FAU Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Kitts Final Report

ReefFix: An Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Ecosystem Services Valuation and Capacity Building Project for the Caribbean ST. KITTS AND NEVIS FIRST DRAFT REPORT JUNE 2013 PREPARED BY PATRICK I. WILLIAMS CONSULTANT CLEVERLY HILL SANDY POINT ST. KITTS PHONE: 1 (869) 765-3988 E-MAIL: [email protected] 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 6 Glossary of Terms 7 Acronyms 10 Executive Summary 12 Part 1: Situational analysis 15 1.1 Introduction 15 1.2 Physical attributes 16 1.2.1 Location 16 1.2.2 Area 16 1.2.3 Physical landscape 16 1.2.4 Coastal zone management 17 1.2.5 Vulnerability of coastal transportation system 19 1.2.6 Climate 19 1.3 Socio-economic context 20 1.3.1 Population 20 1.3.2 General economy 20 1.3.3 Poverty 22 1.4 Policy frameworks of relevance to marine resource protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 23 1.4.1 National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) 23 1.4.2 National Physical Development Plan (2006) 23 1.4.3 National Environmental Management Strategy (NEMS) 23 1.4.4 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NABSAP) 26 1.4.5 Medium Term Economic Strategy Paper (MTESP) 26 1.5 Legislative instruments of relevance to marine protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 27 1.5.1 Development Control and Planning Act (DCPA), 2000 27 1.5.2 National Conservation and Environmental Protection Act (NCEPA), 1987 27 1.5.3 Public Health Act (1969) 28 1.5.4 Solid Waste Management Corporation Act (1996) 29 1.5.5 Water Courses and Water Works Ordinance (Cap. -

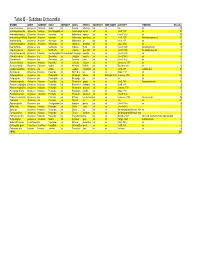

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia BINOMEN ORDER SUBORDER FAMILY SUBFAMILY GENUS SPECIES SUBSPECIES COMN_NAMES AUTHORITY SYNONYMS #Records Acanella arbuscula Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Acanella arbuscula n/a n/a n/a n/a 59 Acanthogorgia armata Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae n/a Acanthogorgia armata n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 95 Anthomastus agassizii Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 35 Anthomastus grandiflorus Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus grandiflorus n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 Anthomastus purpureus 37 Anthomastus sp. Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus sp. n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 1 Anthothela grandiflora Alcyonacea Scleraxonia Anthothelidae n/a Anthothela grandiflora n/a n/a (Sars, 1856) n/a 24 Capnella florida Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella florida n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya florida 44 Capnella glomerata Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella glomerata n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya glomerata 4 Chrysogorgia agassizii Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae Chrysogorgiidae Chrysogorgia agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1883) n/a 2 Clavularia modesta Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia modesta n/a n/a (Verrill, 1987) n/a 6 Clavularia rudis Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia rudis n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 1 Gersemia fruticosa Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Gersemia fruticosa n/a n/a Marenzeller, 1877 n/a 3 Keratoisis flexibilis Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Keratoisis flexibilis n/a n/a Pourtales, 1868 n/a 1 Lepidisis caryophyllia Alcyonacea n/a Isididae n/a Lepidisis caryophyllia n/a n/a Verrill, 1883 Lepidisis vitrea 13 Muriceides sp. -

