A History of the Maple Leaf Bar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neil Foster Spiritualises Carole Lateman Lets Us Into Her Life John

October 2014 October 81 ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK Cosimo Matassa & Senator Jones, Sea Saint Studios, New Orleans, 04-05-79 © Paul Harris Dominique, our man in la belle France, wishes to write an extensive biography of Cosimo to be published in future issues so here is Paul’s picture to confirm we aren’t ignoring Cosimo’s passing. Neil Foster spiritualises Carole Lateman lets us into her life John Howard rocks it up in Las Vegas Keith gets to know more about Iain Terry Soul Kitchen, Jazz Junction, Blues Rambling And more... 1 The recent piece by Tony Papard has spurred me to write a little about the paranormal and the arguments both for and against it. First, an experience (concerning a communication from the dead) that my mother had. She once told me that she often used to wake up in the middle of the night to see her late father standing by the bed, not as a vague shape, but as real-looking as if he were still alive. I asked her if she was frightened by the apparition and she replied, “Well, I didn't like it but I knew he wasn't real, so I pulled the clothes over my head and went back to sleep.” So, did she really see her dead father standing by the bed or...? Obviously, she could never “prove” that it happened as she described and no one else could prove that it didn't. However, there is a way around this logical impasse. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Neil Foster Carries on Hating Keith Listens To

April 2017 April 96 In association with "AMERICAN MUSIC MAGAZINE" ALL ARTICLES/IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT OF THEIR RESPECTIVE AUTHORS. FOR REPRODUCTION, PLEASE CONTACT ALAN LLOYD VIA TFTW.ORG.UK Chuck Berry, Capital Radio Jazzfest, Alexandra Palace, London, 21-07-79, © Paul Harris Neil Foster carries on hating Keith listens to John Broven The Frogman's Surprise Birthday Party We “borrow” more stuff from Nick Cobban Soul Kitchen, Jazz Junction, Blues Rambling And more.... 1 2 An unidentified man spotted by Bill Haynes stuffing a pie into his face outside Wilton’s Music Hall mumbles: “ HOLD THE THIRD PAGE! ” Hi Gang, Trust you are all well and as fluffy as little bunnies for our spring edition of Tales From The Woods Magazine. WOW, what a night!! I'm talking about Sunday 19th March at Soho's Spice Of Life venue. Charlie Gracie and the TFTW Band put on a show to remember, Yes, another triumph for us, just take a look at the photo of Charlie on stage at the Spice, you can see he was having a ball, enjoying the appreciation of the audience as much as they were enjoying him. You can read a review elsewhere within these pages, so I won’t labour the point here, except to offer gratitude to Charlie and the Tales From The Woods Band for making the evening so special, in no small part made possible by David the excellent sound engineer whom we request by name for our shows. As many of you have experienced at Rock’n’Roll shows, many a potentially brilliant set has been ruined by poor © Paul Harris sound, or literally having little idea how to sound up a vintage Rock’n’Roll gig. -

Cycle2 Playlist

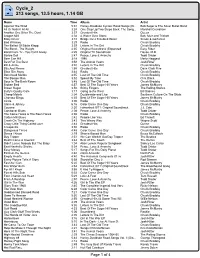

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Unit Title: It's About Time – the Power of Folk Music

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Music 7th Grade Unit Title: It’s About Time – The Power of Folk Music Non-Ensemble Based INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Denver Public Schools Regina Dunda Metro State University of Denver Carla Aguilar, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Falcon School District Harriet G. Jarmon, PhD Center School District Kate Newmeyer Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Music Grade Level 7th Grade Course Name/Course Code General Music (Non-Ensemble Based) Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Expression of Music 1. Perform music in three or more parts accurately and expressively at a minimal level of level 1 to 2 on the MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.1 difficulty rating scale 2. Perform music accurately and expressively at the minimal difficulty level of 1 on the difficulty rating scale at MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.2 the first reading individually and as an ensemble member 3. Demonstrate understanding of modalities MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.3 2. Creation of Music 1. Sequence four to eight measures of music melodically and rhythmically MU09-GR.7-S.2-GLE.1 2. -

