NAR : Winter 95

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic N Ewspa Per in Continuous Publication Friday, January 21, 1983 Naming Latvian a Cardinal Called

O OD Inside storal d raft an alysis zpa l statem ents, U .S. draft show consistency, says archbishop o to reducing armaments. NNETH J. DOYLE special committee of U.S. bishops visit to Rome for meetings Jan. 18- statements indicates that on the CO H drafting the document. 19 with Vatican officials and two basic points of the American If anything, the papal thinking -c H •< draft there is a meeting of the seems in certain respects to lean > CO i CITY (NC) — “If anyone thinks that the draft delegations of several European esignate Joseph is off the papal mark, I would hierarchies to discuss the draft minds. toward greater restrictions invite the person to show us document. These two points are: regarding nuclear issues than the CD f Chicago expresses American draft. 3D his work when asked where,” says Archbishop The archbishop’s confidence is • Acceptance of the just war to > can thinks of the U .S. Bernardin when questioned about supported by the text of the draft theory coupled with the belief that The draft of the U.S. bishops fNJ X t pastoral on nuclear criticisms that the U.S. bishops' pastoral which shows a striking the theory virtually negates use of recognizes the validity of the just draft is incompatible with papal consistency with statements by nuclear weapons. war theory, even in today’s an input has been thinking. Pope John Paul II. • The acceptability of nuclear nuclear age. It describes that ositive and suppor- Archbishop Bernardin was A study of the d ra ft in deterrence but only coupled to theory and the moral choice of e man who heads the interviewed by NC News during a juxtaposition with papal strong bilateral efforts at (Continued on page 2) Pennsylvania's P riest dies largest weekly Fr. -

The Creative Life of 'Saturday Night Live' Which Season Was the Most Original? and Does It Matter?

THE PAGES A sampling of the obsessive pop-culture coverage you’ll find at vulture.com ost snl viewers have no doubt THE CREATIVE LIFE OF ‘SATURDAY experienced Repetitive-Sketch Syndrome—that uncanny feeling NIGHT LIVE’ WHICH Mthat you’re watching a character or setup you’ve seen a zillion times SEASON WAS THE MOST ORIGINAL? before. As each new season unfolds, the AND DOES IT MATTER? sense of déjà vu progresses from being by john sellers 73.9% most percentage of inspired (A) original sketches season! (D) 06 (B) (G) 62.0% (F) (E) (H) (C) 01 1980–81 55.8% SEASON OF: Rocket Report, Vicki the Valley 51.9% (I) Girl. ANALYSIS: Enter 12 51.3% new producer Jean Doumanian, exit every 08 Conehead, Nerd, and 16 1975–76 sign of humor. The least- 1986–87 SEASON OF: Samurai, repetitive season ever, it SEASON OF: Church Killer Bees. ANALYSIS: taught us that if the only Lady, The Liar. Groundbreaking? breakout recurring ANALYSIS: Michaels Absolutely. Hilarious? returned in season 11, 1990–91 character is an unfunny 1982–83 Quite often. But man-child named Paulie dumped Billy Crystal SEASON OF: Wayne’s SEASON OF: Mr. Robinson’s unbridled nostalgia for Herman, you’ve got and Martin Short, and Neighborhood, The World, Hans and Franz. SNL’s debut season— problems that can only rebuilt with SNL’s ANALYSIS: Even though Whiners. ANALYSIS: Using the second-least- be fixed by, well, more broadest ensemble yet. seasons 4 and 6 as this is one of the most repetitive ever—must 32.0% Eddie Murphy. -

The Artillery of Critique Versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing up to Propaganda, 1990-1999

THE ARTILLERY OF CRITIQUE VERSUS THE GENERAL UNCRITICAL CONSENSUS: STANDING UP TO PROPAGANDA, 1990-1999 by Andrew Alexander Monti Master of Arts, York University, Toronto, Canada, 2013 Bachelor of Science, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy, 2005 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Joint Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2018 © Andrew Alexander Monti, 2018 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The Artillery of Critique versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing Up to Propaganda, 1990-1999 Andrew Alexander Monti Doctor of Philosophy Communication and Culture Ryerson University, 2018 In 2011, leading comedy scholars singled-out two shortcomings in stand-up comedy research. The first shortcoming suggests a theoretical void: that although “a number of different disciplines take comedy as their subject matter, the opportunities afforded to the inter-disciplinary study of comedy are rarely, if ever, capitalized on.”1 The second indicates a methodological void: there is a “lack of literature on ‘how’ to analyse stand-up comedy.”2 This research project examines the relationship between political consciousness and satirical humour in stand-up comedy and attempts to redress these two shortcomings. -

