Town Between Two Selves: Should Law Care More About Experiencing Selves Or Remembering Selves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAR : Winter 95

newest issue! home about nar our mission back issues Winter 1995 the staff submissions contacting us ● CyberCruft -- Ian Smith ● Women and Obstetrics: The Loss of Childbirth to Male Physicians -- Shira Kapplin ● Some scanned artwork -- Chris Sidi ● What the Information Superhighway Means to Me -- gavin guhxe ● Bureaucracy Watch ● The Lovely World of DisInformation -- gavin guhxe ● Digital Liberty -- Bill Frezza ● The Last Passenger -- Chad T. Carr Issues Currently On-Line ● Winter 1998 ● Summer 1997 ● Spring 1997 ● Spring 1996 ● Winter 1996 ● Fall 1995 ● Spring 1995 ● Winter 1995 ● Fall 1994 The North Avenue Review is a student publication of the Georgia Institute of Technology. It is published four times a year by our staff composed of people who write for us, submit art, help with layout, show up to meetings, etc. for the students of Georgia Tech. It has become a (relatively) long-standing tradition as an alternative form of expression. Mail suggestions about this page to Jimmy Lo at [email protected]. Mail questions or submissions to the North Avenue Review at [email protected]. North Avenue Review A Georgia Tech Publication. CyberCruft This is the Winter '95 installment of your guide to online nonsense, CyberCruft. Condom Country Good old-fashioned safe sex stuff. Hyperdiscordia May the goddess of discord be with you. Its a religion for the 90's. WaxMOO This is the hypermedia version of the film Wax Or The Discovery Of Television Among The Bees. Shred Of Dignity Skater's Union This guy is amazing. You should definately check out his info about his former house on Shipley street. -

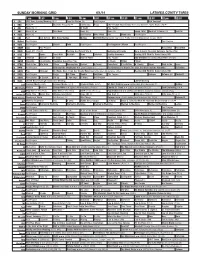

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

12 Hours Opens Under Blue Skies and Yellow Flags

C M Y K INSPIRING Instead of loading up on candy, fill your kids’ baskets EASTER with gifts that inspire creativity and learning B1 Devils knock off county EWS UN s rivals back to back A9 NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ Cammie Lester to headline benefit Plan for spray field for Champion for Children A5 at AP airport raises a bit of a stink A3 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 16, 2014 Health A PERFECT DAY Dept. in LP to FOR A RACE be open To offer services every other Friday starting March 28 BY PHIL ATTINGER Staff Writer SEBRING — After meet- ing with school and coun- ty elected officials Thurs- day, Florida Department of Health staff said the Lake Placid office at 106 N, Main Ave. will be reopen- ing, but with a reduced schedule. Tom Moran, depart- ment spokesman, said in a Katara Simmons/News-Sun press release that the Flor- The Mobil 1 62nd Annual 12 Hours of Sebring gets off to a flawless start Saturday morning at Sebring International Raceway. ida Department of Health in Highlands County is continuing services at the Lake Placid office ev- 12 Hours opens under blue ery other Friday starting March 28. “The Department con- skies and yellow flags tinues to work closely with local partners to ensure BY BARRY FOSTER Final results online at Gurney Bend area of the health services are avail- News-Sun Correspondent www.newssun.com 3.74-mile course. Emergen- able to the people of High- cy workers had a tough time lands County. -

Catholic N Ewspa Per in Continuous Publication Friday, January 21, 1983 Naming Latvian a Cardinal Called

O OD Inside storal d raft an alysis zpa l statem ents, U .S. draft show consistency, says archbishop o to reducing armaments. NNETH J. DOYLE special committee of U.S. bishops visit to Rome for meetings Jan. 18- statements indicates that on the CO H drafting the document. 19 with Vatican officials and two basic points of the American If anything, the papal thinking -c H •< draft there is a meeting of the seems in certain respects to lean > CO i CITY (NC) — “If anyone thinks that the draft delegations of several European esignate Joseph is off the papal mark, I would hierarchies to discuss the draft minds. toward greater restrictions invite the person to show us document. These two points are: regarding nuclear issues than the CD f Chicago expresses American draft. 3D his work when asked where,” says Archbishop The archbishop’s confidence is • Acceptance of the just war to > can thinks of the U .S. Bernardin when questioned about supported by the text of the draft theory coupled with the belief that The draft of the U.S. bishops fNJ X t pastoral on nuclear criticisms that the U.S. bishops' pastoral which shows a striking the theory virtually negates use of recognizes the validity of the just draft is incompatible with papal consistency with statements by nuclear weapons. war theory, even in today’s an input has been thinking. Pope John Paul II. • The acceptability of nuclear nuclear age. It describes that ositive and suppor- Archbishop Bernardin was A study of the d ra ft in deterrence but only coupled to theory and the moral choice of e man who heads the interviewed by NC News during a juxtaposition with papal strong bilateral efforts at (Continued on page 2) Pennsylvania's P riest dies largest weekly Fr. -

