Nicholas Quennell Oral History Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera

How To Quote This Material ©Jack Fritscher www.JackFritscher.com Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera — Take 2: Pentimento for Robert Mapplethorpe Manuscript TAKE 2 © JackFritscher.com PENTIMENTO FOR ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE FETISHES, FACES, AND FLOWERS Of EVIL1 “He wanted to see the devil in us all... The man who liberated S&M Leather into international glamor... The man Jesse Helms hates... The man whose epic movie-biography only Ken Russell could re-create...” Photographer Mapplethorpe: The Whitney, the NEA and censorship, Schwarzenegger, Richard Gere, Susan Sarandon, Paloma Picasso, Hockney, Warhol, Patti Smith, Scavullo, sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, S&M, flowers, black leather, fists, Allen Ginsberg, and, once-upon-a-time, me... The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently a dozen years ago. The High Time was in full upswing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here. In 1977, Robert Mapplethorpe arrived unexpectedly in my life. I was editor of the San Francisco—based international leather magazine, Drummer, and Robert was a New York shock-and-fetish photographer on the way up. Drummer wanted good photos. Robert, already infamous for his leather S&M portraits, always seeking new models with outrageous trips, wanted more specific exposure within the leather community. Our mutual, professional want ignited almost instantly into mutual, personal passion. -

C100 Trip to Houston

Presented in partnership with: Trip Participants Doris and Alan Burgess Tad Freese and Brook Hartzell Bruce and Cheryl Kiddoo Wanda Kownacki Ann Marie Mix Evelyn Neely Yvonne and Mike Nevens Alyce and Mike Parsons Your Hosts San Jose Museum of Art: S. Sayre Batton, deputy director for curatorial affairs Susan Krane, Oshman Executive Director Kristin Bertrand, major gifts officer Art Horizons International: Leo Costello, art historian Lisa Hahn, president Hotel St. Regis Houston Hotel 1919 Briar Oaks Lane Houston, Texas, 77027 Phone: 713.840.7600 Houston Weather Forecast (as of 10.31.16) Wednesday, 11/2 Isolated Thunderstorms 85˚ high/72˚ low, 30% chance of rain, 71% humidity Thursday, 11/3 Partly Cloudy 86˚ high/69˚ low, 20% chance of rain, 70% humidity Friday, 11/4 Mostly Sunny 84˚ high/63 ˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 60% humidity Saturday, 11/5 Mostly Sunny 81˚ high/61˚ low, 0% chance of rain, 42% humidity Sunday, 11/6 Partly Cloudy 80˚ high/65˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 52% humidity Day One: Wednesday, November 2, 2016 Dress: Casual Independent arrival into George Bush Intercontinental/Houston Airport. Here in “Bayou City,” as the city is known, Houstonians take their art very seriously. The city boasts a large and exciting collection of public art that includes works by Alexander Calder, Jean Dubuffet, Michael Heizer, Joan Miró, Henry Moore, Louise Nevelson, Barnett Newman, Claes Oldenburg, Albert Paley, and Tony Rosenthal. Airport to hotel transportation: The St. Regis Houston Hotel offers a contracted town car service for airport pickup for $120 that would be billed directly to your hotel room. -

Arnold) Glimcher, 2010 Jan

Oral history interview with Arne (Arnold) Glimcher, 2010 Jan. 6-25 Funding for this interview was provided by the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Arne Glimcher on 2010 January 6- 25. The interview took place at PaceWildenstein in New York, NY, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Arne Glimcher has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES McELHINNEY: This is James McElhinney speaking with Arne Glimcher on Wednesday, January the sixth, at Pace Wildenstein Gallery on— ARNOLD GLIMCHER: 32 East 57th Street. MR. McELHINNEY: 32 East 57th Street in New York City. Hello. MR. GLIMCHER: Hi. MR. McELHINNEY: One of the questions I like to open with is to ask what is your recollection of the first time you were in the presence of a work of art? MR. GLIMCHER: Can't recall it because I grew up with some art on the walls. So my mother had some things, some etchings, Picasso and Chagall. So I don't know. -

October 30 – December 30, 2021

ST 71 OCTOBER 30 – DECEMBER 30, 2021 EXHIBITION 71st A•ONE – A•ONE is a national competition/exhibition highlighting the diversity of work that is currently being made by established and emerging artists. Eligibility – Open to all artists, 18 years of age and older, residing in the United States. Original artwork in any media will be considered. Giclée reproductions of original works will not be accepted. Eligible artwork must have been completed after January 1, 2019, and fall within the restrictions. Awards – Grand Prize, awards an artist a solo exhibition at Silvermine Arts Center with a $1,000 stipend for show related expenses. The Juror has additional awards to give at their discretion. Entry Fee – $50 for up to 5 entries. To be considered for the Grand Prize Award, artists are required to enter a minimum of three works. Online entry – Complete the 71st A•ONE entry form on Slideroom – https://silvermineart.slideroom.com JUROR Richard Klein is a curator, artist, and writer. Since 1999 he has been Exhibitions Director of The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut. In his two decade long career as a curator of contemporary art he has organized over 80 exhibitions, including solo shows of the work of Janine Antoni, Sol LeWitt, Mark Dion, Roy Lichtenstein, Hank Willis Thomas, Brad Kahlhamer, Kim Jones, Jack Whitten, Jessica Stockholder, Tom Sachs, and Elana Herzog. Major curatorial projects at The Aldrich have included Fred Wilson: Black Like Me (2006), No Reservations: Native American History and Culture in Contemporary Art (2006), Elizabeth Peyton: Portrait of an Artist (2008), Shimon Attie: MetroPAL.IS. -

