The Mindfulness Sampler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005

Volume 23 • Number 2 • Fall 2005 Primary Point Primary Point 99 Pound Road, Cumberland RI 02864-2726 U.S.A. Telephone 401/658-1476 • Fax 401/658-1188 www.kwanumzen.org • [email protected] online archives www.kwanumzen.org/primarypoint Published by the Kwan Um School of Zen, a nonprofit religious corporation. The founder, Zen Master Seung Sahn, 78th Patriarch in the Korean Chogye order, was the first Korean Zen Master to live and teach in the West. In 1972, after teaching in Korea and Japan for many years, he founded the Kwan Um sangha, which today has affiliated groups around the world. He gave transmission to Zen Masters, and “inka”—teaching authority—to senior students called Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, “dharma masters.” The Kwan Um School of Zen supports the worldwide teaching schedule of the Zen Masters and Ji Do Poep Sa Nims, assists the member Zen centers and groups in their growth, issues publications In this issue on contemporary Zen practice, and supports dialogue among religions. If you would like to become a member of the School and receive Let’s Spread the Dharma Together Primary Point, see page 29. The circulation is 5000 copies. Seong Dam Sunim ............................................................3 The views expressed in Primary Point are not necessarily those of this journal or the Kwan Um School of Zen. Transmission Ceremony for Zen Master Bon Yo ..............5 © 2005 Kwan Um School of Zen Founding Teacher In Memory of Zen Master Seung Sahn Zen Master Seung Sahn No Birthday, No Deathday. Beep. Beep. School Zen Master Zen -

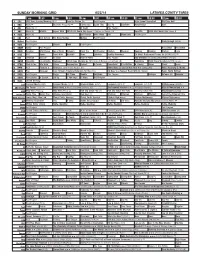

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

12 Hours Opens Under Blue Skies and Yellow Flags

C M Y K INSPIRING Instead of loading up on candy, fill your kids’ baskets EASTER with gifts that inspire creativity and learning B1 Devils knock off county EWS UN s rivals back to back A9 NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ Cammie Lester to headline benefit Plan for spray field for Champion for Children A5 at AP airport raises a bit of a stink A3 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 16, 2014 Health A PERFECT DAY Dept. in LP to FOR A RACE be open To offer services every other Friday starting March 28 BY PHIL ATTINGER Staff Writer SEBRING — After meet- ing with school and coun- ty elected officials Thurs- day, Florida Department of Health staff said the Lake Placid office at 106 N, Main Ave. will be reopen- ing, but with a reduced schedule. Tom Moran, depart- ment spokesman, said in a Katara Simmons/News-Sun press release that the Flor- The Mobil 1 62nd Annual 12 Hours of Sebring gets off to a flawless start Saturday morning at Sebring International Raceway. ida Department of Health in Highlands County is continuing services at the Lake Placid office ev- 12 Hours opens under blue ery other Friday starting March 28. “The Department con- skies and yellow flags tinues to work closely with local partners to ensure BY BARRY FOSTER Final results online at Gurney Bend area of the health services are avail- News-Sun Correspondent www.newssun.com 3.74-mile course. Emergen- able to the people of High- cy workers had a tough time lands County. -

Pritchett K.D

Pritchett k.d. lang Volume 4, Number 1, January 5, 1994 FREE PHOTO: JEFF HELBERG Why the -.;:. legislator as the "yuppie ninjas" - have passed Chozen-ji Zen through the dojo's gates temple and martial to "talk story" with artsdojo in upper Tanouye, including the governor, a number of Kalihi Valley just legislators, at least one might be one of the Bishop Estate trustee, developer Herbert most important Horita, big-gun lawyer places you've never Wally Fujiyama, banking CEO Uonel Tokioka and a heard of couple of men known widely as behind-the scenes "arrangers." A couple of notorious underworld figures have also been known to go to Chozen-ji, and even the FBl's curiosity has appar ently been stirred by rumors of the dojo's powerconnections. From one perspective, it looks like a conspiracy theorist's dream. But f there's one thing this press. Chozen-ji is a Zen talk to a dojo follower town has a reputation Buddhist temple and and you'll get quite a dif.. Iforbesides mai tais somewhat exclusive cen ferent picture, one of an and hula girls, it's secre ter for the martial, fine angel network of tive power cliques that and healing arts headed dedicated people, as cut back-room deals far by locally born archbishop well intentioned as they from the public eye. The Tanouye Tenshin Roshi are connected, nurturing kinds of "hot spots" (roshiisan hope with the Story by where the influential con honorific title DEREK FERRAR guidance of gregate are many: the used for Tanouye. From golflinks, the Pacific heads of Zen temples), this perspective, the Club, reunions of the who teaches the samurai activities of the roshi 442nd Regiment, Vegas. -

