1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asterism: Volume 2

ASTERISM: VOLUME 2 2018 Asterism: An Undergraduate Literary Journal Staff is published anually by The Ohio State Uni- versity at Lima. Senior Editors *** All poems and stories in the magazine are Jenna Bush works of imagination. Ashley Meihls Address all correspondence to: Galvin Hall 401A Editors 4240 Campus Dr. *** Lima, OH 45804 Katie Marshall Victoria Sullivan Visit our website: Mattea Rolsten lima.osu.edu/asterism Andrea Morales Jacob Short Published 2018 Cover Art: Faculty Advisors “Raindrops” by Jessy Gilcher *** Beth Sutton-Ramspeck Doug Sutton-Ramspeck Asterism - I Table of Contents A Note to Our Readers V -273.15 °C ............................................................. Emma DePanise Poetry 8 Holy Man ............................................................. Deon Robinson Poetry 9 Starry Eyes ................................................... Hannah Schotborgh Poetry 10 Untitled ....................................................................... Riley Klaus Art 12 Bones ..................................................................... Angela Kramer Poetry 13 Blinker ....................................................................... Bryan Miller Fiction 15 Still Water ............................................................ Trevor Bashaw Poetry 19 Hearsay .................................................................... Noah Corbett Poetry 21 Para Mi Alma ........................................................... Asalia Arauz Poetry 26 Amaryllis ................................................................ -

21 Stars Review: the Complete Poetry and Prose Letitia Trent and Chris R

21 Stars Review: The complete poetry and prose Letitia Trent and Chris R. E. Wells, editors Copyright 2009 Published by Sundress Publications All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of contributors. Printed in the United States of America Book Design by Chris Wells, Lori Scoby, and Jeremy Porter Cover based on a photo by Paul Baker Sundress Publications / 21 Stars Review [email protected] or [email protected] * This publication is free. However, the editors ask that everyone who obtains a copy make a donation to Grandma’s Gifts, an antipoverty and pro-literacy charity benefitting the Appalachian region of the United States. Please go to http://www.grandmasgifts.org to read about the charity and make your donation. Thank you. Table of Contents I. TEXT ……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 FJ Bergmann, “Pilgrimage ”…………………………………………………………………… 9 “Solitude ”……………………………………………………………………… …… 10 “Waterfall ”………………………………………………………………………… 11 Amanda Silbernagel, “below freezing ”……………………………………………………… 12 Glenn Bach, “from Atlas Peripatetic ”………………………………………………………… 13 Becky Peterson, “Defensive Drawing ”……………………………………………………… 15 Harry Johnson, “Next Time, a Rabbit ”……………………………………………………… 17 Gilad Elbom, “A Beginning ”……………………………………………… ………………… 19 Nicol ás Mansito III, “The Escape Artist ”…………………………………………………… 21 William Yazbec, “Midwestern Flashers ”……………………………………………………… 23 Laura Wetherington, “This field is a blazon ”………………………………………………… 38 “I’m rig ht about time ”……………………………………………………………… 39 Louis -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

Read Book Just What I Needed Ebook Free Download

JUST WHAT I NEEDED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lorelei James | 368 pages | 02 Aug 2016 | Signet Book | 9780451477569 | English | United States Just What I Needed PDF Book Retrieved 19 September Funtime New Musical Express. Get promoted. Hello Again Thesaurus Entries near needed nectar nectars need needed needful needfulness needfuls See More Nearby Entries. Carlisle - 2m 4f - 2m 4f - 2m - 2m 1f - 2m 1f - 3m 2f - 2m 4f - 2m 4f View all races at Carlisle. Full Terms apply. Summary - Data does not include this horse 10 runs, 1 win 1 horse , 2 placed, 7 unplaced. We're gonna stop you right there Literally How to use a word that literally drives some pe The Cars. Bye Bye Love 5. Save Cancel. Down Boys. ATR Future Form Summary - Data does not include this horse 11 runs, 0 wins 0 horses , 2 placed, 9 unplaced Next time out 6 runs, 0 wins, 1 placed, 5 unplaced Class analysis 0 runs up in class, 0 wins, 0 placed, 0 unplaced Ratings check Highest winning OR: 0; Highest placed OR: 42 Index value from 6 horses. ATR Future Form Summary - Data does not include this horse 9 runs, 1 win 1 horse , 3 placed, 5 unplaced Next time out 4 runs, 1 win, 1 placed, 2 unplaced Class analysis 0 runs up in class, 0 wins, 0 placed, 0 unplaced Ratings check Highest winning OR: 57; Highest placed OR: 58 Index value from 4 horses. Save Word. Summary - Data does not include this horse 13 runs, 0 wins 0 horses , 2 placed, 11 unplaced. Next time out 6 runs, 0 wins, 1 placed, 5 unplaced. -