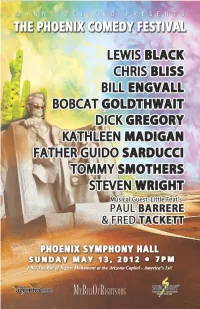

Final Final Front Pcf Program

Wishes to give special Gratefully acknowledges major acknowledgement to support for this event from This project would not Building Integrity Since 1890 have been possible without their ongoing support Proud to Honor the Tenets of Our Freedom Gratefully acknowledges major Gratefully acknowledges major support for this event from support for this event from find your inspiration 5700 East McDonald Drive Scottsdale, Arizona 85253 Reservation: 480-948-2100 www.sanctuaryaz.com The Artists The Artists Lewis Black Kathleen Madigan George Carlin, Larry King and Jules Feiffer love Lewis In her 22 year career, Kathleen Madigan has never been Black. They love him because his insights and love/hate hotter. With her recent Showtime special, “Gone relationship with America are brilliantly expressed in his Madigan,” in constant rotation and the DVD-CD of the concerts and TV appearances worldwide. How can you special topping the Amazon and iTunes charts, Madigan not love a man who says, “Republicans are a party with has the entire year booked with over 100 theater gigs bad ideas and Democrats are a party with no ideas.” Will across the country and numerous television appearances. Rogers would have been proud. Bill Engvall Father Guido Sarducci (Don Novello) It’s Bill Engvall’s ability for sharing the humor in Don Novello is a writer, film director, producer, actor, everyday situations that has made him one of the top and comedian, best known for his many appearances as comedians today. Best known for as part of the Father Guido Sarducci on “Saturday Night Live”, a role enormously successful Blue Collar Comedy Tour, Bill’s he reprised most recently on “The Colbert Report.” His also starred in his own self-titled sitcom for TBS, had books of replies by the famous and powerful to letters he numerous television specials and film appearances, and is wrote as another of his creations, Lazlo Toth, remain currently headlining his own solo comedy tour. -

South East West Midwest

NC State (12) Arizona St. (10) Kansas St. (9) Kentucky (8) Texas (7) Massachusetts (6) Saint Louis (5) Louisville (4) Duke (3) Michigan (2) Wichita St. (1) Florida (1) Kansas (2) Syracuse (3) UCLA (4) VCU (5) Ohio St. (6) New Mexico (7) Colorado (8) Pittsburgh (9) Stanford (10) 1. Zach Galifianakis, 1. Jimmy Kimmel, 1. Eric Stonestreet, 1. Ashley Judd, 1. Walter Cronkite, 1. Bill Cosby, 1. Enrique Bolaños, 1. Diane Sawyer, 1. Richard Nixon, 37th 1. Gerald Ford, 38th 1. Riley Pitts, Medal 1. Marco Rubio, U.S. 1. Alf Landon, former 1. Ted Koppel, TV 1. Jim Morrison, 1. Patch Adams, 1. Dwight Yoakam, 1. Penny Marshall, 1. Robert Redford, 1. Gene Kelly, 1. Herbert Hoover, actor, "The Hangover" host, "Jimmy Kimmel actor, "Modern Family" actress, "Kiss the Girls" former anchorman, actor/comedian, "The former president of news anchor President of the U.S. President of the U.S. of Honor recipient Senator, Florida Kansas governor, 1936 journalist, "Nightline" musician, The Doors doctor/social activist country music director/producer, "A actor, “Butch Cassidy actor/dancer/singer, 31st President of the 2. John Tesh, TV Live!" 2. Kirstie Alley, 2. Mitch McConnell, CBS Evening News Cosby Show" Nicaragua 2. Sue Grafton, 2. Charlie Rose, 2. James Earl Jones, 2. Shirley Knight, 2. Bob Graham, presidential candidate 2. Dick Clark, 2. Francis Ford 2. Debbie singer-songwriter League of Their Own" and the Sundance Kid” "Singin' in the Rain" U.S. composer 2. Kate Spade, actress, "Cheers" U.S. Senator, Kentucky 2. Matthew 2. Richard Gere, actor, 2. Robert Guillaume, author, “A is for Alibi” talk-show host, actor, "The Great actress, "The Dark at former U.S. -