Cinematic Specific Voice Over

CINEMATIC SPECIFIC PROMOS AT THE MOVIES BATES MOTEL BTS A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS CHOZEN S1 --- IN THEATER "TURN OFF CELL PHONE" MESSAGE FX NETWORKS E!: BELL MEDIA WHISTLER FILM FESTIVAL TRAILER BELL MEDIA AGENCY FALLING SKIES --- CLEAR GAZE TEASE TNT HOUSE OF LIES: HANDSHAKE :30 SHOWTIME VOICE OVER BEST VOICE OVER PERFORMANCE ALEXANDER SALAMAT FOR "GENERATIONS" & "BURNOUT" ESPN ANIMANIACS LAUNCH THE HUB NETWORK JUNE STUNT SPOT SHOWTIME LEADERSHIP CNN NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL SUMMER IMAGE "LIFE" SHAW MEDIA INC. Page 1 of 68 TELEVISION --- VIDEO PRESENTATION: CHANNEL PROMOTION GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT GENERIC :45 RED CARPET IMAGE FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY HAPPY DAYS FOX SPORTS MARKETING HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA MUCH: TMC --- SERENA RYDER BELL MEDIA AGENCY SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN COMPETITIVE CAMPAIGN DIRECTV DISCOVERY BRAND ANTHEM DISCOVERY, RADLEY, BIGSMACK FOX SPORTS 1 LAUNCH CAMPAIGN FOX SPORTS MARKETING LAUNCH CAMPAIGN PIVOT THE HUB NETWORK'S SUMMER CAMPAIGN THE HUB NETWORK ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT BRAG PHOTOBOOTH CBS TELEVISION NETWORK BRAND SPOT A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS Page 2 of 68 NBC 2013 SEASON NBCUNIVERSAL SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO ZTÉLÉ – HOSTS BELL MEDIA INC. ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN NICKELODEON HALLOWEEN IDS 2013 NICKELODEON HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA NICKELODEON KNIT HOLIDAY IDS 2013 NICKELODEON SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND CAMPAIGN BRAVO NICKELODEON SUMMER IDS 2013 NICKELODEON GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT --- LONG FORMAT "WE ARE IT" NUVOTV AN AMERICAN COACH IN LONDON NBC SPORTS AGENCY GENERIC: FBC COALITION SIZZLE (1:49) FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY PBS UPFRONT SIZZLE REEL PBS Page 3 of 68 WHAT THE FOX! FOX BROADCASTING CO. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 15 Fall 2013 SPECIAL SECTION: Graduate Student Symposium TITLE iii What’s Buddhism Got to Do With It? Popular and Scientific Perspectives on Mindful Eating Chenxing Han Institute of Buddhist Studies In 2010, American talk show host Oprah Winfrey interviewed the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh about Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Living, a book he co-authored with nutritionist Lilian Cheung. Oprah asked the Vietnamese Zen master for “his take on the root of our weight problems” and advice on “how to change [our] own eating habits forever.”1 Savor joined a rapidly expanding repertoire of popu- lar books touting the benefits of mindful eating.2 The book promised to “end our struggles with weight loss once and for all” while distin- guishing itself from the diet fads of the $50-billion-a-year weight loss industry.3 Complementing the popular literature on mindful eating, an increasing number of scientific studies offer empirical, qualitative, and clinical perspectives on the efficacy of mindfulness interventions for obesity and eating disorders.4 A 2011 article characterizes mindful eating as “a growing trend designed to address both the rising rates of obesity and the well-docu- mented fact that most diets don’t work.”5 Unlike Savor, the article does not contain a single mention of Buddhism. An examination of more than two dozen articles in the scientific literature on mindfulness- based interventions for obesity and eating disorders yields a similar dearth of references to Buddhism. Popular books on mindful eating mention Buddhism more frequently, but often in superficial or im- precise ways that romanticize and essentialize more than they edify. -

Zen River Cookbook

ZEN RIVER COOKBOOK MOUTH-WATERING VEGETARIAN RECIPES BY TAMARA MYOHO GABRYSCH These delicious recipes have been created, tested, and compiled by a Zen cook with decades of experience. The colour photos are beautiful and make you want to head for the kitchen and start chopping. It is rare to find a book that helps you cook healthy, tasty food for large groups. An unexpected treat is the discovery that the recipes are interwoven with inspiring Zen teachings. – Jan Chozen Bays, MD, is a Zen master in the White Plum lineage of the late master Taizan Maezumi Roshi. Her many books include Mindful Eating: Free Yourself from Overeating and Other Unhealthy Relationships with Food (Shambhala 2009) The Zen River Cookbook is the work of a Zen Master. It is filled with flavourful recipes, thoughtful instruction, and beautiful images. This book captures the simplicity and dynamic range of a true Zen kitchen with variety, clarity, and nourishment for the body, mind, and spirit. – Diane Musho Hamilton is an award-winning professional mediator, author, facilitator, and teacher of Zen at Two Arrows Zen and Integral Spirituality. Diane is the author of Everything is Workable: A Zen Approach to Conflict Resolution, (Shambhala, 2013). She is also featured in The Hidden Lamp: Stories from Twenty-Five Centuries of Awakened Women (Wisdom, 2014). The Zen River Cookbook is a wonderful collection of practical, accessible, creative, and delicious recipes. They lend themselves to the preparation of simple or substantial meals for the family, for a dinner party, or for a large function. This is good food – that it is vegetarian is not an issue. -