The Comment, September 24, 1987

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University The ommeC nt Campus Journals and Publications 1987 The ommeC nt, September 24, 1987 Bridgewater State College Volume 65 Number 1 Recommended Citation Bridgewater State College. (1987). The Comment, September 24, 1987. 65(1). Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/comment/603 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The Comment Bridgewater State College September 24, 1987 Vol. LXV No. 1 Bridgewater, MA Changes are in store for next year's freshman applicants By Chris Perra in which a student can apply. two years, this cap on admissions The College will inform students will be continued in an effort to Students applying to of acceptance or rejection between reduct the student to faculty ratio. Bridgewater next year will April 1 and April 15; the student, As it stands now, the ratio is encounter a system very different in turn. must notify the College approximately 23: 1. The ideal from the one present students as to his intention by May 1. In ratio that is being worked towards met. order to give a student a chance to is 17:1. Prospective students will express him or herself in works, have to submit a writing sample separate from their academic President Indelicato stated that ·in addition to their application. credentials, the College will is was the administration's hope This essay ,on an as yet undecided institute a system for that the . admissions topic, will be reviewed by the administering voluntary competitiveness level will be admissions office. -

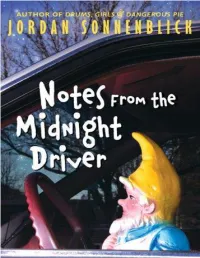

Notes from the Midnight Driver

Notes From the Midnight Driver Jordan Sonnenblick SCHOLASTIC INC. New York Toronto London Auckland Sydney Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong Buenos Aires To my grandfather, Solomon Feldman, who inspired this book, and to the memory of my father, Dr. Harvey Sonnenblick, who loved it Table of Contents Title Page Dedication May Last September Gnome Run The Wake-Up Day Of The Dork-Wit My Day In Court Solomon Plan B Laurie Meets Sol Sol Gets Interested Half An Answer Happy Holidays The Ball Falls Happy New Year! Enter The Cha-Kings Home Again Am I A Great Musician, Or What? A Night For Surprises Darkness The Valentine’s Day Massacre Good Morning, World! The Mission The Saints Go Marchin’ In The Work Of Breathing Peace In My Tribe Finale Coda The Saints Go Marchin’ In Again Thank you Notes About the Author Interview Sneak Peek Copyright May Boop. Boop. Boop. I’m sitting next to the old man’s bed, watching the bright green line spike and jiggle across the screen of his heart monitor. Just a couple of days ago, those little mountains on the monitor were floating from left to right in perfect order, but now they’re jangling and jerking like maddened hand puppets. I know that sometime soon, the boops will become one long beep, the mountains will crumble into a flat line, and I will be finished with my work here. I will be free. LAST SEPTEMBER GNOME RUN It seemed like a good idea at the time. Yes, I know everybody says that—but I’m serious. -

Analysis of Alternative Rock Scene Through Feminist Standpoint

ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVE ROCK SCENE THROUGH FEMINIST STANDPOINT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ELİF CEREN BOSTANCI KUTLU IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF GENDER AND WOMEN’S STUDIES MAY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Ayşe Saktanber Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Fatma Yıldız Ecevit Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Nilay Çabuk Kaya (Ankara Uni., SOS) Prof. Dr. Fatma Yıldız Ecevit (METU, SOC) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe İdil Aybars (METU, SOC) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Elif Ceren Bostancı Kutlu Signature: iii ABSTRACT ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVE ROCK SCENE THROUGH FEMINIST STANDPOINT Bostancı Kutlu, Elif Ceren M.S., Department of Gender and Women Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Fatma Yıldız Ecevit May 2020, 199 pages Music, as a social field, is affected by the patriarchal practices which are relevant in society. -

The Projectionist

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-16-2008 The Projectionist David Parker Jr. University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Parker, David Jr., "The Projectionist" (2008). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 662. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/662 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Projectionist A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre, and Communication Arts Creative Writing By David Parker Jr. B.A. Hampden-Sydney College, 1994 May, 2008 For the Angel in the fountain. ii Acknowledgments So many people helped me bring forward this body of work – and to them all I offer my sincerest thanks. First, of course, to my family for their unfailing support and long distance power hours – great love and respect to the tribes of Parker, Adams, Sparks, and Featherston. -