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

Southeast Texas: Reviews Gregg Andrews Hothouse of Zydeco Gary Hartman Roger Wood

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director As the Institute for riety of other great Texas musicians. Proceeds from the CD have the History of Texas been vital in helping fund our ongoing educational projects. Music celebrates its We are very grateful to the musicians and to everyone else who second anniversary, we has supported us during the past two years. can look back on a very The Institute continues to add important new collections to productive first two the Texas Music Archives at SWT, including the Mike Crowley years. Our graduate and Collection and the Roger Polson and Cash Edwards Collection. undergraduate courses We also are working closely with the Texas Heritage Music Foun- on the history of Texas dation, the Center for American History, the Texas Music Mu- music continue to grow seum, the New Braunfels Museum of Art and Music, the Mu- in popularity. The seum of American Music History-Texas, the Mexico-North con- Handbook of Texas sortium, and other organizations to help preserve the musical Music, the definitive history of the region and to educate the public about the impor- encyclopedia of Texas tant role music has played in the development of our society. music history, which we At the request of several prominent people in the Texas music are publishing jointly industry, we are considering the possibility of establishing a music with the Texas State Historical Association and the Texas Music industry degree at SWT. This program would allow students Office, will be available in summer 2002. The online interested in working in any aspect of the music industry to bibliography of books, articles, and other publications relating earn a college degree with specialized training in museum work, to the history of Texas music, which we developed in cooperation musical performance, sound recording technology, business, with the Texas Music Office, has proven to be a very useful tool marketing, promotions, journalism, or a variety of other sub- for researchers. -

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

TOM MALONEY and TOM HALL a Tribute to Four Important St

TOM MALONEY AND TOM HALL A Tribute to Four Important St. Louisans, BLUESWEEK Review in Pictures, An Essay by Alonzo Townsend, The Application Window Opens for the St. Louis/IBC Road to Memphis, plus: CD Review, Discounts for Members and more... THE BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE SAINT LOUIS BLUES SOCIETY July/August 2014 Number 69 July/August 2014 Number 69 Officers Chairperson BLUESLETTER John May The Bi-Monthly Magazine of the St. Louis Blues Society Vice Chairperson The St. Louis Blues Society is dedicated to preserving and perpetuating blues music in Jeremy Segel-Moss and from St. Louis, while fostering its growth and appreciation. The St. Louis Blues Society provides blues artists the opportunity for public performance and individual Treasurer improvement in their field, all for the educational and artistic benefit of the general public. Jerry Minchey Legal Counsel Charley Taylor CELEBRATING 30 YEARS Secretary Lynn Barlar OF SUPPORTING BLUES MUSIC IN ST LOUIS Communications Dear Blues Lovers, Mary Kaye Tönnies Summer is in full swing in St. Louis.Festivals, neighborhood events and patios filled with Board of Directors music are kickin’ all over the City. Bluesweek, over Memorial Day Weekend, was a big hit for Ridgley "Hound Dog" Brown musicians and fans alike. Check out some of the pictures from the weekend on page 11. Thanks to Bernie Hayes everyone who helped make Bluesweek a success! Glenn Howard July means the opening of applications for bands and solo/duo acts who want to be involved Rich Hughes in this year’s International Blues Challenge. Last year we had a fantastic group of bands and solo/ Greg Hunt duo acts competing to go to Memphis. -