The Creative Life of 'Saturday Night Live' Which Season Was the Most Original? and Does It Matter?

THE PAGES A sampling of the obsessive pop-culture coverage you’ll find at vulture.com ost snl viewers have no doubt THE CREATIVE LIFE OF ‘SATURDAY experienced Repetitive-Sketch Syndrome—that uncanny feeling NIGHT LIVE’ WHICH Mthat you’re watching a character or setup you’ve seen a zillion times SEASON WAS THE MOST ORIGINAL? before. As each new season unfolds, the AND DOES IT MATTER? sense of déjà vu progresses from being by john sellers 73.9% most percentage of inspired (A) original sketches season! (D) 06 (B) (G) 62.0% (F) (E) (H) (C) 01 1980–81 55.8% SEASON OF: Rocket Report, Vicki the Valley 51.9% (I) Girl. ANALYSIS: Enter 12 51.3% new producer Jean Doumanian, exit every 08 Conehead, Nerd, and 16 1975–76 sign of humor. The least- 1986–87 SEASON OF: Samurai, repetitive season ever, it SEASON OF: Church Killer Bees. ANALYSIS: taught us that if the only Lady, The Liar. Groundbreaking? breakout recurring ANALYSIS: Michaels Absolutely. Hilarious? returned in season 11, 1990–91 character is an unfunny 1982–83 Quite often. But man-child named Paulie dumped Billy Crystal SEASON OF: Wayne’s SEASON OF: Mr. Robinson’s unbridled nostalgia for Herman, you’ve got and Martin Short, and Neighborhood, The World, Hans and Franz. SNL’s debut season— problems that can only rebuilt with SNL’s ANALYSIS: Even though Whiners. ANALYSIS: Using the second-least- be fixed by, well, more broadest ensemble yet. seasons 4 and 6 as this is one of the most repetitive ever—must 32.0% Eddie Murphy. -

Pritchett K.D

Pritchett k.d. lang Volume 4, Number 1, January 5, 1994 FREE PHOTO: JEFF HELBERG Why the -.;:. legislator as the "yuppie ninjas" - have passed Chozen-ji Zen through the dojo's gates temple and martial to "talk story" with artsdojo in upper Tanouye, including the governor, a number of Kalihi Valley just legislators, at least one might be one of the Bishop Estate trustee, developer Herbert most important Horita, big-gun lawyer places you've never Wally Fujiyama, banking CEO Uonel Tokioka and a heard of couple of men known widely as behind-the scenes "arrangers." A couple of notorious underworld figures have also been known to go to Chozen-ji, and even the FBl's curiosity has appar ently been stirred by rumors of the dojo's powerconnections. From one perspective, it looks like a conspiracy theorist's dream. But f there's one thing this press. Chozen-ji is a Zen talk to a dojo follower town has a reputation Buddhist temple and and you'll get quite a dif.. Iforbesides mai tais somewhat exclusive cen ferent picture, one of an and hula girls, it's secre ter for the martial, fine angel network of tive power cliques that and healing arts headed dedicated people, as cut back-room deals far by locally born archbishop well intentioned as they from the public eye. The Tanouye Tenshin Roshi are connected, nurturing kinds of "hot spots" (roshiisan hope with the Story by where the influential con honorific title DEREK FERRAR guidance of gregate are many: the used for Tanouye. From golflinks, the Pacific heads of Zen temples), this perspective, the Club, reunions of the who teaches the samurai activities of the roshi 442nd Regiment, Vegas. -