The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980)

Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) By Lawrence Murray 1 Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) ABSTRACT The image of the broadcast news journalist is one that we can identify with on a regular basis. We see the news as an opportunity to be engaged in the world at large. Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” brought a different take on the image of the journalist: one that was a satire on its head, but a criticism of news culture as a whole. This article looks at the first five seasons of Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” and the image of the journalist portrayed by the SNL cast members serving as cast members from 1975 (Chevy Chase) until 1980 (Bill Murray and Jane Curtin). This article will show how the anchors’ style and substance does more than tell jokes about the news. The image of the journalist portrayed through the 1970s version of “Weekend Update” is mostly a negative one; while it acknowledges the importance of news and information by being a staple of the show, it ultimately mocks the news and the journalists who are prominently featured on the news. 2 Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) INTRODUCTION: WEEKEND UPDATE Saturday Night Live is a sketch comedy show that debuted on NBC in 1975. -

1980 Brown and Gold Vol XII No 18 March 26, 1980

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Brown and Gold Archives and Special Collections 3-26-1980 1980 Brown and Gold Vol XII No 18 March 26, 1980 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "1980 Brown and Gold Vol XII No 18 March 26, 1980" (1980). Brown and Gold. 482. https://epublications.regis.edu/brownandgold/482 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brown and Gold by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. {' G.A. Meeting Tonight GOld) at 5:30 p.m. in the Lib.rary Regis College. Volume XII Wednesday, March 26, 1980 Number 18 New R.A. ,s Selected Dr. Ozog Honored As For Fall Faculty -Lecturer Of The Year lifestyles, and commitment to By Maureen Corbley residence hall living. by Gail Gassman The Office of Student Life has The A.A.'s main duties are to announced the selection of the Dr. Francis Ozog, of the act as Counselor by being chemistry department of Re new A.A.'s for the Fall 1980 avaliable to advise students semester. They are: Lisa Are gis, has been named Regis Col llano, Diane Coglan, Libby concerning personal problems; lege Faculty Lecturer of the Dale, Julie Griffin, Jim Haed coordinator by initiating year for 1980. Dr. Ozog has rich, Ed Haran, Shelly Hee, programs for the hall; Adminis been a part of the faculty for 30 Jane Hollman, Tom Kearney, trator by handling paperwork years and feels highly honored Mike Lingg, Chris McGrath, and attending meetings neces to have been given the award. -

“America's Most Famous Catholic” (According to Himself): Stephen

Brehm NARW 9.28.18 Hello NARWers, Thank you so much for reading the introduction and appendix/methodology section of my manuscript. Some background: I am transitioning my work from a dissertation into a book for Fordham University Press. The revised manuscript is due to the press January 31, 2019 (a timeline of events is attached). My reviewers main concern was that the introduction was too dissertation-y (not a surprise as it was a dissertation). So I have done my best to simplify the introduction, remove extraneous footnotes, and refocus sections. I have amped up (slightly) the Catholic component and toned down the humor & religion angle. I have reorganized the entire introduction and separated out the methodology section to an appendix. My questions for you: how is the new intro? Where can I punch it up and where is it confusing? I also have no idea how to start a book. What should the introductory sentences look like? Should I start with a story? What story? Should I begin with an introduction to Colbert himself or dive into my argument? Should I use another distinction between actor and character other than Colbert and COLBERT? More logistical questions: will the book suffer if I don’t have many photos? How should I go about obtaining rights to images I’ve screenshot? What should the cover be? I’m considering commissioning a friend to create a stained glass image of Colbert with ashes on his forehead in front of The Colbert Report stained glass. What covers have been evocative for you? Do you know other people I should be consulting about this? Thank you for your advice and guidance as I revise this manuscript. -