A History of the Maple Leaf Bar

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 Native Music And Regular Gigs: A History Of The Maple Leaf Bar Pieter Frank Kossen University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kossen, Pieter Frank, "Native Music And Regular Gigs: A History Of The Maple Leaf Bar" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 873. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/873 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIVE MUSIC AND REGULAR GIGS: A HISTORY OF THE MAPLE LEAF BAR A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Southern Studies Degree University of Mississippi Pieter Frank Kossen December 2017 ©Copyright Pieter Frank Kossen December 1, 2017 All Rights Reserved Abstract The purpose of this work is to construct a history of the Maple Leaf Bar in New Orleans, Louisiana in order to determine its place and establish its importance in the musical history of New Orleans. Opened in early 1974, the Maple Leaf Bar is the oldest continually- functioning music club in the city of New Orleans outside of the French Quarter, and is accorded a share of the credit for the current popularity in New Orleans of the roots music of New Orleans and Louisiana. This will be accomplished by identifying and examining common traits the Maple Leaf Bar shares with prominent clubs from New Orleans’s history, and also by identifying traits that make the Maple Leaf Bar exceptional in this history. -

Politics As Unusual: Washington, D.C

Abstract Title of Dissertation: POLITICS AS UNUSUAL: WASHINGTON, D.C. HARDCORE PUNK 1979-1983 AND THE POLITICS OF SOUND Shayna L Maskell, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Nancy Struna, Chair, Department of American Studies During the creative and influential years between 1979 and 1983, hardcore punk was not only born — a mutated sonic stepchild of rock n’ roll, British and American punk — but also evolved into a uncompromising and resounding paradigm of and for DC youth. Through the revelatory music of DC hardcore bands like Bad Brains, Teen Idles, Minor Threat, State of Alert, Government Issue and Faith a new formulation of sound, and a new articulation of youth, arose: one that was angry, loud, fast, and minimalistic. With a total of only ten albums between all five bands in a mere five years, DC hardcore cemented a small yet significant subculture and scene. This project considers two major components of this music: aesthetics and the social politics that stem from those aesthetics. By examining the way music communicates — facets like timbre, melody, rhythm, pitch, volume and dissonance — while simultaneously incorporating an analysis of hardcore’s social context — including the history of music’s cultural canons, as well as the specific socioeconomic, racial and gendered milieu in which music is generated, communicated and responded to —this dissertation attempts to understand how hardcore punk conveys messages of social and cultural politics, expressly representations of race, class and gender. In doing so, this project looks at how DC hardcore (re)contextualizes and (re)imagines the social and political meanings created by and from sound. -

TQS Interview Transcription

Interview Transcriptions: The Q Sides So VERO pretty much knows like why I’m here but you know when I went to the event, I was really moved by it and I had originally intended on doing my year long research project on women and the role of women, and the use of women on lowriders. But then I went to your event, and I just fell in love with it and I have a lot of QPOC friends, and as an ally I find that visibility for queer Latinos and also for people who low ride is really important to me, and then the fact that you guys put them together in one thing was so incredible and mindblowing to me, so I really wanted to use you guys as an avenue to find the population and kind of work with this community and give visibility and highlight the voices and the lives of queer lowriders and people who identify with all these identifications so thank you for allowing me to interview you. I do have this consent form. VERO sure It just had my contact information and my research advisors contact information [break down for pseudonym] VERO If you were to…mention our names not just my name when you give credit. That is the only thing I would say. The Q Sides is KARI, DJ BROWN AMY, and myself. [chatter] So I guess we can start at kind of the three of your creative process in creating this project. I know you told me about the grant that Galería had and that process and how you came together as a team to do The Q Sides. -

Grierson, Kimpel-It All Begins with the Music.Pdf

It All Begins with the Music: Developing Successful Artists and Careers for the New Music Business Don Grierson and Dan Kimpel Course Technology PTR A part of Cengage Learning Australia . Brazil . Japan . Korea . Mexico . Singapore . Spain . United Kingdom . United States It All Begins with the Music: Developing C 2009 Don Grierson and Dan Kimpel Successful Artists and Careers for the ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein New Music Business may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used in any form or by any means Don Grierson and Dan Kimpel graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, Publisher and General Manager, Course recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information Technology PTR: Stacy L. Hiquet networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without Associate Director of Marketing: the prior written permission of the publisher. Sarah Panella Manager of Editorial Services: Heather Talbot For product information and technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706 Marketing Manager: Mark Hughes Executive Editor: Mark Garvey For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests online at cengage.com/permissions Project Editor: Kim Benbow Further permissions questions can be emailed to Editorial Services Coordinator: Jen [email protected] Blaney Copy Editor: Andy Saff