Cinematic Specific Voice Over

CINEMATIC SPECIFIC PROMOS AT THE MOVIES BATES MOTEL BTS A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS CHOZEN S1 --- IN THEATER "TURN OFF CELL PHONE" MESSAGE FX NETWORKS E!: BELL MEDIA WHISTLER FILM FESTIVAL TRAILER BELL MEDIA AGENCY FALLING SKIES --- CLEAR GAZE TEASE TNT HOUSE OF LIES: HANDSHAKE :30 SHOWTIME VOICE OVER BEST VOICE OVER PERFORMANCE ALEXANDER SALAMAT FOR "GENERATIONS" & "BURNOUT" ESPN ANIMANIACS LAUNCH THE HUB NETWORK JUNE STUNT SPOT SHOWTIME LEADERSHIP CNN NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL SUMMER IMAGE "LIFE" SHAW MEDIA INC. Page 1 of 68 TELEVISION --- VIDEO PRESENTATION: CHANNEL PROMOTION GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT GENERIC :45 RED CARPET IMAGE FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY HAPPY DAYS FOX SPORTS MARKETING HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA MUCH: TMC --- SERENA RYDER BELL MEDIA AGENCY SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN COMPETITIVE CAMPAIGN DIRECTV DISCOVERY BRAND ANTHEM DISCOVERY, RADLEY, BIGSMACK FOX SPORTS 1 LAUNCH CAMPAIGN FOX SPORTS MARKETING LAUNCH CAMPAIGN PIVOT THE HUB NETWORK'S SUMMER CAMPAIGN THE HUB NETWORK ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT BRAG PHOTOBOOTH CBS TELEVISION NETWORK BRAND SPOT A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS Page 2 of 68 NBC 2013 SEASON NBCUNIVERSAL SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO ZTÉLÉ – HOSTS BELL MEDIA INC. ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN NICKELODEON HALLOWEEN IDS 2013 NICKELODEON HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA NICKELODEON KNIT HOLIDAY IDS 2013 NICKELODEON SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND CAMPAIGN BRAVO NICKELODEON SUMMER IDS 2013 NICKELODEON GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT --- LONG FORMAT "WE ARE IT" NUVOTV AN AMERICAN COACH IN LONDON NBC SPORTS AGENCY GENERIC: FBC COALITION SIZZLE (1:49) FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY PBS UPFRONT SIZZLE REEL PBS Page 3 of 68 WHAT THE FOX! FOX BROADCASTING CO. -

Permission Granted for Weddings at Church of Our Lady of Loretto

Ax murders - page 3 Enthusiastic students check out lower prices at new store s opening By MARK S. PANKOWSKI tive to the bookstore,” said New s S ta ff Cavanaugh senior Joe Pangilinan. “ I see these notebooks here The N otre Dame Student Saver cheaper than they were in the the Store opened its doors yesterday to bookstore,” said John Gardiner, a an enthusiastic crow d o f students on Stanford sophomore. “It’s good to the second floor of LaFortune Stu see that the Student G overnm ent is dent Center. offering a viable service for the stu Comments about the new store dents.” ranged from “ it’s a good idea ” to “ it ’s Most of the negative comments the greatest supersaver ever as made were complaints about the sembled by a human being.” lack of college-ruled notebooks and The student store manager, Rick health and beauty items. Schimpf Schimpf, was very happy with the hopes to remedy those problems in response of the student body. the com ing days. “ We had 15 to 20 people standing "I’m working with our distributor outside before we even opened, ” to make sure the health and beauty said Schimpf. “We made $450 the aids w ill be in tomorrow (Jan. 18) - first hour,” he said, adding, Monday at the latest. ” “ Business is fantastic.” Regarding the college ruled Most people who came into the notebooks, Schimpf said, “In the Student Saver were there for one report given by the committee, they reason: to save money. see "This is definitely a better alterna STORE, page 6 Ethiopia blocked aid, U.S. -