Equal Time” Rule (Equally) to Actors-Turned- Candidates

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 20 Volume XX Number 1 Volume XX Book 1 Article 3 2009 “I’m a Politician, But I Don’t Play One on TV”: Applying the “Equal Time” Rule (Equally) to Actors-Turned- Candidates Kimberlianne Podlas University of North Carolina at Greensboro, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Kimberlianne Podlas, “I’m a Politician, But I Don’t Play One on TV”: Applying the “Equal Time” Rule (Equally) to Actors-Turned- Candidates, 20 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 165 (2009). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol20/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I’m a Politician, But I Don’t Play One on TV”: Applying the “Equal Time” Rule (Equally) to Actors-Turned- Candidates Cover Page Footnote I’d like to thank the journal staff, and Regina Schaffer-Goldman, for improving the article and being great to work with. This article is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol20/iss1/3 C03_PODLAS_123009_FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 12/30/2009 11:12:47 AM “I’m a Politician, But I Don’t Play One on TV”: Applying the “Equal Time” Rule (Equally) to Actors-Turned- Candidates Kimberlianne Podlas INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ -

Montana Kaimin, April 25, 1980 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 4-25-1980 Montana Kaimin, April 25, 1980 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, April 25, 1980" (1980). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 7040. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/7040 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New festivities planned m on ta n a for this year’s Aber Day By STEVE VAN DYKE Library Staff Association. The UM Montana Kaimin Raportar bookstore will donate T-shirts to k a im in the.first 350 people who enter the The times when Aber Day meant Friday, April 25, 1980 Missoula, Mont VoL 82, No. 91 runs. drowning in a sea of beer and listening to rollicking bands such as Jimmy Buffett and Jerry Jeff Two runs Walker, are gone. Two runs are planned, a two- This year’s activities will be the mile race and a 6.2-mile race. The annual campus cleanup, two two-mile race is for the people who benefit runs for the Maureen and do not feel they can run a longer Mike Mansfield Library and an distance but would like to help the evening rock concert in the field library. -

A History of Television News Parody and Its Entry Into the Journalistic Field

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication Summer 8-13-2013 Nothing But the Truthiness: A History of Television News Parody and its Entry into the Journalistic Field Curt W. Hersey Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Recommended Citation Hersey, Curt W., "Nothing But the Truthiness: A History of Television News Parody and its Entry into the Journalistic Field." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/46 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTHING BUT THE TRUTHINESS: A HISTORY OF TELEVISION NEWS PARODY AND ITS ENTRY INTO THE JOURNALISTIC FIELD by CURT HERSEY Under the Direction of Ted Friedman ABSTRACT The relationship between humor and politics has been a frequently discussed issue for communication researchers in the new millennium. The rise and success of shows like The Daily Show and The Colbert Report force a reevaluation of the relationship between journalism and politics. Through archival research of scripts, programs, and surrounding discourses this dissertation looks to the past and historicizes news parody as a distinct genre on American television. Since the 1960s several programs on network and cable parodied mainstream newscasts and newsmakers. More recent eXamples of this genre circulate within the same discursive field as traditional television news, thereby functioning both as news in their own right and as a corrective to traditional journalism grounded in practices of objectivity. -

Tattler 12/16

Volume XXXI • Number 50 • December 16, 2005 WTAQ/Green Bay host Jerry Bader is calling for the resignation of local City Councilman Earl Van Den Heuvel after suspicions THE began to arise that the latter be the mystery face behind the AIN TREET mysterious voice of a controversial caller to Bader’s show who M S identified himself as Don. The call came on November 2nd, and Communicator Network featured this gem: “… Being a racist may be a smart thing to protect your property in this city. Until the people start changing, AA TT TT LL EE until the people start doing the things they need to do to bring TT RR around their people, you are not stupid for being a racist, you’re smart and you’re looking out for your property.” These volatile Publisher: Tom Kay Associate Publisher/Editor • Claire Sather comments led the station to bring the tapes of the show to a “No room for us at the Inn, either” forensic audiologist who matched the sound to Van Den Heuvel’s voice. Green Bay Mayor Jim Schmitt has joined Bader in asking Just Because The Conclave is Non-Profit Doesn’t Mean You for the councilman’s resignation. Van Den Heuvel vehemently Can’t Make Money! The Conclave’s Sales Director’s position denies any involvement in the call. for 2006 is now available (Brad Fuhr has exited to become an Account Exec for Air America/LA). This is a part-time, Congratulations to former Conclave Board member and Premiere commissioned sales position that requires strong communication Bob And Tom Show Dir/Affiliate Sales & Marketing Laura Gonzo skills, broad knowledge of the industry, and belief in the Conclave on her being honored by the Humane Society Of Louisiana and its educational mission.