts record births, marriages (but not divorces), and deaths since the mandate. Actual recording might not have begun in a district until several years later after 1878. An important comment on Jamaican civil records may be found in the administrative history available on the Registrar General’s Department Website at http://apps.rgd.gov.jm/history/ (cited 2010 Jul 1). This list is split into halves: 1) a list of parishes with their districts organized alphabetically by code; and 2) an alphabetical index of district names as of the date below the title. As the Jamaican population grows and districts are added, the list of registration districts lengthens. The parish code lists are current to about 1995. Registration districts created after that date are followed by the parish name rather than their district code. -

Environmental Impact Statement and Solidwaste Management Plan

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT AND SOLIDWASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN OF THE PROPOSED SOLIDWASTE DUMP AT WINCHESTER ESTATES IN HANOVER, JAMAICA Submitted to RIU HOTEL INTERNATIONAL Hanover, Jamaica JULY 2002 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT AND SOLIDWASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN OF THE PROPOSED SOLIDWASTE DUMP AT WINCHESTER ESTATES IN HANOVER, JAMAICA Submitted to RIU HOTEL INTERNATIONAL Hanover, Jamaica Prepared by C.L. ENVIRONMENTAL Apartment 7 117 Constant Spring Road Kingston 10 JULY 2002 RIU II EIS/SWMP ii C.L. Environmental Co. Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ...............................................................................................III 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY TEAM ...................................................................................................... 1 3.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE EXISTING ENVIRONMENT................................ 2 3.1 LOCATION........................................................................................................ 2 3.2 CLIMATE........................................................................................................... 3 3.3 TOPOGRAPHY AND DRAINAGE................................................................... 3 3.4 SOILS.................................................................................................................. 4 3.5 -

Jamaica North Coast Development Project External Evaluator: Hajime Onishi (Padeco Co., Ltd.) Field Survey: December 2005 1. Project Profile and Japan’S ODA Loan

Jamaica North Coast Development Project External Evaluator: Hajime Onishi (Padeco Co., Ltd.) Field Survey: December 2005 1. Project Profile and Japan’s ODA Loan (Clockwise from upper left) A waste Map of project area stabilization pond, the Northern Highway, a waste water settling tank, and Ocho Rios Port 1.1 Background Back in the year 1987 Jamaica’s tourism industry was the country’s most important industry, bringing in roughly 40% of its foreign currency revenue. All of Jamaica’s major tourist spots, such as Montego Bay, Ocho Rios, and Negril are located in the country’s northern region. Lodging establishments like hotels have been steadily installed, yet conversely the level of development for infrastructure like roads and water supply and sewerage is extremely low within this region. This has been seen as the greatest factor threatening the ongoing growth of the tourism industry. Starting from such a situation, in 1990 a Special Assistance for Project Formation (SAPROF) study was conducted and five sub-projects were selected to promote tourism and protect tourist attractions within the northern region1 . In addition, this project was implemented as a joint financing project with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)2 . 1.2 Objective This project will develop and improve infrastructure such as water supply and 1 The five sub-projects are: (1) the Montego Bay Sewerage, (2) the Lucea/Negril Water Supply System, (3) the Northern Highway Improvement, (4) the Montego Bay Drainage and Flood Control, and (5) the Ocho Rios Port Expansion. 2 A portion of the operating costs for the Project Management Unit (PMU) and the implementation expenses for the Montego Bay Environmental Monitoring Program (carried out for five years from 1992-1996), among others, were funded through financing from USAID. -

Negril & West Coast

© Lonely Planet Publications 216 Negril & West Coast NEGRIL & WEST COAST NEGRIL & WEST COAST In the 1970s, Negril lured hippies with its offbeat beach-life to a countercultural Shangri-la where anything goes. To some extent anything still goes here, but the innocence left long ago. To be sure, the gorgeous 11km-long swath of sand that is Long Beach is still kissed by the serene waters into which the sun melts every evening in a riot of color that will transfix even the most jaded. And the easily accessible coral reefs offer some of the best diving in the Caribbean. At night, rustic beachside music clubs keep the reggae beat going without the watered-down- for-tourist schmaltz that so often mars the hotspots of Montego Bay and Ocho Rios. Yet these undeniable attractions have done just that – attract. In the last three decades, Negril has exploded as a tourist venue, and today the beach can barely be seen from Nor- man Manley Blvd for the intervening phalanx of beachside resorts. And with tourism comes the local hustle – you’re very likely to watch the sunset in the cloying company of a ganja dealer or an aspiring tour-guide-cum-escort. The less-developed West End lies on the cliffs slightly to the south of Long Beach. Here smaller, more characterful hotels mingle with intimate jerk shacks and lively bars, and it’s much easier to mix with locals without the perpetual sense of just being seen as an exten- sion of your wallet. The sunset’s just as magnificent from the cliffs, and you’ll probably get a better idea of what Negril was like 40 years ago. -

Civil Matters)

Parish Courts of Jamaica The Chief Justice’s Annual Statistics Report for 2020 (Civil Matters) JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2020 2019 Gross Case Disposal rate (%) 50.84 77.29 Gross Case Clearance Rate (%) 95.34 90.73 Trial Date Certainty Rate (%) 81.16 79.40 Average time to disposition 10.40 5.67 months months 1 Prepared by: The Court Statistics Unit, Supreme Court of Jamaica Kings Street, Kingston. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chief Justice’s Message ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………….......8 Corporate Area Court – Civil Division .............................................................................................................. .10 Hanover Parish Court ....................................................................................................................................... .27 Manchester Parish Court (Small Claims Court) .............................................................................................. .38 St. Catherine Parish Court ............................................................................................................................... -

Draft Report

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT For the Proposed Dolphin Park, Paradise, Hanover Draft Report Prepared for Dolphin Cove Ltd. Environmental Management April 17th 2007 Consultants (Caribbean) Ltd 61 Mansfield Meadows, Ocho Rios St. Ann, Jamaica 876-974-7423 [email protected] ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED DOLPHIN PARK AT PARADISE, HANOVER. April 17th 2007. Prepared by Environmental Management Consultants (Caribbean) Ltd. on behalf of Dolphin Cove Ltd. in support of their application for an Environmental Permit under the Natural Resources Conservation Act of Jamaica (1990). No part of this report may be reproduced without the written permission of Dolphin Cove Ltd. Should the document be cited, the formal citation should read: Environmental Management Consultants (Caribbean) Ltd. 2007. Environmental Impact Assessment for the Proposed Dolphin Park at Paradise, Hanover. 1 Table of Contents 1 Preamble ..............................................................................................................................................................1 2 Project Description .............................................................................................................................................3 2.1 Section Overview..........................................................................................................................................3 2.2 Project Overview ..........................................................................................................................................3 -

Parish Courts of Jamaica the Chief Justice's First Quarter Statistics

THE CHIEF JUSTICE’S FIRST QUARTER STATISTICS REPORT ON CRIMINAL MATTERS IN THE PARISH COURTS – 2020 Parish Courts of Jamaica The Chief Justice’s First Quarter Statistics Report for 2020 JANUARY TO MARCH 2019 2020 Case Disposal Rates (%) 53.74 48.59 Case Clearance Rates (%) 103.46 96.47 Trial Date Certainty Rates (%) 82 84 Courtroom utilization Rate (%) 59.85 57.78 Prepared by: The Court Statistics Unit with the support of the IT Unit, Supreme Court of Jamaica Kings Street, Kingston. 1 THE CHIEF JUSTICE’S FIRST QUARTER STATISTICS REPORT ON CRIMINAL MATTERS IN THE PARISH COURTS – 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chief Justice’s Message……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…...3 Executve Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..5 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................... 11 Chapter 1.0: Criminal Case Actvity Statistics .............................................................................................. 13 Chapter 2.0: Criminal Case Demographics.................................................................................................. 47 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 87 Chapter 4.0: Glossary of Terms ................................................................................................................... 89 2 THE CHIEF JUSTICE’S FIRST QUARTER STATISTICS REPORT -

Analyzing the Impact of Participatory-Plannded Conservation Policies in the Negril Environmental Protection Area, Western, Jamaica

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ANALYZING THE IMPACT OF PARTICIPATORY PLANNED CONSERVATION POLICIES IN THE NEGRIL ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AREA, WESTERN JAMAICA Lovette Miller Anderson, Doctor of Philosophy, 2007 Dissertation directed by: Professor Ruth Defries Department of Geography This dissertation research sought to determine the ways in which the participatory- planned conservation policies influence changes in local populations’ natural resource use. The research took place in the Negril Environmental Protection Area, western Jamaica and covered the period 1990 to 2005. The two major questions asked were 1) In what ways do participatory-planned conservation policies influence changes in the protected area’s natural resource use? 2) How does group membership and demography influence the perception of the conservation policies and of changes in natural resource use? The research employed trend analyses, content analyses, a population survey, discriminant analyses and semi-structured interviews to answer the research questions. In general, the research finds that national socioeconomic development interests were given priority over the participatory-planned conservation policies. The changes in local populations’ natural resource use were primarily due to the national socioeconomic policies that were in place prior to the protected area designation as well as those that were implemented during the study period. Second, the research finds that, in general, groups that have shared histories were homogeneous in their views of conservation and/or development. In contrast, newer entrants to the protected area were generally heterogeneous in their views of conservation and/or development. Further, the research finds that changes in the demographic characteristics of local populations significantly influence the perception of conservation and development. -

First Quarter Statistical Report on Criminal Matters in the Parish Courts

Statistical Report for the Parish Courts of Jamaica 2017 PARISH COURTS OF JAMAICA March, 2017 STATISTICAL REPORT ON CRIMINAL CASES 2017 Prepared by the Statistics Unit with the support of the Information Technology Unit Supreme Court Jamaica 1 Statistical Report for the Parish Courts of Jamaica 2017 Table of Contents Introduction...................................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary........................................................................................................................5 Case activity statistics…………..........................................................................................................8 Case demographics…………….........................................................................................................19 Conclusion....................................................................................................................................36 2 Statistical Report for the Parish Courts of Jamaica 2017 Introduction On July 01st, 2016, an upgraded data capture sheet for criminal matters was launched in the parish courts. The aim of this data capture platform is to create a robust and comprehensive mechanism for capturing data on the progression of criminal matters in the parish courts. This data will afford the Court system the opportunity to monitor the efficiency with which criminal matters move through the Justice system and to align resources accordingly. The country’s policy making -

Appendix I. Clergymen Who Arrived in V Irginia Between 1607 and 1699

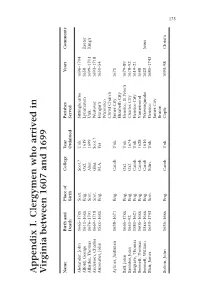

Appendix I. Clergymen who arrived in Virginia between 1607 and 1699 Name Birth and Place of College Year Parishes Years Comments Death Birth Ordained Served Alexander, John 1665–17xx Scot. Scot.? Unk. Sittingbourne 1696–1704 Alford, George 1611–16xx Eng. Oxf. 1619 Lynnhaven 1658 Exeter Allardes, Thomas 1676–1701 Scot. Aber. 1699 Unk. 1699–1701 King’s Anderson, Charles 1669–1718 Scot. Glas. Scot.? Westover 1693–1718 Armourier, John 15xx–16xx Eng. M.A. Yes Hungar’s 1651–54 Wicomico Christ Church Aylmer, Justinian 1638–1671 Eng. Camb. Unk. James City 1671 Elizabeth City Ball, John 1665–17xx Eng. Oxf. Unk. Henrico, St Peter’s 1679–89 Banister, John 1650–92 Eng. Oxf. 1674 Charles City 1678–92 Bargrave, Thomas 1581–1621 Eng. Camb. Unk. Henrico City 1619–21 Bennett, Thomas 1605–16xx Eng. Camb. 1628 Nansemond 1648 Bennett, William 15xx–16xx Eng. Camb 1616 Warwisqueake 1623 Jesus Blair, James 1653–1743 Scot. Edin. Unk. Henrico 1685–1743 James City Bruton Bolton, John 1635–16xx Eng. Camb. Unk. Cople 1693–98 Christ’s 175 176 (Continued) Name Birth and Place of College Year Parishes Years Comments Death Birth Ordained Served Bolton, Francis 1595–16xx Eng. Camb. Unk. Elizabeth City 1621–30 Accomac? 1623–26 Warwisqueake Bowker, James 1665–1703 Eng. Camb. Unk. Kempton 1690–1703 St Peter’s Bracewell, Robert 1611–68 Eng. Oxf. Unk. Isle of Wight 1653–68d. Bucke, Richard 1584–1623 Eng. Camb. Unk. James City 1610–23 Bushnell, James 16xx–17xx Unk. Unk. Unk. Martin’s Hundred 1696–1702 Butler, William 1647–17xx Eng. Camb. Unk.