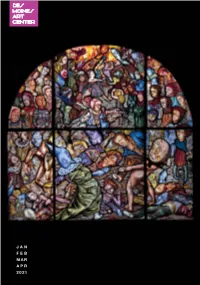

Jan Feb Mar Apr 2021 from the Director

FROM THE DIRECTOR JAN FEB MAR APR 2021 FROM THE DIRECTOR Submit your story I am sure you would agree, let us put 2020 behind us and anticipate a better year in 2021. With this expectation in mind, your Art Center teams are moving ahead with major plans for the new year. Our exhibitions We continue to include The Path to Paradise: Judith Schaechter’s accept personal Stained-Glass Art; Justin Favela: Central American; stories in response and Louis Fratino: Tenderness revealed along with to Black Stories. Iowa Artists 2021: Olivia Valentine. An array of print gallery and permanent collections projects, including Enjoy this story an exhibition that showcases our newly conserved submission from painting by Francisco Goya, Don Manuel Garcia de Candace Williams. la Prada, 1811, and another that features our works by Claes Oldenburg, will augment and complement Seen. I felt seen as I walked these projects. The exhibitions will continue to through the Black Stories address our goals of being an inclusive and exhibition with my friend. welcoming institution, while adding to the scholarship As history and experiences of the field, engaging our local communities in were shared through art, meaningful ways, and providing a site for the I remembered my mom community to gather together, at least virtually taking my sister and I to (for now), to share ideas and perspectives. the California African- Our Black Stories project has done just this American Museum often. as we continue to receive personal stories from She would buy children’s the community for possible inclusion in a books written by Black publication. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

A Finding Aid to the Oliver Ingraham Lay, Charles Downing Lay, and Lay Family Papers, 1789-2000, Bulk 1870-1996, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Oliver Ingraham Lay, Charles Downing Lay, and Lay Family papers, 1789-2000, bulk 1870-1996, in the Archives of American Art Joy Weiner Glass plate negatives in this collection were digitized in 2019 with funding provided by the Smithsonian Women's Committee. 2006 April Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Oliver Ingraham Lay and Marian Wait Lay Papers, 1789-1955................ 5 Series 2: Charles Downing Lay and Laura Gill Lay Papers, 1864-1993................ 11 Series 3: Fidelia Bridges Papers, -

41-Story Mixed-Use Academic and Condominium Building in Manhattan, New York in the United States Overview of the 100 Claremont Avenue Project

July 15, 2020 Press Release Keiichi Yoshii, President, CEO and COO Daiwa House Industry Co., Ltd. 3-3-5 Umeda, Kita-ku, Osaka 41-story Mixed-Use Academic and Condominium Building in Manhattan, New York in the United States Overview of the 100 Claremont Avenue Project Daiwa House Industry Co., Ltd. (Head Office: Osaka, President, CEO and COO: Keiichi Yoshii; hereinafter “Daiwa House”) is pleased to announce that we have determined the overview of our 100 Claremont Avenue Project. This is a project for a 41-story mixed-use academic and condominium building that we are working on in Manhattan, New York in the United States of America (hereinafter “the U.S.”) 【 Image of the 100 Claremont Avenue Project (high-rise on right)】 We will carry out this project through our U.S. subsidiary Daiwa House Texas Inc. This is a project that we will work on together with Lendlease Americas Inc. – the U.S. subsidiary of Lendlease Corporation Limited that is headquartered in Sydney in Australia and involved in projects worldwide, and New York City based developer, L+M Development Partners. The 100 Claremont Avenue Project is a project we will develop on the campus of Union Theological Seminary. This is located in a neighborhood lined with educational and cultural facilities in Morningside Heights in Manhattan, New York. The project will become the tallest high-rise building in Morningside Heights. It will be a 41-story high-rise building with a total floor area of 32,888 m2 (354,000sqft) that is comprised of 165 units for sale, and the educational facilities and faculty housing of Union Theological Seminary. -

The Report Card

New Yorkers for Parks The Urban Center 457 Madison Avenue New Yorkers for Parks (NY4P) is a coalition of civic, greening, New York, NY 10022 212.838.9410 recreation, and economic development organizations that advocates www.ny4p.org for a higher level of park services in every community. In addition to The Report Card on Parks, Parks Advocacy Day NY4P: NY4P also produces numerous research Rallies New Yorkers at City Hall once a Works tirelessly to promote and protect projects and community outreach events. year to meet with Council Members to the city’s 28,700 acres of parkland and All of these are designed to keep parks advocate for a citywide parks legislative 1,700 public park properties; and open spaces on the public agenda agenda and local neighborhood concerns. and to provide park users with tools that Raises awareness about the importance The Community Design Program help them to advocate for improved of parks as a vital public service essential Provides pro bono design services to park services. to strengthening the City and its residents; organizations in underserved communities Report Card on Parks to improve and beautify local parks. Serves as an independent watchdog The Report Card on Parks is the first publicly that conducts research and works toward The Natural Areas Initiative accessible park-by-park evaluation of creating a more equitable and efficient A joint program of NY4P and New NYC’s neighborhood parks. parks and recreational system; York City Audubon that promotes the City Council District Profiles protection and effective management Activates public discussion regarding best “One stop shopping” for maps, photo- of New York City’s natural areas. -

SHELTON HOTEL, 525 Lexington Avenue

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 22, 2016, Designation List 490 LP-2557 SHELTON HOTEL, 525 Lexington Avenue (aka 523-527 Lexington Avenue, 137-139 East 48th Street, 136-140 East 49th Street), Manhattan Built: 1922-23; architect, Arthur Loomis Harmon Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan, Tax Map Block 1303, Lot 53 On July 19, 2016 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Shelton Hotel and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 4). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of the law. A representative of the owner spoke in favor of the designation acknowledging the building’s architectural and cultural importance. There were five other speakers in support of the designation including representatives of Borough President Gale Brewer, Community Board 6, the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Historic Districts Council, and the Municipal Arts Society. A representative of the Real Estate Board of New York spoke in opposition to the designation. A representative of Council Member Daniel Garodnick submitted written testimony in support of the designation. Two other individuals have also submitted emails in support of the designation. Summary Designed by architect Arthur Loomis Harmon and completed in 1923, the Shelton Hotel was one of the first “skyscraper” residential hotels. With its powerful massing it played an important role in the development of the skyscraper in New York City. Located on the east side of Lexington Avenue between 48th and 49th Streets, it is one of the premiere hotels constructed along the noted “hotel alley” stretch of Lexington Avenue, which was built as part of the redevelopment of this section of East Midtown that followed the opening of Grand Central Terminal and the Lexington Avenue subway line. -

Botanic Garden News

Spring 2010 Page 1 Botanic Garden News The Botanic Garden Volume 13, No. 1 of Smith College Spring 2010 Floral Radiography Madelaine Zadik E veryone loves flowers, but imagine how they would appear if you had x -ray vision. Our latest exhibition, The Inner Beauty of Flowers, presents just that. Once radiologist Merrill C. Raikes retired, he turned his x-rays away from diagnostic medicine and instead focused them on flowers. The resulting floral radiographs bring to light the inner structure of flowers that normally remains invisible to us. It wasn’t easy for Dr. Raikes to figure out the exact techniques that would produce the desired results, but he finally discovered how to get the detail he was after. He uses equipment that is no longer manufactured, since current day medical x-ray equipment doesn’t produce x-rays suitable for this kind of work. Combined with his artful eye, the results are extraordinary and reveal an amazing world of delicacy and beauty. I was very impressed by Dr. Raikes’ artwork when he first showed it to me, and I wanted to create an educational exhibit that Sunflower with seeds would display his magnificent floral radiography. Through a collaboration with University of Massachusetts physics professor Robert B. Hallock, we were able to produce an exhibit that not only showcases Dr. Raikes’ art but also explains the science behind the images. Visitors have the opportunity to learn about the way light works, how the eye sees, what x-rays are, and how x-ray technology can be used to create beyond the surface of objects and enable botanical art. -

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011)

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Borou Block Lot Address Parcel Name gh 1 2 1 4 SOUTH STREET SI FERRY TERMINAL 1 2 2 10 SOUTH STREET BATTERY MARITIME BLDG 1 2 3 MARGINAL STREET MTA SUBSTATION 1 2 23 1 PIER 6 PIER 6 1 3 1 10 BATTERY PARK BATTERY PARK 1 3 2 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 3 3 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 6 1 24 SOUTH STREET VIETNAM VETERANS PLAZA 1 10 14 33 WHITEHALL STREET 1 12 28 WHITEHALL STREET BOWLING GREEN PARK 1 16 1 22 BATTERY PLACE PIER A / MARINE UNIT #1 1 16 3 401 SOUTH END AVENUE BATTERY PARK CITY STREETS 1 16 12 MARGINAL STREET BATTERY PARK CITY Page 1 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Agency Current Uses Number Structures DOT;DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;NO 2 USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;LONG-TERM 1 AGREEMENT;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS NO USE-NON RES STRC;TRANSIT 1 SUBSTATION DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- 1 DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;FINAL COMMITMNT-DISP PARKS PARK 6 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 0 SANIT OFFICE 1 PARKS PARK 0 DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;IN USE- 1 TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DOT PARK;ROAD/HIGHWAY 10 PARKS IN USE-TENANTED;SHORT-TERM 0 Page 2 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Land Use Category Postcode Police Prct