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution by Peter J. Etnoyer1 and Stephen D. Cairns2 1. NOAA Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Charleston, SC 2. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC This annex to the U.S. Gulf of Mexico chapter in “The State of Deep‐Sea Coral Ecosystems of the United States” provides a list of deep‐sea coral taxa in the Phylum Cnidaria, Classes Anthozoa and Hydrozoa, known to occur in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). Deep‐sea corals are defined as azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species occurring in waters 50 m deep or more. Details are provided on the vertical and geographic extent of each species (Table 1). This list is adapted from species lists presented in ʺBiodiversity of the Gulf of Mexicoʺ (Felder & Camp 2009), which inventoried species found throughout the entire Gulf of Mexico including areas outside U.S. waters. Taxonomic names are generally those currently accepted in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and are arranged by order, and alphabetically within order by suborder (if applicable), family, genus, and species. Data sources (references) listed are those principally used to establish geographic and depth distribution. Only those species found within the U.S. Gulf of Mexico Exclusive Economic Zone are presented here. Information from recent studies that have expanded the known range of species into the U.S. Gulf of Mexico have been included. The total number of species of deep‐sea corals documented for the U.S. -

The Genetic Identity of Dinoflagellate Symbionts in Caribbean Octocorals

Coral Reefs (2004) 23: 465-472 DOI 10.1007/S00338-004-0408-8 REPORT Tamar L. Goulet • Mary Alice CofFroth The genetic identity of dinoflagellate symbionts in Caribbean octocorals Received: 2 September 2002 / Accepted: 20 December 2003 / Published online: 29 July 2004 © Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract Many cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea Introduction anemones) maintain a symbiosis with dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae). Zooxanthellae are grouped into The cornerstone of the coral reef ecosystem is the sym- clades, with studies focusing on scleractinian corals. biosis between cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea We characterized zooxanthellae in 35 species of Caribbean octocorals. Most Caribbean octocoral spe- anemones) and unicellular dinoñagellates commonly called zooxanthellae. Studies of zooxanthella symbioses cies (88.6%) hosted clade B zooxanthellae, 8.6% have previously been hampered by the difficulty of hosted clade C, and one species (2.9%) hosted clades B and C. Erythropodium caribaeorum harbored clade identifying the algae. Past techniques relied on culturing and/or identifying zooxanthellae based on their free- C and a unique RFLP pattern, which, when se- swimming form (Trench 1997), antigenic features quenced, fell within clade C. Five octocoral species (Kinzie and Chee 1982), and cell architecture (Blank displayed no zooxanthella cladal variation with depth. 1987), among others. These techniques were time-con- Nine of the ten octocoral species sampled throughout suming, required a great deal of expertise, and resulted the Caribbean exhibited no regional zooxanthella cla- in the differentiation of only a small number of zoo- dal differences. The exception, Briareum asbestinum, xanthella species. Molecular techniques amplifying had some colonies from the Dry Tortugas exhibiting zooxanthella DNA encoding for the small and large the E. -

Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the U. S. Caribbean Region: Depth And

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U. S. Caribbean Region: Depth and Geographical Distribution By Stephen D. Cairns1 1. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC An update of the status of the azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species that occur predominantly deeper than 50 m in the U.S. Caribbean territories is not given in this volume because of lack of significant additional data. However, an updated list of deep‐sea coral species in Phylum Cnidaria, Classes Anthozoa and Hydrozoa, from the Caribbean region (Figure 1) is presented below. Details are provided on depth ranges and known geographic distributions within the region (Table 1). This list is adapted from Lutz & Ginsburg (2007, Appendix 8.1) in that it is restricted to the U. S. territories in the Caribbean, i.e., Puerto Rico, U. S. Virgin Islands, and Navassa Island, not the entire Caribbean and Bahamian region. Thus, this list is significantly shorter. The list has also been reordered alphabetically by family, rather than species, to be consistent with other regional lists in this volume, and authorship and publication dates have been added. Also, Antipathes americana is now properly assigned to the genus Stylopathes, and Stylaster profundus to the genus Stenohelia. Furthermore, many of the geographic ranges have been clarified and validated. Since 2007 there have been 20 species additions to the U.S. territories list (indicated with blue shading in the list), mostly due to unpublished specimens from NMNH collections. As a result of this update, there are now known to be: 12 species of Antipatharia, 45 species of Scleractinia, 47 species of Octocorallia (three with incomplete taxonomy), and 14 species of Stylasteridae, for a total of 118 species found in the relatively small geographic region of U. -