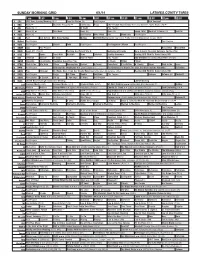

Sunday Morning Grid 6/1/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/1/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Press 2014 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Exped. Wild World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: FedEx 400 Benefiting Autism Speaks. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program The Forgotten Children Paid Program 22 KWHY Iggy Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Heart 411 (TVG) Å Painting the Wyland Way 2: Gathering of Friends Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions For You (TVG) 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) El Chavo Fútbol Fútbol 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Walk in the Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Cherry Blossom Fete Dons Trade Emphasis Bed, Beaten and Abused

YOUNGER NISEI, SANSEI LAUNCH Per PIONEER PROJECT FOR ISSEI AGED spec LOS ANGELES - Pioneer A 8roup oC 32 hs.i, .ccom Project, a. lh. name sugge.t., panled by Pioneer Project I. an o.. ~al1i ..tion devoted to tnt-mbers, cmbnrkcd on n doy open It'll Une. of eommuniea long .xcltt.lon to the Port 'or lives Uon with 1... 1 elUo.ns h ...c. Los AnJ(~lcs on Nov. ::1O. Since its (ormation 1ut TI'nnspoI,tnllon And lunch :rur, the younr ,roup with welC provided by the City 1\.-,. JERRY ENOMOTO ...IIt-nc. of J.ffrey M.~ Rnd II,. day's activilles W.I ' ~ NaUofill JACL Pruldent au1 of lb. JAOL offl•• , haa highlii{bted by n boat ride VOL. 68 NO.9 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 1969 IUQteutull:r IPousored IfIV around thc hArbOl' Rn d sight. Edit-Bus, Office', ow A '"6986 TEN ............. Sacramento f"ral pro.ratna and events scelng nt the Port. oC Call. IUA .,.. ",.n40 In A (~W w(,eks the Exreu for th. enjoyment 01 1... 1 PtoJc~t ~:::::;~~~~~iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiijii iiiiiiiiliiiii ~~~iBii;;ii;;;;;:;;;;;;;;~;:;:;;~;;::::::~---------- ti,'e ommillce, which might ..sld. nla. their Neowmc Year'smben ,AveEve upto __________ -.J '~ mochl " be called Ihe "sleering eom "As the pionr:ers or our ml1ke In l)ropQ.rB communit,.)', the Issei hove ex Uon for A. rain New YeRr', n,it\"." ot the NationRi JA 1)(13' rc t~to Ke th or nod "0100- SEA nLE rCL ASKS CL, \\ III cQnvcne tor its scc periences, kllowlc:'!dltc and talents 10 imparl to all oC us. -

SYNOPSIS: Originally in Booklet Form, Information Presented Here Is with the Intention of Providing Clear Information About a Teacher of Teachers

SYNOPSIS: Originally in booklet form, information presented here is with the intention of providing clear information about a teacher of teachers. All time references are as originally published, circa 1988. The Great Stupa of Dharmakaya Which Liberates Upon Seeing and information regarding the work and life of Vidyadhara the Venerable Trungpa, Rinpoche is included here. For more information, write or call: Rocky Mountain Shambhala Center, 4921 County Rd 68C, Red Feather Lakes, CO 80545 Voice: (970) 881 2184; Telecopier: 970 881 2909 Contents SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUPA Page 3 SYMBOLISM OF THE STUPA Page 4 THE GREAT STUPA OF DHARMAKAYA Page 5 YOUR PARTICIPATION Page 7 VIDYADHARA, THE VENERABLE CH™GYAM TRUNGPA, RINPOCHE Page 9 ORGANIZATIONS FOUNDED (Selected List) Page 11 BOOKS PUBLISHED Page 13 >>>> VIDYADHARA THE VENERABLE CH™GYAM TRUNGPA, RINPOCHE (photo caption: The Vidyadhara taught in America for seventeen years. He brought to us the precious living heritage of the tradition of Buddhism and the teachings of Shambhala.) His Life and Teachings Vidyadhara the Venerable Ch”gyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, achieved international repute as a Buddhist leader and teacher whose vitality in bringing Buddhist and Tibetan traditions to the Western world attracted thousands of students. He was the first spiritual master to translate extensively the profound Tibetan Buddhist and Shambhala teachings into English. Because of his extraordinary command of English and his understanding of Western culture, he was able to impart these teachings firsthand to his students and to develop within them a heartfelt connection to the practice of meditation. In his numerous books and through the seminars and programs he conducted, he embodied the living quality, richness, and scope of the Buddhist tradition of Tibet.