Son Sealsseals 1942-2004

January/February 2005 Issue 272 Free 30th Anniversary Year www.jazz-blues.com SonSon SealsSeals 1942-2004 INSIDE... CD REVIEWS FROM THE VAULT January/February 2005 • Issue 272 Son Seals 1942-2004 The blues world lost another star Son’s 1973 debut recording, “The when W.C. Handy Award-winning and Published by Martin Wahl Son Seals Blues Band,” on the fledging Communications Grammy-nominated master Chicago Alligator Records label, established him bluesman Son Seals, 62, died Mon- as a blazing, original blues performer and Editor & Founder Bill Wahl day, December 20 in Chicago, IL of composer. Son’s audience base grew as comlications with diabetes. The criti- he toured extensively, playing colleges, Layout & Design Bill Wahl cally acclaimed, younger generation clubs and festivals throughout the coun- guitarist, vocalist and songwriter – try. The New York Times called him “the Operations Jim Martin credited with redefining Chicago blues most exciting young blues guitarist and Pilar Martin for a new audience in the 1970s – was singer in years.” His 1977 follow-up, Contributors known for his intense, razor-sharp gui- “Midnight Son,” received widespread ac- Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, tar work, gruff singing style and his claim from every major music publica- Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, charismatic stage presence. Accord- tion. Rolling Stone called it ~one of the David McPherson, Tim Murrett, ing to Guitar World, most significant blues Peanuts, Mark Smith, Duane “Seals carves guitar albums of the decade.” Verh and Ron Weinstock. licks like a chain On the strength of saw through solid “Midnight Son,” Seals Check out our new, updated web oak and sings like began touring Europe page. -

Peter Novelli Peternovelli.Com

Peter Novelli peternovelli.com Guitarist / singer / songwriter Peter Novelli is based in New Orleans. The Peter Novelli Band plays Louisiana roots and blues, a blend of blues-rock-R&B-funk with some zydeco-cajun influences. Novelli’s CD Louisiana Roots & Blues (June 12 release) with his core rhythm section Darryl White (drums, formerly w/ Tab Benoit and Chris Thomas King), Chris Chew (bass, North Mississippi Allstars), Joe Krown (B3 and piano, formerly w/ late Gatemouth Brown), and special guests Chubby Carrier (Grammy-winning zydeco accordionist), Chris Thomas King (lap slide guitar, Grammy “Oh Brother, Where Art Thou”), Shamarr Allen (trumpet) and Elaine and Lisa Foster on vocals. Novelli’s debut CD, produced by bassist David Hyde, hit the charts within a month of release and gathered widespread critical acclaim. His originals, with a few selected covers, made a journey through Louisiana-American blues-roots music. Guests include Dr. John, Paul Barrere, Augie Meyers, the late Gatemouth Brown’s rhythm section, and top Lousiana musicians. The CD includes an historical Tribute To Slim Harpo, with members of Harpo’s band including James Johnson, and interviews with Johnson, the late Raful Neal and “Big” Johnny Thomassie. Novelli started violin at age 6, picked up guitar at 14 after hearing a BB King record. The intensity, passion and raw emotional content of some of the blues masters (black and white, American and British) stuck in his ear and that is what drives him to this day. He likes to combine this feel with harmonic ideas of jazz, the relentless groove of zydeco, and just about any cool and unusual style of music or rhythm that works. -

By David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents

Copyright by David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Chapter INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 1. JAZZ AND JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS: A BACKGROUND ................ 3 2. ECONOMICS AND POPULARITY OF MODERN JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS 8 3. MODERN JAZZ RECORDINGS IN NEW ORLEANS …..................... 22 4. ALL FOR ONE RECORDS AND HAROLD BATTISTE: A CASE STUDY …................................................................................................................. 38 CONCLUSION …........................................................................................ 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY ….................................................................................... 50 i 1 Introduction Modern jazz has always been artistically alive and creative in New Orleans, even if it is not as well known or commercially successful as traditional jazz. Both outsiders coming to New Orleans such as Ornette Coleman and Cannonball Adderley and locally born musicians such as Alvin Battiste, Ellis Marsalis, and James Black have contributed to this music. These musicians have influenced later players like Steve Masakowski, Shannon Powell, and Johnny Vidacovich up to more current musicians like Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, and Christian Scott. There are multiple reasons why New Orleans modern jazz has not had a greater profile. Some of these reasons relate to the economic considerations of modern jazz. It is difficult for anyone involved in modern jazz, whether musicians, record