Volume III of This Document)

4.1.3 Coastal Migratory Pelagics Description and Distribution (from CMP Am 15) The coastal migratory pelagics management unit includes cero (Scomberomous regalis), cobia (Rachycentron canadum), king mackerel (Scomberomous cavalla), Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus maculatus) and little tunny (Euthynnus alleterattus). The mackerels and tuna in this management unit are often referred to as ―scombrids.‖ The family Scombridae includes tunas, mackerels and bonitos. They are among the most important commercial and sport fishes. The habitat of adults in the coastal pelagic management unit is the coastal waters out to the edge of the continental shelf in the Atlantic Ocean. Within the area, the occurrence of coastal migratory pelagic species is governed by temperature and salinity. All species are seldom found in water temperatures less than 20°C. Salinity preference varies, but these species generally prefer high salinity. The scombrids prefer high salinities, but less than 36 ppt. Salinity preference of little tunny and cobia is not well defined. The larval habitat of all species in the coastal pelagic management unit is the water column. Within the spawning area, eggs and larvae are concentrated in the surface waters. (from PH draft Mackerel Am. 18) King Mackerel King mackerel is a marine pelagic species that is found throughout the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea and along the western Atlantic from the Gulf of Maine to Brazil and from the shore to 200 meter depths. Adults are known to spawn in areas of low turbidity, with salinity and temperatures of approximately 30 ppt and 27°C, respectively. There are major spawning areas off Louisiana and Texas in the Gulf (McEachran and Finucane 1979); and off the Carolinas, Cape Canaveral, and Miami in the western Atlantic (Wollam 1970; Schekter 1971; Mayo 1973). -

Tortugas Ecological Reserve

Strategy for Stewardship Tortugas Ecological Reserve U.S. Department of Commerce DraftSupplemental National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental National Ocean Service ImpactStatement/ Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management DraftSupplemental Marine Sanctuaries Division ManagementPlan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), working in cooperation with the State of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, proposes to establish a 151 square nautical mile “no- take” ecological reserve to protect the critical coral reef ecosystem of the Tortugas, a remote area in the western part of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The reserve would consist of two sections, Tortugas North and Tortugas South, and would require an expansion of Sanctuary boundaries to protect important coral reef resources in the areas of Sherwood Forest and Riley’s Hump. An ecological reserve in the Tortugas will preserve the richness of species and health of fish stocks in the Tortugas and throughout the Florida Keys, helping to ensure the stability of commercial and recreational fisheries. The reserve will protect important spawning areas for snapper and grouper, as well as valuable deepwater habitat for other commercial species. Restrictions on vessel discharge and anchoring will protect water quality and habitat complexity. The proposed reserve’s geographical isolation will help scientists distinguish between natural and human-caused changes to the coral reef environment. Protecting Ocean Wilderness Creating an ecological reserve in the Tortugas will protect some of the most productive and unique marine resources of the Sanctuary. Because of its remote location 70 miles west of Key West and more than 140 miles from mainland Florida, the Tortugas region has the best water quality in the Sanctuary. -