Farley Resume 2013

William N. Farley EDUCATION 1971 M.F.A. California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California. major: Sculpture; minor: Filmmaking. 1969 B.F.A. Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, Maryland. major: Sculpture. 1968 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine. 1961-64 Vesper George School of Art, Boston, Massachusetts. PHOTOGRAPHY EXHIBITIONS 2013 SFMoMA Artist Gallery, Fort Mason, CA 2011 Outlandish, Contemporary Depictions of Nature, Bedford Gallery, Walnut Creek, CA 2011 LandsCApes: Glimpses of Everyday California, de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara, CA FILM EXHIBITIONS Shadow & Light, The Life and Art of Elaine Badgley Arnoux 2009 Ventura Film Festival, Ventura, California. 2009 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2009 Mill Valley Film Festival, Mill Valley, California. 2009 Santa Fe Film Festival, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Walt Whitman’s Song Of Myself 2008 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2008 FIAAP 08 Festival Internacional Audiovisual de Artes Performativas Museu Nacional do Teatro Lisboa, Portugal. Darryl Henriques Is In Show Business 2007 Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, California. 2006 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2006 Mill Valley Film Festival, Mill Valley, California. Arianna’s Journey 2007 Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, California. The Stories 2007 Mendocino Film Festival, Mendocino, California. 2007 Rhode Island International Film Festival, Providence, Rhode Island. 2007 Cleveland Cinematheque, Cleveland, Ohio. 2006 Mill Valley Film Festival, Mill Valley, California. 2006 Southern Exposure Mayhem Film Festival, San Francisco, California. The Old Spaghetti Factory 2009 Cinema By The Bay, San Francisco International Film Festival, San Francisco, California. 2001 PBS national broadcast, 90 cities in the U.S. -

The Artillery of Critique Versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing up to Propaganda, 1990-1999

THE ARTILLERY OF CRITIQUE VERSUS THE GENERAL UNCRITICAL CONSENSUS: STANDING UP TO PROPAGANDA, 1990-1999 by Andrew Alexander Monti Master of Arts, York University, Toronto, Canada, 2013 Bachelor of Science, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy, 2005 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Joint Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2018 © Andrew Alexander Monti, 2018 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The Artillery of Critique versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing Up to Propaganda, 1990-1999 Andrew Alexander Monti Doctor of Philosophy Communication and Culture Ryerson University, 2018 In 2011, leading comedy scholars singled-out two shortcomings in stand-up comedy research. The first shortcoming suggests a theoretical void: that although “a number of different disciplines take comedy as their subject matter, the opportunities afforded to the inter-disciplinary study of comedy are rarely, if ever, capitalized on.”1 The second indicates a methodological void: there is a “lack of literature on ‘how’ to analyse stand-up comedy.”2 This research project examines the relationship between political consciousness and satirical humour in stand-up comedy and attempts to redress these two shortcomings. -

The Mindfulness Sampler

The Mindfulness Sampler Shambhala Authors on the Power of Awareness in Daily Life Mindfulness Sampler fourth pass 2-3-14.indd 1 2/3/14 11:54 AM This page intentionally left blank. THE MINDFULNESS SAMPLER f Shambhala Authors on the Power of Awareness in Daily Life shambhala Boston & London 2014 Mindfulness Sampler fourth pass 2-3-14.indd 1 2/3/14 11:54 AM Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2014 by Shambhala Publications, Inc. Cover photograph: Apples in Bushel © Kevin Thomas and Andrea Pluhar All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. eisbn 978-0-8348-2961-9 eisbn 978-0-8348-2981-7 (Shambhala.com edition) Mindfulness Sampler 2-4-14.indd 2 2/4/14 2:53 PM CONTENTS f Introduction v Happiness and Peace Are Possible 1 Thich Nhat Hanh The Liberating Practice of Mindfulness 19 Jack Kornfield Not Causing Harm 33 Pema Chödrön The Practice of Ordinary Life 41 Jan Chozen Bays, MD The Four Foundations of Mindfulness 61 Chögyam Trungpa Mindfulness in Relationships 101 David Richo Work’s Invitation to Wake Up 119 Michael Carroll Mindfulness Sampler fourth pass 2-3-14.indd 3 2/3/14 11:54 AM iv C Contents Raising Mindful Kids 133 Eline Snel Mindfulness and Addiction 145 Lawrence A. Peltz, MD Mindful Communication 171 Susan Gillis Chapman Further Readings 197 Mindfulness Sampler fourth pass 2-3-14.indd 4 2/3/14 11:54 AM INTRODUCTION f “Life is accessible only in the present moment.” This revo- lutionary teaching of the Buddha, as emphasized by the great Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, is the hallmark of the mindful- ness movement—and it is taking the world by storm. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/1/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/1/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Press 2014 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Exped. Wild World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: FedEx 400 Benefiting Autism Speaks. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program The Forgotten Children Paid Program 22 KWHY Iggy Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Heart 411 (TVG) Å Painting the Wyland Way 2: Gathering of Friends Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions For You (TVG) 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) El Chavo Fútbol Fútbol 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Walk in the Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee.