The Colons and Semicolon the Colon the Colon (:) Seems to Bewilder Many People, Though It’S Really Rather Easy to Correctly, Since Has Only One Major Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Gut Microbiota and Colon Diseases with a Focus on Adenomatous Colon Polyps

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review An Overview of Gut Microbiota and Colon Diseases with a Focus on Adenomatous Colon Polyps Oana Lelia Pop 1 , Dan Cristian Vodnar 1 , Zorita Diaconeasa 1 , Magdalena Istrati 2, 3 4 1, Adriana Bint, int, an , Vasile Virgil Bint, int, an , Ramona Suharoschi * and Rosita Gabbianelli 5,* 1 Department of Food Science, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, 400372 Cluj-Napoca, Romania; [email protected] (O.L.P.); [email protected] (D.C.V.); [email protected] (Z.D.) 2 Regional Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology “Prof. Dr. Octavian Fodor”, 400158 Cluj-Napoca, Romania; [email protected] 3 1st Medical Clinic, Department of Gastroenterology, Emergency County Hospital, 400006 Cluj Napoca, Romania; [email protected] 4 1st Surgical Clinic, Department of Surgery, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj Napoca, 400006 Cluj Napoca, Romania; [email protected] 5 Unit of Molecular Biology, School of Pharmacy, University of Camerino, Via Gentile III da Varano, 62032 Camerino, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.S.); [email protected] (R.G.) Received: 6 August 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 5 October 2020 Abstract: It is known and accepted that the gut microbiota composition of an organism has an impact on its health. Many studies deal with this topic, the majority discussing gastrointestinal health. Adenomatous colon polyps have a high prevalence as colon cancer precursors, but in many cases, they are hard to diagnose in their early stages. Gut microbiota composition correlated with the presence of adenomatous colon polyps may be a noninvasive and efficient tool for diagnosis with a high impact on human wellbeing and favorable health care costs. -

Punctuation Guide

Punctuation guide 1. The uses of punctuation Punctuation is an art, not a science, and a sentence can often be punctuated correctly in more than one way. It may also vary according to style: formal academic prose, for instance, might make more use of colons, semicolons, and brackets and less of full stops, commas, and dashes than conversational or journalistic prose. But there are some conventions you will need to follow if you are to write clear and elegant English. In earlier periods of English, punctuation was often used rhetorically—that is, to represent the rhythms of the speaking voice. The main function of modern English punctuation, however, is logical: it is used to make clear the grammatical structure of the sentence, linking or separating groups of ideas and distinguishing what is important in the sentence from what is subordinate. It can also be used to break up a long sentence into more manageable units, but this may only be done where a logical break occurs; Jane Austen's sentence ‗No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy, would ever have supposed her born to be a heroine‘ would now lose its comma, since there is no logical break between subject and verb (compare: ‗No one would have supposed …‘). 2. The main stops and their functions The full stop, exclamation mark, and question mark are used to mark off separate sentences. Within the sentence, the colon (:) and semicolon (;) are stronger marks of division than the comma, brackets, and the dash. Properly used, the stops can be a very effective method of marking off the divisions and subdivisions of your argument; misused, they can make it barely intelligible, as in this example: ‗Donne starts the poem by poking fun at the Petrarchan convention; the belief that one's mistress's scorn could make one physically ill, he carries this one step further…‘. -

Punctuation: Program 8-- the Semicolon, Colon, and Dash

C a p t i o n e d M e d i a P r o g r a m #9994 PUNCTUATION: PROGRAM 8-- THE SEMICOLON, COLON, AND DASH FILMS FOR THE HUMANITIES & SCIENCES, 2000 Grade Level: 8-13+ 22 mins. DESCRIPTION How does a writer use a semicolon, colon, or dash? A semicolon is a bridge that joins two independent clauses with the same basic idea or joins phrases in a series. To elaborate a sentence with further information, use a colon to imply “and here it is!” The dash has no specific rules for use; it generally introduces some dramatic element into the sentence or interrupts its smooth flow. Clear examples given. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: Language Arts–Writing • Standard: Uses grammatical and mechanical conventions in written compositions Benchmark: Uses conventions of punctuation in written compositions (e.g., uses commas with nonrestrictive clauses and contrasting expressions, uses quotation marks with ending punctuation, uses colons before extended quotations, uses hyphens for compound adjectives, uses semicolons between independent clauses, uses dashes to break continuity of thought) (See INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1-4.) INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1. To explain the proper use of a semicolon to combine independent clauses and in lists with commas. 2. To show the correct use of colons for combining information and in sentence fragments. 3. To illustrate the use of a dash in sentences. 4. To show some misuses of the semicolon, colon, and dash. BACKGROUND INFORMATION The semicolon, colon, and dash are among the punctuation marks most neglected by students and, sad to say, teachers. However, professional writers—and proficient writers in business—use them all to good effect. -

Review of Set-Theoretic Notations and Terminology A.J

Math 347 Review of Set-theoretic Notations and Terminology A.J. Hildebrand Review of Set-theoretic Notations and Terminology • Sets: A set is an unordered collection of objects, called the elements of the set. The standard notation for a set is the brace notation f::: g, with the elements of the set listed inside the pair of braces. • Set builder notation: Notation of the form f::: : ::: g, where the colon (:) has the meaning of \such that", the dots to the left of the colon indicate the generic form of the element in the set and the dots to 2 the right of the colon denote any constraints on the element. E.g., fx 2 R : x < 4g stands for \the set of 2 all x 2 R such that x < 4"; this is the same as the interval (−2; 2). Other examples of this notation are f2k : k 2 Zg (set of all even integers), fx : x 2 A and x 2 Bg (intersection of A and B, A \ B). 2 Note: Instead of a colon (:), one can also use a vertical bar (j) as a separator; e.g., fx 2 R j x < 4g. Both notations are equally acceptable. • Equality of sets: Two sets are equal if they contain the same elements. E.g., the sets f3; 4; 7g, f4; 3; 7g, f3; 3; 4; 7g are all equal since they contain the same three elements, namely 3, 4, 7. • Some special sets: • Empty set: ; (or fg) • \Double bar" sets: 1 ∗ Natural numbers: N = f1; 2;::: g (note that 0 is not an element of N) ∗ Integers: Z = f:::; −2; −1; 0; 1; 2;::: g ∗ Rational numbers: Q = fp=q : p; q 2 Z; q 6= 0g ∗ Real numbers: R • Intervals: ∗ Open interval: (a; b) = fx 2 R : a < x < bg ∗ Closed interval: [a; b] = fx 2 R : a ≤ x ≤ bg ∗ Half-open interval: [a; b) = fx 2 R : a ≤ x < bg • Universe: U (\universe", a \superset" of which all sets under consideration are assumed to be a subset). -

International Language Environments Guide

International Language Environments Guide Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. Part No: 806–6642–10 May, 2002 Copyright 2002 Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle, Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. All rights reserved. This product or document is protected by copyright and distributed under licenses restricting its use, copying, distribution, and decompilation. No part of this product or document may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written authorization of Sun and its licensors, if any. Third-party software, including font technology, is copyrighted and licensed from Sun suppliers. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, docs.sun.com, AnswerBook, AnswerBook2, Java, XView, ToolTalk, Solstice AdminTools, SunVideo and Solaris are trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Products bearing SPARC trademarks are based upon an architecture developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. SunOS, Solaris, X11, SPARC, UNIX, PostScript, OpenWindows, AnswerBook, SunExpress, SPARCprinter, JumpStart, Xlib The OPEN LOOK and Sun™ Graphical User Interface was developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. for its users and licensees. Sun acknowledges the pioneering efforts of Xerox in researching and developing the concept of visual or graphical user interfaces for the computer industry. -

List of Approved Special Characters

List of Approved Special Characters The following list represents the Graduate Division's approved character list for display of dissertation titles in the Hooding Booklet. Please note these characters will not display when your dissertation is published on ProQuest's site. To insert a special character, simply hold the ALT key on your keyboard and enter in the corresponding code. This is only for entering in a special character for your title or your name. The abstract section has different requirements. See abstract for more details. Special Character Alt+ Description 0032 Space ! 0033 Exclamation mark '" 0034 Double quotes (or speech marks) # 0035 Number $ 0036 Dollar % 0037 Procenttecken & 0038 Ampersand '' 0039 Single quote ( 0040 Open parenthesis (or open bracket) ) 0041 Close parenthesis (or close bracket) * 0042 Asterisk + 0043 Plus , 0044 Comma ‐ 0045 Hyphen . 0046 Period, dot or full stop / 0047 Slash or divide 0 0048 Zero 1 0049 One 2 0050 Two 3 0051 Three 4 0052 Four 5 0053 Five 6 0054 Six 7 0055 Seven 8 0056 Eight 9 0057 Nine : 0058 Colon ; 0059 Semicolon < 0060 Less than (or open angled bracket) = 0061 Equals > 0062 Greater than (or close angled bracket) ? 0063 Question mark @ 0064 At symbol A 0065 Uppercase A B 0066 Uppercase B C 0067 Uppercase C D 0068 Uppercase D E 0069 Uppercase E List of Approved Special Characters F 0070 Uppercase F G 0071 Uppercase G H 0072 Uppercase H I 0073 Uppercase I J 0074 Uppercase J K 0075 Uppercase K L 0076 Uppercase L M 0077 Uppercase M N 0078 Uppercase N O 0079 Uppercase O P 0080 Uppercase -

Top Ten Tips for Effective Punctuation in Legal Writing

TIPS FOR EFFECTIVE PUNCTUATION IN LEGAL WRITING* © 2005 The Writing Center at GULC. All Rights Reserved. Punctuation can be either your friend or your enemy. A typical reader will seldom notice good punctuation (though some readers do appreciate truly excellent punctuation). However, problematic punctuation will stand out to your reader and ultimately damage your credibility as a writer. The tips below are intended to help you reap the benefits of sophisticated punctuation while avoiding common pitfalls. But remember, if a sentence presents a particularly thorny punctuation problem, you may want to consider rephrasing for greater clarity. This handout addresses the following topics: THE COMMA (,)........................................................................................................................... 2 PUNCTUATING QUOTATIONS ................................................................................................. 4 THE ELLIPSIS (. .) ..................................................................................................................... 4 THE APOSTROPHE (’) ................................................................................................................ 7 THE HYPHEN (-).......................................................................................................................... 8 THE DASH (—) .......................................................................................................................... 10 THE SEMICOLON (;) ................................................................................................................ -

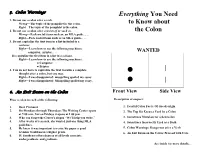

Colon Warnings Everything You Need 1

5. Colon Warnings Everything You Need 1. Do not use a colon after a verb. Wrong—The topic of the pamphlet is: the colon. to Know about Right—The topic of the pamphlet is the colon. 2. Do not use a colon after consists of or such as. the Colon Wrong—Pack useful items such as: an MLA guide, . Right—Pack useful items such as an MLA guide, . 3. Do not capitalize the first item in a list included in a sentence. Right—Learn how to use the following machines: computer, printer, . WANTED Do capitalize the first item in a list in a column. Right—Learn how to use the following machines: ● Computer ● Printer 4. You do not have to capitalize the first word in a complete │ thought after a colon, but you may. Right—I was disappointed: misspelling spoiled my essay. Right—I was disappointed: Misspelling spoiled my essay. │ : 6. An Exit Exam on the Colon Front View Side View Place a colon in each of the following: Description of suspect: 1. Dear Professor 1. Fearful Colon Facts: Of Greek origin 2. On Mondays through Thursdays The Writing Center opens 2. The Top Six Excuses Used by a Colon at 9 00 a.m., but on Fridays it opens at 1 00 p.m. 3. Who can forget the Center's slogan “We'll help you write.” 3. Sometimes Mistaken for a Semicolon 4. After weeks of research, she wanted just one thing MLA 4. Sometimes Incorrectly Used as a Dash guidelines. 5. He knew it was important to revise his paper a good 5. -

Set (Mathematics) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Set (mathematics) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A set in mathematics is a collection of well defined and distinct objects, considered as an object in its own right. Sets are one of the most fundamental concepts in mathematics. Developed at the end of the 19th century, set theory is now a ubiquitous part of mathematics, and can be used as a foundation from which nearly all of mathematics can be derived. In mathematics education, elementary topics such as Venn diagrams are taught at a young age, while more advanced concepts are taught as part of a university degree. Contents The intersection of two sets is made up of the objects contained in 1 Definition both sets, shown in a Venn 2 Describing sets diagram. 3 Membership 3.1 Subsets 3.2 Power sets 4 Cardinality 5 Special sets 6 Basic operations 6.1 Unions 6.2 Intersections 6.3 Complements 6.4 Cartesian product 7 Applications 8 Axiomatic set theory 9 Principle of inclusion and exclusion 10 See also 11 Notes 12 References 13 External links Definition A set is a well defined collection of objects. Georg Cantor, the founder of set theory, gave the following definition of a set at the beginning of his Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre:[1] A set is a gathering together into a whole of definite, distinct objects of our perception [Anschauung] and of our thought – which are called elements of the set. The elements or members of a set can be anything: numbers, people, letters of the alphabet, other sets, and so on. -

Commonly Misused Punctuation: Colons And

COMMONLY MISUSED PUNCTUATION: COLONS AND DASHES Center for Writing and Speaking Colons and dashes are two of the most mysterious and misunderstood marks of punctuation. This handout is meant to demystify and clarify the function of these forms of punctuation, so that you can use them more accurately. Colon Colons are used after an independent clause. What is an independent clause? It is a sentence that can stand alone as a complete thought. The colon is often used for listing things, before quotations that are three or more lines, and in place of a semicolon between two related independent clauses. Example A: You may need the following items to go camping: a sleeping bag, a tent, a blanket, clean undies, and marshmallows. Example B: This is best described by Maslow in his paper “A Theory of Human Motivation”: What a man can be, he must be. This need we may call self-actualization…It refers to the desire for self-fulfillment, namely, to the tendency for him to become actualized in what he is potentially. This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming. Example C: It’s been snowing for three days straight: The roads around here aren’t very safe for driving. How not to use a colon Incorrect example: The grocery list included: apples, grapes, milk, bread, and eggs. “The grocery list included” is not an independent clause, so it cannot be used with a colon—even if it is listing something after! Quick Tip: To make a dash in Microsoft Word, type two hypens Dashes (--) directly after a word, then type Dashes replace commas, semicolons, colons, and parentheses for the next word right after the two added emphasis, or an interruption/abrupt change of thought. -

Math Symbol Tables

APPENDIX A Math symbol tables A.1 Hebrew and Greek letters Hebrew letters Type Typeset \aleph ℵ \beth ℶ \daleth ℸ \gimel ℷ © Springer International Publishing AG 2016 481 G. Grätzer, More Math Into LATEX, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-23796-1 482 Appendix A Math symbol tables Greek letters Lowercase Type Typeset Type Typeset Type Typeset \alpha \iota \sigma \beta \kappa \tau \gamma \lambda \upsilon \delta \mu \phi \epsilon \nu \chi \zeta \xi \psi \eta \pi \omega \theta \rho \varepsilon \varpi \varsigma \vartheta \varrho \varphi \digamma ϝ \varkappa Uppercase Type Typeset Type Typeset Type Typeset \Gamma Γ \Xi Ξ \Phi Φ \Delta Δ \Pi Π \Psi Ψ \Theta Θ \Sigma Σ \Omega Ω \Lambda Λ \Upsilon Υ \varGamma \varXi \varPhi \varDelta \varPi \varPsi \varTheta \varSigma \varOmega \varLambda \varUpsilon A.2 Binary relations 483 A.2 Binary relations Type Typeset Type Typeset < < > > = = : ∶ \in ∈ \ni or \owns ∋ \leq or \le ≤ \geq or \ge ≥ \ll ≪ \gg ≫ \prec ≺ \succ ≻ \preceq ⪯ \succeq ⪰ \sim ∼ \approx ≈ \simeq ≃ \cong ≅ \equiv ≡ \doteq ≐ \subset ⊂ \supset ⊃ \subseteq ⊆ \supseteq ⊇ \sqsubseteq ⊑ \sqsupseteq ⊒ \smile ⌣ \frown ⌢ \perp ⟂ \models ⊧ \mid ∣ \parallel ∥ \vdash ⊢ \dashv ⊣ \propto ∝ \asymp ≍ \bowtie ⋈ \sqsubset ⊏ \sqsupset ⊐ \Join ⨝ Note the \colon command used in ∶ → 2, typed as f \colon x \to x^2 484 Appendix A Math symbol tables More binary relations Type Typeset Type Typeset \leqq ≦ \geqq ≧ \leqslant ⩽ \geqslant ⩾ \eqslantless ⪕ \eqslantgtr ⪖ \lesssim ≲ \gtrsim ≳ \lessapprox ⪅ \gtrapprox ⪆ \approxeq ≊ \lessdot -

Effective Punctuation

Effective Punctuation Contents: 1. Oxford commas 2. Parenthetic phrases 3. Independent clauses 4. Punctuation before or after quotation marks 5. Ellipses in quotations 6. Em dashes 7. One or two spaces after periods 8. When to capitalize after colons 1. Oxford Comma Writers disagree on whether lists of three or more should include a comma before the “and” (or “or”) and the last item in the list. Above all, consistency is key. If you do not know your reader's preference, choose one method and stick to it. Commas before the last “and” must be used when the final item in the list itself contains a conjunction (e.g., “He was charged with assault, battery, and breaking and entering.”) Option 1 Option 2 When the “Oxford Comma” is required The American flag is red, The American flag is red, You are charged with white and blue. white, and blue. trespassing, burglary, and assault and battery. 2. Parenthetic phrases Use commas to set off words and phrases that do not neatly fit into the main grammatical structure of the sentence. Nonrestrictive clauses are examples of parenthetic phrases. Unless the parenthetic phrase ends the sentence, there should always be a comma at the end of the parenthetic phrase. Do not use commas to set off phrases that, if removed, would change the meaning of the sentence, i.e., a restrictive clause. • Examples: o The Constitution, which was signed in 1787, is the supreme law of the land. o The Constitution, signed in 1787, is the supreme law of the land. o The judge, however, was not amused.