CNIDARIA Corals, Medusae, Hydroids, Myxozoans

FOUR Phylum CNIDARIA corals, medusae, hydroids, myxozoans STEPHEN D. CAIRNS, LISA-ANN GERSHWIN, FRED J. BROOK, PHILIP PUGH, ELLIOT W. Dawson, OscaR OcaÑA V., WILLEM VERvooRT, GARY WILLIAMS, JEANETTE E. Watson, DENNIS M. OPREsko, PETER SCHUCHERT, P. MICHAEL HINE, DENNIS P. GORDON, HAMISH J. CAMPBELL, ANTHONY J. WRIGHT, JUAN A. SÁNCHEZ, DAPHNE G. FAUTIN his ancient phylum of mostly marine organisms is best known for its contribution to geomorphological features, forming thousands of square Tkilometres of coral reefs in warm tropical waters. Their fossil remains contribute to some limestones. Cnidarians are also significant components of the plankton, where large medusae – popularly called jellyfish – and colonial forms like Portuguese man-of-war and stringy siphonophores prey on other organisms including small fish. Some of these species are justly feared by humans for their stings, which in some cases can be fatal. Certainly, most New Zealanders will have encountered cnidarians when rambling along beaches and fossicking in rock pools where sea anemones and diminutive bushy hydroids abound. In New Zealand’s fiords and in deeper water on seamounts, black corals and branching gorgonians can form veritable trees five metres high or more. In contrast, inland inhabitants of continental landmasses who have never, or rarely, seen an ocean or visited a seashore can hardly be impressed with the Cnidaria as a phylum – freshwater cnidarians are relatively few, restricted to tiny hydras, the branching hydroid Cordylophora, and rare medusae. Worldwide, there are about 10,000 described species, with perhaps half as many again undescribed. All cnidarians have nettle cells known as nematocysts (or cnidae – from the Greek, knide, a nettle), extraordinarily complex structures that are effectively invaginated coiled tubes within a cell. -

Investigation of the Microbial Communities Associated with the Octocorals Erythropodium

Investigation of the Microbial Communities Associated with the Octocorals Erythropodium caribaeorum and Antillogorgia elisabethae, and Identification of Secondary Metabolites Produced by Octocoral Associated Cultivated Bacteria. By Erin Patricia Barbara McCauley A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree of • Doctor of Philosophy Department of Biomedical Sciences Faculty of Veterinary Medicine University of Prince Edward Island Charlottetown, P.E.I. April 2017 © 2017, McCauley THESIS/DISSERTATION NON-EXCLUSIVE LICENSE Family Name: McCauley . Given Name, Middle Name (if applicable): Erin Patricia Barbara Full Name of University: University of Prince Edward Island . Faculty, Department, School: Department of Biomedical Sciences, Atlantic Veterinary College Degree for which Date Degree Awarded: , thesis/dissertation was presented: April 3rd, 2017 Doctor of Philosophy Thesis/dissertation Title: Investigation of the Microbial Communities Associated with the Octocorals Erythropodium caribaeorum and Antillogorgia elisabethae, and Identification of Secondary Metabolites Produced by Octocoral Associated Cultivated Bacteria. *Date of Birth. May 4th, 1983 In consideration of my University making my thesis/dissertation available to interested persons, I, :Erin Patricia McCauley hereby grant a non-exclusive, for the full term of copyright protection, license to my University, The University of Prince Edward Island: to archive, preserve, produce, reproduce, publish, communicate, convert into a,riv format, and to make available in print or online by telecommunication to the public for non-commercial purposes; to sub-license to Library and Archives Canada any of the acts mentioned in paragraph (a). I undertake to submit my thesis/dissertation, through my University, to Library and Archives Canada. Any abstract submitted with the . -

Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Northeast Region: Depth and Geographical Distribution (V

Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Northeast Region: Depth and Geographical Distribution (v. 2020) by David B. Packer1, Martha S. Nizinski2, Stephen D. Cairns3, 4 and Thomas F. Hourigan 1. NOAA Habitat Ecology Branch, Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Sandy Hook, NJ 2. NOAA National Systematics Laboratory Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 3. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 4. NOAA Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program, Office of Habitat Conservation, Silver Spring, MD This annex to the U.S. Northeast chapter in “The State of Deep-Sea Coral and Sponge Ecosystems of the United States” provides a revised and updated list of deep-sea coral taxa in the Phylum Cnidaria, Class Anthozoa, known to occur in U.S. waters from Maine to Cape Hatteras (Figure 1). Deep-sea corals are defined as azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species occurring in waters 50 meters deep or more. Details are provided on the vertical and geographic extent of each species (Table 1). This list is adapted from Packer et al. (2017) with the addition of new species and range extensions into Northeast U.S. waters reported through 2020, along with a number of species previously not included. No new species have been described from this region since 2017. Taxonomic names are generally those currently accepted in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and are arranged by order, then alphabetically by family, genus, and species. Data sources (references) listed are those principally used to establish geographic and depth distributions. The total number of distinct deep-sea corals documented for the U.S. -

Host-Microbe Interactions in Octocoral Holobionts - Recent Advances and Perspectives Jeroen A

van de Water et al. Microbiome (2018) 6:64 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0431-6 REVIEW Open Access Host-microbe interactions in octocoral holobionts - recent advances and perspectives Jeroen A. J. M. van de Water* , Denis Allemand and Christine Ferrier-Pagès Abstract Octocorals are one of the most ubiquitous benthic organisms in marine ecosystems from the shallow tropics to the Antarctic deep sea, providing habitat for numerous organisms as well as ecosystem services for humans. In contrast to the holobionts of reef-building scleractinian corals, the holobionts of octocorals have received relatively little attention, despite the devastating effects of disease outbreaks on many populations. Recent advances have shown that octocorals possess remarkably stable bacterial communities on geographical and temporal scales as well as under environmental stress. This may be the result of their high capacity to regulate their microbiome through the production of antimicrobial and quorum-sensing interfering compounds. Despite decades of research relating to octocoral-microbe interactions, a synthesis of this expanding field has not been conducted to date. We therefore provide an urgently needed review on our current knowledge about octocoral holobionts. Specifically, we briefly introduce the ecological role of octocorals and the concept of holobiont before providing detailed overviews of (I) the symbiosis between octocorals and the algal symbiont Symbiodinium; (II) the main fungal, viral, and bacterial taxa associated with octocorals; (III) the dominance of the microbial assemblages by a few microbial species, the stability of these associations, and their evolutionary history with the host organism; (IV) octocoral diseases; (V) how octocorals use their immune system to fight pathogens; (VI) microbiome regulation by the octocoral and its associated microbes; and (VII) the discovery of natural products with microbiome regulatory activities. -

Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Southeast Region: Depth and Geographic Distribution (V

Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Southeast Region: Depth and Geographic Distribution (v. 2020) by Thomas F. Hourigan1, Stephen D. Cairns2, John K. Reed3, and Steve W. Ross4 1. NOAA Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program, Office of Habitat Conservation, Silver Spring, MD 2. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 3. Cooperative Institute of Ocean Exploration, Research, and Technology, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, Florida Atlantic University, Fort Pierce, FL 4. Center for Marine Science, University of North Carolina, Wilmington This annex to the U.S. Southeast chapter in “The State of Deep-Sea Coral and Sponge Ecosystems in the United States” provides a list of deep-sea coral taxa in the Phylum Cnidaria, Classes Anthozoa and Hydrozoa, known to occur in U.S. waters from Cape Hatteras to the Florida Keys (Figure 1). Deep-sea corals are defined as azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species occurring in waters 50 meters deep or more. Details are provided on the vertical and geographic extent of each species (Table 1). This list is an update of the peer-reviewed 2017 list (Hourigan et al. 2017) and includes taxa recognized through 2019, including one newly described species. Taxonomic names are generally those currently accepted in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and are arranged by order, and alphabetically within order by family, genus, and species. Data sources (references) listed are those principally used to establish geographic and depth distribution. Figure 1. U.S. Southeast region delimiting the geographic boundaries considered in this work. The region extends from Cape Hatteras to the Florida Keys and includes the Jacksonville Lithoherms (JL), Blake Plateau (BP), Oculina Coral Mounds (OC), Miami Terrace (MT), Pourtalès Terrace (PT), Florida Straits (FS), and Agassiz/Tortugas Valleys (AT).